All for a Sword

The Military Treason Trial of Sarah Hutchins

Spring 2012, Vol. 44, No. 1

By Jonathan W. White

© 2012 by Jonathan W. White

Revised June 27, 2012

Gettysburg is perhaps the most famous battle in American history.

On the first three days of July 1863, some 160,000 Union and Confederate troops engaged in a bloody combat that is sometimes called the "High-Water Mark of the Confederacy." Upward of 51,000 Union and Confederate soldiers were killed, wounded, or missing. Piles of amputated limbs littered the field, and bodies lay strewn across the land awaiting burial. More than 160 field hospitals were hastily set up in tents, homes, barns, churches, and other buildings throughout the area.

At a building known as the College Edifice at Pennsylvania College (now an administrative office building at Gettysburg College), some 900 rebel soldiers lay wounded, awaiting medical attention. One student was shocked by what he saw:

"All rooms, halls, and hallways, were occupied with the poor deluded sons of the South," he wrote. "The moans, prayers and shrieks of the wounded and dying were heard everywhere."

In the aftermath of the battle, the U.S. Christian Commission—an organization founded in 1861 by the YMCA and dedicated to caring for the spiritual and physical needs of Union soldiers—called for civilian volunteers to go to Gettysburg to nurse the sick and wounded back to health and to care for those who were dying.

Many women heeded the call, including a number of ladies from Baltimore, among whom was a young, "energetic" woman named Sarah Hutchins. Within days of the battle, Sarah found herself at a field hospital nursing a wounded young Confederate soldier from the 1st Maryland Battalion. Pvt. Leonard W. Ives had been shot on July 3 and lay dying. As Hutchins comforted the dying man, Ives's brother, William, entered the room. William Ives had hurried down from New York City, and when he saw Sarah caring for his brother, he felt a deep sense of gratitude. When Private Ives died on July 14, William knew this was a moment he would never forget.

Sarah Hutchins Sends William Ives Shopping

In December 1863—six months after the battle—William Ives and his wife traveled to Baltimore to visit Sarah. At the Hutchins home they met Sarah's husband, Thomas Talbott Hutchins, a 34-year-old lawyer. Hutchins was a man on the rise in Baltimore. By the age of 24, he had been elected as a Democrat to the Maryland legislature, and he was known in the city as "an affable gentleman, social in disposition" and "an able and eloquent advocate of conservative Democratic principles."

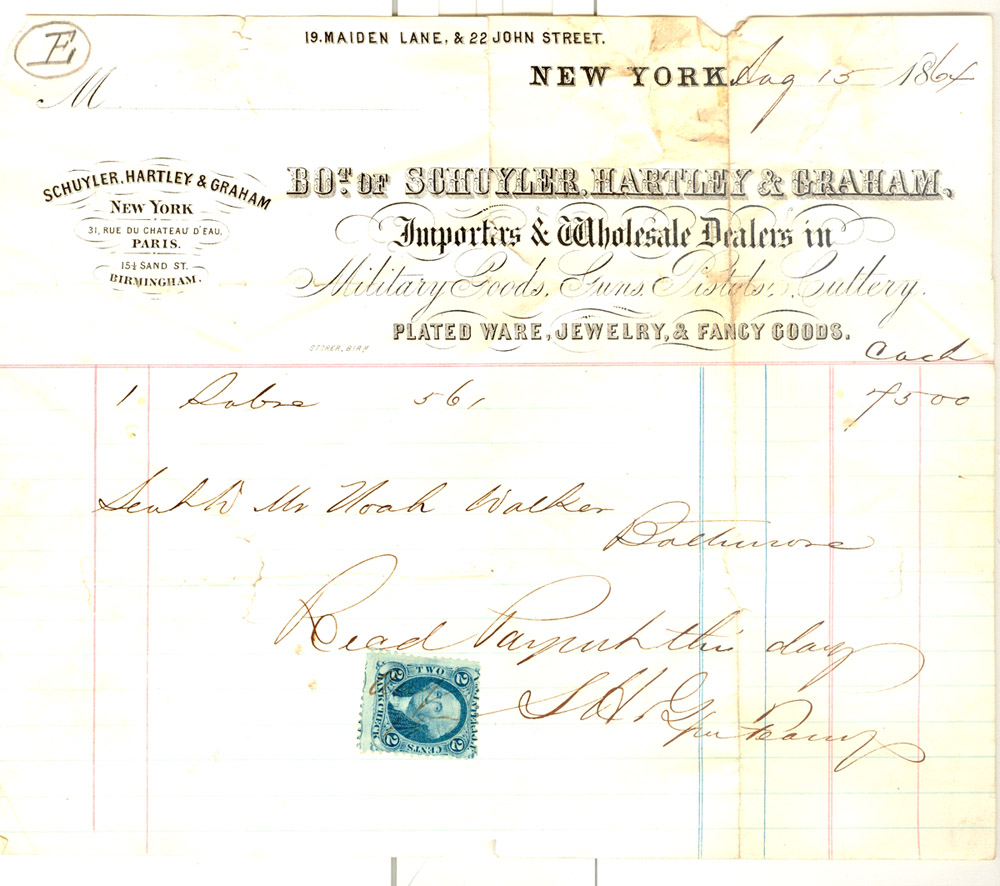

As Ives and his wife were preparing to leave, Sarah made a special request. She told William that she "desired to make a present to a young friend." She did not say who the friend was or where he lived. She simply stated that she wanted to buy him a sword. The problem, as William later testified, was "that the supply was so limited in the city of Baltimore that she could not obtain . . . an article sufficiently elegant," so she asked him to see what he could buy in New York.

Ives returned home and went shopping. He went to Tiffany's and to all of the shops on Broadway. He researched the quality of the various designs and weighed the benefits and detractions of each. A few days later, he sent Hutchins a detailed letter about the various swords she could buy. Months passed, and Sarah never answered.

Finally, in August 1864, Sarah Hutchins was ready to act. She renewed her correspondence with Ives and let him know she was ready to purchase a sword. Over the ensuing month, the two corresponded several times.

In one letter, Ives revealed his antiwar views when he commented on the celebrations in New York City after the fall of Atlanta.

"The flags and rags are flying in all directions this morning," he wrote caustically—and incredulously—on September 3. "My impression is when the full truth is known, the flags & rags will all be taken in again."

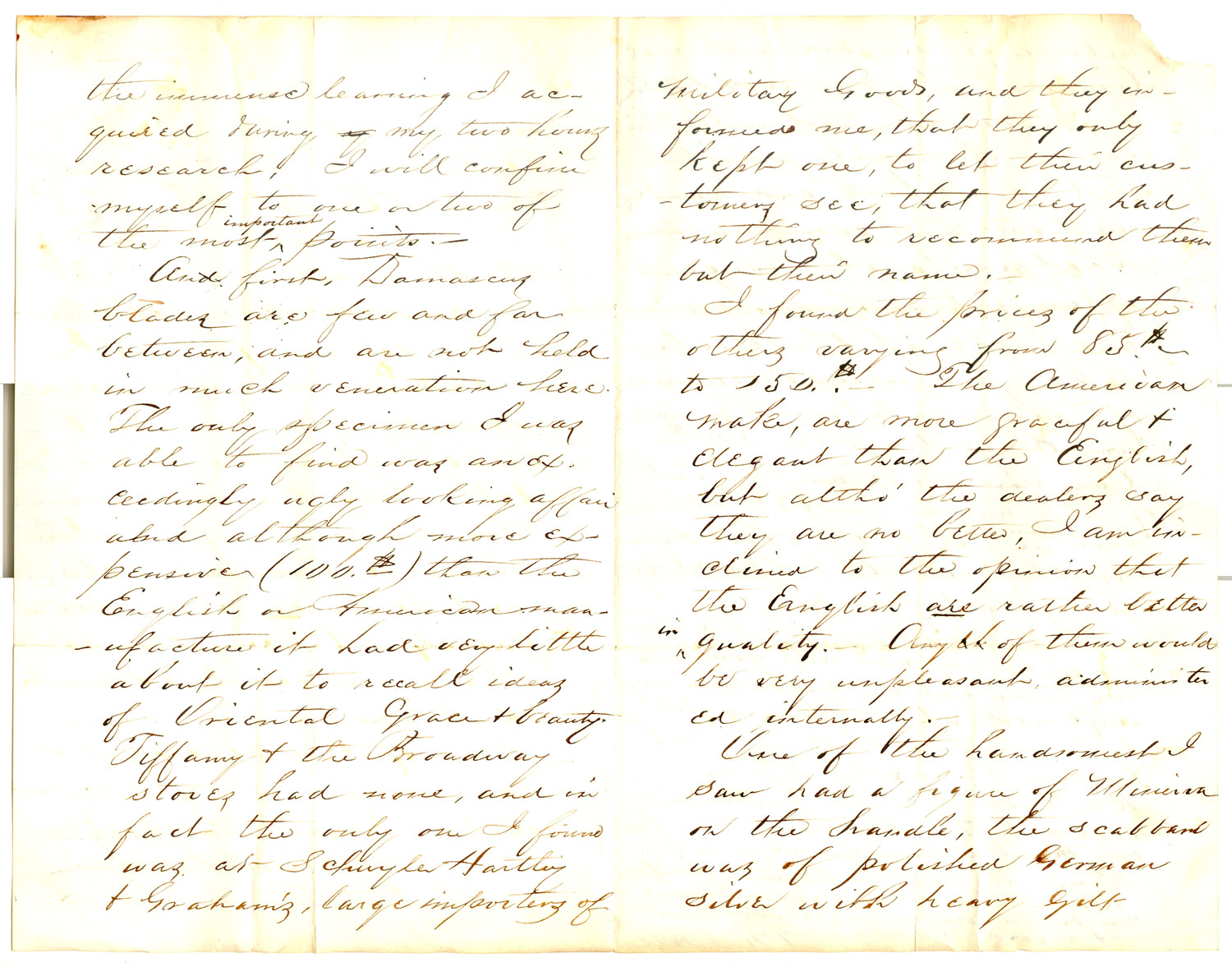

On August 15, Ives went to the store of Schuyler, Hartley & Graham, arms dealers on Maiden Lane (now owned by the U.S. Fire-Arms Manufacturing Co. in Hartford, Connecticut), and purchased a sword for 75 dollars.

Ives followed Sarah's instructions and sent the sword to the home of Noah Walker, a clothing merchant in Baltimore. From there it was transported to the home of Frederick Bernal, the British consul in Baltimore. Bernal was a man of known Southern sympathies, but his official status made his home a safe haven for contraband goods. Sarah rightly believed the sword would be "perfectly safe" there because "Bernal's house would not be inspected" by the federal military.

Sarah Seeks to Honor a Dashing Cavalryman

Ives still had no idea for whom the sword was intended. He had simply acted out of gratitude to help a lady who had shown kindness to his dying brother. But Sarah wanted the sword for a dashing young cavalryman from Baltimore.

Cavalry raiders frequently achieved something of celebrity status during the Civil War. Their daring exploits became the subjects of ballads and songs; their heroic deeds were the stuff of legend. Indeed, the actions of J.E.B. Stuart, John Hunt Morgan, John Singleton Mosby, George Armstrong Custer, Phil Sheridan, and many others remain well known today. In Civil War Maryland, Confederate cavalry officer Harry Gilmor shared nearly the same legendary status.

Born in 1838 in Baltimore, Gilmor was a child of affluence. During the secession crisis, he served in a Maryland state militia unit, the Baltimore County Horse Guards. Once the war began, Gilmor went to Virginia to fight in the rebel cavalry. He spent much of the war as a guerrilla fighter in Virginia, West Virginia, and Maryland. He was known for making daring raids. He captured innumerable Federal soldiers and supplies, several railroad cars, valuable information, and in July 1864 he had Baltimore panicked with rumors that he would sack the Monumental City.

Gilmor was wounded four times, was twice arrested by the Federals, was court-martialed (and acquitted) by the Confederates, and throughout the war rose from the rank of private to colonel because of his military prowess.

Cavalrymen like Gilmor could have a powerful effect on the women back at home. With their strong presence, their charming demeanor, their handsome looks, and their legendary daring, these men on horseback resembled the knights of old. Indeed, one Union soldier referred to Gilmor as "the beau ideal of [the] 'blue blood' ladies" of Baltimore. This was the man Sarah Hutchins sought to honor with a sword.

Unknown to most observers at the time, Sarah also had a familial connection to Gilmor. Sarah's mother had been adopted by a member of the Gilmor family in the 1830s; Sarah and Harry were thus second cousins by adoption.

Sarah Plots to Deliver a Sword to Her Hero

On November 2, 1864, Sarah Hutchins called a poor, almost illiterate black man named Joseph Baker to her home. She had a job for him. Baker had previously done odd jobs for her on several occasions. Following the Battle of Gettysburg, she had paid him to bring the bodies of four dead rebel soldiers to Baltimore. She once also paid him to send "two negroes from the Rebel army" through the military lines and back into the South. Instead, Baker took them to a Union recruiting station.

"I took them away & Enlisted them in the United States Army," Baker boasted, "& then told Mrs. Hutchins that I had put them all Right."

Sarah knew nothing of Baker's schemes, and she now sought his help for a very special mission. She offered him 10 dollars to carry four letters and the decorative sword into Virginia.

The next day, both Hutchins and Baker prepared for the secret mission. Baker went to the office of the Union provost marshal, where he procured a pass to cross the military line into Virginia. Baker had an alias put on the pass. With a fraudulent pass, it would be harder for Union authorities to follow his tracks.

Meanwhile, Hutchins took a stroll to Augusta Bernal's house at 88 Franklin Street. Bernal gave Sarah the sword, and Sarah tucked it under her dress. The two women, joined by a third—perhaps Sarah's daughter—then walked back to the Hutchins home. "I enjoyed our walk yesterday," Augusta told Sarah. "How little our friend dreampt of the weapon you carried or she might have been proud."

Union authorities later believed that "by walking close to Mrs. Hutchins" the two companions "protected her from suspicion & enabled her to hold on to the sabre which she undoubtedly carried under her dress without anyone being able to detect that one of her hands was engaged." When Sarah got home, she hid the sword in a wardrobe.

Joseph Baker returned to the Hutchins home at 132 Park Street that evening. He showed Sarah the pass he had procured, and "she smiled" when she saw it. "Mrs. Hutchins admired my good judgment in having a wrong name put in my pass," he later recalled.

Baker waited patiently as Hutchins sat down to write a few letters. The first was a letter of introduction to a Mrs. Eglandy at Duffield's Station, a small railroad depot in West Virginia, near Shepherdstown. Baker was to present this note to Mrs. Eglandy, and she in turn would point him in Gilmor's direction.

At one point, Thomas Hutchins walked into the room and "asked what was the matter." Sarah quickly changed the topic of conversation. She had called Baker to the house "to fix some flowers &c in the Cemetery," she nervously told her husband. Standing off to the side, Baker believed that Thomas was completely unaware "of what his wife is guilty of."

Once Thomas left the room Sarah went back to her writing. She finished the letter to Mrs. Eglandy and signed it. She then wrote out a sentimental note to Gilmor:

Dear Harry

I hope you will receive this with our love, the bearer will inform you concerning it. You can judge him by his deeds, he is true. We have been very unhappy about your wounds, but hear you are better. All are well and hopeful. The Boys are well. The ——— will return, send us a letter by him.

This is a token of our appreciation for your noble deeds & daring bravery. Accept it with the heartfelt anxiety & regard of Your

Sarah did not sign this letter—she would not risk putting her name on a piece of correspondence to a rebel soldier. She then walked to her wardrobe and pulled out the saber. She handed the sword and letters to Baker and told him "to tear up the letter that had her name on [it]" if he was caught by Union troops. She also gave Baker two letters that a Baltimore neighbor wanted delivered to several kin in the South. She told Baker to look for Mrs. Eglandy at Duffield's Station and from there to find Gilmor. Hutchins handed Baker 10 dollars for his troubles and sent him on his way.

Sarah Hutchins never suspected the cunning of her courier. She believed he was "true," but she would soon find out otherwise.

When Baker had gone to the Union provost marshal's office earlier in the day, he had revealed Hutchins's plan to the authorities. The provost marshal purposely gave Baker the forged pass and arranged to arrest him at Camden Station as he prepared to board the B&O train toward Washington. That night, as Baker approached the train, he was arrested. Taken to the provost marshal's office, Baker gave a sworn statement of Sarah's plot.

The Search Begins for the Elusive Gilmor

Lt. Col. John Woolley, the federal provost marshal in Baltimore, now had some valuable information at his disposal. Woolley dispatched his head detective, Lt. Henry Bascom Smith of the Fifth New York Heavy Artillery, to Duffield's Station to search for Gilmor.

Woolley hoped that Smith would be able to find and arrest the rebel cavalryman. He also thought he might "learn something of the Route by which contraband trade & correspondence is carried on between the Rebels in the City [of Baltimore] & those in Virginia."

In his 1911 memoir, Smith described how he took the train to Duffield's Station and found Mrs. Eglandy's home. Duffield's Station was teeming with Confederate sympathizers, and Smith worried that he and his men would be noticed by local civilians.

"Duffield was a small way station, and any stranger alighting there, especially in those days, would be noted. . . . To give no chance for warning [to local rebel sympathizers], we waited until just after the train started up, and then we dropped off, on the far side, covering view of us until the train was again under headway."

Smith then separated from his men, "and I went ahead, across fields, until I was so far away as to apparently have no connection with my men, who were following." From the station, they walked three or four miles to the Eglandy home.

Upon arriving, Lieutenant Smith went to the door while his men hid in the distance. When Mrs. Eglandy opened the door, Smith produced Sarah's letter of introduction, and he identified himself as a "hack driver at Barnum's Hotel." Mrs. Eglandy read the note, which stated, "The bearer of this is a friend, an exception—do for our sakes take him under your wing and advise him as he is executing an important & responsible duty."

Smith relayed his mission to his hostess: He had a sword that he wished to deliver to Harry Gilmor. Mrs. Eglandy told Smith that Gilmor had been in the vicinity recently, but that he had since gone down the Shenandoah Valley. They then sat down for supper.

"They treated me very nicely," Smith later recalled, and "prepared a good meal for me with true Virginia hospitality."

When Smith left the house, he found his comrades "extremely anxious to get away from that section." A local Confederate sympathizer had happened upon them while they had been hiding and asked if they were "deserters from the Yanks." The soldiers lied and said that they were, so the rebel offered to help them escape further south. The rebel "told them that some of Mosby's men were just over on the road." This made the Federal soldiers even more nervous.

"My boys were not really hungry to go South," Smith recalled, "but wanted to start across the country for Harper's Ferry without delay." Smith and his men made it to Halltown, West Virginia, where, much to their relief, they were captured by Federal pickets. The men had learned Gilmor's whereabouts, but they had been unable to capture him.

Sarah Is Arrested, Interrogated, Jailed

On Monday, November 7, Provost Marshal Woolley ordered the arrest of Sarah Hutchins. His officers, under the command of Lieutenant Smith, searched her home and found correspondence from William Ives and a receipt for the purchase of the sword. They also found letters from Confederate prisoners of war who were being held in Northern prison camps. Woolley believed that these letters showed "that she has an extensive correspondence with them & that her whole heart & soul is enlisted in their behalf." In fact, Sarah's correspondence with some of the POWs led Woolley to conclude that she "is a whole 'Ladies Aid Society' of herself & the tenacity she exhibits in trying to effect exchanges is only another evidence of the devotion of woman when the heart is enlisted."

Fifty years after the war, in his memoirs, Smith recalled the arrest of Sarah Hutchins: "She resided in the ultra fashionable neighborhood, not far from Monument Square. After I had searched her house, she accompanied me to the sidewalk, but absolutely refused to enter my carriage. I informed her that it would be much more agreeable to ride than to walk, but still she refused. I then told her that I would be gentlemanly if allowed, but I insisted that she must get into the carriage. She finally complied."

Smith brought Hutchins to the provost marshal's headquarters and took her upstairs to his office. After a short while, Woolley came in to question Sarah. At the trial he testified: "I asked Mrs. Hutchins in regard to two letters that were taken from this man Baker, one of which was addressed to Mrs. Eglandy and she acknowledged to me during the interview I had with her that she wrote those letters. . . . I stated to her I knew all about this sabre, that it was intended by her for Harry Gilmor, and that it came from her house and that I knew she wrote the letter."

Sarah initially lied and said that she had not written the letter, but she quickly changed her story. She "acknowledged to the writing of the letter and acknowledged that the sabre was for Harry Gilmor," Woolley stated. She also confessed that she had contributed one dollar toward the purchase of the sword. Sarah then begged Woolley to release her "upon her taking the oath of allegiance." She cried she "would do anything to get out of this."

After the interrogation, Woolley sent her to the Baltimore City Jail. About a week before Sarah's arrest, the warden had arranged with the U.S. military to provide Federal prisoners with "good, wholesome and sufficient cooked food for their proper maintenance and comfort" and to give them "good and comfortable quarters." But Hutchins apparently did not fare well at the prison.

On November 10, 1864, Dr. J. F. Powell wrote to the military commander at Baltimore: "Mrs. Hutchins, a prisoner in the city jail is suffering from the change in her mode of living and the excitement caused by her arrest. . . . I believe she would be benefited by permitting her friends to furnish her one meal a day."

With Hutchins securely imprisoned in Baltimore, Woolley decided to widen his dragnet. He telegraphed Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler in New York City to arrest William Ives, and he ordered the arrest of Baltimore merchant Noah Walker. He also contemplated arresting Augusta Bernal, the wife of the British consul. Meanwhile, on the very next day—November 8, 1864—Abraham Lincoln was reelected President of the United States. Much of the nation breathed a sigh of relief, while many Southerners believed the election was a significant nail in the coffin of the Confederacy.

Sarah Goes on Trial Before a Military Tribunal

Sitting in the Baltimore City Jail, Sarah Hutchins had little time to reflect on the gravity of her actions. Within a week she was arraigned before a military tribunal. On Sunday, November 13, she learned the charges against her. The trial began the next day. Her prosecutor (called a judge advocate) was a cavalry officer from Delaware. The tribunal consisted of eight military officers from various Northern states.

She faced three charges: 1. "Holding unauthorized intercourse with the enemies of the United States in a place under martial law"; 2. "Violating the laws of war as laid down in paragraph 86 of the General Order No. 100, from the War Department April 24, 1863" (which prohibited "all intercourse between the territories occupied by belligerent armies, whether by traffic, by letter, by travel, or in any other way"); and 3. "Treason under the laws of war."

These were grave and infamous charges. Hutchins procured the services of two noted Baltimore attorneys, William Schley and Jonathan Meredith.

Schley was a 65-year-old attorney from Frederick, Maryland, who had mentored Thomas Hutchins in the 1850s. During the Civil War, Schley took several cases in which he defended Union military officers when they were sued by "disloyal" Maryland civilians for wrongful arrest.

Meredith was one of the most distinguished members of the Baltimore bar. At 81, he had grown up in Philadelphia and had memories of sitting behind President George Washington in church in the 1790s. Meredith was very near retirement, but he likely agreed to take Hutchins's case because he had known her family for many years.

As the trial opened, Hutchins's attorneys immediately asked for more time to prepare for the case. The judge advocate replied that "the Accused and her counsel had enjoyed as much time as himself in the preparation of the case and he therefore objected to any postponement." The military commission agreed with the judge advocate and ordered the case to proceed.

The first witness called by the prosecution was none other than Joseph Baker, the African American courier who had betrayed Hutchins to the authorities. Hutchins immediately "objected to the competency of this witness." Under Maryland law, her lawyers argued, "a colored person is not a competent witness in any case, against a white person, much less in a case where one of the allegations, charged against the accused, is treason and where the punishment of treason may be inflicted." And any court sitting in Maryland was bound to follow local law and custom, they claimed. Allowing Baker to testify "would set the precedent."

The judge advocate replied that in military courts throughout the nation, African Americans "were now universally admitted . . . as competent witnesses." The commission agreed and decided to allow him to testify. Baker provided damning testimony of Sarah's actions, recounting all of their interactions.

Provost Marshal Woolley also testified that Hutchins had contributed one dollar toward the purchase of the sword. The defense chose not to cross-examine him, and the prosecution rested its case. Hutchins and her lawyers then asked for more time to prepare their case. The court adjourned until noon the next day.

What Is Meant by "Treason Under the Laws of War"?

Hutchins's attorneys prepared a learned legal defense, which she read to the court when it reconvened on November 15. She essentially admitted to all she was accused of doing, but she maintained that the charges against her were defective and illegal and that a military court could not have jurisdiction over a civilian when and where the civil courts were open.

Hutchins made several important legal points. First, she claimed that she had not been in contact with Gilmor because she had not delivered the sword and letters to him. "At the utmost, it was an attempt, in pursuance of a purpose, to send the letter and sword; and may be properly characterized as an attempt to hold intercourse; but no intercourse was, in fact, held; because the attempt was frustrated."

Using the crime of murder as a metaphor, she pointed out that "homicide means an actual killing, not a mere ineffectual attempt to kill." Thus, she claimed that she had been charged with the wrong crime; even if a treasonable intention could be proved, she claimed that she had committed no overt act.

Second, she argued that the charge of "Treason under the laws of war" was not a proper charge for a U.S. citizen. Treason is the only crime defined in the Constitution. Article III, section 3, states: Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort. No Person shall be convicted of Treason unless on the Testimony of two Witnesses to the same overt Act, or on Confession in open Court.

The requirement for an "overt Act" precluded judges or politicians from declaring that conspiracy, words, or thoughts might be deemed treason, and the requirement for two witnesses or a confession in open court sought to prevent convictions based on false testimony by a single witness. In defining treason narrowly, the Founding Fathers hoped to depoliticize a crime that for centuries had been partisan in nature.

Hutchins claimed that if she was charged with treason, she must be charged according to the constitutional definition. "Now what is meant by 'Treason under the laws of war'?" she asked rhetorically.

This was a wholly new and unprecedented concept in American law. But even if she was charged with treason "under the laws of war" rather than under the Constitution, she maintained, she must be charged with an overt act of treason. And as she had already attempted to demonstrate, she had not actually accomplished any treasonous act. Moreover, each witness had testified to different actions—none of them gave corroborating evidence of the same act of treason.

"The proof, that I contributed money to buy the sword, is found, only, in the evidence of Col. Woolley, who says that I acknowledged that I had contributed one dollar, towards the purchase of the sword," stated Hutchins in her defense. "No other testimony is offered on this point; & even viewed as a confession, on my part, of the overt act of contributing one dollar towards the purchase of the sword, it is not a confession in open court; & the law is well settled, that the confession of the accused, out of court, is not sufficient to dispense with the required proof of two witnesses to the same overt act, . . . [or] a confession in open court."

Finally, Hutchins claimed that a military commission was not the proper venue for her trial. The Constitution requires that treason trials, like all criminal trials, must be civil proceedings.

"The trial of all Crimes, except in cases of Impeachment, shall be by Jury," states Article III, "and such Trial shall be held in the State where the said Crimes shall have been committed." The Fifth Amendment further requires: "No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger."

Accordingly, members of the military may be tried by military courts, but civilians must be tried in civil courts. Finally, the Sixth Amendment states: "In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed."

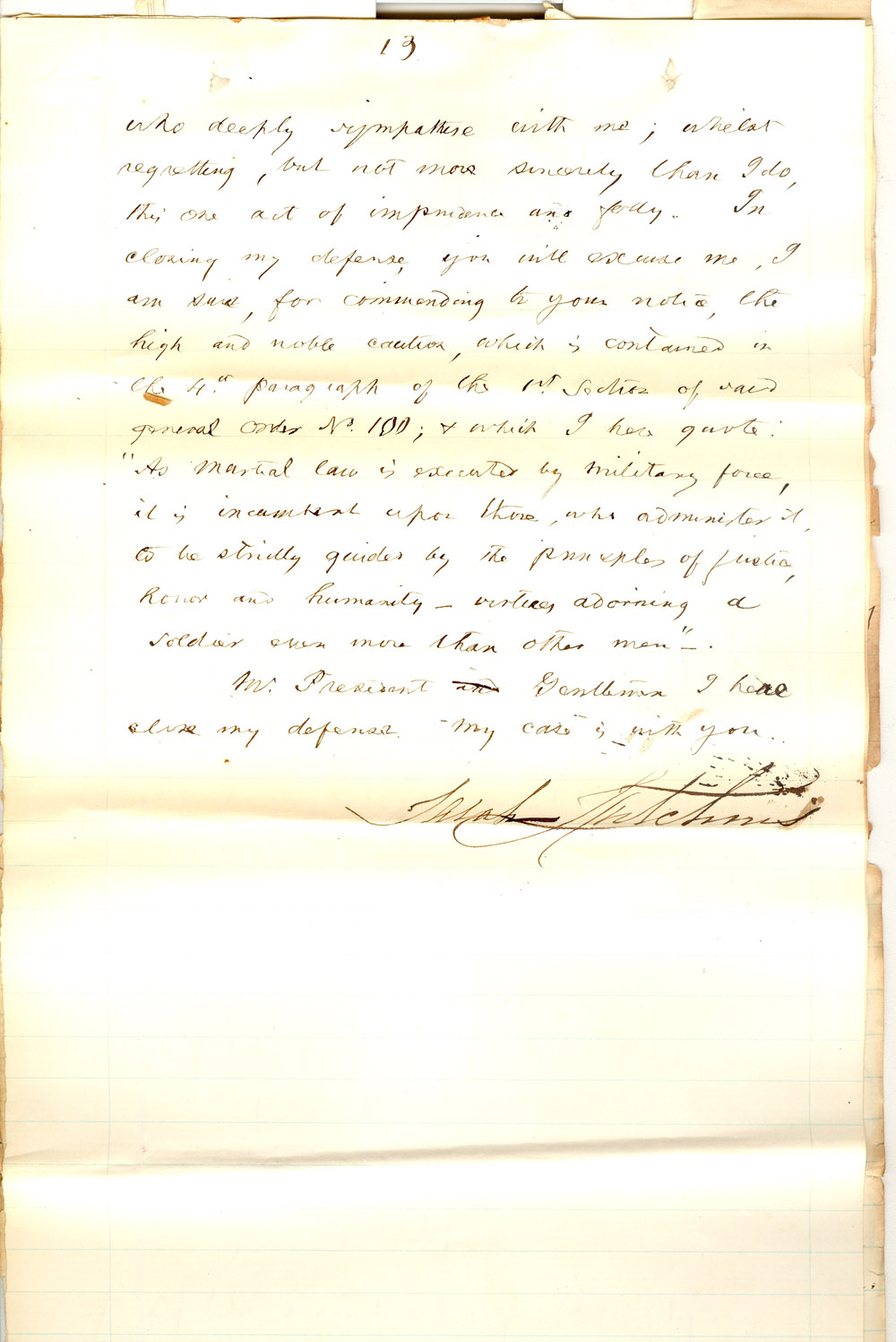

Hutchins closed her defense by quoting from the Articles of War to remind the military court of its own governing principles: "As martial law is executed by military force, it is incumbent upon those, who administer it, to be strictly guided by the principles of justice, honor and humanity—virtues adorning a soldier even more than other men."

She admitted to having committed an "act of imprudence and folly," but she denied that she had committed treason. She asked for mercy on behalf of her children, her husband, her widowed mother, her "suffering Aunt," and "the many near and dear friends who deeply sympathize with me." There she rested her case.

The court adjourned to deliberate, but it quickly arrived at a verdict: She was found guilty of all charges and was sentenced to imprisonment for five years at labor and a $5,000 fine. Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace, the military commander at Baltimore (and later author of Ben Hur), ordered her sent to Fitchburg Prison in Massachusetts. According to the Boston Journal, she "bore her imprisonment in a remarkably quiet manner, and was evidently determined to make the best of her situation."

Newspapers throughout the North reported on Hutchins's trial and sentence. Some roundly praised the verdict, while others called for clemency. In western Maryland, a Union League club unanimously adopted a resolution "expressing their satisfaction" with the outcome of the trial, which they sent to General Wallace.

"We can assure you that even the Southern sympathizers in this vicinity cannot find arguments with which to vindicate the conduct of so traitorous and disloyal a person as she has proved herself to be," they told the general. "Copperheads [antiwar Democrats] here acknowledge the decision as just & merited."

Another Trial, Another Verdict

On November 9, William Ives was arrested at New York City and brought to Baltimore for trial. Like Hutchins, Ives was tried before a military commission. He, too, was charged with "violation of the laws of war" and "treason under the laws of war" for working with Hutchins to procure the sword for Gilmor. Like Hutchins, Ives pleaded not guilty.

Ives's trial sat for four days. Ives asked for permission to take Hutchins's testimony in a deposition, but the court refused. In a moment of great irony, the judge advocate argued that "Mrs. Hutchins was tried and convicted of an infamous crime and her testimony was not admissible." The members of the military commission agreed. A black man could testify, but a traitor could not.

The only testimony against Ives came from Provost Marshal Woolley, who briefly recounted how Ives's correspondence had been seized at Sarah Hutchins's home. Ives then called a number of witnesses—including Thomas Hutchins—who established that Ives was loyal, although he was a Peace Democrat. Witnesses testified that Ives barely knew Sarah, that he did not know the sword was for Gilmor and only bought it for Sarah out of gratitude to her for comforting his dying brother, and that he was innocent of any treasonable actions or intent.

On December 5, Ives's attorneys made two long statements. They, too, challenged the jurisdiction of the military tribunal, and they argued strenuously that Ives had no intimate relations with Hutchins or any other rebel sympathizers in Baltimore. On December 6, the commission found Ives "not guilty." Five days later, General Wallace ordered his release from prison.

Things quickly took a turn for the better for Sarah Hutchins. In late December, President Lincoln pardoned her, and the War Department informed the warden at Fitchburg Prison that she was to be released "upon making acknowledgement of her wrong and giving her parole of good behavior."

The Central Press of Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, reported that she "made a statement previous to her release, acknowledging the wrongfulness of her conduct, the justness of her sentence, and affirming her determination to hereafter conduct herself in a loyal manner." On New Year's Eve she walked out of prison a free woman.

Some observers doubted that Hutchins really felt remorse for her actions. William Wilkins Glenn, a Maryland journalist with Southern sympathies, made several caustic observations in his diary.

"As soon as she was arrested, she broke down utterly. She went on her knees and offered to sign any parole or take any oath that was required. She urged that she was 'enceinte,' which was not so, and on her return from prison while at New York made a joke of having used this pretense in order to obtain her release."

But more importantly, Glenn blamed Hutchins for "so foolishly" endangering Marylanders "who were really serving the South." Attempting to send a sword to Gilmor "and to be so foolish as to entrust it to a negro, who, she might be sure would betray her, was so very silly as to disarm suspicion." Hutchins's actions following her release also struck Glenn as bizarre. When she returned to Baltimore, she apparently invited her jailor to dinner. A bemused Glenn wondered in his diary: "I would like to know if she allowed him to make love to her while she was in jail."

As the war came to a close in the spring of 1865, the Hutchins case faded out of the public memory. Once the dust had settled, Wallace presented the infamous sword to Lieutenant Smith.

Gilmor Finally Captured, Later Seeks the Sword

On the cold, snowy morning of Sunday, February 5, 1865, Federal officers under Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan captured Harry Gilmor as he slept in a home near Moorefield, West Virginia. Gilmor was brought through his hometown of Baltimore on his way to prison at Fort Warren in Boston Harbor.

While at the provost marshal's office, Gilmor and Lieutenant Smith finally met face to face. Gilmor did not record the meeting in his memoir, but Smith did. "Gilmor said to me, if he had had the sword, he would have killed many a Yank with it. A safe enough proposition under the circumstances." Smith recalled his first impression of the rebel hero: "Gilmor in appearance was attractive, as a soldier, tall, fairly stout, but he had one defective eye and was rather course in manners."

Gilmor was held in a casemate at Fort Warren until July 24, 1865, when President Andrew Johnson ordered the release of lower ranking Confederate officers. Gilmor was indicted for high treason in the federal court in Baltimore, but the charges were dismissed in November 1866. That same year he published his celebrated memoir, Four Years in the Saddle.

In 1873 the governor of Maryland appointed Gilmor a cavalry officer in the Maryland National Guard. His memory hearkened back to that sword he had never received in 1864. Using several connections, Gilmor acquired Smith's address in New York City and sent his old antagonist a letter:

"My object in writing is to know whether or not you still have in your possession the sword which the ladies of Baltimore intended for me, but which fell into your hands. If you have the sword still, and would be willing to dispose of it, will you say what you will take for it, as I would like very much to own it, if it did not cost too much." Gilmor explained that he had recently been "elected to the Command of a Battalion of Cavalry in this city, composed of men who were on both sides during the 'late unpleasantness,' and am very anxious to make a fine battalion of it."

Smith mulled over Gilmor's request. "At that time," recalled Smith, "everything was being done to 'heal the wound' and I was disposed to do my little part. I was disposed to present the sword to him, first getting General Wallace's approval. But on conferring with Union people of Baltimore, I concluded not to; they thought any ostentatious display of the sword would help keep the wound open."

Jonathan W. White is assistant professor of American Studies at Christopher Newport University and author of Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil War: The Trials of John Merryman (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2011). In 2007, he published "'Sweltering with Treason': The Civil War Trials of William Matthew Merrick" in Prologue.

Notes on Sources

Most of the research for this article was conducted at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. The military commission case files of Sarah Hutchins and William Ives are in Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General (Army), Record Group (RG) 153. Correspondence relating to the arrest of Hutchins can be found in Records of the Adjutant General's Office, RG 94, and Records of United States Army Continental Commands, RG 393. Records relating to Gilmor's indictment for treason are in Records of the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Maryland, RG 21, at the National Archives at Philadelphia.

Supplemental information about Harry Gilmor and the Baltimore City Jail is available in several issues of the Maryland Historical Magazine. Thomas Talbott Hutchins's biography in Biographical Cyclopedia of Representative Men of Maryland and [the] District of Columbia (1879) contains the description of him as "an affable gentleman." I also thank Lance Humphries, who has done significant work on Robert Gilmor, Jr., for helping me discern the familial connection between Sarah and Harry.

Several memoirs helped illuminate the story: Harry Gilmor, Four Years in the Saddle (1866); Lew Wallace, Lew Wallace: An Autobiography (1906); and Henry B. Smith, Between the Lines: Secret Service Stories Told Fifty Years After (1911). Some of the recollections in these memoirs conflict with the records held at the National Archives. Most significantly, neither Smith nor Wallace mention the indispensable role of Joseph Baker in the capture of Sarah Hutchins.

Readers interested in the civil liberties issue during the Civil War should consult Mark E. Neely, Jr., The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties (1991) and my own Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil War: The Trials of John Merryman (2011).