The Great War and the New Era

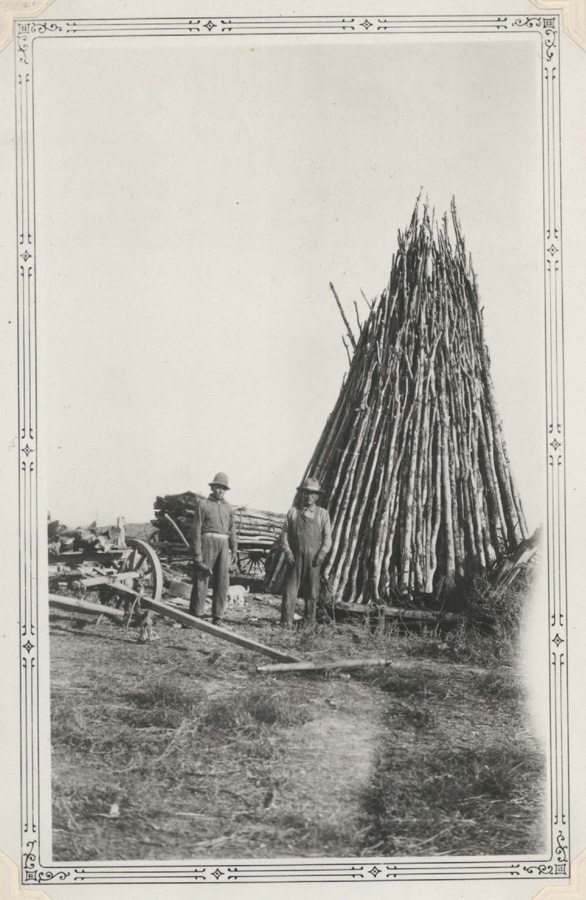

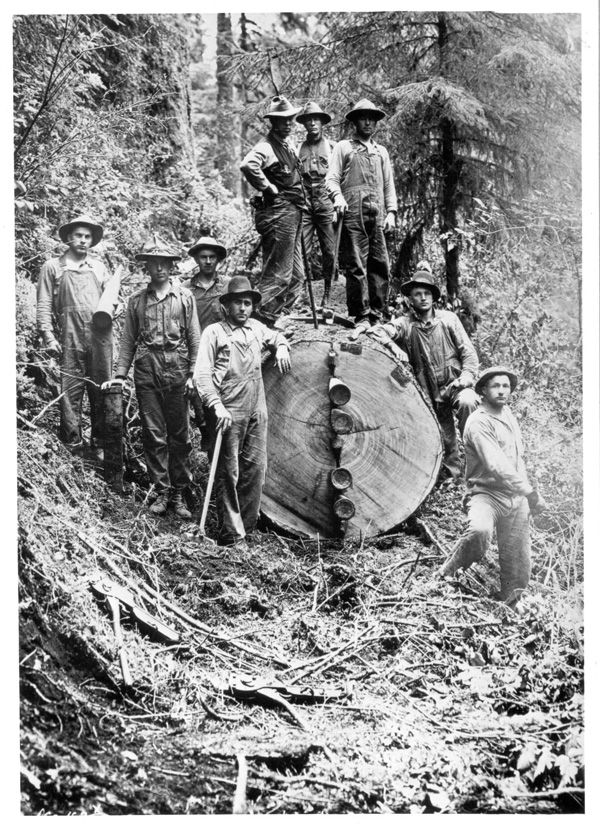

In April 1917 the United States entered World War I against Germany and Austria-Hungary. The Federal Government immediately began to mobilize American society to meet the demands of "total war." The Boeing Airplane Company was established in 1916 in Seattle and by 1918 was building airplanes for the U. S. Navy in support of the war effort. Men who had experience in the logging industry found themselves fighting the war not in the trenches in Europe but in the forests of the Pacific Northwest cutting Sitka spruce destined to be made into airplanes for the U. S. Navy and the newly created Army Air Corps. Women found themselves working in jobs previously closed to them and their contribution to the war effort helped win women the right to vote.

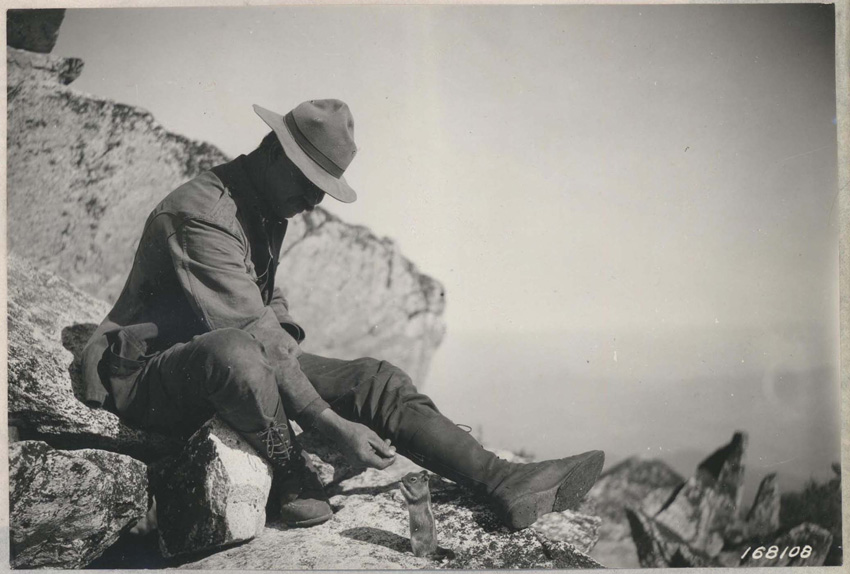

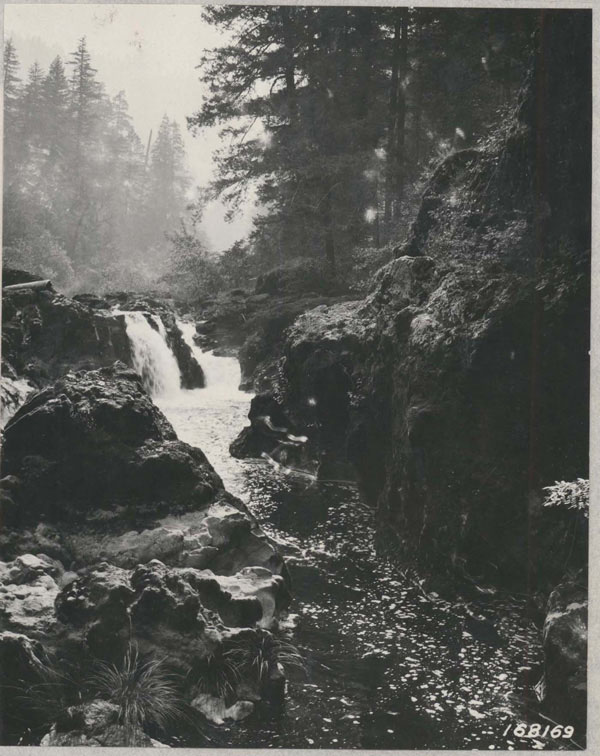

The end of World War I brought a slight depression to the Pacific Northwest with a decline in airplane manufacturing and shipbuilding, but by the early 1920’s many people were experiencing a new prosperity. The trend toward more leisure time combined with more urban living led to the development of outdoor recreational opportunities, as the nation’s forest began to be seen as more than just a stockpile of raw goods. But prosperity did not extend to all groups. Many farmers and minorities groups did not share in the good times. In the Pacific Northwest, Native American tribes tried to hold on to their traditional ways while adapting to technological developments on their reservations.

Interestingly, for a nation that was now predominately urban, during the 1920s government photographers seemed to have concentrated many of their efforts on recording rural life, a trend reflected in the holdings of NARA’s Pacific Alaska Region.