Executive Order 9066: Resulting in Japanese-American Incarceration (1942)

Issued by President Franklin Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, this order authorized the forced removal of all persons deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast to "relocation centers" further inland – resulting in the incarceration of Japanese Americans.

Between 1861 and 1940, approximately 275,000 Japanese immigrated to Hawaii and the mainland United States, the majority arriving between 1898 and 1924, when quotas were adopted that ended Asian immigration. Many worked in Hawaiian sugarcane fields as contract laborers. After their contracts expired, a small number remained and opened up shops. Other Japanese immigrants settled on the West Coast of mainland United States, cultivating marginal farmlands and fruit orchards, fishing, and operating small businesses. Their efforts yielded impressive results. Japanese Americans controlled less than 4 percent of California’s farmland in 1940, but they produced more than 10 percent of the total value of the state’s farm resources.

As was the case with other immigrant groups, Japanese Americans settled in ethnic neighborhoods and established schools, houses of worship, and economic and cultural institutions. Ethnic concentration was further increased by real estate agents who would not sell properties to Japanese Americans outside of existing Japanese American enclaves and by a 1913 act passed by the California Assembly restricting land ownership to those eligible to be citizens. In 1922, the U.S. Supreme Court, in Ozawa v. United States, upheld the government’s right to deny U.S. citizenship to Japanese immigrants.

On December 7, 1941, the Empire of Japan attacked the United States at the Pearl Harbor Naval Base in Hawaii. The attack launched a rash of fear about national security, especially on the West Coast. This combined with economic competition, distrust over cultural separateness, and long-standing anti-Asian racism turned into disaster for Japanese Americans.

Lobbyists from western states, many representing competing economic interests or nativist groups, pressured Congress and the President to remove persons of Japanese descent from the west coast, both foreign born (issei – meaning “first generation” of Japanese in the U.S.) and American citizens (nisei – the second generation of Japanese in America, U.S. citizens by birthright.) During congressional committee hearings, Department of Justice representatives raised constitutional and ethical objections to the proposal, so the U.S. Army carried out the task instead.

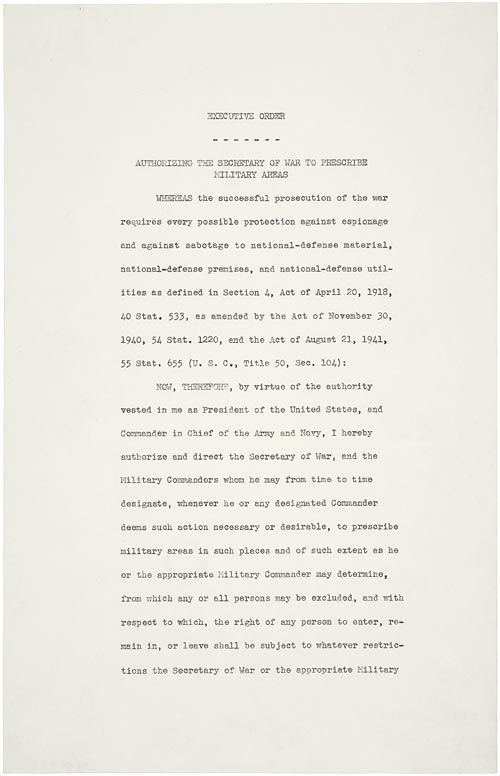

The West Coast was divided into military zones, and on February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 that authorized military commanders to exclude civilians from military areas. Although the language of the order did not specify any ethnic group, Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt of the Western Defense Command proceeded to announce curfews that included only Japanese Americans.

General DeWitt first encouraged voluntary evacuation by Japanese Americans from a limited number of areas. About seven percent of the total Japanese American population in these areas complied. Then on March 29, 1942, under the authority of Roosevelt's executive order, DeWitt issued Public Proclamation No. 4, which began the forced evacuation and detention of Japanese-American West Coast residents on a 48-hour notice. Only a few days prior to the proclamation, on March 21, Congress had passed Public Law 503, which made violation of Executive Order 9066 a misdemeanor punishable by up to one year in prison and a $5,000 fine.

In the next six months, approximately 122,000 men, women, and children were forcibly moved to "assembly centers." They were then evacuated to and confined in isolated, fenced, and guarded "relocation centers," also known as "internment camps." The 10 sites were in remote areas in six western states and Arkansas: Heart Mountain in Wyoming, Tule Lake and Manzanar in California, Topaz in Utah, Poston and Gila River in Arizona, Granada in Colorado, Minidoka in Idaho, and Jerome and Rowher in Arkansas.

Nearly 70,000 of the evacuees were American citizens. The government made no charges against them, nor could they appeal their incarceration. All lost personal liberties; most lost homes and property as well. Although several Japanese Americans challenged the government’s actions in court cases, the Supreme Court upheld their legality. Nisei were nevertheless encouraged to serve in the armed forces, and some were also drafted. Altogether, more than 30,000 Japanese Americans served with distinction during World War II in segregated units.

For many years after the war, various individuals and groups sought compensation for those incarcerated. The speed of the "evacuation" forced many homeowners and businessmen to sell out quickly; total property loss is estimated at $1.3 billion, and net income loss at $2.7 billion (calculated in 1983 dollars based on a congressional commission investigation). The Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act of 1948, with amendments in 1951 and 1965, provided token payments for some property losses. More serious efforts to make amends took place in the early 1980s, when the congressionally established Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians held investigations and made recommendations. As a result, several bills were introduced in Congress from 1984 until 1988. In 1988, Public Law 100-383 acknowledged the injustice of the incarceration, apologized for it, and provided partial restitution – a $20,000 cash payment to each person who was incarcerated.