Stand Up and Be Counted: Native Americans in the Federal Census

By Rose Buchanan | National Archives News

WASHINGTON, April 21, 2022 — As a reference archivist and Subject Matter Expert for Native American Related Records at the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, DC, where we house historical records of the U.S. Census Bureau and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) headquarters, I’ve often worked with researchers interested in tracing Native American ancestry using federal decennial census records. These records can provide important information about Native American ancestors when they are enumerated as such.

It’s important to note from the outset that I’m using the word census here to refer to the census of the population that the federal government takes every 10 years in the United States. The BIA has historically taken censuses of Native American tribes within its jurisdiction as well. These records were the result of legislation, removals, and other activities, and they can also be important sources for genealogy research; NARA’s BIA Rolls page provides more information about them. But in light of the 1950 Census release on April 1, I’m focusing on federal decennial census records only in this post.

As Archivist and Subject Matter Expert for Native American Related Records Cody White explains in “The Story of the 1950 Census P8 Indian Reservation Schedule,” the federal government initially excluded “Indians not taxed” from enumeration in the decennial census of the population and did not attempt to enumerate all Native people until 1890.[1] Even after 1890, instructions for enumerating Native people often changed, which sometimes led to inconsistencies in how the same person was enumerated over time. However, as the following examples will show, Native people do appear even in early censuses, demonstrating their presence and persistence in this country.

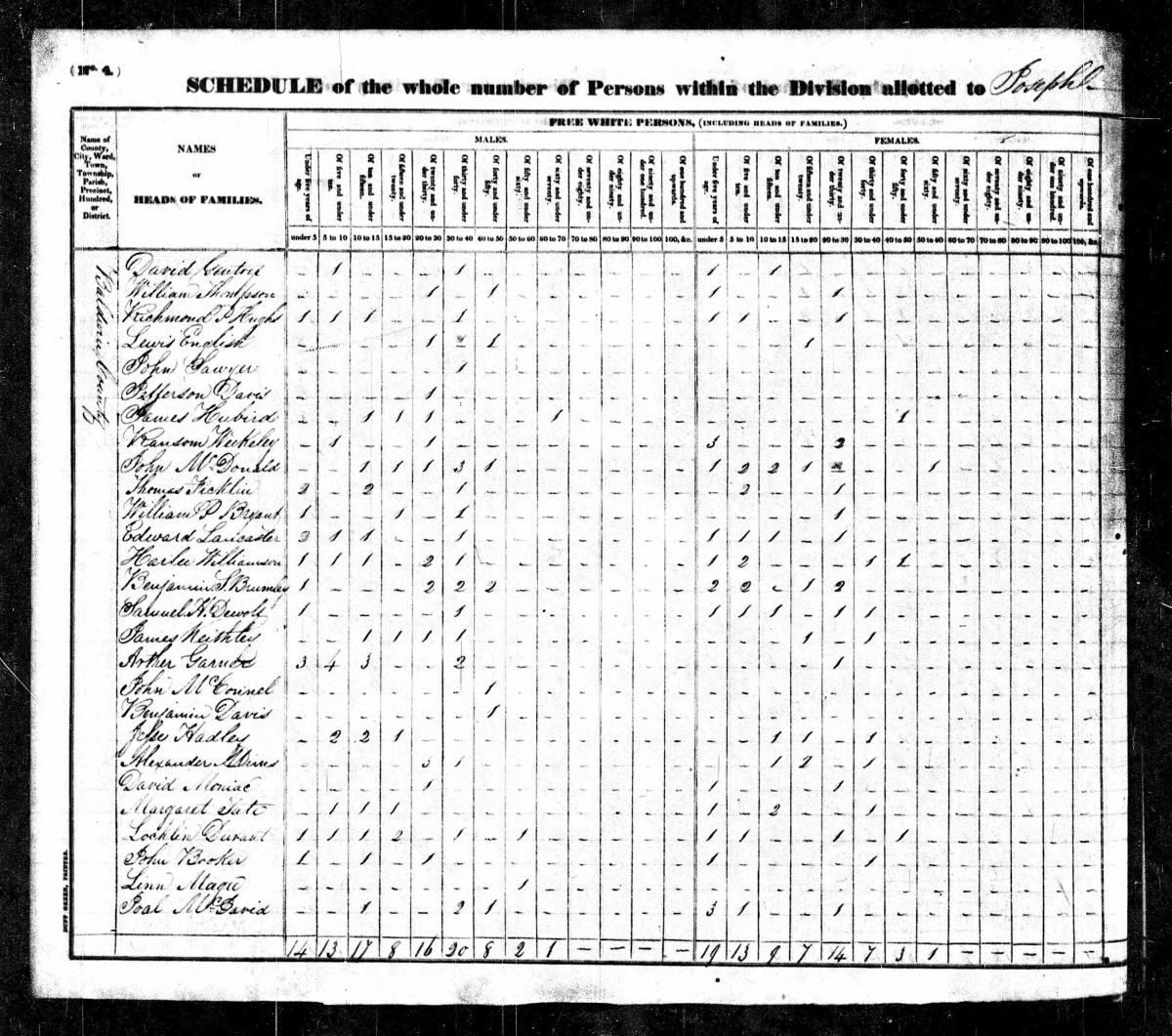

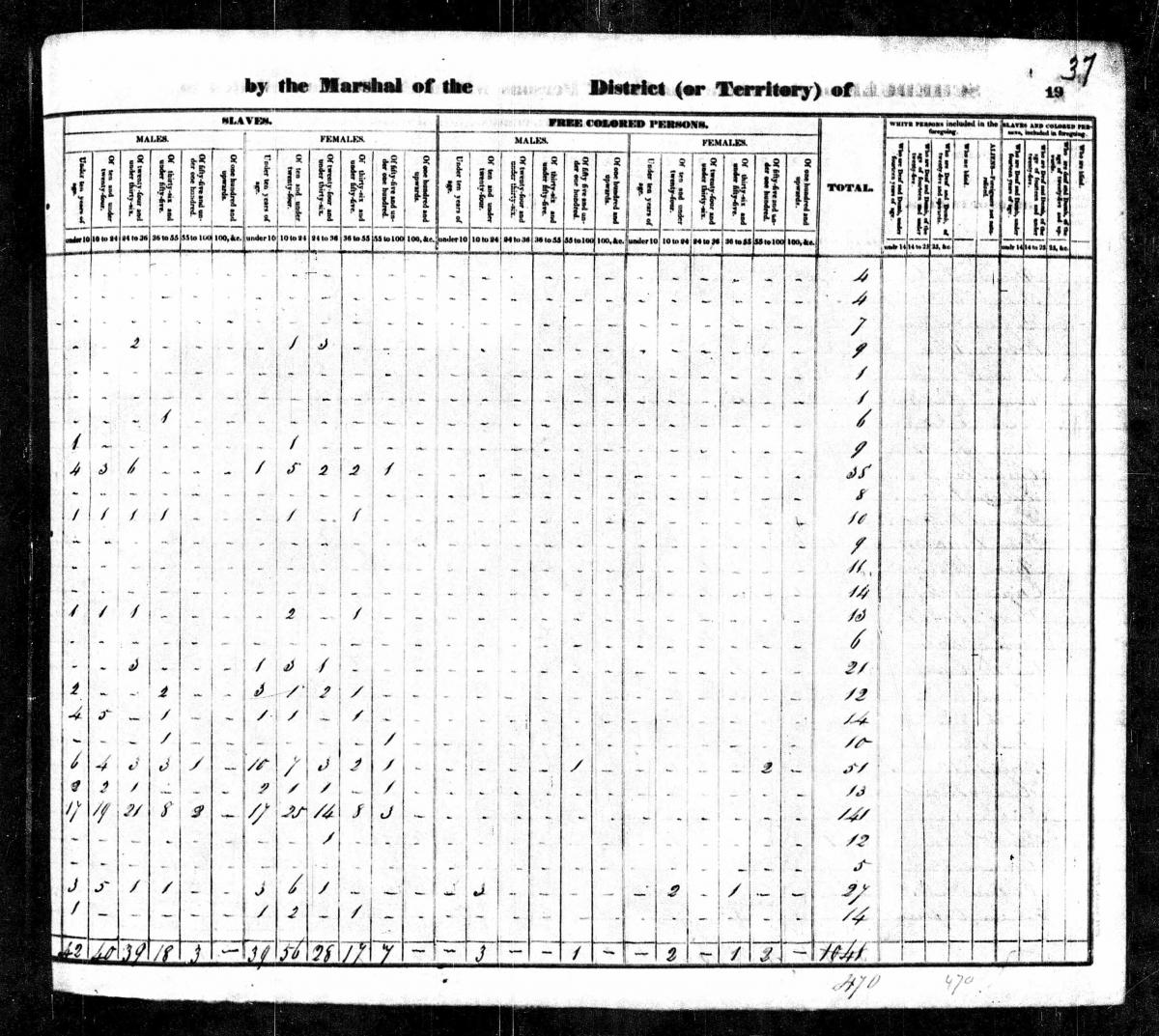

Most Native Americans are not enumerated in the 1790–1840 censuses. However, some prominent individuals living among the general population are included, and their records can be identified when their name, approximate age, and residence is known. Most are male heads of household, as census schedules prior to 1850 only distinguished between free white people, free people of color, and enslaved people, and only listed heads of household by name.

For example, David Moniac (Creek), the first Native American to attend the United States Military Academy at West Point, appears in the 1830 Census for Baldwin County, AL. He is listed as the head of household, which also included two other free people and 10 enslaved people.[2]

1830 Census record for David Moniac and household, Baldwin County, AL (see line 22) |

|

|

|

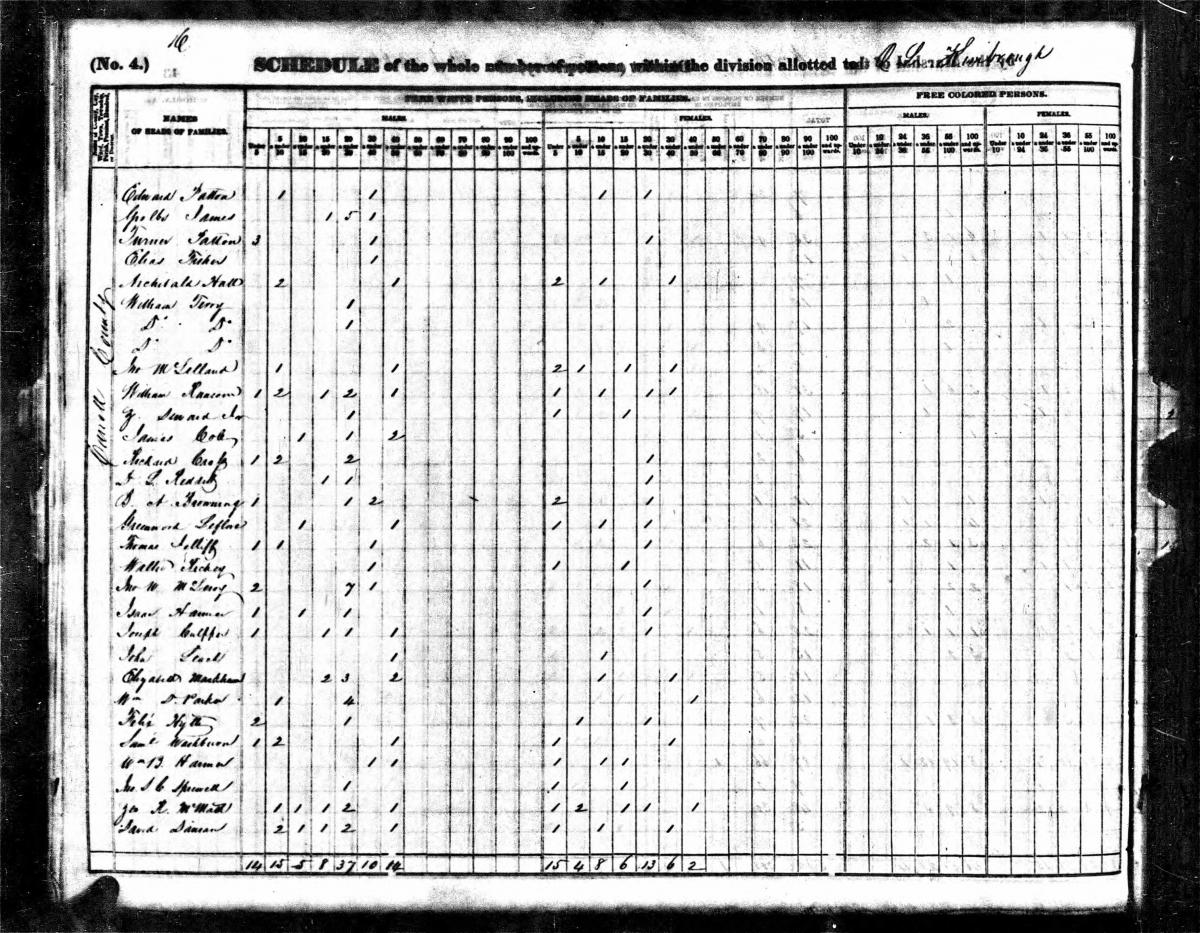

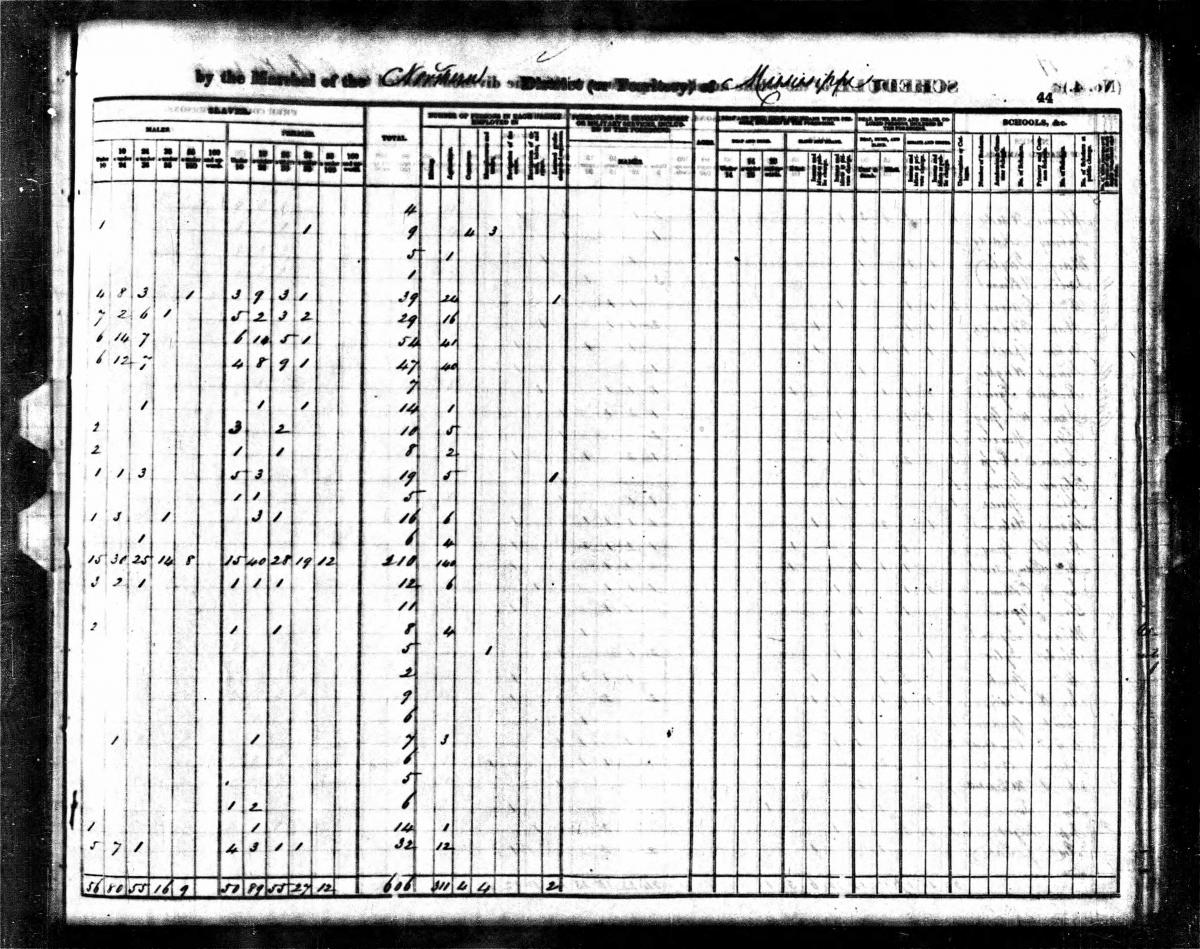

Another example comes from the 1840 Census. Greenwood LeFlore (Choctaw), a signatory to the 1830 Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek that ceded Choctaw lands in Mississippi to the U.S. government and a future Mississippi state legislator,[3] appears in the 1840 Census schedules for Carroll County, MS, along with four other free people and one enslaved person.

1840 Census record for Greenwood LeFlore and household, Carroll County, MS (see line 16) |

|

|

|

Both Moniac and LeFlore are enumerated as free white men. This may have been because both had European as well as Native ancestry (Moniac had Scottish ancestry, while LeFlore had French-Canadian ancestry), and both had settled among the general population and adopted aspects of a Euro-American lifestyle, such as attending Euro-American schools and relying on enslaved laborers to cultivate plantations.[4] To the federal government, and to census enumerators specifically, this may have signaled that both had assimilated into white society, regardless of any ongoing ties the two may have had with their tribes. In such cases, additional sources beyond the census are needed to confirm Moniac’s and LeFlore’s Native ancestry and tribal affiliations.

1850–1890

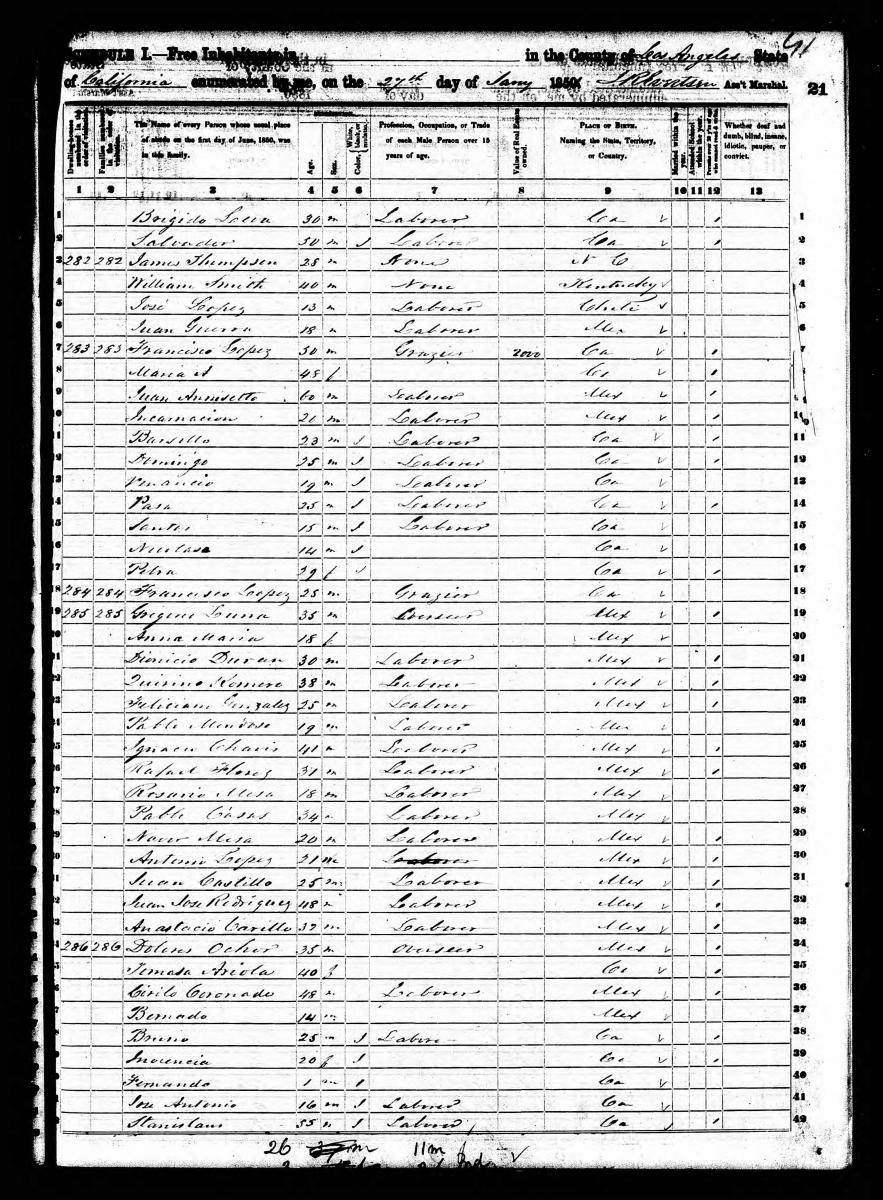

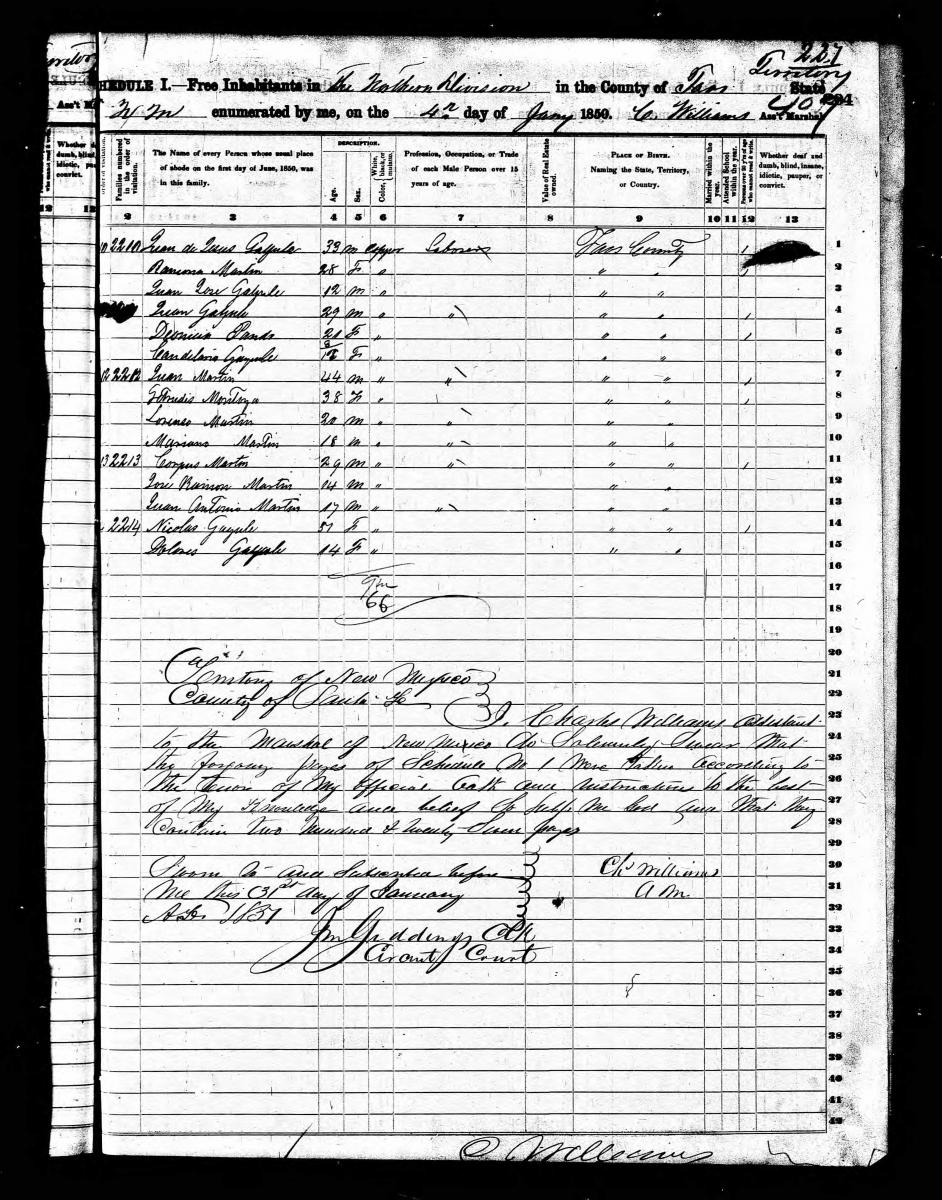

The 1850 Census continued to exclude most Native people, but the population schedule that year included a new column for “Color.” Although enumerators were instructed to list people as white, black, or mulatto, some went off script and identified Natives in the general population using a different abbreviation or term. For example, in Los Angeles, CA, enumerators used “I” for “Indian.” In New Mexico Territory, enumerators identified residents of Taos Pueblo as “copper.”

1850 Census schedule from Los Angeles, CA. Native Americans are enumerated as “I” in the “Color” column. |

1850 Census schedule from Taos Pueblo, New Mexico Territory. Native Americans are enumerated as “copper.” |

|

|

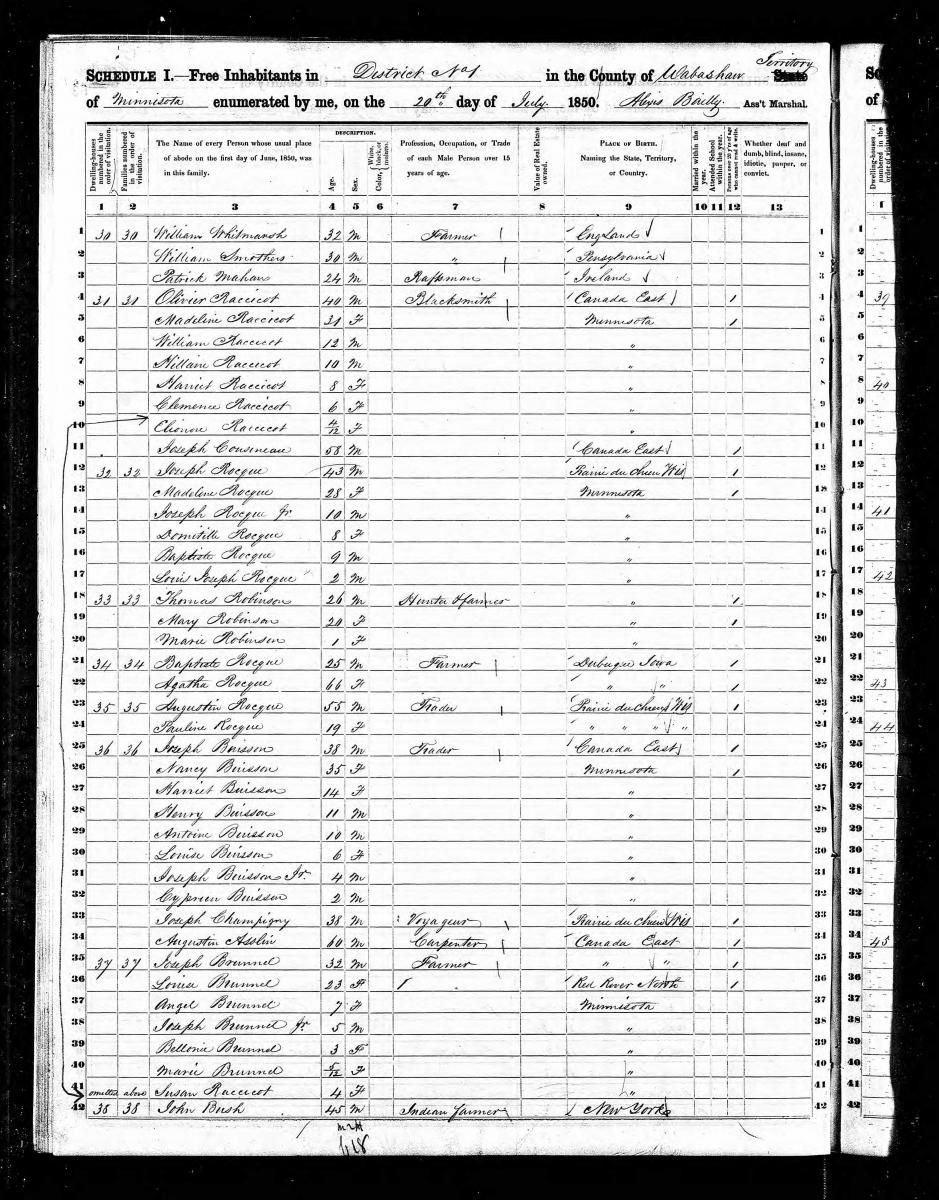

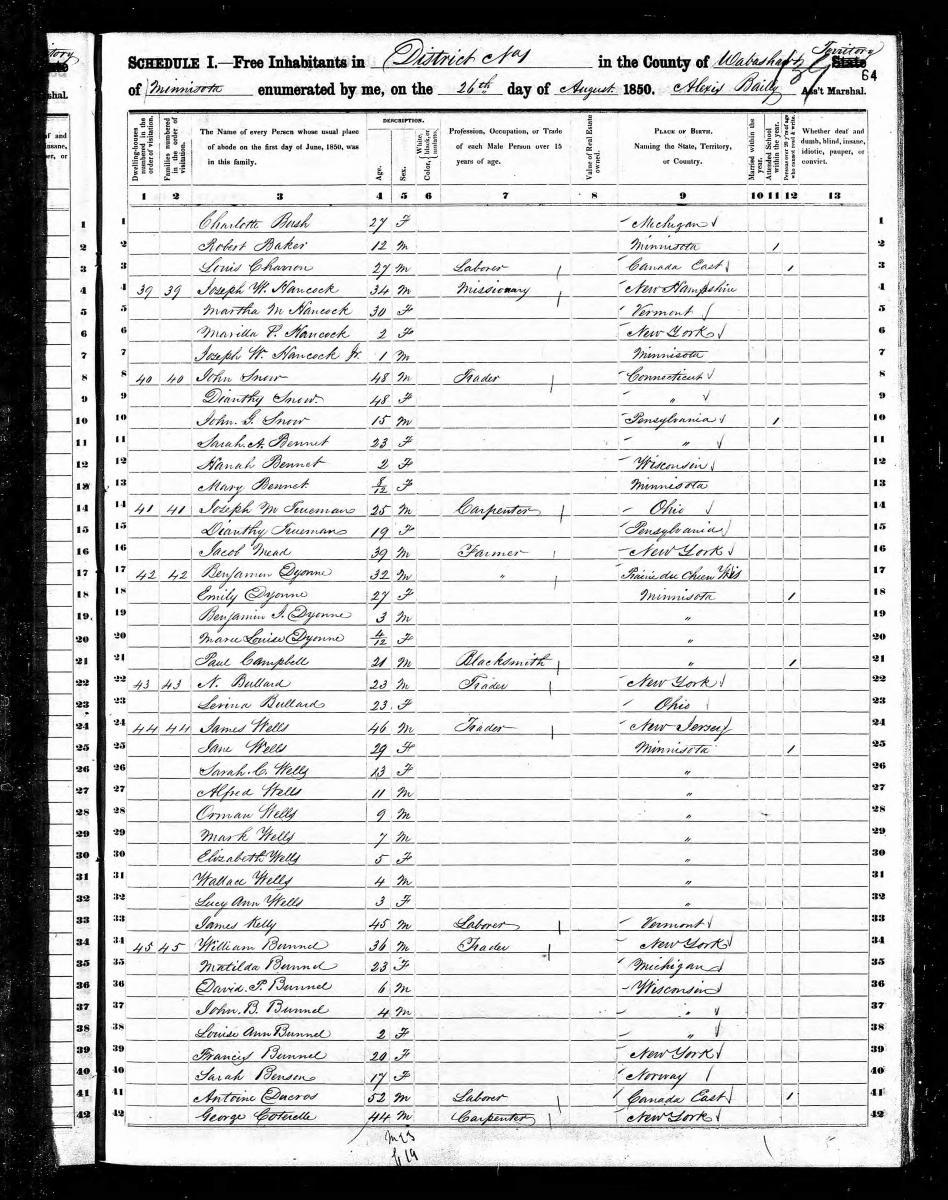

In Wabasha County, Minnesota Territory, an enumerator even listed John Bush as an “Indian farmer” under the heading for “Profession, Occupation, or Trade,” in contrast to Bush’s farming neighbors, whom the enumerator only listed as “farmer.”

1850 Census record for John Bush and household, Wabasha County, Minnesota Territory (see line 42 of the page at left and lines 1–3 of the page at right) |

|

|

|

More research is needed to confirm each person’s Native ancestry in these instances, but the census records provide some clues for getting started.

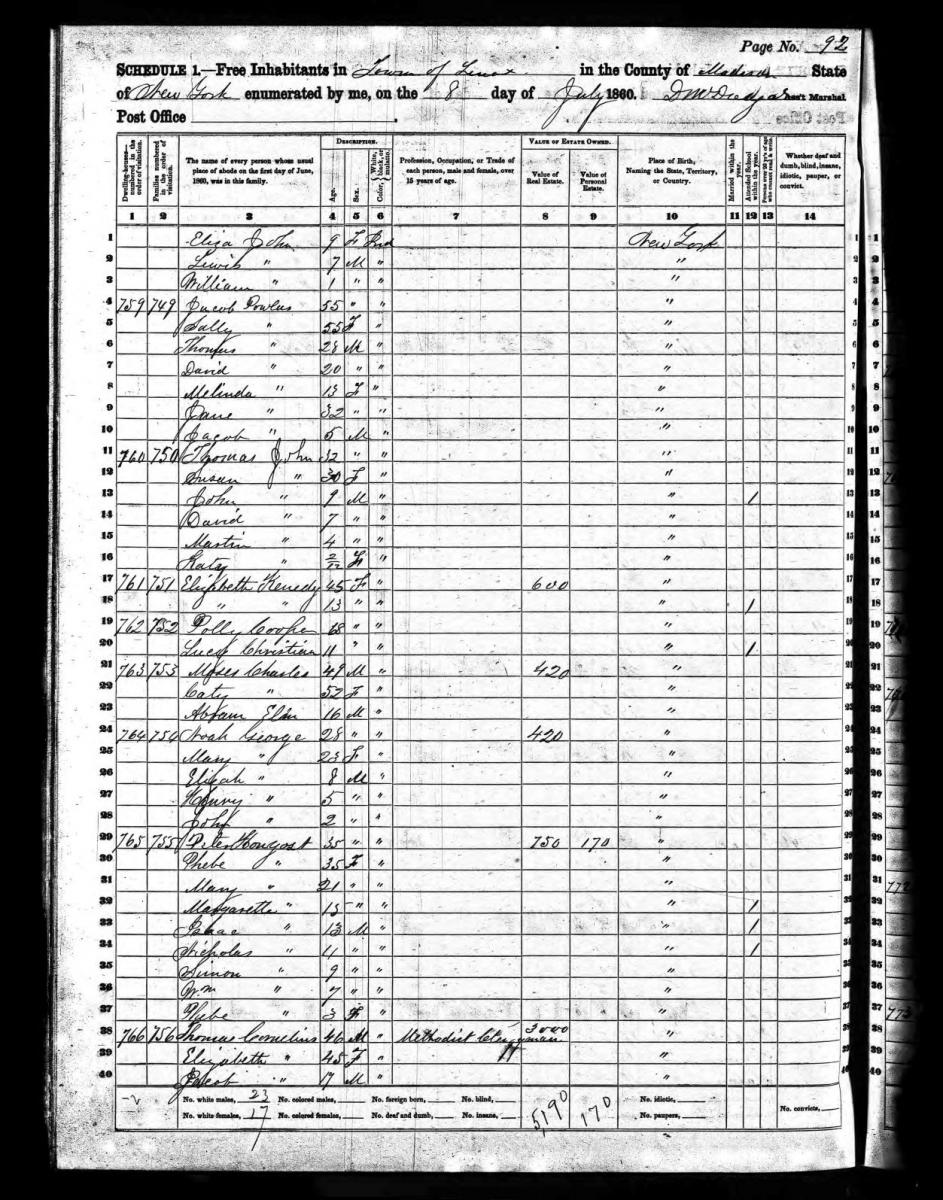

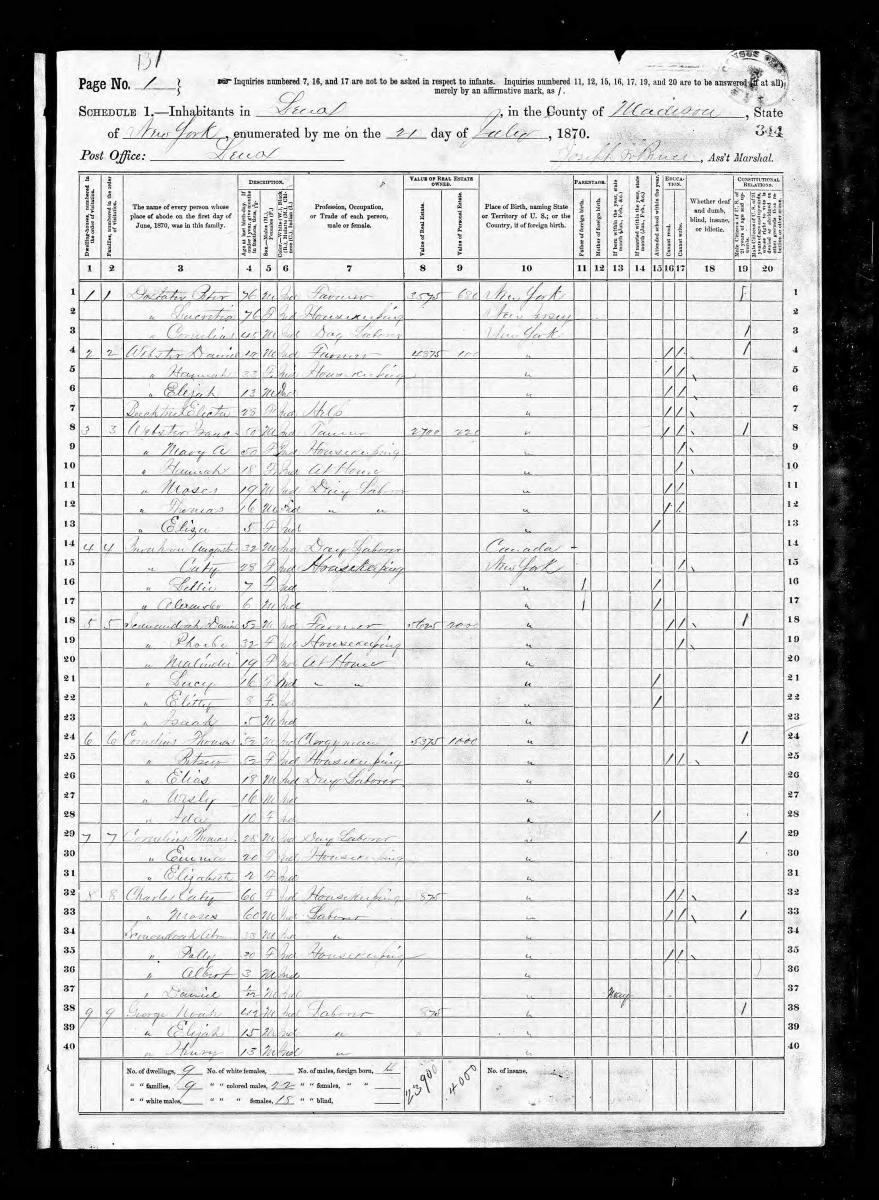

The 1860 Census was the first to include specific instructions about enumerating Native Americans: those “who have renounced tribal rule, and who under State or Territorial laws exercise the rights of citizens,” were to be listed as “Indian” in the column for “Color.” Similar instructions were given for the 1870 Census. Due to these changes, over 44,000 American Indians were enumerated in the 1860 Census and over 25,000 in the 1870 Census.

Reverend Thomas Cornelius (Oneida) was one such person. Cornelius was born on the Oneida Reservation in New York in the early 1800s. He converted to Christianity in the 1820s and thereafter became a prominent Methodist preacher among the Oneida.[5] In both the 1860 and the 1870 censuses, Cornelius and household members are enumerated in Lenox, Madison County, NY, and are identified as Indian.

At left: 1860 Census record for Thomas Cornelius and household, Lenox, Madison County, NY (see lines 38–40) |

At right: 1870 Census record for Thomas Cornelius and household, Lenox, Madison County, NY (see lines 24–28) |

|

|

Based on the instructions to enumerators alone, Cornelius’s enumeration in these censuses would suggest that he had “renounced tribal rule” and assimilated into the general population. However, in 1874—just four years after the 1870 Census—Cornelius and other Oneida leaders sent a memorial to Congress outlining the money that the federal government owed the Oneida according to treaty provisions. The memorial demonstrates that Cornelius was actively involved in advocating for his community and that he had not “renounced” ties to them, even if he may have adopted some aspects of Euro-American culture, like Christianity.

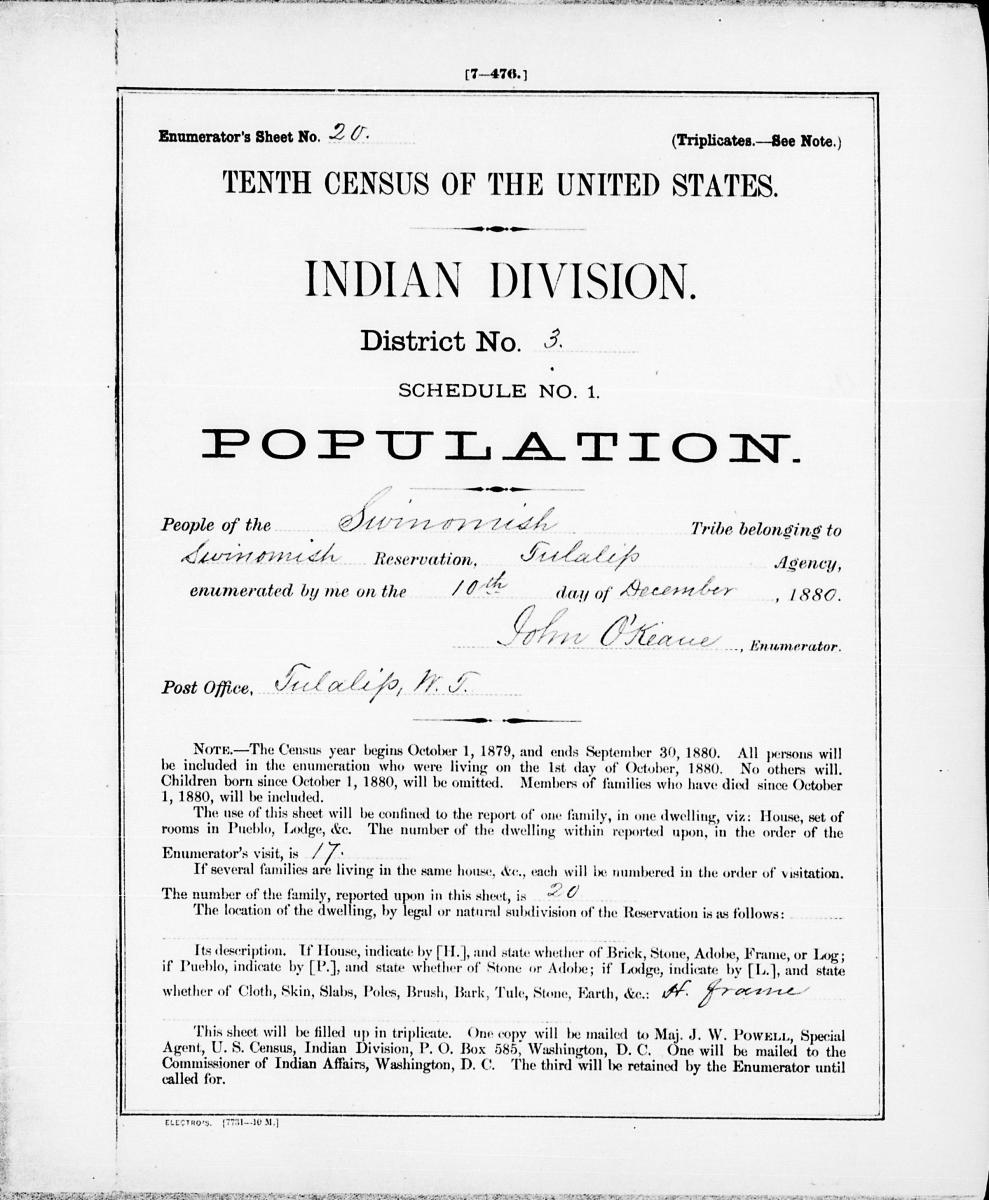

The instructions for the 1880 Census were more expansive than those for previous censuses. They specified that Native Americans, including those with non-Native ancestry, should be enumerated when “found mingled with the white population, residing in white families, engaged as servants or laborers, or living in huts or wigwams on the outskirts of towns or settlements.” The congressional act authorizing the 1880 Census (20 Stat. 475) also permitted the Superintendent of the Census to gather data about “Indians not taxed” within the jurisdiction of the United States on special Indian schedules. Census officials ultimately enumerated Natives living on select reservations in Washington Territory, Dakota Territory, California, and elsewhere.[6]

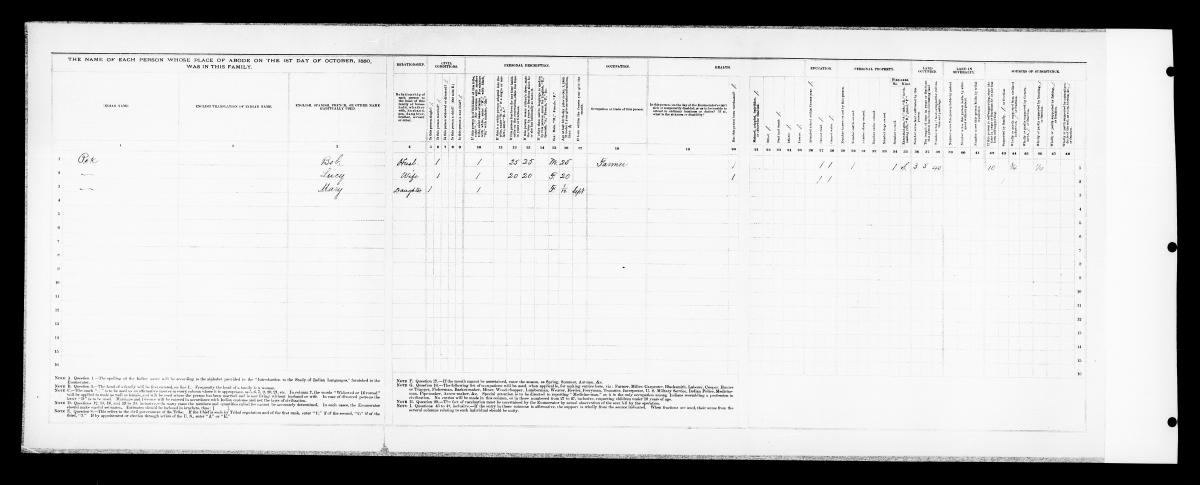

This included Pok (Bob), his wife Lucy, and their newborn daughter Mary, who are listed in the 1880 Special Census of Indians schedules for the Swinomish Reservation in Washington Territory. The schedule indicates that Pok was a 25-year-old farmer and that he and 20-year-old Lucy had lived on the Swinomish Reservation their entire lives. Their daughter Mary was born in September 1880, one month before the official start of enumeration on October 1, but she would have been three or four months old when census enumerator John O’Keane visited the reservation in December 1880.

The 1880 Census also reported estimates of the Alaska Native population, although individual schedules for Alaska did not survive.[7]

The 1890 Census was the first to seek to count all Native Americans in the continental United States, regardless of whether they lived on a reservation or in the general population. Most schedules from this census were destroyed in a 1921 fire in the Department of Commerce building, but not before aggregate population data was published. [8]

For a deeper dive into Native enumeration in the 1860–1890 censuses, see the 2006 Prologue article “Native Americans in the Census, 1860–1890.”

1900–1940

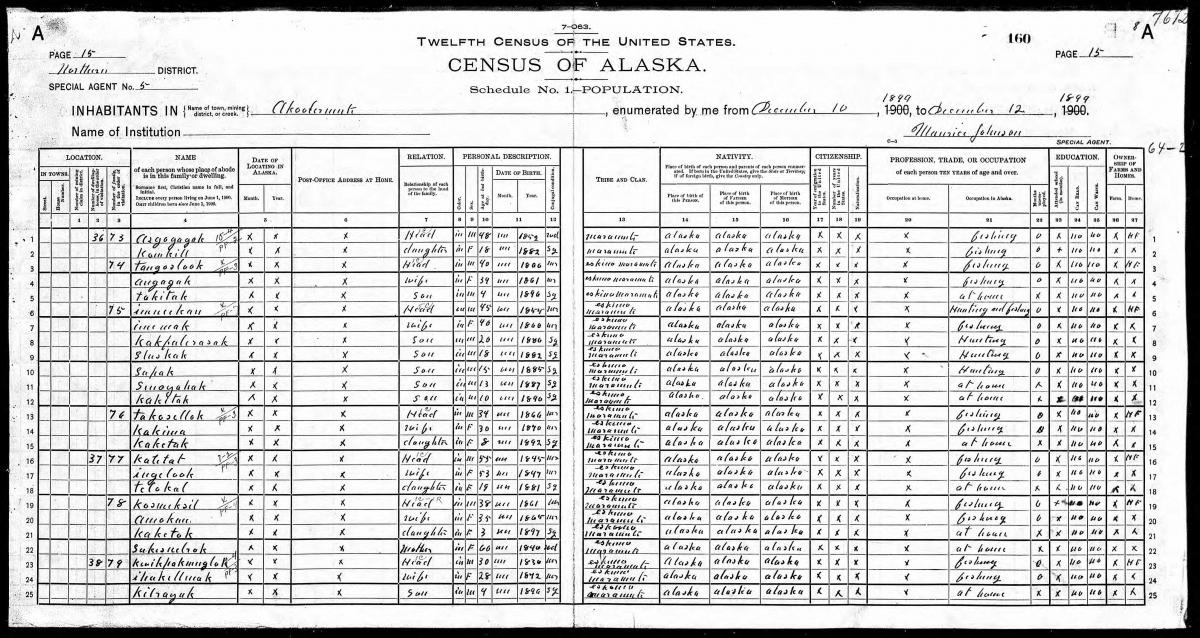

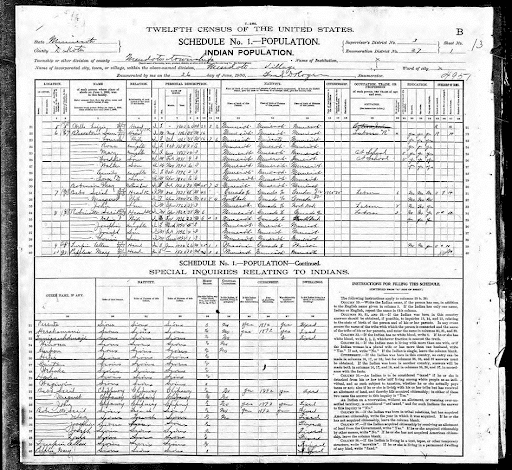

The 1900–1940 censuses also attempted to count all Natives living on reservations and in the general population. The 1900 Census introduced a special Indian schedule for Natives living on reservations or in family groups outside of reservations, which asked for the person’s tribe and their parents’ tribes, among other information. Alaska was enumerated using a single schedule, which incorporated a question about each person’s tribe and clan, if relevant.

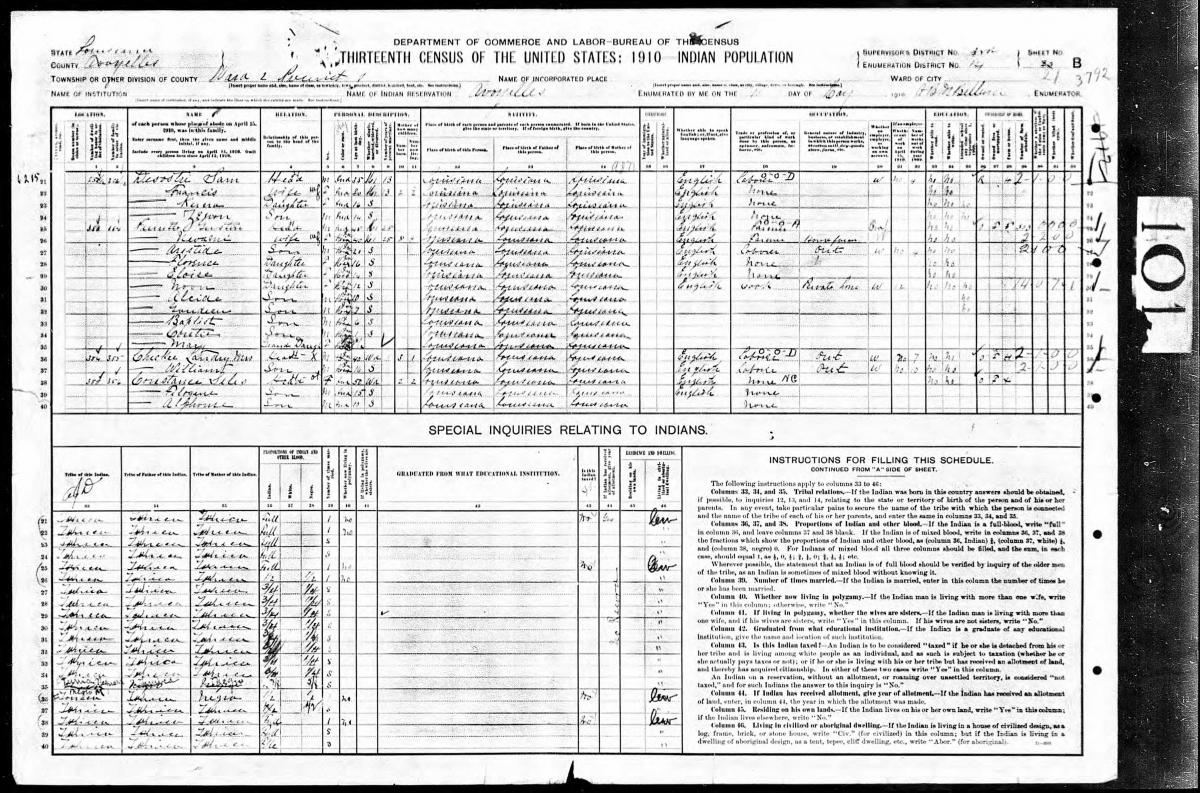

The 1910 Census also included a special Indian schedule, which asked more detailed questions about Native people’s non-Native ancestry. For example, the special Indian schedule returned for Marksville, Avoyelles County, LA, lists members of the Tunica Tribe, some of whom had Black ancestry.

The 1920 Census did not include a special Indian schedule; the instructions for enumerators only offered “Indian” as an option for the “Color or race” question, without further comment.

The 1930 and 1940 censuses included similar questions about race but provided census takers with more detailed instructions for enumerating Natives: enumerators were to report individuals as Indian according to their degree of “Indian blood” and whether they were “regarded as an Indian in the community.” Additionally, for the 1930 Census, enumerators were to record an individual’s tribe in the column for their mother’s place of birth.

However, as with prior censuses, enumerators for the 1900–1940 censuses sometimes interpreted the instructions about race and tribal affiliation differently. For example, in the 1900 Census, Cyril Robinette and his family appear on the special Indian schedules for Mendota, Minnesota, as “Sioux” only. In 1910, they again appear on the special Indian schedule, although their entry is more detailed: Cyril is listed as “Wahkepute Sioux” and “white,” while his wife Delia is listed as “Chippewa” and “white.” Their children—Josephine, Joseph, and Louis at the time—are listed as “Wahkepute Sioux,” “Chippewa,” and “white.”

In the 1920 Census, each family member is listed as white; no reference is made to their tribal affiliation. In the 1930 Census, most family members are again listed as Indian: Cyril is listed as “mixed-blood Chippewa,” while his children are listed as “mixed-blood Sioux.” However, Delia is listed as white only, with no reference to her tribal affiliation (only a reference to her father’s French-Canadian ancestry). By the 1940 Census, all family members are again listed as white, with no reference to their tribal affiliation.

These inconsistencies point to the challenges of using federal population census records to document a person’s specific tribal affiliation, even when the census identifies the person as Native American. Other sources, like BIA census rolls, can be useful to consult in these instances.

Conclusion

Hopefully these examples show the potential of federal census records for tracing Native American ancestry. While the records have their limitations, especially when it comes to documenting tribal affiliations, they are some of the most easily accessible and searchable records we have for tracing Native people’s presence and persistence in a particular area.

Special thanks to Cody White, Archivist and Subject Matter Expert for Native American Related Records.

[1] Article 1, Section 2, of the Constitution excluded “Indians not taxed” from counting toward a state’s population when determining the number of seats that each state should have in the U.S. House of Representatives. Although the Constitution did not define this phrase, census officials typically interpreted it to mean Native Americans “maintaining their tribal relations and living upon Government reservations.” See U.S. Census Bureau, A Compendium of the Ninth Census (June 1, 1870), page 19.

[2] See the Department of Veterans Affairs’ blog post “Veterans Legacy Program: Major David Moniac, first Native American West Point graduate and leader of the Creek Volunteers” (2018).

[3] See James P. Pate, “LeFlore, Greenwood (1800–1865) ,” Oklahoma Historical Society.

[4] See Heriberto Dixon and Lawrence M. Hauptman, “From West Point To Wahoo Swamp: The Career of Cadet David Moniac, Class of 1822 ,” American Indian Magazine 17, no. 1 (Spring 2016); James Taylor Carson, “Greenwood LeFlore ,” Mississippi Encyclopedia, Center for Study of Southern Culture (updated April 14, 2018).

[5] See Cornelius’s obituary, available online through the Oneida Nation’s website .

[6] See U.S. Census Bureau, “Censuses of American Indians.”

[7] See U.S. Census Bureau, “1880 Census: Volume 1. Statistics of the Population of the United States. Statistics of the Population of Alaska.”

[8] See U.S. Census Bureau, “Report on Indians Taxed and Not Taxed in the United States (Except Alaska) at the Eleventh Census: 1890.”

PDF files require the free Adobe Reader.

More information on Adobe Acrobat PDF files is available on our Accessibility page.