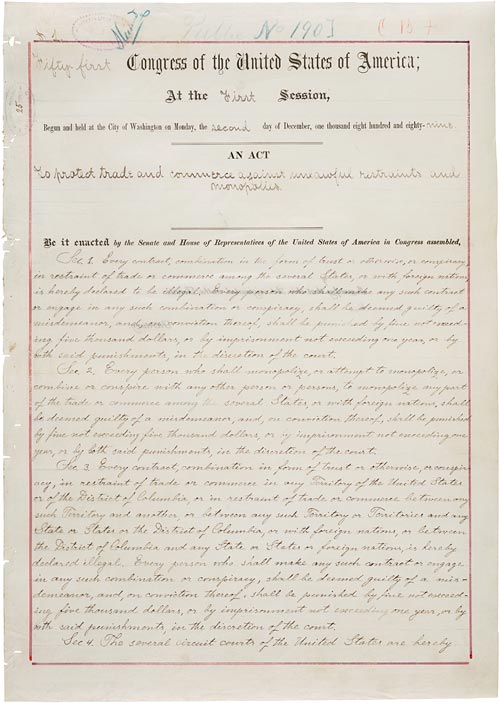

Sherman Anti-Trust Act (1890)

Approved July 2, 1890, The Sherman Anti-Trust Act was the first Federal act that outlawed monopolistic business practices.

The Sherman Anti-trust Act of 1890 was the first measure passed by the U.S. Congress to prohibit trusts. It was named for Senator John Sherman of Ohio, who was a chairman of the Senate finance committee and the Secretary of the Treasury under President Hayes.

Several states had passed similar laws, but they were limited to intrastate businesses. The Sherman Antitrust Act was based on the constitutional power of Congress to regulate interstate commerce. (For more background, see previous milestone documents: the Constitution, Gibbons v. Ogden, and the Interstate Commerce Act.)

The Sherman Anti-Trust Act passed the Senate by a vote of 51–1 on April 8, 1890, and the House by a unanimous vote of 242–0 on June 20, 1890. President Benjamin Harrison signed the bill into law on July 2, 1890.

A trust is an arrangement by which stockholders in several companies transfer their shares to a single set of trustees. In exchange, the stockholders receive a certificate entitling them to a specified share of the consolidated earnings of the jointly managed companies.

Toward the end of the 19th century, trusts come to dominate a number of major industries, destroying competition. For example, on January 2, 1882, the Standard Oil Trust was formed. Attorney Samuel Dodd of Standard Oil first had the idea of a trust. A board of trustees was set up, and all the Standard properties were placed in its hands. Every stockholder received 20 trust certificates for each share of Standard Oil stock. All the profits of the component companies were sent to the nine trustees, who determined the dividends. The nine trustees elected the directors and officers of all the component companies. This allowed Standard Oil to function as a monopoly since the nine trustees ran all the component companies.

The Sherman Anti-Trust Act authorized the federal government to institute proceedings against trusts in order to dissolve them. Any combination "in the form of trust or otherwise that was in restraint of trade or commerce among the several states, or with foreign nations" was declared illegal. Persons forming such combinations were subject to fines of $5,000 and a year in jail. Individuals and companies suffering losses because of trusts were permitted to sue in federal court for triple damages.

The act was designed to restore competition, but it was loosely worded and failed to define such critical terms as "trust," "combination," "conspiracy," and "monopoly." Five years later, the Supreme Court dismantled the act in United States v. E. C. Knight Company (1895). The Court ruled that the American Sugar Refining Company, one of the defendants in the case, had not violated the law even though the company controlled about 98% of all sugar refining in the United States. The Supreme Court reasoned that the company’s control of manufacture did not constitute a control of trade.

The E. C. Knight ruling seemed to end any government regulation of trusts. In spite of this, during President Theodore Roosevelt’s "trust busting" campaigns at the turn of the century, the Sherman Anti-Trust Act was used with considerable success. In 1904, the Supreme Court upheld the government’s suit to dissolve the Northern Securities Company in Northern Securities Co. v. United States. By 1911, President Taft had used the act against the Standard Oil Company and the American Tobacco Company. In the late 1990s, in another effort to ensure a competitive free market system, the federal government used the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, then over 100 years old, against the giant Microsoft computer software company.