The 1961 Berlin Crisis

Some New Insights

Fall 2011, Vol. 43, No. 3

By Neil Carmichael and Brewer Thompson

- See also an examination of the Berlin Crisis in the publications of the 2011 conference "A City Torn Apart: Building the Berlin Wall".

Fifty years ago, talks between the United States and the Soviet Union broke down over the status of Berlin, capital of the defeated Nazi German state.

At the end of World War II, Germany was divided into occupation zones, with each ally—the United States, France, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union—in control of a zone. Berlin was in the Soviet sector, but it was agreed that it, too, would be divided, and the Soviets would allow the other allies access to it.

By the end of the 1950s, however, the Soviets wanted the other allies out of Berlin. They refused, and tensions escalated over the next few years.

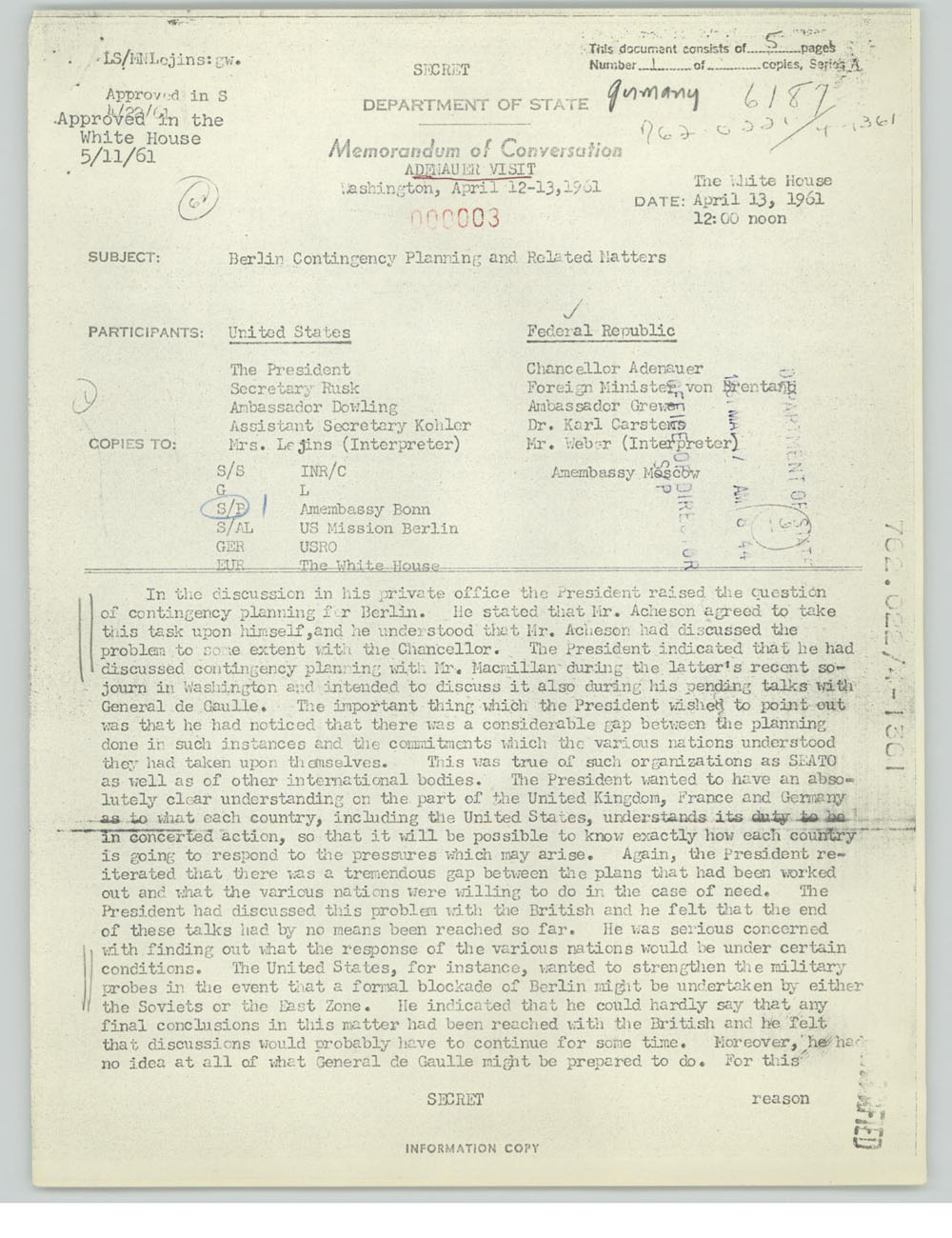

When Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev met the new U.S. President, John F. Kennedy, in Geneva in June 1961, he reiterated his desire for the western allies to leave West Berlin and proposed a peace treaty on Soviet terms. The Western allies, however, had no intention of giving up their right of access to Berlin.

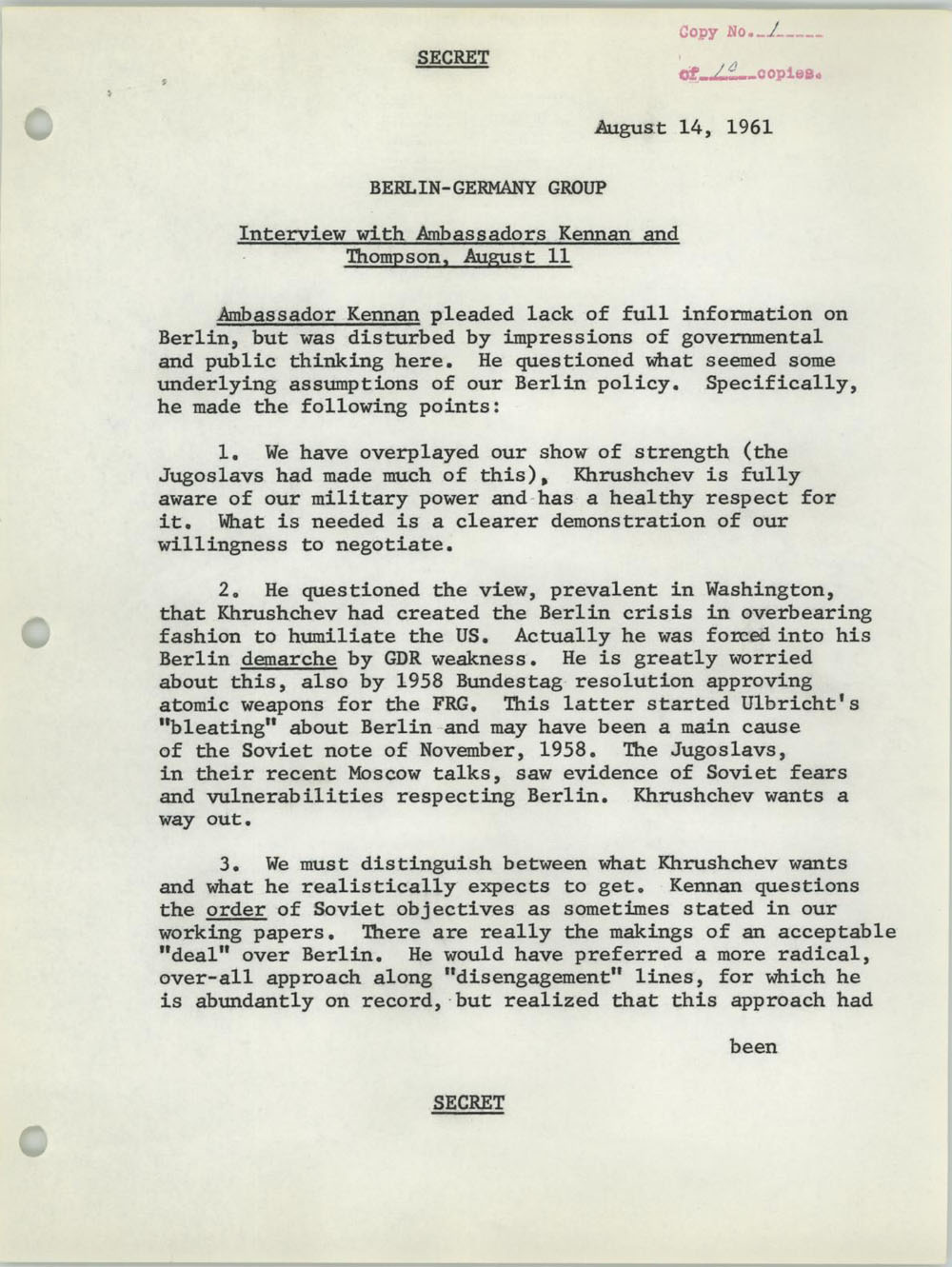

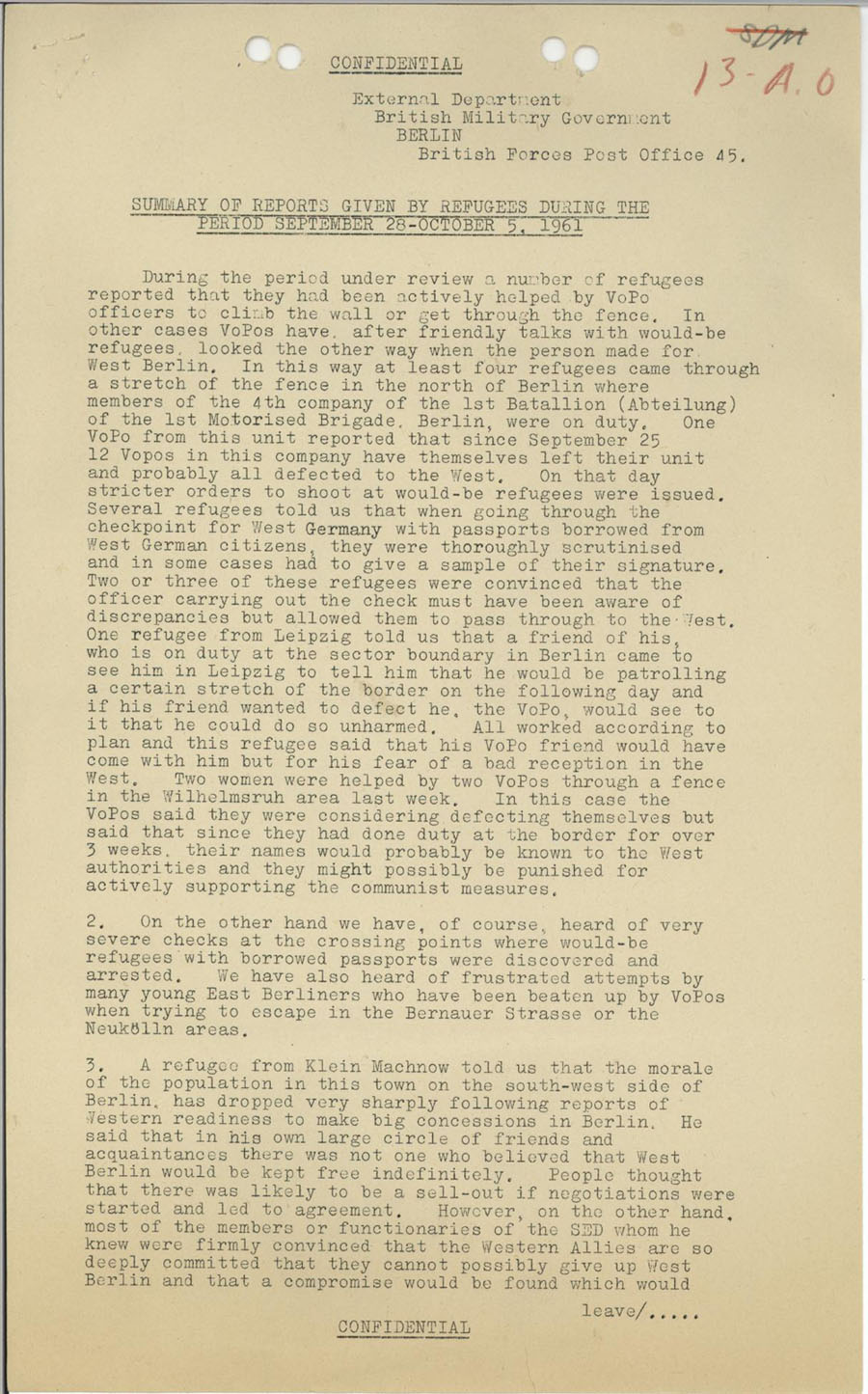

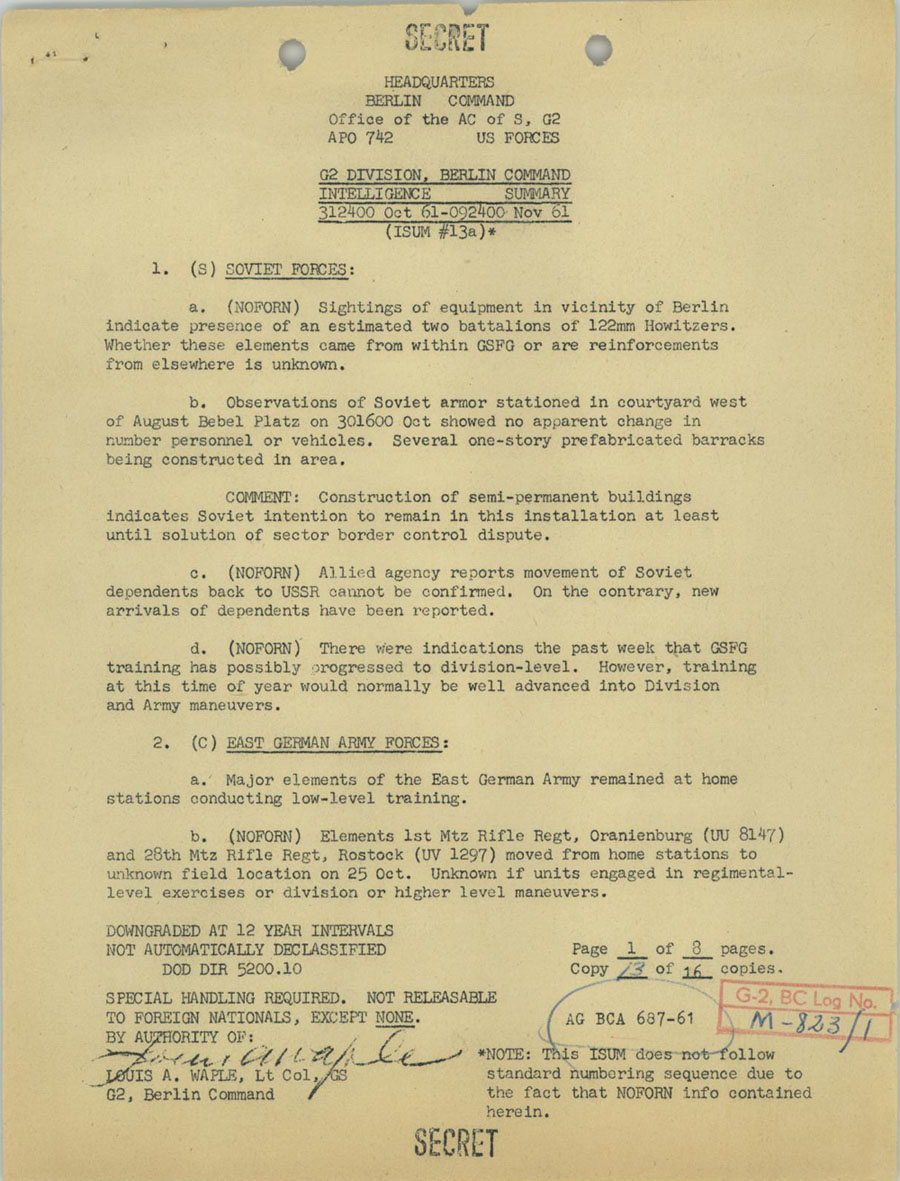

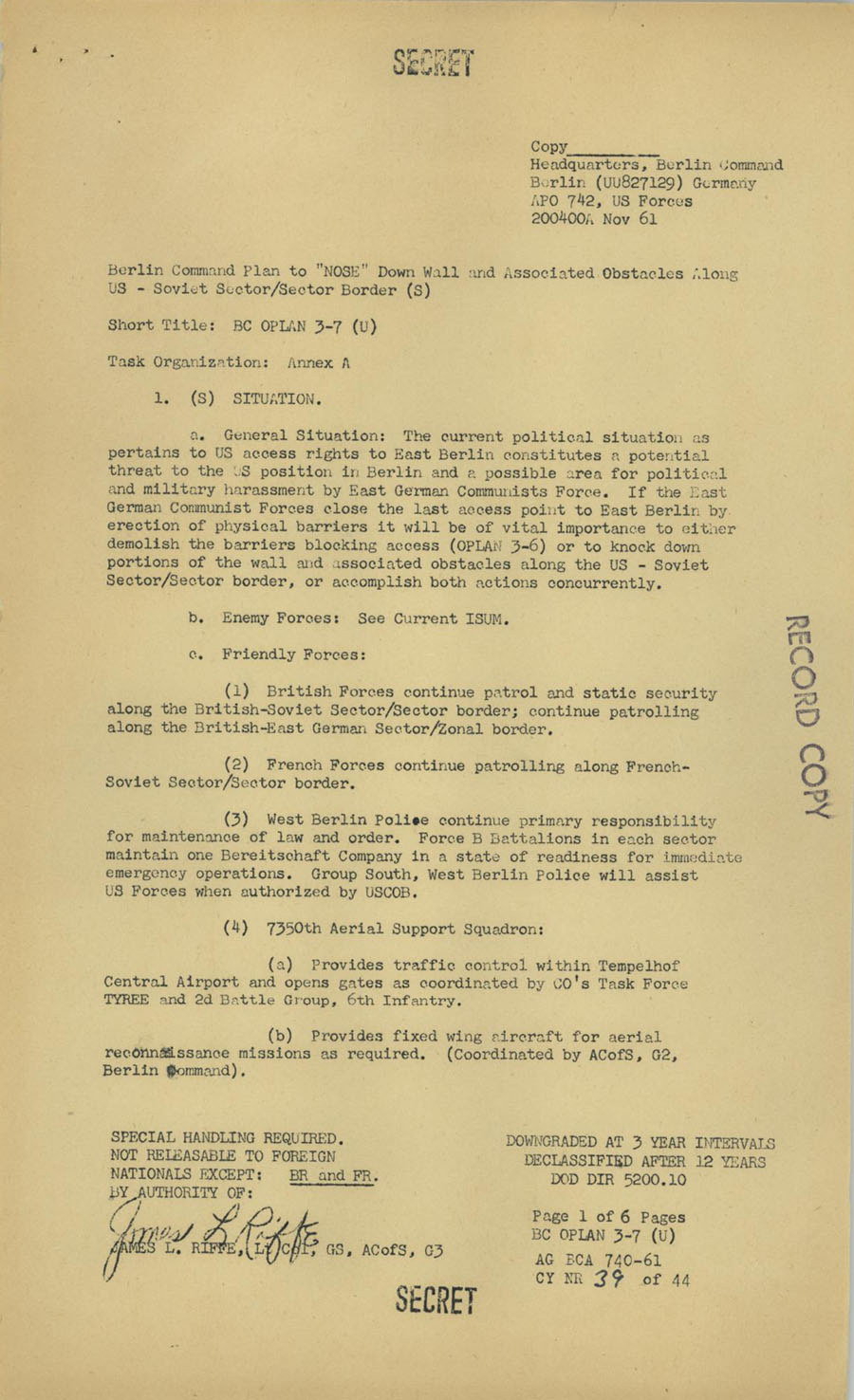

In early August 1961, the Soviet-controlled East Germans began cutting off all avenues of escape to West Berlin—the 97 miles surrounding the city and the 27 miles that cut through the heart of the city. The Soviets and East Germans moved in with a massive show of force, and Kennedy called 148,000 National Guardsmen and Reservists to active duty.

And the East Germans began to build a wall, a tangible symbol of what Winston Churchill had called the "iron curtain" dividing Soviet-controlled Eastern Europe and Western Europe.

Once the wall was up, the access checkpoints became points of contention. On October 27, 1961, the Soviets deployed 10 tanks on their side of Checkpoint Charlie, and U.S. and Soviet tanks stood a mere 100 yards apart from each other. The confrontation made headlines around the world, and until Moscow and Washington mutually agreed to pull back, it looked as if the Cold War would become hot.

Throughout the summer of 1961, the story unfolded in dozens of reports, meetings, and discussions on an Allied response against a backdrop of possible nuclear war.

Roughly 500 recently declassified documents were published jointly by the National Archives and Records Administration's National Declassification Center and the Central Intelligence Agency's Historical Publications Office and distributed in conjunction with a conference on "A City Torn Apart: Building the Berlin Wall" at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., on October 27, 2011.

The Berlin Wall would stand for another 28 years before the people of East Germany would peacefully rise up and regain their freedom.

More documents can be found in the CIA's Berlin Wall Collection.