Remembering the 1973 NPRC Fire

By Victoria Macchi | National Archives News

WASHINGTON, July 10, 2023 — Fifty years ago this week, a fire destroyed millions of military personnel documents at the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) in St. Louis, MO, part of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

The event—unprecedented in the scale of its damage to federal records—changed how the National Archives builds its facilities, maintains its holdings, and serves veterans and the public.

To honor the anniversary, the National Archives is sharing its most comprehensive effort to document the history and resources available to understand the NPRC fire, its aftermath, and the changes it led to in policies and procedures.

A new Special Topics page gathers these records and resources related to the fire, including:

- An extensive ongoing oral history project from the National Archives Historian

- Images from the St. Louis Preservation Lab of how staff work with burned records

- A one-page fact sheet

- Quick access link to requesting veterans’ records online

“We've learned so much about fire safety and recordkeeping as a result of the NPRC fire. As we recognize this anniversary, we are continuing to improve how the nation’s records are kept and made accessible for all Americans,” Shogan added.

“It's been 50 years since the NPRC fire, and the National Archives and the nation are still recovering from the ashes,” said Dr. Colleen Shogan, Archivist of the United States. “I’ve seen firsthand the extraordinary lengths our staff in St. Louis go to every day to piece back together the records our veterans and their families need. It's a sobering reminder of both how important and how fragile our mission can be.”

History

On July 12, 1973, a fire broke out in the National Personnel Records Center at 9700 Page Avenue in St. Louis, MO. It destroyed approximately 16–18 million Official Military Personnel Files (OMPFs).

At the time, the General Services Administration—then the National Archives’ parent organization—owned the building.

In the scramble to put out the fire, first responders doused the building. The main fire took four days to control. Hotspots lasted about a month.

The veterans’ records most affected were of U.S. Army, Army Air Force, and Air Force personnel.

The fire destroyed more than three-quarters of these documents. These records are critical to support veterans seeking benefits, like health care, home loans, and military funerals.

Staff came together swiftly to identify and preserve alternate sources.

“Because of the actions taken immediately after the fire, especially with regard to identifying, collecting, and indexing other record series that could be used to verify service, we are normally able to reconstruct basic service and issue a document which can be used in lieu of a separation document (DD Form 214) to secure benefits,” said NPRC Director Scott Levins. “In fact, to date our Records Reconstruction technicians have been successful in reconstructing details of service despite the loss of the personnel file 5.5 million times to support our nation’s veterans.”

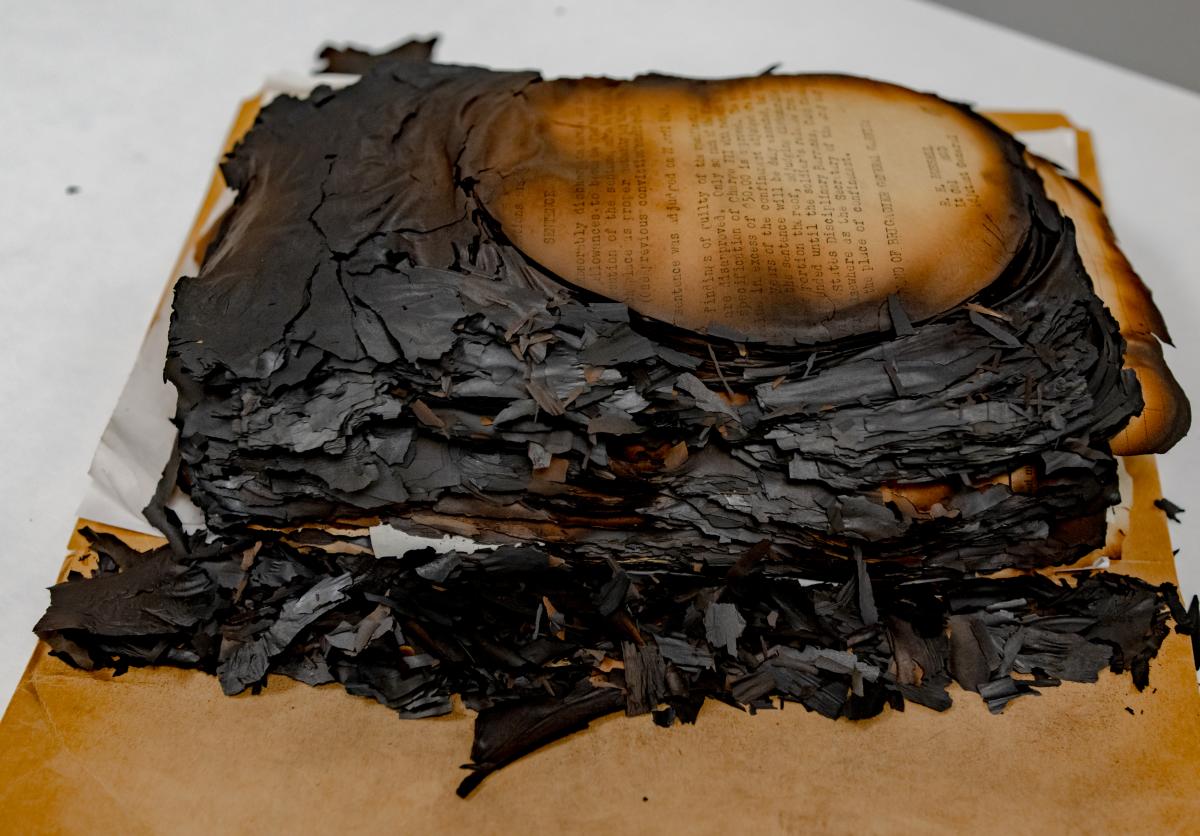

Staff salvaged as much as possible from the debris at the Page Avenue building. But the combination of flames, water, and ensuing mold damaged many records that survived the blaze.

Aftermath

To this day, staff in St. Louis work with the surviving records—known as the B-files—to ensure that veterans, their families, and other researchers can access the information they need—sometimes urgently.

The Preservation and Conservation Branch in St. Louis triages more than 30,000 fire-affected records annually. Those deemed high priority, like for health care or funeral benefits, are completed in less than three days on average.

“We sometimes are working from crumbling bricks of scorched paper,” said Vicki Lee, Preservation Officer in the St. Louis Preservation and Conservation Branch. “We have honed the best techniques for ensuring these records don’t degrade further by housing them in cool storage, then we carefully assess our next steps when we get a request. We go to huge lengths to support these veterans and their families.”

When the damage is too extensive to read or scan with an infrared camera or the record is gone entirely, Archival staff research auxiliary and organizational records like morning reports and unit rosters to help reconstruct details of the veteran’s record of service.

“There are a number of auxiliary records collected after the fire from the military branches of service, state and local governments, as well as other federal agencies that can be used to reconstruct a service member’s record,” said Theresa Fitzgerald, Director of the National Archives at St. Louis. “Since the agency established a Research Services section in St. Louis, we have been able to take in these other record collections. For example, we have general court-martial records, Selective Service records, World War I burial files, individual deceased personnel files … these go a long way to supplement what was lost back then.”

If the preservation team and archivists’ efforts are unsuccessful, staff reach out to state and federal agencies to search for additional sources of the information.

Changes

In 1999, the National Archives established a Preservation Program at NPRC to work with the 6.5 million records saved from the fire. In 2004, the fire-affected records became part of the National Archives’ permanent holdings.

A new facility completed in 2011 was built for long-term records storage with climate-controlled storage bays and a robust fire-suppression system.

“Fires, flooding, hurricanes, earthquakes—these are the things that keep me up at night. And these have all impacted NARA as well as other federal departments and agencies in the recent past,” said William Bosanko, Chief Operating Officer.

The fire in St. Louis drove changes in requirements in the fire code and in regulations, Bosanko added.

Developments within the agency also include improvements for storage design to withstand the spread of fire, detecting and extinguishing the earliest signs of smoke through sensors and sprinkler systems, and keeping records in smaller storage areas to prevent massive fire spread and loss of records.

Additionally, the National Archives created stronger emergency response plans that factor in threats that could affect the building, records, and staff. Those plans are reviewed and updated annually.

The agency also invites local police, fire, and other emergency medical services into its facilities to become familiar with and understand the unique aspects of the National Archives’ work.

Digitization and the future of recordkeeping

In the early 2000s, the National Archives studied the cost to digitize every B-file. Due to the extent of the damage and the fragility of the records, that estimated cost would have surpassed the agency’s budget. Instead, digitization of the damaged records is done case by case, as requests are made.

Nevertheless, the NPRC fire accelerated interest in creating, processing, and delivering electronic records at the National Archives.

As Theodore Hull, now Director of the Electronic Records Division, noted in a 2006 piece for the National Archives magazine Prologue:

Following the fire, NPRC staff began identifying various series of records in NARA's custody that could assist them in reconstructing the lost basic service data. With these alternative sources, they could verify military service and provide a Certification of Military Service.… A goal of the NPRC was to have as many of the reconstructed records available to its staff electronically to speed response time to its over one million annual requestors.

Those records included over 9.2 million World War II Army Enlistment Records. These electronic files are available for record-level searching in the Access to Archival Databases utility, and full files are available for download from the National Archives Catalog.

In the 50 years since the fire, technology has also allowed the National Archives to implement and expand its overall digitization plan.

For the agency’s holdings, that process involves scanning, photographing, transcribing, tagging, and adding the metadata that makes files searchable in the National Archives Catalog.

“We hope that by working with the Veterans Administration and other agencies to digitize our holdings, we will be less reliant on access to the paper record and can better serve veterans and their families,” Bosanko said. “In expanding that effort across the federal government, we hope to create a more efficient and effective records environment. The National Archives is driving that change.”

The agency is leading the U.S. Government on digital transformation through the Transition to Electronic Records (PDF: M-19-21 and its 2022 update, M-23-07). This federal policy will emphasize paperless recordkeeping, like using digital technologies, to help other agencies go digital as well. The agency’s Digital Preservation unit works to ensure that digital records are accessible in their hundreds of formats for generations to come.

“The National Archives has made extraordinary efforts to ensure a records catastrophe like the NPRC fire doesn’t happen again,” said Debra Steidel Wall, Deputy Archivist of the United States. “As the nation’s record keeper and one of the largest archival organizations in the world, we hope the lessons we’ve learned from the fire, the policy changes that emerged, and the leadership role we have in digitization and digital transformation are setting the bar for the U.S. government and archival communities around the world.”

PDF files require the free Adobe Reader.

More information on Adobe Acrobat PDF files is available on our Accessibility page.