Finding the Stones

Summer 2012, Vol. 44, No. 2

National Archives Discovers Several Engravings of the Declaration

By Catherine Nicholson

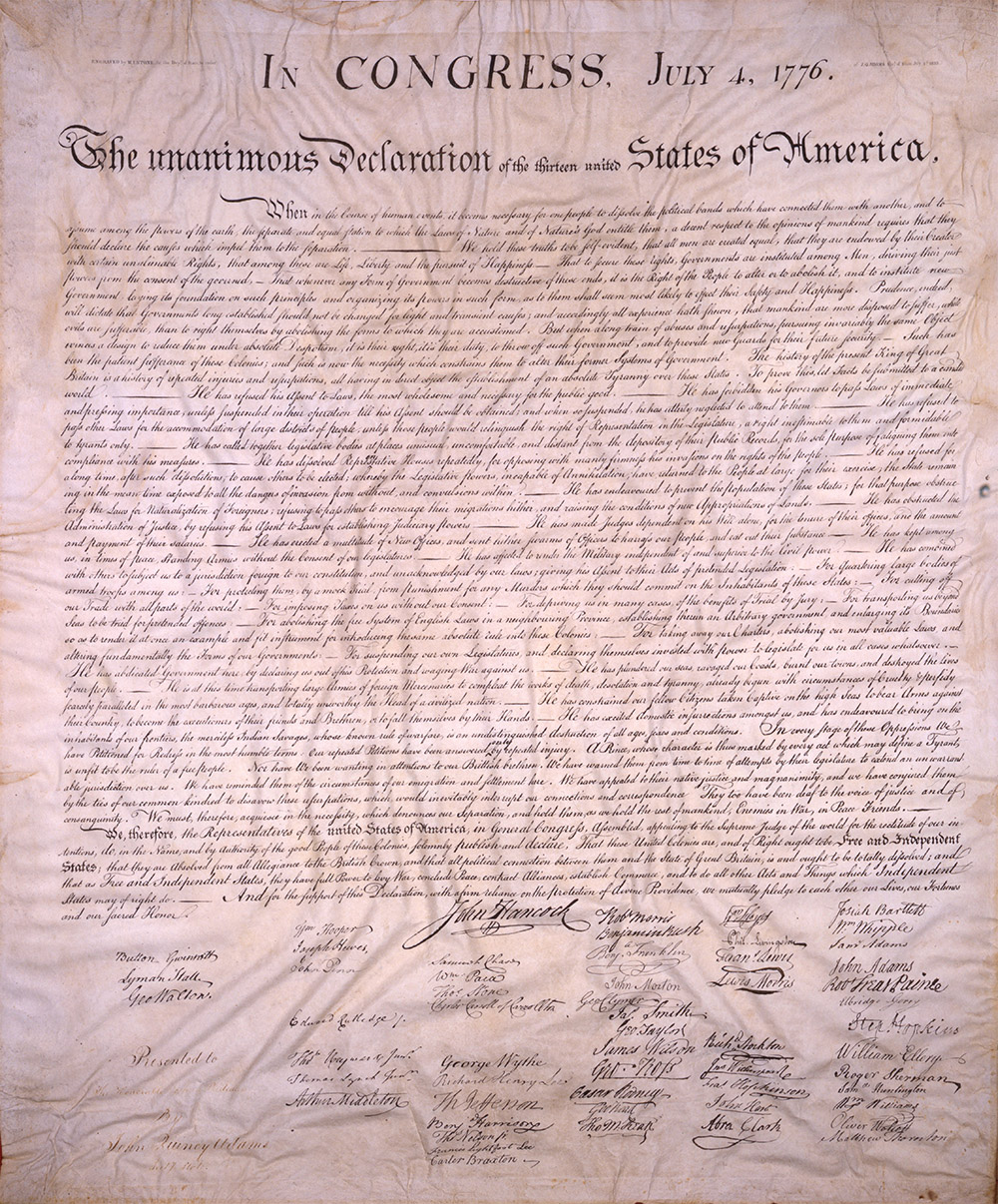

In 1820, John Quincy Adams, then secretary of state and a future President, commissioned a young printer, William J. Stone, to make a full-size facsimile copperplate engraving of the Declaration of Independence.

At the time, the Declaration, signed by 56 individuals (including Adams's own father) from all 13 colonies, was showing signs of age. Adams felt that an engraved copperplate from which copies could be printed would help preserve the historic words of 1776.

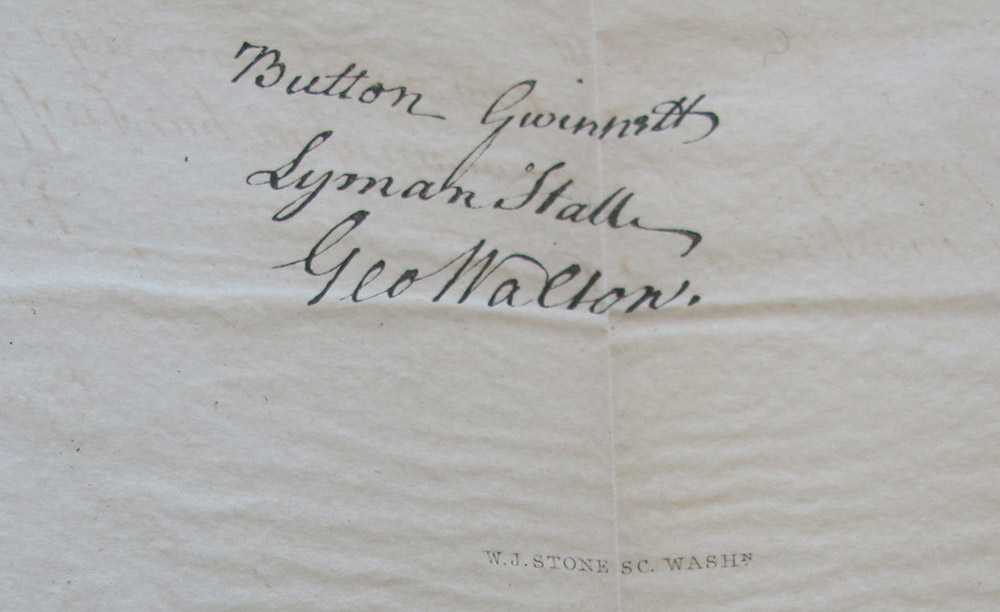

Stone took three years to complete engraving the copperplate, which today is on display at the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C. The plate in 1823 had an imprint line at the top left and top right that read: "ENGRAVED by WILLIAM I. STONE, for the Dept. of State, by order of J. Q. ADAMS, Sec. of State, July 4, 1823." This imprint was later burnished out and replaced with a smaller line at the bottom right that is seen on the copperplate today: "W. J. STONE SC. WASHN."

The prints of the Declaration made from this copperplate are the ones most familiar to Americans, and they provide a clear image of the document that established our nation and allow us to easily read the words of the Founding Fathers and examine their signatures. The original Declaration, more faded than it was in 1820, is on permanent display in the National Archives Rotunda.

Once Stone completed engraving the copperplate in 1823, Congress authorized the printing of 200 copies on parchment and specified the recipients.

Recently, some Stone engravings printed in 1823 and Stone engravings printed later in the 1830s have emerged in the holdings of the National Archives.

Archives Has Significant Holdings of Stone Engravings

Three Stone engravings printed on parchment in 1823 have come to wider attention in the presidential libraries. Four slightly later prints on paper have come to light in the National Archives Library Information Center. One of the parchment engravings has an intriguing inscription that reveals a little-known aspect of John Quincy Adams's campaign for the presidency. These recent discoveries shed new light on the growing esteem in the early 19th century for what is arguably the most important document in American history.

Adams wrote to the president of the Senate in a letter dated January 1, 1824, that "Two hundred copies have been struck off from this plate." The copies were printed not on paper but on parchment to more closely resemble the original Declaration, which was handwritten on parchment. Parchment, made from animal skin and commonly used for diplomas, was preferred for very important documents.

Not long ago, if someone asked if the National Archives had William Stone engravings on parchment of the Declaration, the answer would have been that none were known. A 1991 Manuscripts article by William Coleman titled "Counting the Stones" did not list any engravings on parchment by William Stone at the National Archives.

John Bidwell's "American History in Image and Text," a comprehensive 1989 survey of prints made of the Declaration of Independence, discussed the Stone engraving among other early prints and broadsides of the Declaration. But Bidwell said it had not been determined if the copperplate at the National Archives could be the plate that William Stone had engraved.

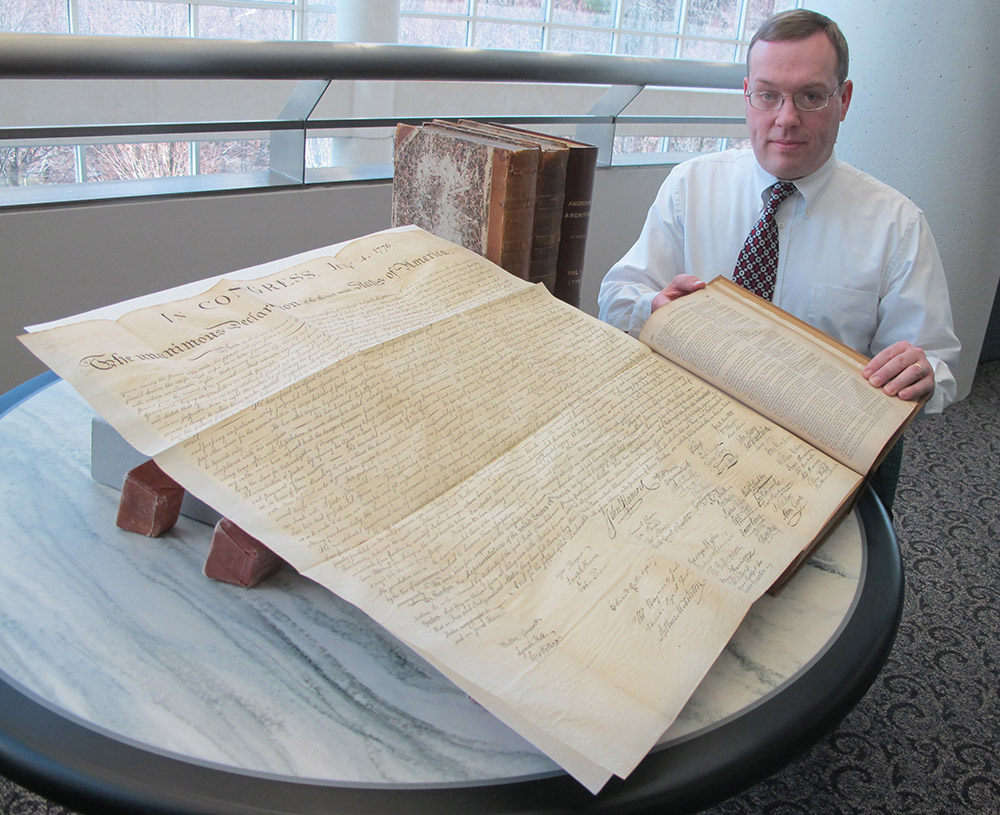

National Archives staff, however, knew otherwise. Elizabeth Hamer, chief of exhibits and publications, recognized the significance of the copperplate transferred to the National Archives from the State Department. She arranged for two experts from the Bureau of Engraving and Printing to examine it in 1951 and confirm it was the plate commissioned by John Quincy Adams. James Gear, director of the preservation division, arranged a printing from the copperplate at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing in 1976, for the bicentennial of the Declaration of Independence and the nation.

A photographer captured the steps in photographs. The master printer carefully heated the plate to remove the wax and paper coating that protected the face of the copper plate. The plate was cleaned and inked carefully to pull six impressions. One was given to the National Park Service for exhibition at Independence Hall in Philadelphia. The remaining impressions remained in safekeeping at the National Archives.

A 2003 article in Prologue discussed the copperplate and noted that Stone's elderly widow, Elizabeth Jane Stone, donated his personal impression on parchment to the Smithsonian Institution along with other historic items in the 1880s. In 2004, Stone's engraved copperplate was put on exhibition at the National Archives next to one of the 1976 impressions. While the copperplate and the 1976 prints were at the National Archives, no one was aware that the National Archives had any 19th-century prints from the copperplate.

Uncovering the Stones Around the Archives

Today, heightened interest in William Stone engravings of the Declaration of Independence has brought into prominence several other Stone engravings at the National Archives.

This story began with a visit to the Richard Nixon Presidential Library as it prepared to become part of the National Archives and Records Administration in 2007. A Stone engraving on parchment on display there was a treasured print given to the then-private library in 1992 by the Wrights, a family with roots in Maryland. The parchment's folded-under edges had glue residue and an embedded splinter, evidence of its past mounting around a wooden support. This print is displayed at the library each year on the Fourth of July and for other major holidays.

An unusual inscription at the bottom left of the Nixon Library's engraving said it was presented by Secretary of State John Q. Adams to Joshua Prideaux. Bold cursive letters read "Presented to/ the Honorable /By/John Quincy Adams/Sect of State." The name "The Honorable Joshua Prideaux" was written in a second smaller hand, in faint ink, below the words "Presented to."

The Prideaux name likely refers to a politician and Maryland presidential elector in 1820, according to Nixon Library curator Olivia Anastasiadis, interviews with the Wright family, and research by docent Jo Lyons. The inscription shows John Quincy Adams reaching out to politicians before the hotly contested presidential election of 1824, which was resolved in the House of Representatives on February 9, 1825.

Adams also presented a Stone engraving to Maryland politician Thomas Emory, according to an annotation on another engraving in private hands. Both recipients were members of the Maryland Executive Council in 1824. Emory was also elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1824 and later was a Maryland elector in the 1828 presidential election. The annotation on the engraving presented to Emory was handwritten in a very different style, possibly by the recipient, with small tight printing near the bottom left corner: "Presented by the Hon. J. Q. Adams, Sec. of State of the U.S. to Thomas Emory, President of the Executive Council of Md. 1824."

Another Stone engraving, previously in the collection of William Coleman, also bore an inscription for presentation by John Quincy Adams but without a name inserted. The style and wording of this incomplete inscription closely matches that on the Stone engraving in the Nixon Library.

This group of Stone engravings shows John Quincy Adams politicking for the presidency by presenting or being ready to present Stone engravings to politicians beyond those authorized explicitly by the May 26, 1824, joint resolution of Congress: the three surviving signers John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Charles Carroll of Carrollton; the Marquis de Lafayette (who visited Washington, D.C., in late 1824); the President; the Vice President; the Supreme Court; the President's House; departments of the federal government; governors of the states and territories; universities; and a few others. These engravings authorized for distribution were not inscribed but were accompanied by a letter to the recipient.

Adams's presentation of Stone engravings to Maryland politicians probably reflects an awareness that the state's electoral votes would be difficult to win, as most of his support was in New England. In 1824, Maryland's electors supported Andrew Jackson with seven votes, while Adams garnered only three.

Jackson received a plurality of the national electoral votes, but not the majority required by the Constitution. The election then went to the U.S. House of Representatives, where the Maryland delegation supported Adams with five votes to three votes for Jackson. Adams became President with the votes of 13 of the 24 state delegations in the House.

In 1828, Maryland's electoral votes split six for Adams to five for Jackson, but Jackson won the majority of national electoral votes to become President. One can only speculate if the Stone engravings that Adams presented to influential politicians such as Prideaux and Emory had any impact on the presidential electoral vote in 1824 or 1828. Prideaux was an elector in 1820 While Emory was elected to the House of Representatives in 1824, he did not take his seat until after the February 1825 vote, according to practice of that era.

The Search for More Engravings Becomes a Treasure Hunt

Excited by the noteworthy engraving at the Richard Nixon Presidential Library, Archives staff contacted all the presidential libraries to ask if they might have a Stone engraving. Soon the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library confirmed that it had a William Stone engraving printed on parchment. This impression had no inscription on the front and was framed, so it was not possible to see if there was an annotation on the reverse. Esther Snyder gave it to the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation, and it is exhibited on special occasions at the Reagan Library.

Inquiry at the John F. Kennedy Library revealed a Stone engraving given to President John F. Kennedy early in his term. This folded parchment retained dust and grime of long storage, possibly in an attic. It had cuts and punctures with old repairs and was in no condition to display. But staff saw its significance and potential for exhibition for special events. The Kennedy Library arranged for careful conservation treatment that allowed it to be unveiled and put on display for July 4, 2010.

Still more Stone engravings have recently come to light. In the National Archives library, Jeffery Hartley located four volumes published in 1848 with a Stone engraving inserted in each. They were from a series of volumes titled American Archives, published by Peter Force, a colleague and friend of William Stone. Their collaboration to reprint the copperplate resulted in many new prints on paper, often called Force prints.

After making his mark with the facsimile engraving of the Declaration of Independence, William Stone developed a prosperous business printing maps for government agencies as the young country expanded westward. His maps show a design sense that makes them handsome as well as utilitarian. He owned a grand house and more than 200 acres of land above the northern boundary of the city of Washington. Stone studied with sculptor Hiram Powers while he lived in Washington for a few years after 1834, creating portrait busts of political figures. Around this time, Powers must have sculpted a marble bust of Stone. The portrait bust, displayed in the atrium of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, shows him as a handsome man in midlife.

Like William Stone, Force became a printer in Washington after having learned the trade as a young man in the New York City area. Force was engaged in politics and was a strong ally of John Quincy Adams, as was Stone.

Force had employed the young Stone to make prints for his publications such as A National Calendar, which began publication in 1820. Work for Force's publications helped Stone pay bills and support his family while he undertook the lengthy work of engraving the Declaration of Independence.

Force collected manuscripts and historical records and envisioned publishing a vast collection of transcribed manuscripts relating to the history of the American colonies. He approached Congress to get official authorization and sponsorship to publish a series of volumes called American Archives.

In 1833 Congress authorized publishing up to 1,500 copies of the series under contract to the Department of State. Force knew of the copperplate of the Declaration of Independence his friend had engraved, stored unused at the Department of State, and planned to insert folded prints of the Declaration into the publication. After the project was authorized, Force arranged for Stone to make prints from the copperplate.

Meanwhile, Force was elected mayor of Washington. The American Archives,Fourth Series, volume 1, appeared in December 1837 during his first term of office. In November 1839 he approved payment of $1,524.74 by the secretary of the Treasury to William Stone for printing from the Stone copperplate. The reprinting must have been completed when Force authorized the Treasury to pay Stone this significant sum of money. In 1848, the Fifth Series, volume 1, was published with the Stone engraving of the Declaration of Independence inserted into the text. The "Force" printing was on a translucent tracing paper. Sometimes mistakenly called "rice paper," it was a machine-made Western paper. Each print was inserted along its right edge into the binding and neatly folded in. The print had a new imprint line at the bottom left corner that read "W.J. STONE SC. WASHN."

Stone's Copperplate Is Transferred to the National Archives in the 1950s

Some people thought that the changed imprint and its different appearance on slick paper meant that the Force print was a completely new one. Others said that the Force facsimile was a lithograph because the copperplate would be too worn to pull hundreds of impressions. The copperplate at the National Archives, however, shows the imprint "W.J. STONE SC. WASHN." in the correct corner of the copperplate (at bottom right, as the engraved copper is a mirror image of the print itself). The simplest explanation was that the original imprint line on the 1823 engraved plate had been removed by burnishing, leaving tool marks on the reverse, as experts from the Bureau of Engraving and Printing verified in their 1951 examination. The new imprint line was added near the plate's bottom corner and is precisely the imprint line seen on the Peter Force printing.

The number of impressions printed was large, a few thousand. But the publication did not sell as many copies as hoped. In 1853 Secretary of State William Learned Marcy abruptly canceled the State Department contract to publish the remaining series of American Archives, with only the Fourth and Fifth Series printed. The State Department distributed many copies to the libraries of embassies and government agencies as an official government document. American Archives volumes in the National Archives library have bookplates or library stamps indicating that they had been in government libraries for the U.S. Embassy of Chile, the Department of Commerce, and the War Department.

In the mid-20th century, some of these volumes were deemed surplus (one volume is stamped "DISCARD") and made available to other government libraries. Several volumes were readily accepted at the National Archives. Two American Archives volumes retained their original 1848 gold-tooled quarter-leather brown binding with red and brown marbled paper on the covers and endpapers. A third volume is recased with modern buckram-covered boards, but it retains the 1848 original marbled paper flyleaves and the intact text block.

The fourth volume is in an original binding, but from some time later, around 1900. In this volume, the print was inserted so it unfolds down from the text, while in the earlier binding, the prints unfold upwards. This later binding suggests that unbound printed text may have been stored, as well as extra impressions of the Stone engraving, and bound later as needed for distribution.

American Archives was an ambitious venture. Not all the impressions of the Force printing were ultimately used, and some were never folded. John Sherwood, a former reporter for the Washington Star,covered the 1970 liquidation of W. H. Lowdermilk antiquarian book store in Washington, D.C. The store book labels described its stock as "Second-Hand Books/Government Publications."

The store inventory in 1970 still included treasures like albumen photographs from 19th-century Western expeditionary surveys that were bought by libraries such as Duke University Library. Sherwood noticed a group of never-folded Force prints for sale. Advised by an archivist to buy some, he was able to afford only one. From time to time, other unfolded impressions are offered for sale.

William Stone's relationship with Peter Force was more than a business arrangement. In 1841 Stone and Force were founding members, with John Q. Adams, Daniel Webster, and 12 others, of the National Institute for the Promotion of Science, which was subsumed by the Smithsonian Institution. When Stone died in 1865, Peter Force was a pall-bearer. Stone was buried in Rock Creek cemetery after a well-attended funeral at St. John's Church on Lafayette Square. Force sold his significant manuscript collection to the Library of Congress in 1867, the year before his own death. Force was also buried in Rock Creek cemetery with an unusual memorial that features a carving of a shelf of American Archives volumes.

Visitors to the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C., can see a framed 1823 Stone engraving on parchment on display, lent courtesy of David Rubenstein, next to Stone's copperplate, and a 1976 print also made from it in the National Archives Experience exhibition.

Catherine Nicholson is supervisory conservator in the NARA conservation labs. She has a B.A. from Brown University and an M.S. from the University of Delaware/Winterthur Museum program. She has worked at the Boston Public Library, the Smithsonian Institution, the National Gallery of Art, and the National Archives. She has a special interest in and has written on paper history and watermarks, as well as the William Stone engraving of the Declaration of Independence.