National Archives Records Inform Fellowship Research on History of Surveillance

By Angela Tudico | National Archives News

WASHINGTON, August 19, 2024 — Dr. Ashley D. Farmer utilized her time as a 2023 National Archives Foundation Cokie Roberts Women’s History Fellow to research her third book, which will examine how the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) surveilled Black women activists throughout the 20th century.

This research for the forthcoming academic work, Gendering Surveillance: African American Women Activists and the FBI, represents a pivot for Farmer, who typically studies history from the bottom up—from the perspective of the Black women activists themselves. For this “top-down” history, the National Archives at College Park’s FBI holdings proved critical to tracing when and how the FBI surveilled Black women.

“If you want to know what the FBI is thinking, feeling, who they were tracking; the National Archives is the number-one place to go,” Farmer said. “Not only do they have the Department of Justice records, under which the FBI began as the Bureau of Investigation in 1908, they also have most of the FBI’s administrative records from the 20th century. It really shows the start of the program.”

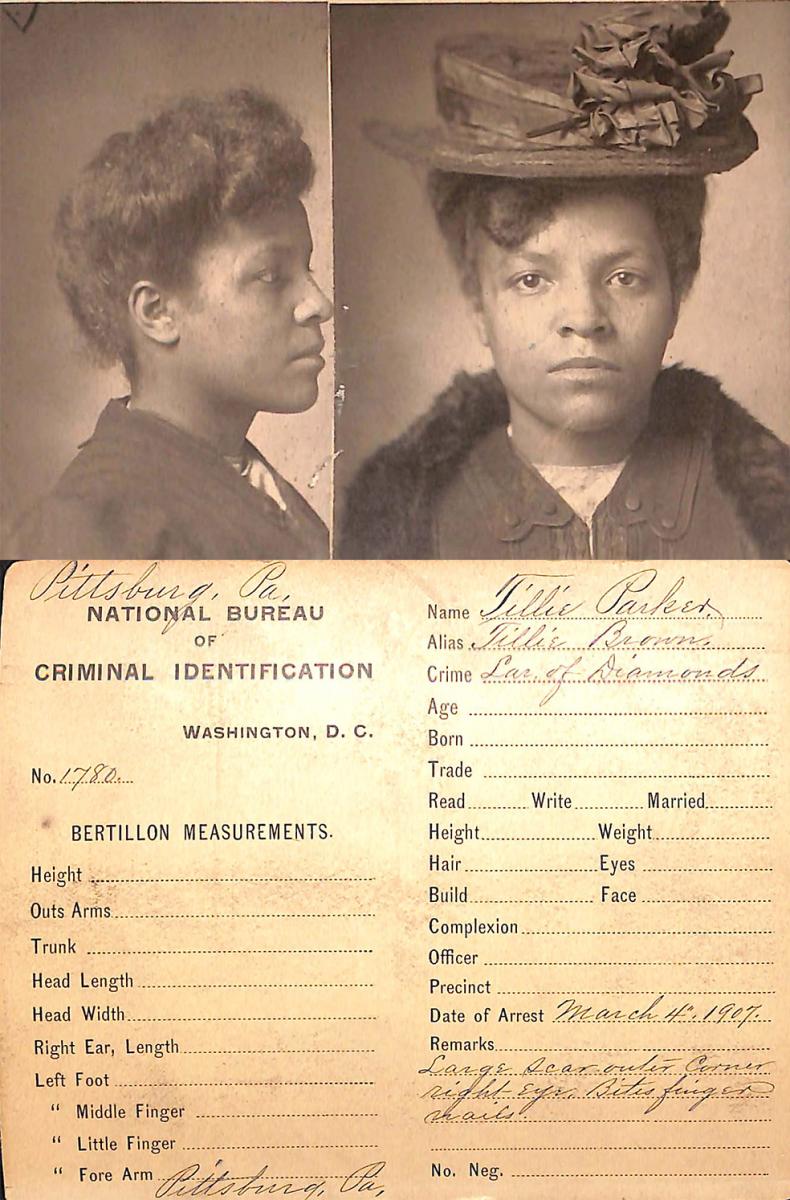

The Records of the Federal Bureau of Investigation are vast. Farmer found longtime agency head J. Edgar Hoover’s scrapbooks (over 200 boxes alone), internal case write-ups, special agent application files, and the early filing and fingerprinting systems helpful to paint a picture of the nascent FBI. Criminal Identification Cards that predated the formation of the FBI and were compiled by the International Association of Chiefs of Police also proved useful for understanding the early days of criminal surveillance.

Farmer noted only a handful of Black women from these earliest surveillance records and an absence of notable names or famous activists like those later tracked by Hoover’s Counterintelligence Program in the 1960s, such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Angela Davis. The early files focused on men, regardless of race or ethnicity, and White women. When Black women begin to appear in the FBI files, it is for petty crimes like theft.

“What is really interesting about this early era of surveillance is the mundanity of it. Whereas you would think one would find reports about activists or political figures, instead we find reports like those of agents tracking a young Black girl riding the train from Washington, DC, to Maryland. She was a subject of surveillance because the FBI suspected she was transporting liquor across state lines during the Prohibition era,” said Farmer. “At a certain point that changes, and you see that slippage from Black girls and women being listed as a ‘subject’ to a ‘subversive’ in the files. I am still teasing out what that all means, but it was fascinating to see, and it is important to bear that out for the historical record.”

Farmer is an associate professor of African and African Diaspora Studies and History at the University of Texas at Austin. She earned her doctorate in African American Studies and her master’s degree in history from Harvard University, and her bachelor’s degree from Spelman College.

She is conducting her research as a 2023 recipient of the Cokie Roberts Women’s History Fellowship.

Supported by the National Archives Foundation (NAF), the fellowships are awarded to early to mid-career historians, journalists, authors, or graduate students who perform and publish new research to elevate women’s history using records held by the National Archives.

“It is a blessing to get to a mid-career point, but it is also tough because there are a lot of funding mechanisms rightfully geared toward early career. But if you want women to continue to be productive, it doesn’t happen without funding,” said Farmer. “I want to emphasize how special this particular fellowship is for being able to focus on women’s ability to do that because I do think it’s rare.”

The National Archives Foundation launched the fellowship in 2019 to honor noted author, journalist, and long-time Foundation board member Cokie Roberts, who spent her career shining light on the stories of many women who had an impact on U.S. history.

“My mom understood something vital about women—they often make history, but they make it in their own way,“ said Rebecca Roberts, Cokie Roberts’ daughter and NAF board member. “Their stories are often obscured by neglect, sexism, misinterpretation, or even by the women themselves. This fellowship gives historians the resources and support they need to uncover and celebrate women’s stories.”

The National Archives Foundation recently named two 2024 Cokie Roberts Women’s History Fellows, Dr. Rachel Kline and Molly Lester.

Read about previous Cokie Roberts Women’s History Fellows: Kara Dixon Vuic, Lois Leveen, Randa Tawil, Jessica Kahkoska, and Rebecca Brenner Graham.