The Great Depression and the New Deal

As the Great Depression ended the prosperity of the 1920s, the Pacific Northwest suffered economic catastrophe like the rest of the country. Businesses and banks failed and by 1933 only about half as many people were working as had been in 1926. The population in the Pacific Northwest continued to grow but more slowly, as many left the Dust Bowl states of the Midwest and Plains.

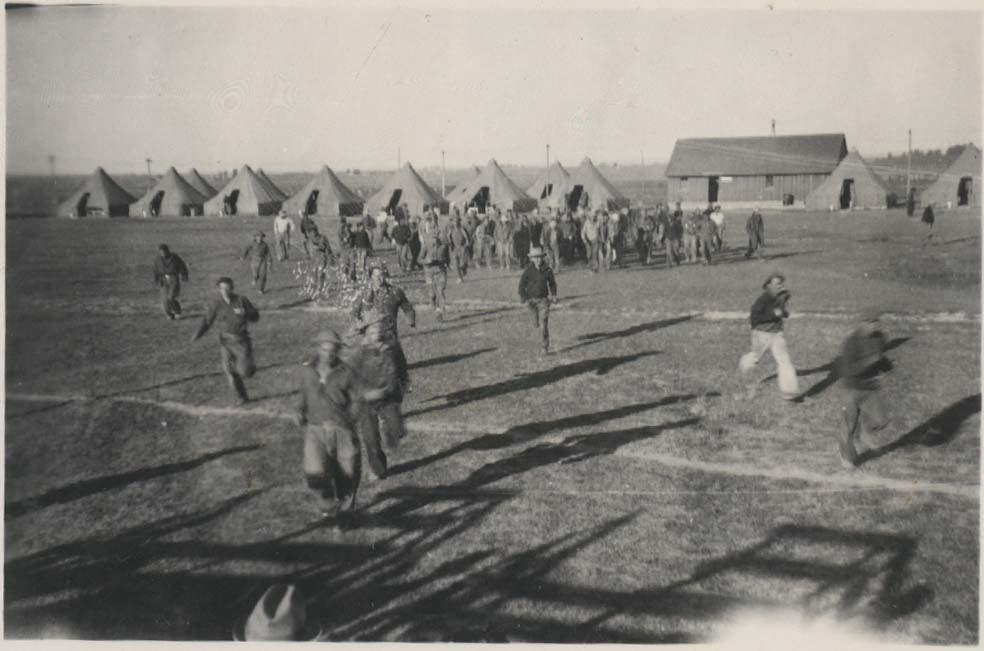

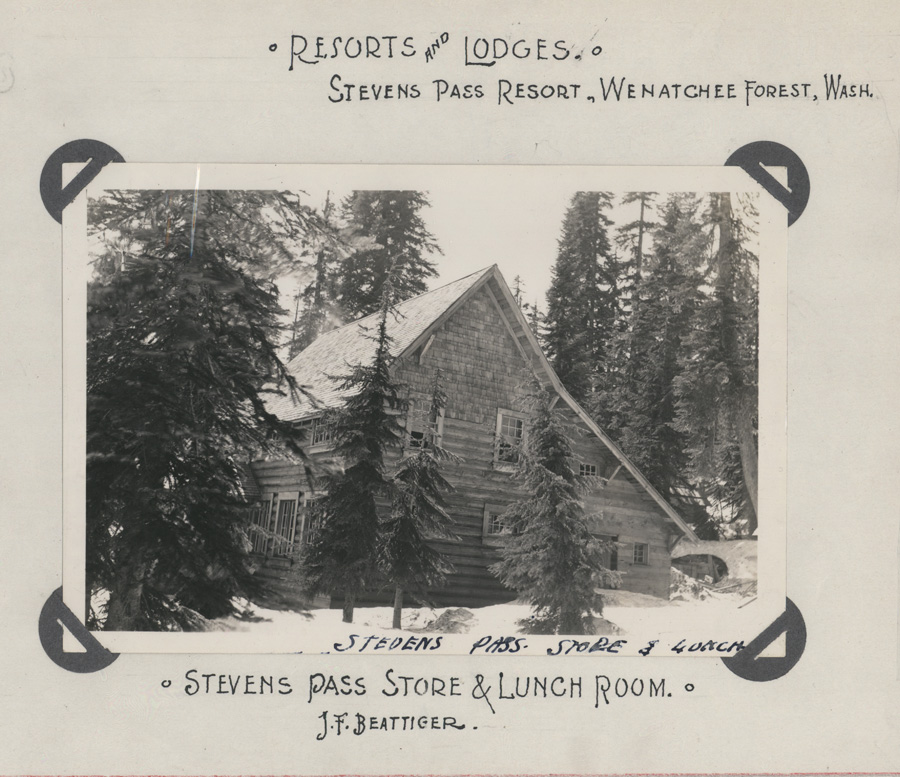

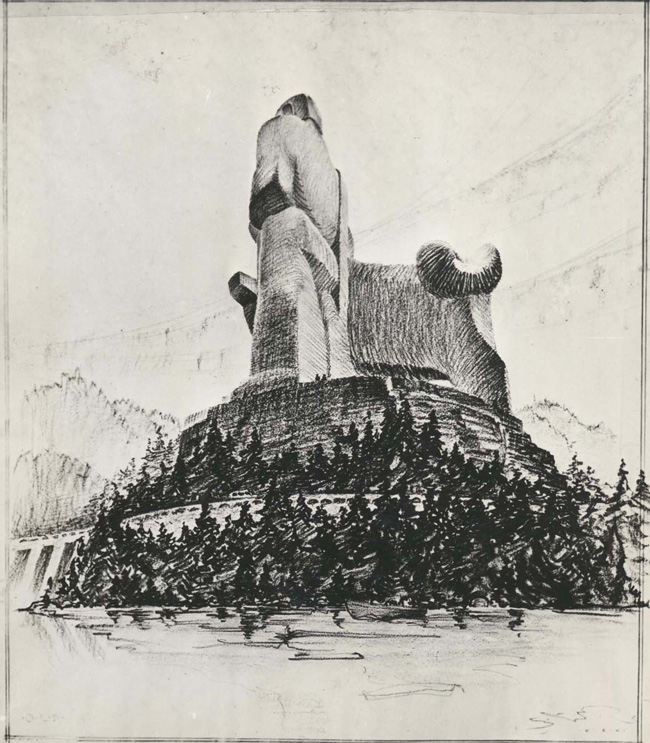

President Franklin D. Roosevelt's "New Deal" aimed at promoting economic recovery and putting Americans back to work through Federal activism. New Federal agencies attempted to control agricultural production, stabilize wages and prices, and create a vast public works program for the unemployed. The West saw the heavy use of Works Progress Administration and Civilian Conservation Corps workers in National Forests and National Parks, and on Indian reservations for work on natural resource related projects and a legacy of buildings, roads, bridges, and trails remains in the Pacific Northwest as a result of these many projects.

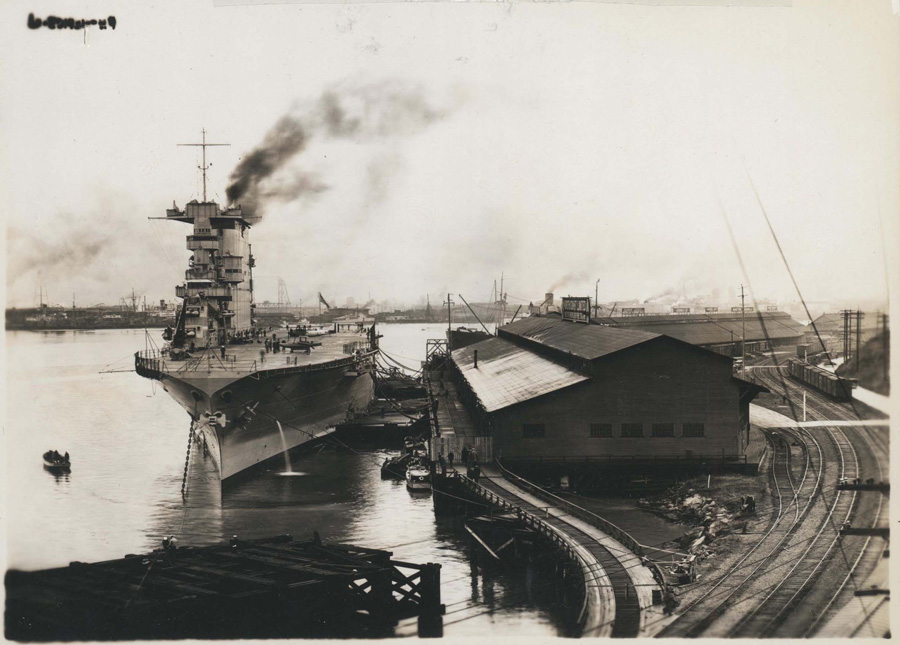

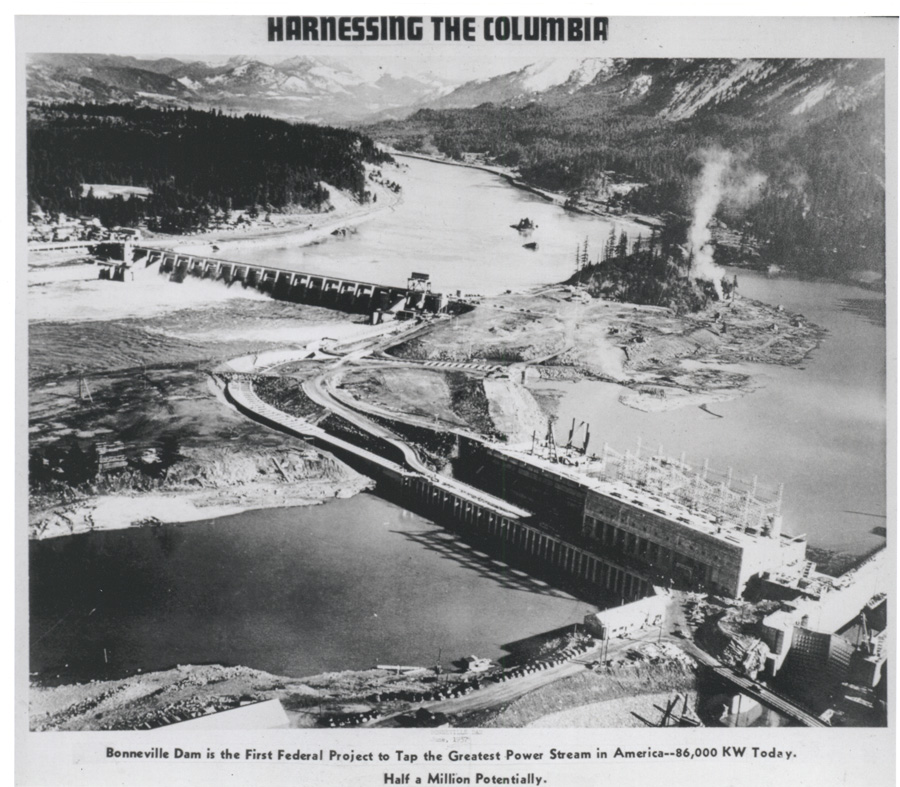

Built in the 1930s and 1940s, Bonneville and Grand Coulee Dams brought electricity to rural areas that were not served by existing utilities. The economy of the Pacific Northwest was strengthened as manufacturing opportunities grew.

Many New Deal-era government agencies sponsored photography projects. Additionally, many agencies were tasked with verbally and photographically documenting projects they undertook. For the most part, these projects used a "documentary" approach that emphasized straightforward scenes of everyday life or the environment. Found attached to the written reports submitted by the various agencies, the images from these projects make for a detailed portrait of America during the 1930s and early 1940s.