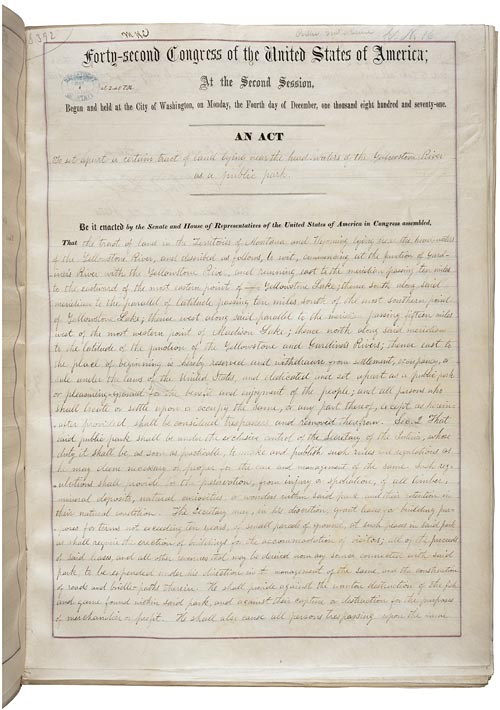

Act Establishing Yellowstone National Park (1872)

Yellowstone became the first Federally protected national park by the Act of Congress signed into law on March 1, 1872.

In the years preceding the Civil War, U.S. government exploration made the nation keenly aware of its western lands. Once the war resolved the question of survival of the Union, the national government turned more attention to its western territory and exploitation of the continent’s wealth. Because the environment of the West differed significantly from that of the East, explorers were charged with identifying natural resources and assessing the utility of the land for settlement.

The U.S. Army was the first in the field. Zebulon Pike, Stephen Long, John C. Fremont and others gave the Corps of Engineers the basis of experience that continued most notably with George M. Wheeler. Even as the Smithsonian Institution and the Department of the Interior expanded their efforts, the Army continued mounting its own surveys until 1879, when all surveys, civilian and military, were consolidated under the U.S. Geological Survey.

Civilian explorers eventually replaced military engineers. On the federal level, Clarence King, John Wesley Powell and Ferdinand Hayden proceeded with the collection of information from the field followed by classification, organization of information, and publications of the findings of their surveys. In addition to the annual reports of the surveys, government explorers disseminated information to the east coast about western environment and geology by lecturing, publishing in scientific and popular journals, giving interviews to newspapers, and providing entrepreneurs with images for duplication on stenographic cards and chromolithographic print sets.

The wide public interest reflected the transformation of American attitude toward the West. Hitherto, for the majority of Americans in the East, the West had been a place to cross over on the way to the Pacific coast or a place of mystery, fearsome in either case. Now it became America’s wonderland.

Photographs and canvasses conveyed the monumental size and geological complexity of the region and enticed viewers to experience its scenic splendors themselves. What historian William Goetzmann calls “the cult of Naturalism” was an extension of the Romantic worldview, where the individual sought out unspoiled wilderness to experience nature’s power first hand. As once tourists had flocked to Niagara Falls to revere the sublime, virtually sacred vista and to revel in the patriotic pride at America’s natural blessing, western sites such as Yosemite and Yellowstone now became popular vacation destinations.

Public knowledge and the popularity of the wilderness paradoxically posed a threat to its survival. The settlement and commercialization of western lands inevitably followed their opening. Leaders of the four major government surveys, while promoting settlement actively, were nonetheless alarmed by the abuses of settlement: monopoly of water rights, speculation by land rings, and mistreatment of Americans Indians on reserved lands. Years before Theodore Roosevelt and the era of Progressives, these public servants formulated guidelines for prevention or reformation of abuse, fought for and erected the structures of bureaus and commissions to advance their agenda, and trained experts in the science and social sciences who would be agents of reform.

One of the most imaginative and uniquely American responses to the endangered wilderness was the invention of the national park system. In 1864, the State of California reserved Yosemite as a parkland. The federal government followed shortly afterward. Early trappers and army explorers had been profoundly impressed by the upper reaches of the Yellowstone River, a region called Colter’s Hell.

Ferdinand Hayden surveyed the area in 1871. Upon his return to the East, he mounted a campaign to promote, but also to protect, the natural wonders he had seen. He quickly wrote a well-received article for Scribner’s Monthly that included fellow expedition member Thomas Moran’s illustrations. He provided Charles Bierstadt, brother to the artist and a leading manufacturer of stereographic cards, with copies of William Jackson’s expedition photographs. He lobbied members of Congress by presenting them with an album of Jackson’s Yellowstone photographs. He was supported in his effort by Jay Cooke, the railroad magnate who anticipated increased tourist ridership on his lines serving the Yellowstone area.

On March 1, 1872, Congress passed into law the act creating Yellowstone “a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.”