20th-Century Veterans' Service Records

Safe, Secure—and Available

Spring 2005, Vol. 37, No. 1

By Norman Eisenberg

The nation is replete with World War II memorials, in small towns and big cities, including the newest one in our nation's capital. But there is just one place that contains personal military information about nearly every American who served in that conflict, as well as those who served at other times during the 20th century: the National Archives and Records Administration's National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) in St. Louis, Missouri.

Like any employer, the U.S. Government maintains the work records of its former employees. For more than four decades, they have been stored in two buildings in St. Louis, one for former members of the military, and one for former members of the civil service. Each facility holds about 2 million cubic feet of records, nearly all of them personnel-related. About 25 percent of the holdings in each building are medical records of active duty military personnel, their dependents, and retirees, from military hospitals and clinics since 1943.

Among the holdings are the World War II Official Military Personnel Files (OMPFs) of former Presidents George H.W. Bush and John F. Kennedy, Gen. Douglas MacArthur and Adm. Chester Nimitz, and Baseball Hall of Famers Ted Williams and Jackie Robinson. These famous figures are just a few of the more than 34 million Americans whose military files are in NPRC's care.

Each year, NPRC's staff of about 600 respond to more than 2 million requests for information, copies of documents, or the return of files to the agencies that created them or to other trusted users. Most of these records are owned by the military services and the Office of Personnel Management and managed under their rules and regulations.

About 100 employees work in the civilian facility, overlooking the Mississippi River near downtown St. Louis. The Official Personnel Folders (OPFs) stored there pertain to most federal civilian employees dating back to the mid-19th century.

Besides the OPFs and health-related records, the building also stores records for the Internal Revenue Service, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Treasury Department. It also serves as a records center depository for federal agencies in the St. Louis area. It holds all the master microfiche of Official Military Personnel Folders created since the mid-1970s.

Recent OPFs contain only documentation of official activities during one's civilian employment, such as position descriptions, promotions, training, and pay adjustments—information more likely of interest to the agency where the person worked and only sometimes to the former employee or that person's family.

Older files contain colorful descriptions of a wide range of government service ranging from Indian agents from the Old West to employees of the Lifesaving and Lighthouse Service. However, information from these records is primarily for official use by government agencies. Selected excerpts are available to the general public if the requester identifies a specific individual and the agency that employed the person.

The military records building, a five-story building about 10 miles northwest of downtown St. Louis, where 500 NPRC staffers work, is a very busy place because of the active nature of military service records.

St. Louis became home to military personnel files after the millions of records created during World War II strained army and navy records storage facilities on the East Coast. In 1950 the Pentagon decided to consolidate all personnel and health records of former service members in St. Louis. Each of the military services managed its own records there. The present building opened in 1956 with the records of the U.S. Army, Navy, and newly independent Air Force. Four years later, the Pentagon reassigned management of these records to the National Archives and Records Service (NARS), within the General Services Administration. Marine Corps personnel records arrived in 1962, the Coast Guard's in 1964.

Stories of America's Defenders

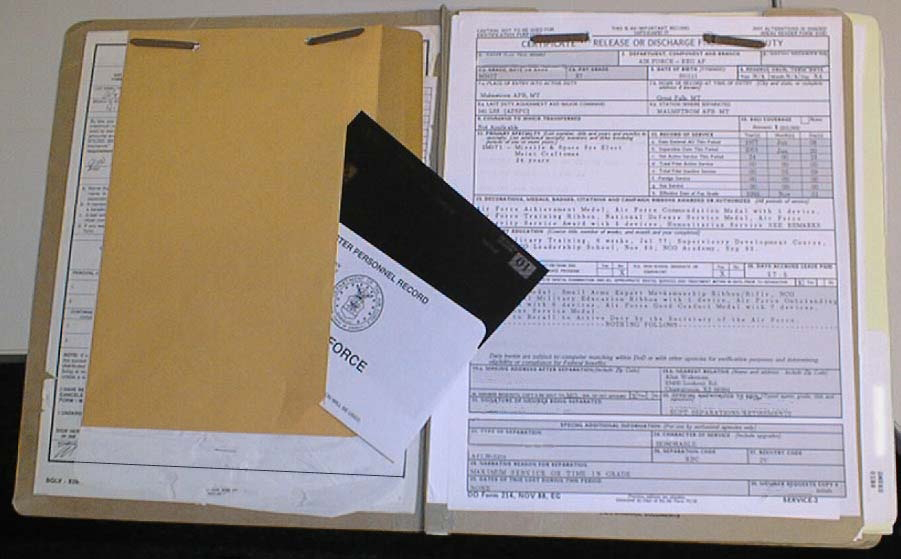

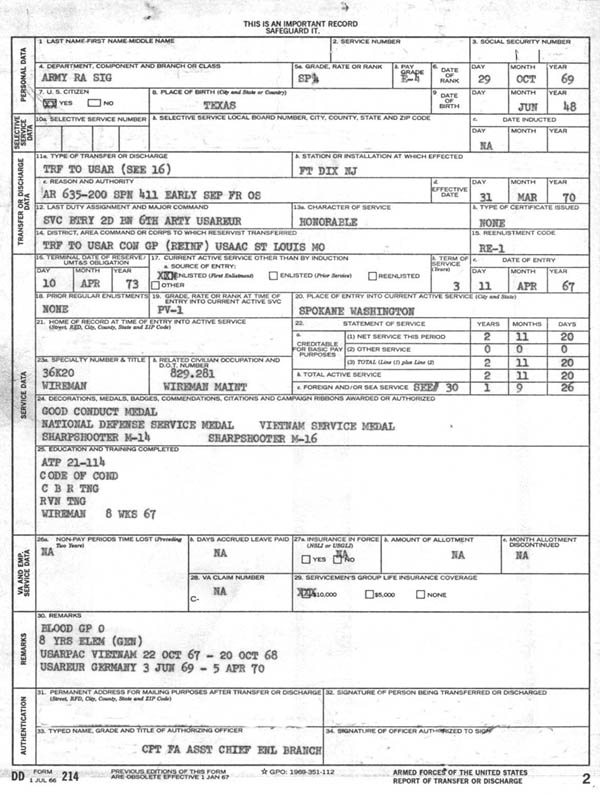

The OMPFs hold the stories of millions of individuals who defended our nation throughout the many wars of the 20th century. They contain such documents as enlistment contracts, duty locations, performance evaluations, award citations, training records, and the especially important Report of Separation (DD Form 214 or earlier equivalent).

NPRC has complete OMPFs for more than 34 million veterans, plus several million more partial files and supplemental records regarding individual military service. Most folders that were retired to the Center before the early 1990s also include records of routine physical exams and outpatient medical and dental treatment. Such health records now go directly to the Department of Veterans Affairs.

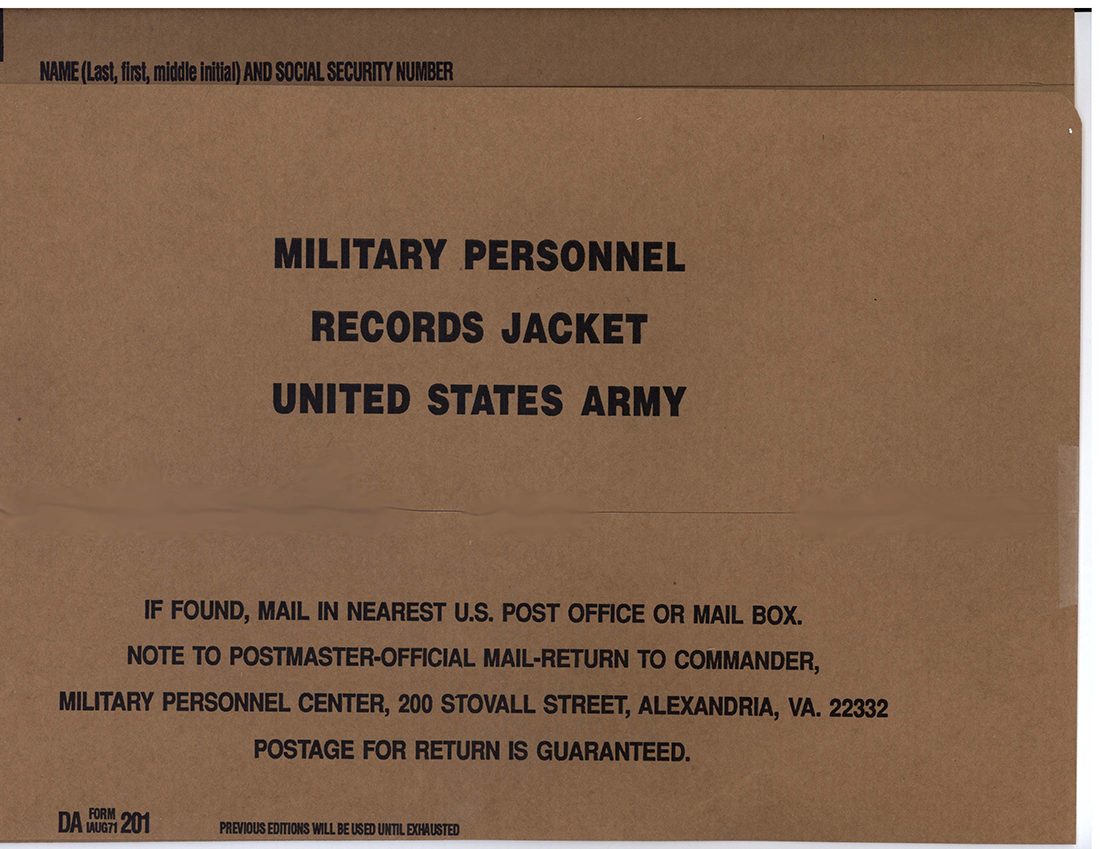

The most common OMPF container is a stiff 12-by-9½-inch brown file folder. Because the army calls its folder Form 201, a popular term for all military personnel folders is "the 201 file." Many of the folders from the past quarter-century contain microfiche images of the personnel documents that were sent to NPRC either in place of the original paper records or with them. OMPFs reside in hundreds of thousands of cubic-foot cardboard boxes on 11-foot-high shelves in immense storage areas.

Surviving a Fire

A fire on July 12, 1973, left the top floor of the military personnel records facility in ruins. This floor had contained some 22 million personnel folders, filed alphabetically, for U.S. Army personnel discharged from 1912 through 1959 and of the U.S. Air Force discharged from September 1947 through 1963. At the time of the fire, one-third of the air force records already had been relocated and thus saved, but overall, fewer than 4 million records were recovered, either entirely or with as little as one identifiable document. A subsequent renovation included frequent firewalls within the storage areas as well as a comprehensive sprinkler system.

Since 1973, NPRC has obtained alternative sources of documents to verify the dates of individual military service and the character of separation for many of the veterans whose files were destroyed. Among these are final pay records, enlistment registers from induction stations, an index of World War II service numbers and dates they were assigned, morning reports, unit rosters, and discharge orders. Many state and federal agencies, particularly the Department of Veterans Affairs, assist NPRC in the reconstruction effort.

NPRC reconstructs a file only after receiving a request involving that veteran, and even then, replacement of an entire folder is impossible for these one-of-a-kind documents. Medical information is especially difficult to replace. NPRC has provided several million reconstruction replies since the fire, but as the number of living veterans from the affected years declines, so has the volume of requests. Nevertheless, NPRC still processes up to 3,000 reconstruction inquiries each week.

Requesting a Record

With only limited exceptions, veterans (or next of kin of deceased veterans) may obtain information or copies of all documents from their own service or health record. Specified government agencies may obtain information they need in their work.

Within the guidelines of applicable laws and regulations, limited information is provided to others who can sufficiently identify the record sought. Anyone who asks for information that is not releasable under those privacy guidelines, such as a prospective employer who wants to know the veteran's character of service ("honorable" for example) or a newspaper that wants to verify extensive service information, must submit the veteran's written authorization.

Veterans, or next of kin if the veteran is deceased, are encouraged to use eVetRecs to submit record inquiries via the Internet. This method helps to expedite the response for those who most often need to verify military service quickly to prove eligibility for benefits. An eVetRecs user must print a signature form, sign and date it, and either fax or mail it to NPRC to activate the request so that their right-to-access can be verified.

A Standard Form 180, Request Pertaining to Military Records, is recommended for requesters who do not use eVetRecs, but even a letter is adequate if it contains the veteran's name, military branch, approximate years of service, Social Security Number, service number (if one was assigned), authorization signature, and date. The SF 180 is available at libraries, VA facilities, and veterans' organizations. It can also be downloaded from the NARA website.

No Electronic Records

NPRC has no electronic military personnel records yet, and contrary to reports last year, the agency has no plans to destroy the paper records that it currently stores. NARA has appraised the OMPFs as permanently valuable historic records of the federal government and on July 8, 2004, accessioned about 1.25 million U.S. Navy and Marine Corps OMPFs, 1885–1939, as archival files. Other OMPFs eventually will be accessioned approximately 62 years after the individual's military service concluded.

Types of Inquiries

Of the 4,000 requests per day, more than 40 percent ask for only a copy of the separation document, the DD Form 214, or its predecessor forms. Packed with important information such as dates and character of service, final rank, awards earned, and military occupation specialty, the separation document is a key to veterans benefits such as home loans, civil service appointments, education, training, and medical care.

NPRC provides certified copies of separation documents within 10 workdays 75 percent of the time. Other popular requests are to obtain copies of health records, replacement or newly authorized service medals, records of one's own (or a family member's) military service, and verification for entitlement for burial in a national cemetery. Cases more complex than simply copying a separation document now typically are worked in about five weeks, although the goal for all requests is 10 working days.

Improved Service

Over the past five years, NPRC's work processes have evolved from the flow of papers to the flow of electrons, and the improvement in service to veterans has been dramatic.

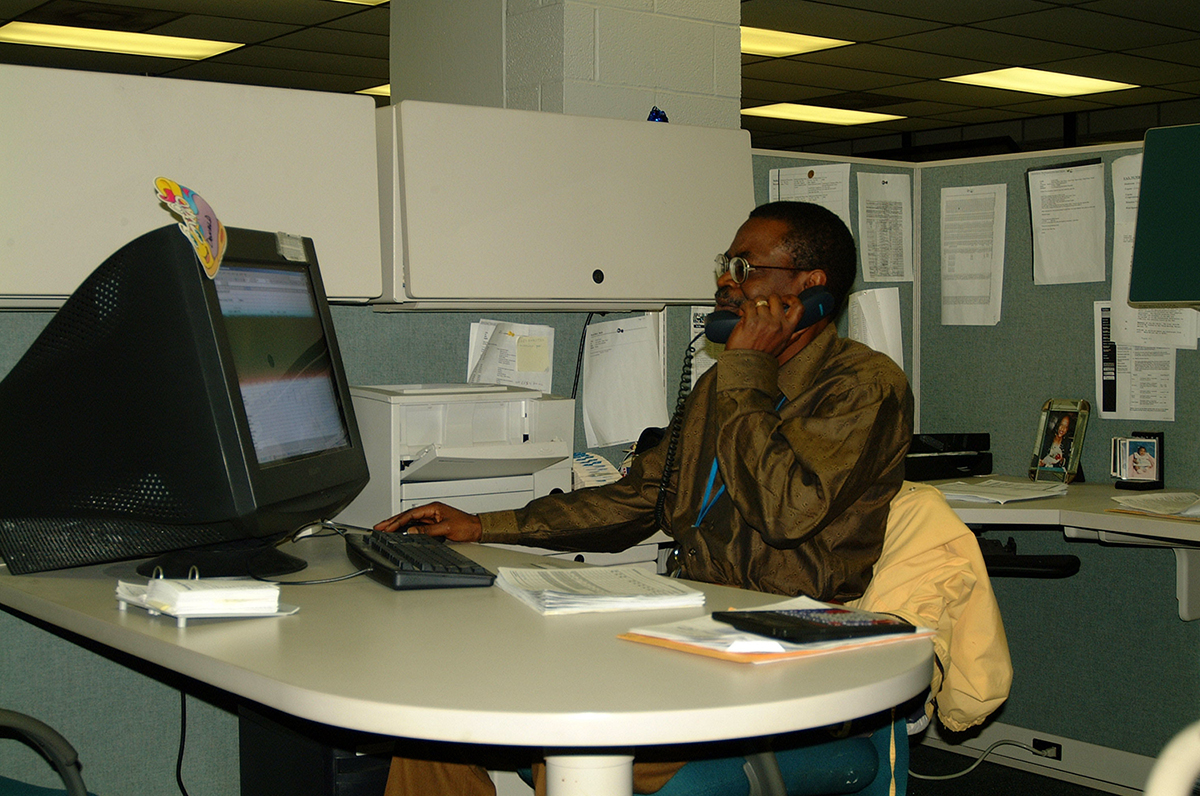

With our new Case Management and Reporting System (CMRS), written inquiries no longer have to be sorted and carried to several places within the building before reaching the person who will prepare the response. Now, NPRC scans each request and keys in pertinent data such as name, service number, branch of service, type of request, and return address. CMRS automatically assigns the request to a technician, and the scanned images are displayed on that technician's computer screen.

At the same time, CMRS identifies the appropriate OMPF to be "pulled" for each request and prints bundles of search request forms for the work unit that pulls OMPFs from the file areas. These forms tell where to find each relevant OMPF and the technician to whom the file should be delivered. The OMPFs are tracked as they move throughout the Center to minimize the occurrence of "missing and misplaced" records.

The designated technician reviews the request and prepares the personalized reply along with the document copies. CMRS keeps a copy of each response for later review and as a record of disclosure. The Center thus retains electronic images pertaining to each case, while collecting summary data about the nature of requests, individual and unit work volumes, and timeliness of replies. This information is used for continuous improvement of the work processes.

Sophisticated case management and a workforce motivated to provide the best possible service are trademarks of NPRC's commitment not only to those who have served, but also to those who want to study their service.

How to Contact the Personnel Records Center

NARA–National Personnel Records Center

(Civilian Personnel Records)

111 Winnebago Street

St. Louis, MO 63118-4199

314-801-9250

NARA–National Personnel Records Center

(Military Personnel Records)

9700 Page Avenue

St. Louis, MO 63132-5100

1 Archives Drive

St. Louis, MO 63138

314-801-0800

On the web: www.archives.gov/st-louis/military-personnel/

Norman Eisenberg is a management analyst at the National Personnel Records Center, where he has worked since 1977. A former U.S. Navy officer, he has provided articles and photographs about NPRC for various NARA publications over the years.