Records Help Family Connect With Oneida Nation Activist's Legacy

Mary Cornelius Winder's Descendants Examined Letters at National Archives at New York City

By Michael Davis | National Archives News

WASHINGTON, January 8, 2024 – Original copies of handwritten letters to federal government officials by Oneida Nation activist Mary Cornelius Winder helped connect some of her descendants with her legacy during a visit to the National Archives at New York City this past summer.

The visit came about after the National Archives at New York City received a research request from the Syracuse Stage’s Backstory program, which is producing a play centered on Winder called Our Words Are Seeds, written by Ty Defoe. Backstory is an educational theater program that tells historical figures’ stories for middle and high school students.

Kate Laissle, the theater’s director of education, first came to view the collection on July 14, 2023. She returned for a second visit with the theater’s director of community engagement Joann Yarrow and seven members of the Winder family from central New York, on July 31.

“Holding her letters in my hands made me feel so close to her,” said Michelle Schenandoah, great-granddaughter of Mary Cornelius Winder. “If I had only known that her letters were close by all those years.”

Michelle Schenandoah had spent several years searching for information about the legal history of her people’s land claims when she attended New York Law School, only a few blocks away from the National Archives at New York City.

Mary Cornelius Winder (1898–1954) was an activist for the Oneida Nation, one of the founding First Nations of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy. From 1920 until she died in 1954, she conducted a campaign of writing letters to federal government officials regarding Oneida land claims, petitioning the government to give the Oneidas back their land.

The letters demanded compliance with the 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua, which called for the return of all the land illegally seized from the Oneida Nation. Instead of honoring the treaty, in 1919 the U.S. Government acknowledged only 32 acres in what are now Madison and Oneida counties in New York, where a handful of Oneida families remained in their homelands.

Due to these illegal land takings, in the early 1800s, most Oneidas relocated to Wisconsin and Canada, and a few families moved nearby to live among the Onondaga Nation, including Mary’s family

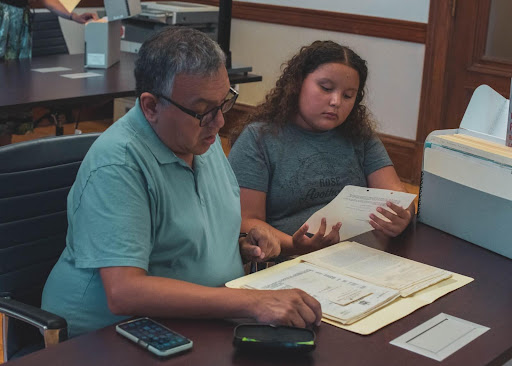

Winder family descendants viewed some of the original letters sent by Winder to federal officials, which are contained within Bureau of Indian Affairs administrative files. A related correspondence series contains additional materials related to Mary Winder and other family members. Work to scan and upload these materials into the National Archives Catalog is in process.

In 1948, Mary Winder wrote to Bureau of Indian Affairs officials:

I am writing in behalf of the Oneida Indians of N.Y.S living on the Onondaga Indian Reservation. . . . Just why we do not get any satisfaction from the Indian Department is more then I can see, for my sister and I have been to your office twice with no satisfaction at all, we have lands that N.Y.S. never paid for, and it seems that the Indian department should look into this for us. Either the New York state pay our people or give back our lands then we can have our own reservation too. I think the Oneida people deserve attention from your office.

The family members who viewed Mary Winder’s letters spanned multiple generations. The eldest descendants present were granddaughters Wanda Wood and Mary Winder, who both lived with Winder as children and recounted many memories during the visit. The other five descendants were granddaughters Diane Schenandoah and Shirlee Winder, great-grandchildren Michelle Schenandoah and Shane Hill, and great-great-granddaughter Sequoia Shenandoah (Onondaga).

“At the end of their time with the records, they invited staff to join hands as they offered words of remembrance and a song led by Diane Schenandoah, a traditional Faithkeeper of the Oneida Nation Wolf Clan,” said Chris Gushman, Director of Archival Operations in New York. Diane’s daughter Michelle brought a set of replica wampum belts that commemorate treaties made with the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, to which the Oneida Nation belongs.

Gushman said that while the New York City staff were accustomed to seeing how genealogy researchers react when making personal connections with the records, the visit with Winder’s descendants was on a different scale.

“We knew we had these records and kind of understood what they were, but it wasn’t really until the family got here and we got the whole story from them and saw them experience the research, that we understood what we have in our collections and their importance to not only family, but the community,” he said.

“Many of Mary’s descendants over the generations have been influenced by her work and carried on her legacy to reclaim Oneida lands,” said Michelle Schenandoah. “Most inspired by this visit to the National Archives was her great-great-granddaughter Sequoia, who said she wants to become a lawyer to work for our Haudenosaunee people.”

Mary Cornelius Winder died three years after the Oneida land claim was officially filed. Today, the Oneida Nation has regained more than 18,000 acres of their original homelands—the most they have had recognized sovereignty over since 1824.

“This visit really drove home the importance of the National Archives and how the work we do to preserve and provide access to our holdings can make an impact,” said Gushman.

Winder’s letters and work are also featured with other Indigenous leaders in an exhibit, Native New York , in the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian–New York branch , located in the same building as the National Archives at New York City.