D-Day

General Dwight D. Eisenhower was appointed the Supreme Allied Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force during World War II. As leader of all Allied troops in Europe, he led "Operation Overlord," the amphibious invasion of Normandy across the English Channel. Eisenhower faced uncertainty about the operation, but D-Day was a military success, though at a huge cost of military and civilian lives lost, beginning the liberation of Nazi-occupied France. Read more...

Primary Sources

Links go to DocsTeach, the online tool for teaching with documents from the National Archives.

Teaching Activities

The Night Before D-Day on DocsTeach asks students to analyze two documents written by General Dwight Eisenhower before the invasion of Normandy on D-Day: his "In Case of Failure" message and his Order of the Day. Students will compare and contrast these documents to gain a better understanding of the mindset of Allied leaders on the eve of the invasion.

Additional Background Information

During World War II, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill jointly planned strategies for the cooperation and eventual success of the Allied armed forces.

Roosevelt and Churchill agreed early in the war that Germany must be stopped first if success was to be attained in the Pacific. They were repeatedly urged by Stalin to open a "second front" that would alleviate the enormous pressure that Germany's military was exerting on Russia. Large amounts of Soviet territory had been seized by the Germans, and the Soviet population had suffered terrible casualties from the relentless drive towards Moscow. Roosevelt and Churchill promised to invade Europe, but they could not deliver on their promise until many hurdles were overcome.

Almost immediately after France had fallen to the Nazis in 1940, the Allies had planned an assault across the English Channel on the German occupying forces. Initially, though, the United States had far too few soldiers in England for the Allies to mount a successful cross-channel operation.

So in July 1942, Churchill and Roosevelt decided on the goal of occupying North Africa as a springboard to a European invasion from the south. Invading Europe from more than one point would also make it harder for Hitler to resupply and reinforce his divisions. In November, American and British forces under the command of U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower landed at three ports in French Morocco and Algeria. This surprise seizure of Casablanca, Oran, and Algiers came less than a week after the decisive British victory at El Alamein. The stage was set for the expulsion of the Germans from Tunisia in May 1943, the Allied invasion of Sicily and Italy later that summer, and the main assault on France the following year.

At the Quebec Conference in August 1943, Churchill and Roosevelt reaffirmed their plan for a cross-channel assault into occupied France, which was code-named Overlord. Although Churchill acceded begrudgingly to the operation, historians note that the British still harbored persistent doubts about whether Overlord would succeed.

The decision to mount the invasion was cemented at the Tehran Conference held in November and December 1943. Joseph Stalin, on his first trip outside the Soviet Union since 1912, pressed Roosevelt and Churchill for details about the plan, particularly the identity of the Supreme Commander of Overlord. Churchill and Roosevelt told Stalin that the invasion "would be possible" by August 1, 1944, but that no decision had yet been made to name a Supreme Commander. To this latter point, Stalin pointedly rejoined, "Then nothing will come of these operations. Who carries the moral and technical responsibility for this operation?" Churchill and Roosevelt acknowledged the need to name the commander without further delay.

General Eisenhower was named Supreme Allied Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force shortly after the conference ended. When in February 1944 he was ordered to invade the continent, planning for Overlord had been under way for about a year. By May 1944, hundreds of thousands of Allied troops from the United States, Great Britain, France, Canada, and other nations were amassed in southern England and intensively trained for the complicated amphibious action against Normandy. While awaiting deployment orders, they prepared for the assault by practicing with live ammunition.

In addition to the troops, supplies, ships, and planes were also gathered and stockpiled. The largest armada in history, made up of more than 4,000 American, British, and Canadian ships, lay in wait. More than 1,200 planes stood ready to deliver seasoned airborne troops behind enemy lines, to counter German ground resistance as best they could, and to dominate the skies over the impending battle theater. Countless details about weather, topography, and the German forces in France had to be learned before Overlord could be launched in 1944.

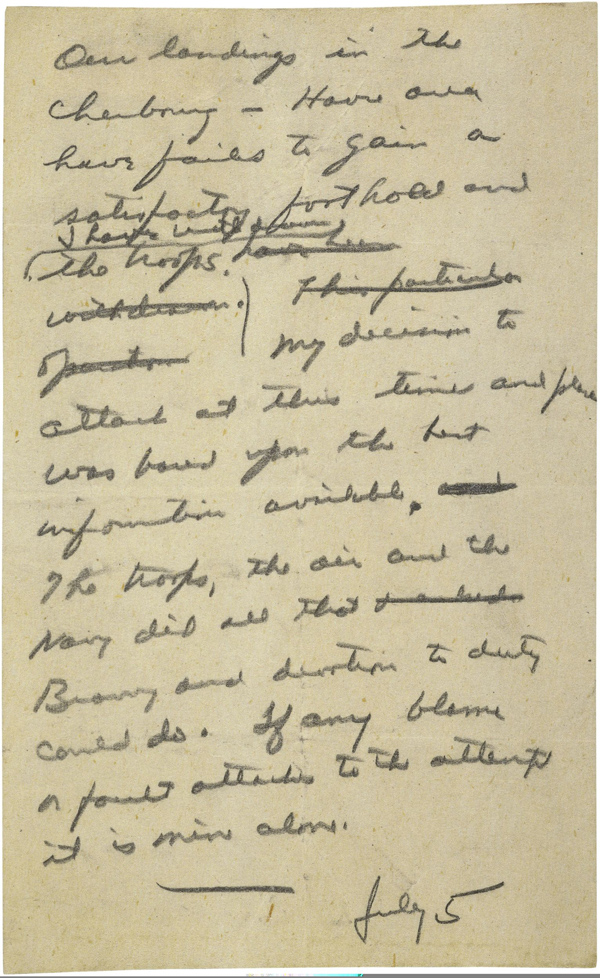

Against a tense backdrop of uncertain weather forecasts, disagreements in strategy, and related timing dilemmas predicated on the need for optimal tidal conditions, Eisenhower decided before dawn on June 5 to proceed with Operation Overlord. But his uncertainty about success in the face of a highly-defended and well-prepared enemy led him to consider what would happen if the invasion of Normandy failed. If the Allies did not secure a strong foothold on D-Day, they would be ordered into a full retreat. Later that day, he scribbled a note intended for release, accepting responsibility for the decision to launch the invasion and full blame, should Overlord fail.

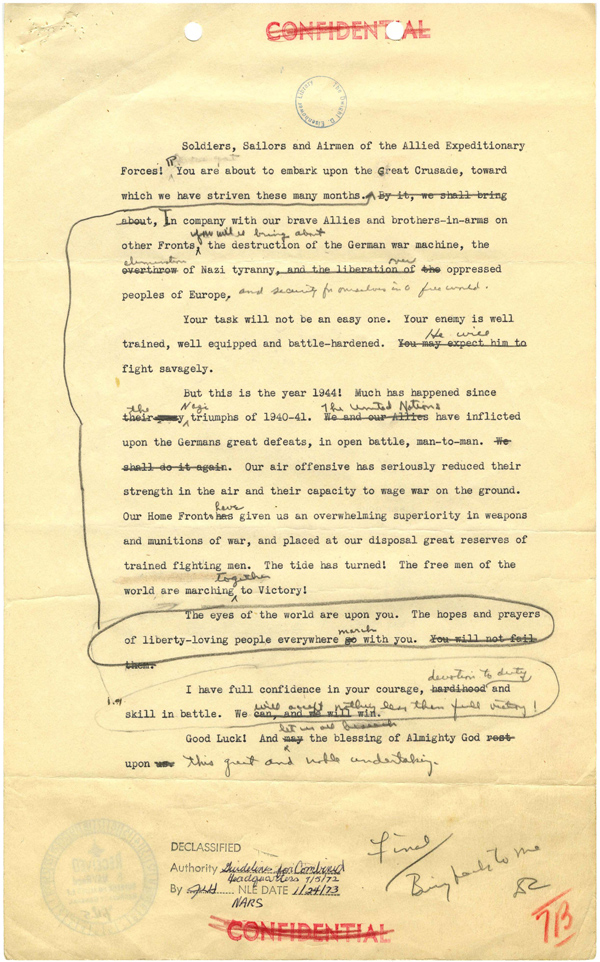

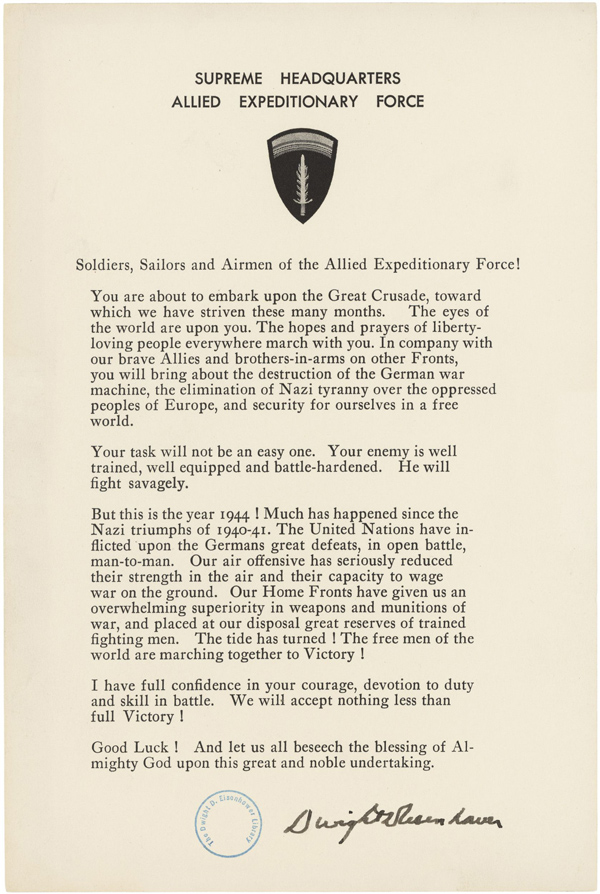

However, Eisenhower's determination that the invasion of Normandy would bring a quick end to the war is obvious in his "order of the day," a message printed and given to the 175,000-member expeditionary force on the eve of the invasion. He had spent weeks carefully drafting the order, which would be distributed to all of the soldiers, sailors and airmen who were to participate. In it, he stated his "full confidence in [their] courage, devotion to duty and skill in battle."

Gen. Eisenhower went to visit Allied troops just before they set off to participate in the assault of occupied France on D-Day. He left his headquarters in Portsmouth, England, and first visited the British 50th Infantry Division and then the U.S. 101st Airborne at Newbury; the latter was predicted to suffer 80 percent casualties. After traveling 90 minutes through the ceaseless flow of troop carriers and trucks, his party arrived unannounced to avoid disrupting the embarkation in progress. The stars on the running board of his automobile had been covered, but the troops recognized "Ike," and word quickly spread of his presence. According to his grandson David Eisenhower, who wrote about the occasion in Eisenhower: At War 1943-1945, the general

...wandered through the formless groups of soldiers, stepping over packs and guns. The faces of the men had been blackened with charcoal and cocoa to protect against glare and to serve as camouflage. He stopped at intervals to talk to the thick clusters of soldiers gathering around him. He asked their names and homes. "Texas, sir!" one replied. "Don't worry, sir, the 101st is on the job and everything will be taken care of in fine shape." Laughter and applause. Another soldier invited Eisenhower down to his ranch after the war. "Where are you from, soldier?" "Missouri, sir." "And you, soldier?" "Texas, sir." Cheers, and the roll call of the states went on, "like a roll of battle honors," one observer wrote, as it unfolded, affirming an "awareness that the General and the men were associated in a great enterprise.

At half past midnight, as Eisenhower returned to his headquarters at Portsmouth, the first C-47s were arriving at their drop zones, commencing the start of "The Longest Day." During the invasion's initial hours, Eisenhower lacked adequate information about its progress. After the broadcast of his communiqué to the French people announcing their liberation, SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) switchboards were overwhelmed with messages from citizens and political officials. SHAEF communications personnel fell 12 hours behind in transcribing radio traffic. In addition, an Army decoding machine broke down.

According to his secretary-chauffeur Kay Summersby, as recounted in David Eisenhower’s book, "Eisenhower spent most of the day in his trailer drinking endless cups of coffee, 'waiting for the reports to come.' Few did, and so Eisenhower gained only sketchy details for most of the day about the British beaches, UTAH and the crisis at OMAHA, where for several hours the fate of the invasion hung in the balance."

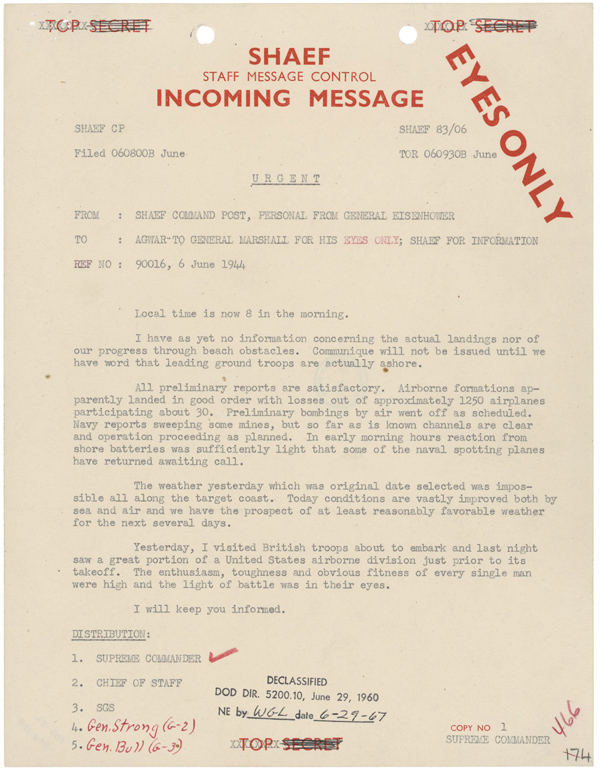

During the early hours of the D-day Normandy invasion, Eisenhower had sent a message to his superior, Army Chief of Staff Gen. George C. Marshall, in Washington, DC. The statement reflects his lack of information about how well the landings were going, even though they were well under way at that moment. Eisenhower reported that preliminary reports were all "satisfactory." At that time, he had received no official information that the "leading ground troops are actually ashore." The incomplete and unofficial reports, however, were encouraging.

Eisenhower's comments concerning the weather speak to the one crucial factor of the invasion over which he held no control. Meteorologists were challenged to accurately predict a highly unstable and severe weather pattern. As he indicated in the message to Marshall, "The weather yesterday which was [the] original date selected was impossible all along the target coast." Eisenhower therefore was forced to make his decision to proceed with a June 6 invasion in the predawn blackness of June 5, while horizontal sheets of rain and gale force winds shuddered through the tent camp. The forecast that the storm would abate proved accurate, as he noted in his message.

Eisenhower's pride and confidence in the battle-tempered men he had met the preceding night—men he was about to send into combat—is also evident in his message. He closed on a confident note, describing the steely readiness of the men he sent to battle, recalling the resoluteness in their faces that he termed "the light of battle...in their eyes." This vivid and stirring memory doubtless heartened him throughout the day until conclusive word reached him that the massive campaign had indeed succeeded.

When the attack began, Allied troops confronted formidable obstacles. Germany had thousands of soldiers dug into bunkers – defended by artillery, mines, tangled barbed wire, machine guns, and other hazards to prevent landing craft from coming ashore.

The cost of military and civilian lives lost on D-Day was high. Allied casualties have been estimated at 10,000 killed, wounded, or missing – over 6,000 of those Americans. But by the end of the day, 155,000 Allied troops were ashore and in control of 80 square miles of the French coast. D-Day was a military success, opening Europe to the Allies and a German surrender less than a year later.

This text was adapted from an article written by David Traill, a teacher at South Fork High School in Stuart, FL, and the article: Schamel, Wynell B. and Richard A. Blondo. "D-day Message from General Eisenhower to General Marshall." Social Education 58, 4 (April/May 1994): 230-232.

Additional Resources

Materials created by the National Archives and Records Administration are in the public domain.

Materials created by the National Archives and Records Administration are in the public domain.

PDF files require the free Adobe Reader.

More information on Adobe Acrobat PDF files is available on our Accessibility page.