Where’d They Go?

Finding Ancestral Migrations in Federal Records

Prologue, Winter 2014 Vol. 46, no. 4 | Genealogy Notes

By Jean Nudd

We are used to a very mobile society in the 21st century, and we think that it is unique to us.

However, our ancestors were mobile as well. Families were often moving, sometimes across an ocean, but just as often via land routes to the western frontier. Knowing where they went, how they got there, and why they moved can add flavor and depth to our research and family knowledge.

Figuring it all out can be very complicated but fascinating. This article describes a few of the federal records that can be helpful for this type of research.

What Do You Need To Know Before Doing Migration Research?

It’s helpful to know at least where the family started or where they ended up. For example, the Ide family ended up in Vermont, but where did they come from? A Revolutionary War pension file provides the answer to where the soldier was born as well as where his wife and children were born.1

If you can locate the family in a census from 1880 or later, you will find information on not only the person you’re researching but also his or her parents’ places of birth. The 1870 census asks for the number of adult males in the household who are United States citizens, and the 1830 census asked if there were any aliens in the household. If your ancestor was born somewhere other than the United States, those censuses can help you discover if he had become a U.S. citizen. In the case of Jacob Goodman, who was a German immigrant, the 1830 census shows he had become a U.S. citizen.2

Knowing other pieces of information such as land ownership can also help you in your research. Deeds and federal land records can give us ideas of where people lived during certain times. And if they owned land, they are more likely to have made a will that might identify children’s names.

Look into not only where they went or came from, but why they moved. Locating migration routes can uncover information on family relationships, not only how ancestors met one another but also how some lines interconnect.

Let’s start with a simple example of a migration study by using a census record to look at a family that moved a relatively short distance, from Ohio to Iowa. Federal census records are easy to use because a number of websites have made complete indexes available.

What Can a Single Census Sheet Tell Us?

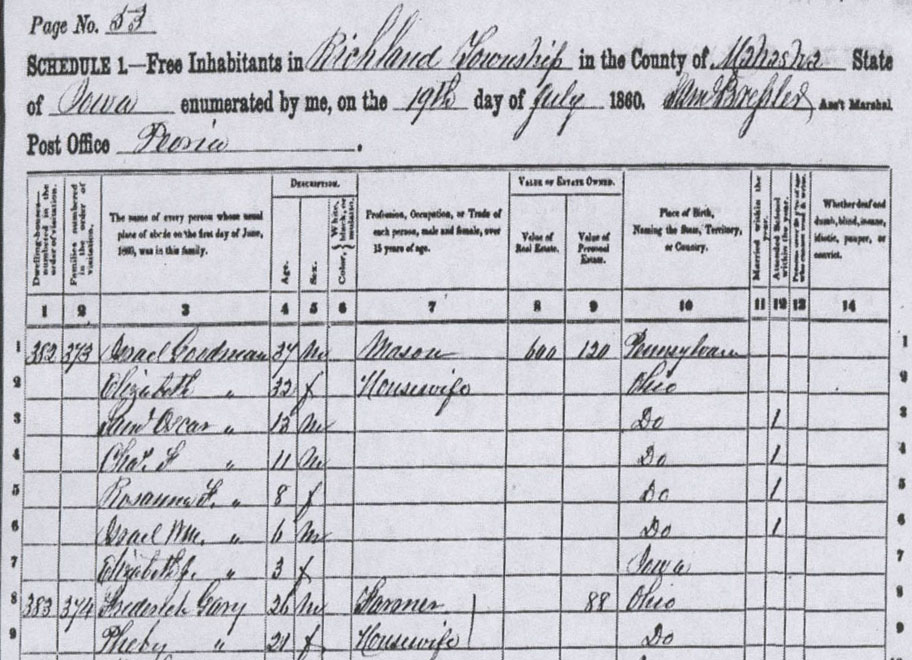

Israel Goodman, born in Pennsylvania in 1824, moved with his parents, Jacob and Roseanna Goodman, to Ohio in the 1830s.3 He married his wife, Elizabeth Finley, in Delaware, Ohio, in 1845.4 On the 1860 census, they are living in Richland, Mahasha County, Iowa.5 The census tells us their children’s names, ages, and places of birth. Samuel was born in Ohio in 1848, Charles in Ohio in 1849, Rosanna about 1852, Israel junior in 1854, and Elizabeth in Iowa in 1857. We can therefore deduce that the family moved from Ohio to Iowa between 1854 and 1857.

Further research in Delaware located a civil suit for nonpayment of a debt by Israel in 1855. The debt was not settled until 1856, so we can further assume that the family did not leave Delaware, Ohio, until 1856.

A more complicated story revolves around Gideon Spencer Wells, who was born in Peacham, Vermont, in 1809.6 He first married Eliza Gilbert, in Forestville, New York, in 1834 and ended up in Wheatland, Michigan, in time for the 1840 census.7 Why did he leave Vermont for Michigan; what route did he travel to get there; and why Michigan rather than some other midwestern state?

One of Gideon’s sons wrote down the family history as far as he knew it. He included some interesting tidbits that answer some of the whys of Gideon’s travels. He says, “From this Michigan home during the fall and winter about 1845 or 46, a visit was made to relatives in New York and Vermont, the trip being in an ordinary farm wagon drawn by a bay and white team. The writer, with his older brother Gilbert, was left at Knowlesville, New York, with their maternal grandmother and Aunt Maria Gilbert, while our parents made the balance of the trip to Vermont and return.”8

What Route Did Gideon Take?

Gideon must have traveled through upper Vermont, through New York, to Forestville, in the southwestern corner of New York, where he married Eliza Gilbert, and ended up in Wheatland, Michigan. The family history tells us his wife’s mother and sister lived in Knowlesville, New York, near Lake Ontario in Orleans County, and that in 1852 Gideon married his second wife, Rachel Hall, in Geneva, Ontario County, New York. He died in Wheatland, Michigan, in 1894. And his life was far from settled!

A map shows us that it is a fairly straight shot from Peacham, Vermont, to Forestville, New York. In fact, the line goes right through Geneva, New York. His trip to Wheatland, overland in a wagon, would be more circuitous as he needed to avoid Lake Erie. But why leave Vermont in the first place?

Finding the answer takes a little more research. Using a wide variety of secondary sources, including histories of Vermont and Peacham as well as books on migration history, we can discover some interesting facts.9

Vermont lost quite a bit of its population during the 1830s and 1840s for a number of reasons, one being that the small-acreage farmers were bought out by large landowners. Vermont was right in the middle of a wool boom, and sheep farmers needed larger acreages. Vermont was also experiencing problems due to the “gradual exhaustion of [their] natural resources” including game, dwindling forests, and soil problems. The federal government had also started to promote western expansion, and newspapers extolled the merits of the west for settlement. Prospective settlers were urged to go west for cheap, fertile land and a healthier climate.10 Often, people do not move independently but as part of a community. Check surnames on the census for both where your family began and where they ended up. For example, the 1820 census for Peacham, Vermont, shows 112 different surnames including Shaw, Robbins, Johnson, Gregory, Eastman, Bailey, and Burbank. When we look at the 1840 census in Wheatland, Michigan, we find these same eight among 118 surnames, indicating that Gideon probably did not move alone.11

How Did Gideon Get to Michigan?

Many Vermonters went west via an all-water route: steamboats to Whitehall on Lake Champlain or packet boats to Troy or Buffalo, and even on to Cleveland, Detroit, and Green Bay. Railroads were not a major factor before 1840 since there were very few of them, and most went only a short distance. However, there was a complex network of “post roads” by this time. And we know from the Wells genealogy that Gideon probably traveled on land.12

What is a post road?

The simplest definition is a road that links two towns. This system of roads was started in 1806 when the U.S. Government created a select committee on post roads under the U.S. Post Office. Post roads were created and maintained to carry the mail from one town to another.13

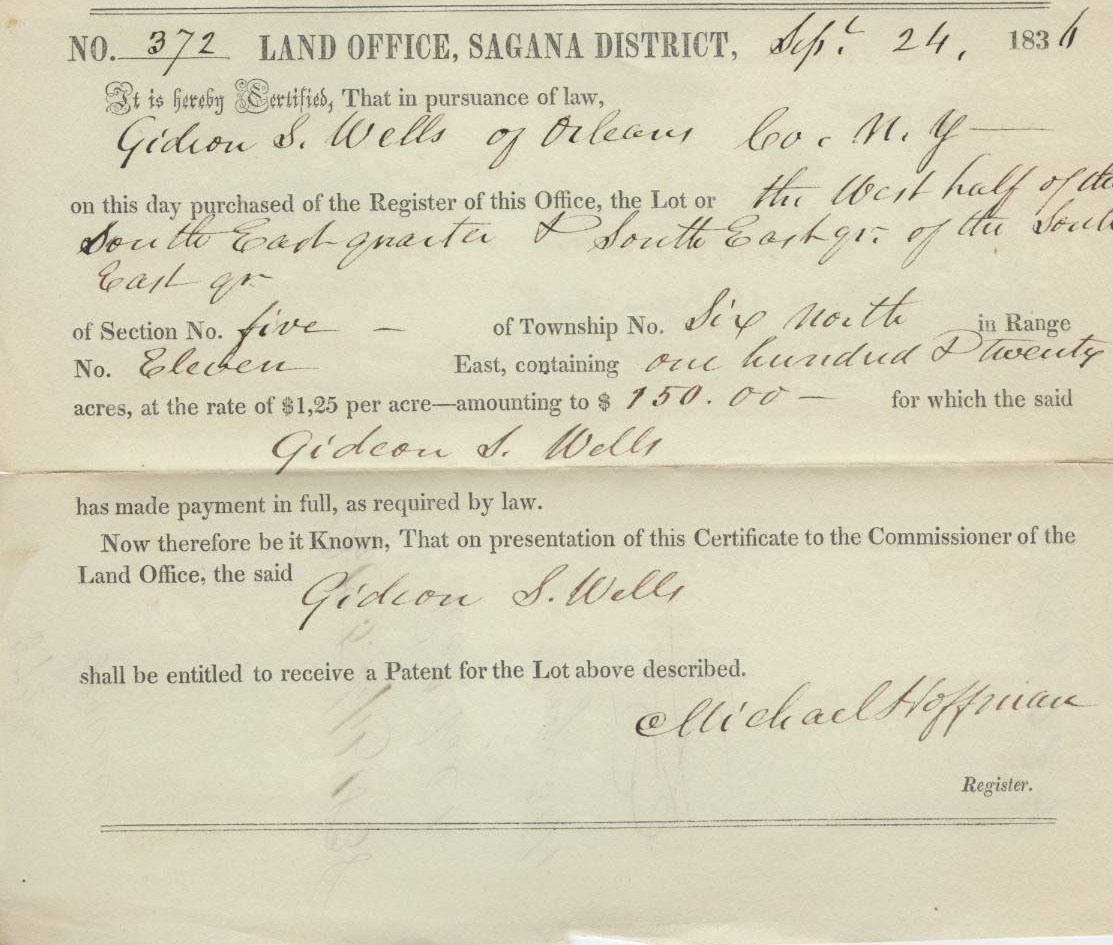

But why Michigan? One reason Gideon and others from Peacham, Vermont, may have chosen Michigan was because land was cheap. In 1820, Congress passed the first federal land sales act. Federal land records are one of the most complete and underutilized records available from the federal government. Some researchers may think that because they do not have any ancestors who “homesteaded,” land records would be of no interest. Since the first homestead act wasn’t passed until 1862, technically Gideon did not homestead, but he did purchase land from the public domain.14

When your ancestor purchased public domain lands determines under which land act the General Land Office (GLO) recorded it. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM), formed after the General Land Office, was the agency responsible for the creation and maintenance of these records. Land entry papers are records created by the GLO to record land patents. These records relate only to the 30 states in which public domain lands were available.15

Beginning in 1783, the United States began selling land to raise money. Around 1800, they started a credit system through which entrymen could purchase land on credit, but this system ended in 1820. These early files give information including buyer’s name, residence at the time of purchase, date of purchase, number of acres purchased, land description, summary of credit payments, and volume and page number of the entry. The 1820 Cash Sale Act meant buyers had to pay cash for the land, and these records contain about the same information except the summary of credit payments. Gideon purchased his land under this act.

Where Can Researchers Locate Land Records?

First, go to glorecords.blm.gov. The database there includes the original patents. Gideon Wells’s patents show his residence when he filed the cash claims and the description of the lands. The 1839 patent shows his residence as Genesee County, Michigan, but the more interesting 1838 patent shows his residence as Orleans County, New York, perhaps living with his in-laws in Knowlesville. The GLO database also has the actual plat books with descriptions of the lands patented. Gideon’s lands were called “bushy, fallow timber lands,” so he probably needed a wagonload of goods to sustain his family while he improved the lands.

And the improvements on the lands can be gauged in the census schedules. In 1850, his land was valued at only $1,200, but by 1860 it had risen in value to $3,600, and by 1870 was up to $7,200.16 We might also check Nonpopulation Census Schedules for Michigan, 1850–1880 (National Archives Microfilm Publication T1164), to get specifics on his crops and farm products as well as his improvements.

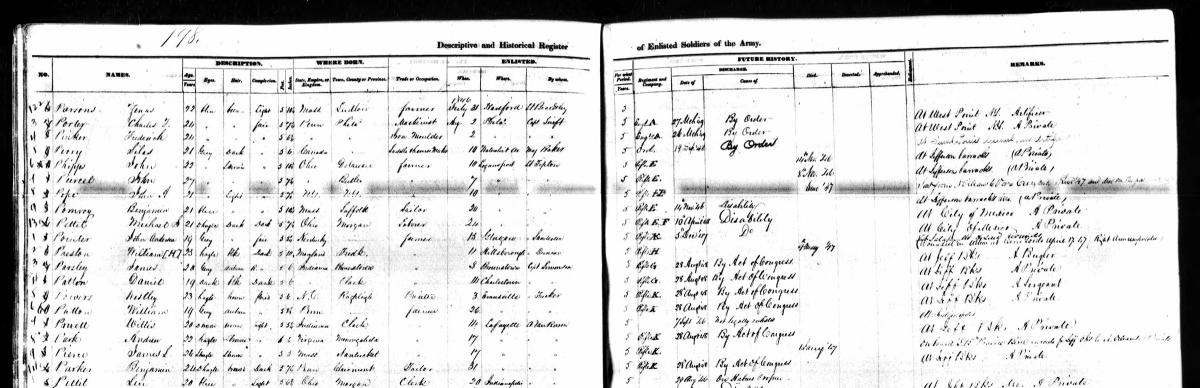

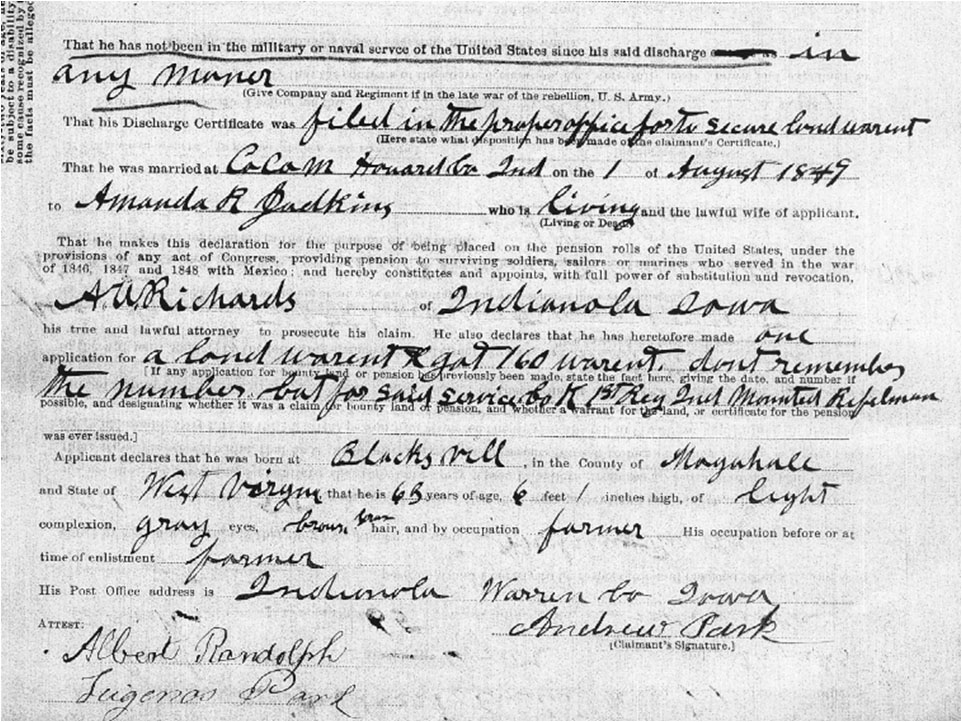

Military pension files are a valuable source for migration research. For example, Andrew Park’s records show that he was born in 1824 in what was then Blackwell, Monongalia County, Virginia, now part of West Virginia. He enlisted in the Army at Lafayette, Indiana, in 1847 and served in the Mexican War. He was discharged at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, in 1849. And he died in Indianola, Iowa, in 1894.17

The Register of Enlistments provides us with his place of birth, height, weight, age, physical description, and occupation as well as when and where he enlisted, regiment, and date and place of discharge.18 His pension file tells us that after his discharge, he went to Cocomo, Howard County, Indiana, before moving to Iowa. It also gives his discharge place and tells us that he received 160 acres of bounty land for his service, which is probably why he moved to Iowa. His widow, Amanda Judkins, tells us on her application that they were married in Alto, Howard County, Indiana, on August 1, 1849, and lived as husband and wife until his death on March 4, 1894, in Indianola. She states again that he had received a bounty land warrant and that he received a pension for his service until his death. And luckiest of all, she gives us her place and date of birth—June 27, 1832, in Wilmington, Ohio.19

The National Archives holds records of bounty land warrant applications in Record Group 15, Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, in hard copy only, not yet digitized. An index of soldiers’ surnames is currently in progress; to date surnames beginning with the letters A through J are complete. Someone looking into the case of Andrew Park would need to do some extra research to locate his record since Park did not record his bounty land warrant number. The description in the Online Public Access database (OPA) tells us that the warrants are arranged in alphabetical order by veteran’s surname, so that should make them easier to search.20

It is possible to find out not only when and where our ancestors moved but also to gain some insight into why they went where they did and what route they may have followed. While it is not always possible to fill in all the details from federal records, land, census, and military records can give us important information into our ancestors’ migrations.

Jean Nudd is an archivist with the National Archives at Boston. She is an avid genealogist and lectures frequently on using federal records and doing genealogy. She has given presentations to the Federation of Genealogical Societies in Boston, New England Regional Genealogical Conferences, and the Ohio Genealogical Society’s annual conference, among many others.

Notes

1. Martha Ide, widow’s pension application #W21431, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files (National Archives Microfilm Publication M804A, roll 1389), Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs Record Group (RG) 15

2. Jacob Goodman household, page 305, Fifth Census United States, 1830 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M19, roll 143), Records of the Bureau of the Census, RG 29.

3. The family is found in the 1830 census in the South Ward of Reading, Pennsylvania, and in the 1840 census in Delaware Township, Delaware County, Ohio, p. 231, Sixth Census of the United States, 1840 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M704, roll 391), RG 29.

4. Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) Delaware City Chapter, “Early Marriage Records of Delaware Co., Ohio” (Delaware, OH: DAR, 1940.

5. Israel Goodman household, Mahasha County, Iowa, population schedules, Richland Township, p. 53, dwelling 382, family 373, Eighth Census of the United States, 1860 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M653, roll 334), RG 29.

6. Unpublished Wells genealogy, p. 2 (in author’s possession).

7.Gideon Wells household, Genesee County, Michigan, population schedules, Wheatland township, p. 64, Sixth Census of the United States, 1840 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M704, roll 205), RG 29.

8. Unpublished Wells genealogy.

9. It’s now possible to find many local histories and genealogy-related books online at sites such as Google Books and Heritage Quest.

10. Lewis D. Stilwell, Migration from Vermont (Rutland, VT: Academy Books, 1948), pp. 151–153, 157–159, 183.

11. Population schedules, Caledonia County, Vermont, town of Peacham, pp. 395–406, Fourth Census of the United States, 1820 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M33, roll 127), RG 29; population schedules, Genesee County, town of Wheatland, pp. 64–75, Sixth Census of the United States, 1840 (National Archives Microfilm publication M704, roll 205), RG 29.

12. Stillwell, Migration from Vermont, p. 185.

13. Committee on Post Offices and Post Roads, 1816–1946, Records of the U.S. Senate, RG 46, National Archives and Records Administration. Use our Online Public Access (OPA) to locate specific records www.archives.gov/research/catalog/.

14. For more information on why many Vermonters, as well as other New Englanders, migrated to Michigan, see Stewart H. Holbrook, “The Land of Michigandia,” in The Yankee Exodus: An Account of Migration from New England, (NY: McMillan Co., 1950), pp. 77–96.

15. Most books on land research have complete explanations of the differences between state land states and public land states and list which states go into each category. See E. Wade Home, Land and Property Research in the United States (Salt Lake City: Ancestry, 1997), pp. 59–60, for state land states; pp. 101–102 for federal (or public) land states. For further information on the General Land Office and land patents, see National Archives and Records Administration, Guide to Genealogical Research in the National Archives (Washington, DC: National Archives Trust Fund Board, 2000), pp. 287–291.

16. Gideon Wells household, Hillsdale County, Michigan, population schedules, Wheatland Township, p. 483, dwelling 183, family 186, Seventh Census of the United States, 1850 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M432, roll 351); Gideon Wells household, 1860 U.S. Census, Hillsdale County, Michigan, population schedules, Wheatland Township, p. 181, dwelling 1303, family 206, Eighth Census of the United States, 1860 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M653, roll 543); Spencer Wells household, Hillsdale County, Michigan, population schedules, Wheatland Township, p. 531, dwelling 187, family 189, Ninth Census of the United States, 1870 (National Archives Microfilm, Publication M593, roll 673).

17. Entry for Andrew Park, Registers of Enlistment in the Regular Army, Mexican War Enlistments, vol. 45, p. 198 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M233, roll 23), Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1780’s–1917, RG 94. Andrew Park pension file, Series 7.2, Pension and Bounty Land Application Files based upon service prior to the Civil War, Mexican War, in order by surname of soldier, Records of the Veterans Administration, RG 15. One of the affidavits filed by his widow gave his date and place of death.

18. The Register of Enlistments is available both on microfilm at various National Archives facilities and online at Ancestry.com.

19. Mexican War service and pension files are indexed on Ancestry. com, but the actual records are not yet digitized and must be ordered from the National Archives. See How to Obtain Copies of Records at www.archives.gov/research/order.

20. Volunteers at the National Archives in Washington, DC, are compiling an index of bounty land warrant applications in RG 15 and have currently indexed soldiers’ surnames beginning with letters A through J. The database is available in the Washington, DC, research room and on Fold3.com. The surrendered bounty land warrants are in the Records of the Bureau of Land Management, RG 49.