“A Reasonable Degree of Promptitude”

Civil War Pension Application Processing, 1861–1885

Spring 2010, Vol. 42, No. 1

By Claire Prechtel-Kluskens

The Civil War wrought monumental changes in many aspects of American life, in both the North and the South, that affect the nation's social, economic, and political character to this day.

The war not only strengthened the federal government, it also made it bigger. One example is the veterans' pension system, which grew from a small government program to one that for the first time affected hundreds of thousands of families.

Before the rebellion, the cumulative number of persons placed on the pension rolls had been relatively small—25,000 Revolutionary and post-Revolutionary veterans and widows. Twenty years after the war's end there were nearly 325,000 veterans, widows, and other dependents on the pension rolls, plus 20,000 War of 1812 veterans and widows.

Researchers recognize the immense value of Civil War pension files for genealogical and historical research, but few are aware of the issues that faced the pension office. The best sources of information are the annual reports of the commissioner of pensions, which were included by the secretary of the interior in his annual report to Congress.

In 1860, the pension office had a stable workload. At the end of the fiscal year, June 30, 1860, 11,284 pensioners on the rolls received an aggregate of just over $1 million a year. Since the workload had not changed much since the previous year, Commissioner George C. Whiting concluded on November 16, 1860, "I am still of the opinion heretofore expressed that the clerical force of the office may soon be somewhat reduced." By 1865, 2,688,523 men served under Union orders, and the pension office grew accordingly. The pension office workforce of 72 in 1859 would mushroom to 1,500 in 1885. Annual pension payment costs of $1 million annually in 1860 ballooned to $36 million in 1885.

The outbreak of armed hostilities on April 12, 1861, resulted in suspension of payments to pensioners living in insurrectionary states, although some remained on the rolls by transferring their names to pension payment agencies in loyal states. Under an act of July 17, 1862, all persons prosecuting claims with the government had to swear an oath of allegiance; this law was still in effect in 1874 when Commissioner J. H. Baker suggested its repeal. The pension office suspended payments to those about whom "credible and responsible information going to prove their active participation or avowed sympathy with the southern insurrection" had been received.

Civil War Pension Laws

Called "the most liberal pension law ever enacted by this government" to that time, the pension act of July 14, 1862 (12 Stat. 566) increased pension rates and provided potential eligibility for pensions to every person in military or naval service since March 4, 1861, their widows and orphans, and for dependent orphan sisters. Indeed, some people feared the law would result in "an extravagant, if not insupportable, annual burden," even though it was "certainly no more liberal than simple justice demands toward the armed defenders of the country in this day of trial." By November 15, 1862, 10,804 applications "on account of the present war" had been received, but only 685 had been granted because the pension process relied upon the Adjutant General's Office and the Navy Department to confirm details of death or disability for each application.

Under pressure from veterans, Congress repeatedly modified pension laws to liberalize eligibility and increase payment rates. Between passage of an act of March 3, 1873 (17 Stat. 566), and June 30, 1874, the pension office reevaluated 30,000 claims of widows and children. An act of March 3, 1883, resulted in nearly 16,000 applications for increased payments by June 30, 1883. The system was complex; in 1873, there were 88 different rates for Army pensions and 58 for Navy pensions. In 1882, there were 117 different grades of pensions.

Minor variations in statutory language led to problems of interpretation. The act of July 14, 1862, provided an $8 a month pension to private soldiers for "total disability" for the performance of manual labor, while the act of June 6, 1866, provided a pension of $20 a month (increased to $24 a month by the act of June 8, 1872) for a disability incapacitating for the performance of "any manual labor." In 1874 Commissioner J. H. Baker explained that the words "total disability" in the 1862 act "have been construed by this Office to mean a total disability for the performance of manual labor requiring severe and continuous exertion" while the words "any manual labor" in the 1866 and 1872 acts "have been construed to include also the lighter kinds of labor which require education and skill." Baker believed that this construction was "in accordance with the intention of their framers; but, as it is difficult to draw a line of distinction between the two kinds of labor, there is to some extent a conflict between the acts referred to, which renders their execution difficult, and the decision of the Office thereunder unsatisfactory to claimants."

Another conundrum was the prohibition against pension payments to "any person who in any manner aided or abetted the rebellion." Some former Confederates had subsequently joined the U.S. Army or Navy but now found themselves unable to obtain a pension for injuries received or disease contracted during their post–Civil War military service. Also, volunteer officers and privates received different pensions based on rank as well as on disability, even though both had "been drawn from and returned to the same walks of civil life." Commissioner W. W. Dudley in 1882 suggested that men who deserted after incurring a disability should not forfeit their right to a pension, which was not granted for meritorious service, but as "payment for loss of physical ability to earn a livelihood." Although fewer in number, claims related to veterans who were Native American, imprisoned, insane, or residing in a National Military Home also posed special problems of various kinds.

Medical Examination

Some veterans returned home with temporary disabilities. Commissioner Joseph H. Barrett noted that "the number of soldiers discharged on a certificate of disability is by no means a measure of the number that are entitled to receive invalid pensions" since disability for military service did not necessarily mean the soldier was disabled from civilian employment. Army and Navy medical officers received no definite instructions on rating the degree of disability of soldiers and seamen to be discharged for injuries or disease. As a result, in a study of 300 veterans consecutively examined by William M. Chamberlain, M.D., 10 percent had no current disability, and the remaining 90 percent had disability ranging from one-fourth to total, averaging about two-thirds disabled.

While the 1862 act did not expressly define disabled, the pension office continued to follow the express language of the act of April 10, 1806 (2 Stat. 376) and the office's established precedents that disability was measured by the veteran's capacity "for procuring a subsistence by manual labor"—not by whether he could perform the particular kind of employment he had before military service.

Loss of limb or its extremity was always rated as a total disability, but other types proved more complex and troublesome to rate. Was the disability permanent or temporary? Incurable or treatable? An organic or functional disease? "Superinduced" by military service or "partly constitutional"? An unavoidable result of climate, exposure, or battle, or from carelessness or self-neglect? (If from carelessness or self-neglect, disability was not pensionable.) These complex questions vexed the commissioner of pensions, who at least three times requested that Congress consider appointing a commission of surgeons to prepare a scale of disabilities or authorize the bureau to have its own supervising surgeon to wrestle with these details. He eventually got his wish.

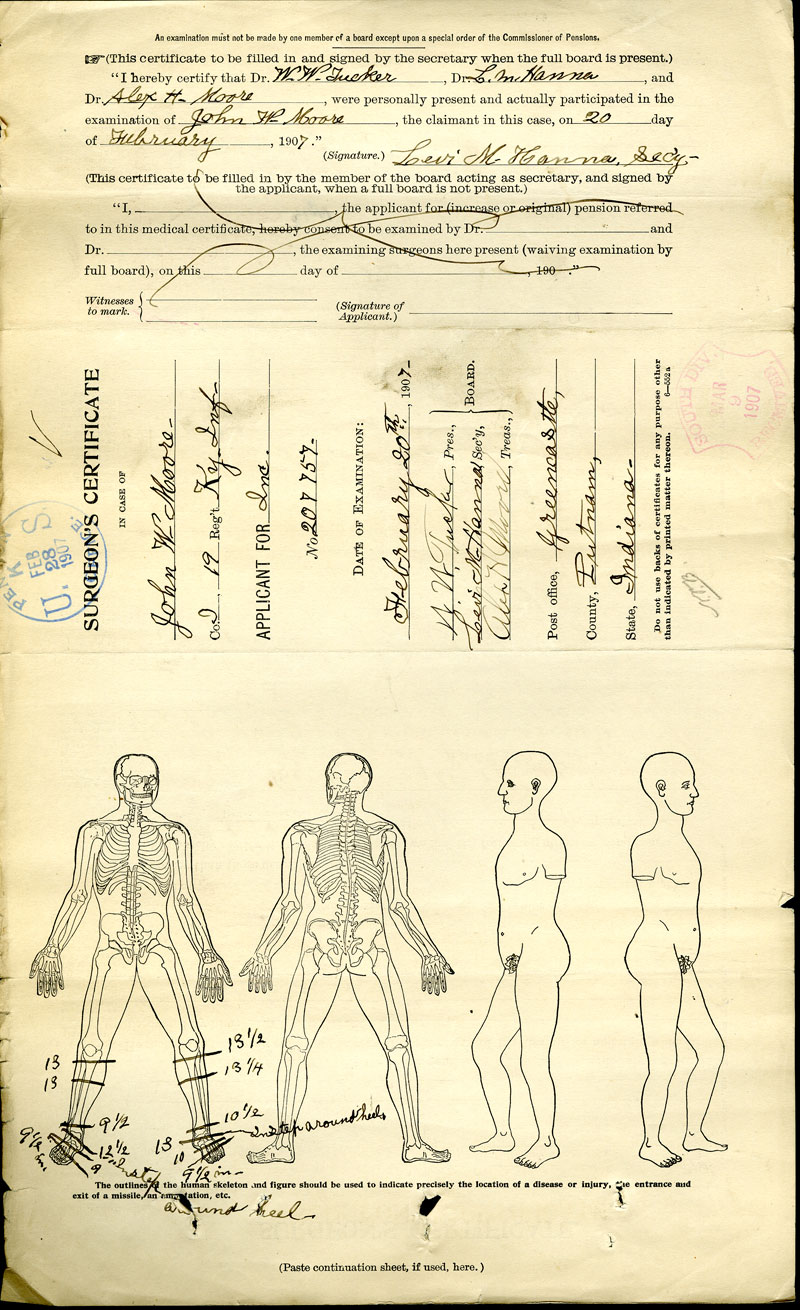

To ensure that veterans receiving pensions remained entitled to them, the act of July 14, 1862, required invalids to submit to physical examination every two years with a physician chosen by the commissioner of pensions. An act of July 4, 1864 (13 Stat. 387), authorized special examinations of enrolled pensioners, "as justice might seem to require," resulting in annual or semiannual examinations of some pensioners "in cases of manifestly temporary and variable disability." Congress left the number and locations of these civilian physicians to the discretion of the commissioner, and 172 civilian doctors were appointed by November 15, 1862, in those places "where the convenience of applicants seemed to require such an officer." As the number of veterans needing examination grew, so did the number of physicians appointed, from 172 in 1862 to 1,578 in 1877. Totally disabled veterans were not required to go to biennial examinations.

Ensuring that competent and scrupulous physicians and surgeons did examinations was an important concern. In most counties, a single physician conducted the examination; in larger cities, boards of three or more physicians were established, with the requirement that at least two of them jointly conduct the examination. In 1882–1883, the pension office changed the system so that a board "of three first-class physicians and surgeons" jointly conducted all examinations. Although the cost of paying three doctors $2 each was greater than paying a single examining doctor, the more accurate results saved the government money. Boards were geographically established so that no claimant was required "to travel over 40 miles to reach one by rail," an important concern since roads were unpaved.

These examinations could sometimes result in reductions in pension payments or complete removal from the pension rolls. In 1865, George S. Jones, M.D., and A. B. Bancroft, M.D., examined 407 pensioners on the Boston pension roll whose payments totaled $29,596 annually. After their examinations, four pensioners were dropped, "a few" received increases, and determinations of decreased disability in many others resulted in savings of $6,520 annually (about 22 percent).

By 1871, the commissioner established a Medical Division "of competent surgeons" within the pension office to "rigidly inspect all returned [examination] certificates and to correct and adjust all medical questions." Efforts to ensure that physicians knew what was required resulted in "increased care in conducting the examinations and in the construction of the certificates of examination" so that, in 1873, only 5 percent had to be returned for correction or greater detail, down from 40 percent two years earlier. But it remained a constant struggle to get medical examinations—arguably the most important part of the claims adjudication process—properly done and documented. Doctors were predisposed to favor claimants to maintain community favor, and the judgment calls were getting harder. By 1876, claims had mutated from being for "disability contracted in the service" to questions "of sequels to disabilities incurred in service." In 1883, a 22-person "Medical Department" dealt with these "intricate medical problems [that] are multiform and perplexing" and performed work "astonishing in quality and quantity."

Two alternative systems were proposed but not enacted. One idea was a system of physicians employed "at an ample salary to enable them to devote their entire attention to the duties" of examining claimants and writing examination certificates to the satisfaction of the pension office. A second idea was to require examinations only when necessary, which Commissioner J. A. Bentley proposed after experiencing the difficulties of the first biennial examination of his tenure (1877), since it was clear that the survivors of the war, whose average age was 41, would not, due to their "advanced years," experience less disability than they now had.

Legal Formalities

As early as 1862, some people were under "erroneous impressions" that there were "serious obstacles, and the interposition of needless and burdensome formalities, in the prosecution of a just claim for a pension." On the contrary, the commissioner believed that

any claimant of ordinary intelligence and education can on applying directly to this office for forms and instructions suited to the particular case, establish his claim, and secure its prompt administration, without any other aid than that which will readily be given him by the magistrate before whom his declaration is to be executed. Nothing is required of the claimant which is not necessary and, in most instances, conveniently obtainable.

In 1863, he noted that decisions on claims with complete evidence would not be delayed more than two months before a final decision. Some cases languished due to "the inattention of applicants or their attorneys to essential requirements distinctly made known to them" or because the pension office was waiting for other government departments to provide necessary record evidence of service, death, or disability. In 1871 Commissioner Barrett noted the "general policy" was "liberal construction" of the "manifest letter and spirit" of the pension laws without any "unreasonable or unwarrantable" requirements yet "exacting a rigid compliance with such rules and regulations as are deemed essential to guard against the admission of fraudulent or improper claims."

Then, as now, claimants wanted swift action on their claims. Despite the "reasonable degree of promptitude" with which the pension office dealt with claims, "one of the principal sources of complaint" was the "failure to answer promptly letters of inquiry." It was a perception problem because "the greater number of claimants for pension are persons who have but little idea of the extent of the operations of the Government, and consequently, the time necessarily consumed in attending to their demands appears to them unreasonable delay.

During the fiscal year ended June 30, 1875, the bureau received 24,494 pension claims, 51,000 reports from the War Department about soldiers' service and hospital treatment, 15,600 communications from other government departments, and 81,000 pieces of additional evidence from other sources. The pension office used nearly $23 million in postage (almost $74 a day) responding to inquiries. (Postage was 3 cents per 1/2 ounce to U.S. addresses.) Even with all this activity, some claims lingered unresolved for years due to difficulties in obtaining evidence. Of the 1,651 pension applications filed before July 1862, fewer than half—721—were approved before July 1865; another 126 were approved during 1866–1875; and another 204 were approved during 1876–1885. (The remaining 600 had been disapproved, abandoned, or remained pending.)

Over time, proving disability from military service became more difficult due to "death and removal of witnesses by whom the facts . . . could have been proved, [and] the difficulty of obtaining evidence in support of claims." Commissioner Baker noted that "a large proportion of cases presented in recent years remain unestablished" because, "although disability arising from obscure disease may have had its origin in the service, yet there being no medical or other record of its existence . . . as they were not under medical treatment for the same for a considerable period after the date of discharge." Moreover, "the difficulty of rendering a just decision" was complicated by "habits of applicants since the date of discharge [that] are productive of disease."

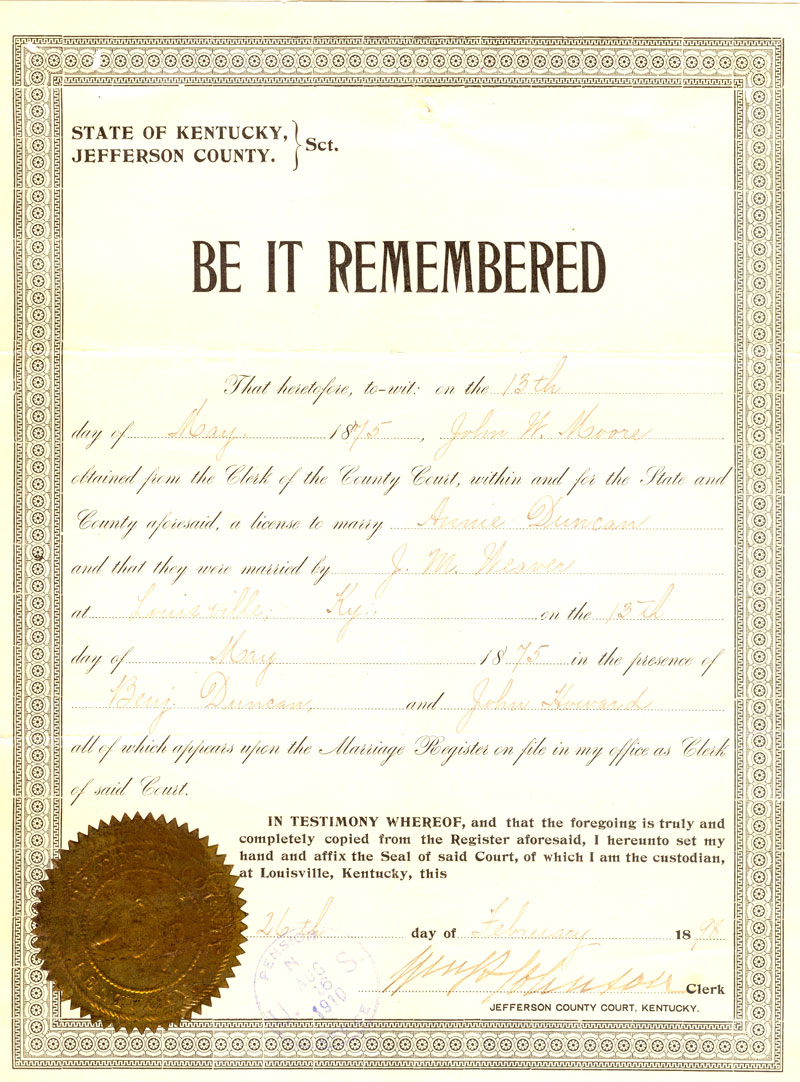

The pension office could allow a widow's pension based on evidence of cohabitation but, ironically, could not legally terminate a widow's pension because of cohabitation. Because marriage records had been created haphazardly in many places, or not at all, pension office custom was "to accept evidence of cohabitation and general recognition as husband and wife, as sufficient proof of marriage to entitle to pension in cases where it is clearly shown that more satisfactory proof cannot be furnished." The pension files are replete with affidavits of persons who may not have witnessed the marriage ceremony but who could testify that John Doe and Mary Doe held themselves out as being husband and wife and were so accepted in the community.

On the flip side, since remarriage meant the loss of a widow's pension, some "widows, in increasing numbers, cohabit without marriage . . . for fear of losing their pensions thereby," while others "openly live in prostitution for the same object." Thus the government was placed in "in the strange attitude of offering a premium upon immorality, of which it should be relieved." In the 1870s this "condition of lewdness destructive of good morals" was still rampant, but the pension office remained legally powerless to end a pension by declaring the cohabitation a remarriage.

Special Investigations

When government gives away money, some people hope to benefit by fraudulent means. Pension office policy was "to detect, in advance, any intended frauds, so far as possible," and to promptly prosecute those who committed fraud despite its vigilance. Commissioner Christopher C. Cox acknowledged in 1868 that "impositions are daily practiced upon this bureau" despite its best efforts at detection. Clerks investigated cases of reported fraud, a "much sought for" assignment, for it was "customary to intrust this work to those who while on leave of absence desire to defray the expenses of the journey by some official occupation in via." Thus clerks conducted compensated government business in the middle of personal travel.

The work of the "special service," as it was often called, saved money. In 1873, for instance, focus on "cases of suspected fraud, where pension has already been allowed," resulted in "direct saving to the Treasury . . . many times greater than the sum expended in maintaining it" in addition to indirect savings through deterrence of other potential offenders. In 1874, 411 pensioners were dropped whose claims had "had been established through intentional violations of law" at an annual savings of $41,525. Other special agents were assigned to investigate pending claims; in 1874, those agents recommended rejecting 133 claims that probably would have been allowed, saving $61,660. In 1878, Commissioner Bentley bemoaned his lack of authority "to go out and hunt for fraud" since he was statutorily limited to investigate "only as suspicion attaches . . . in the usual routine of the office."

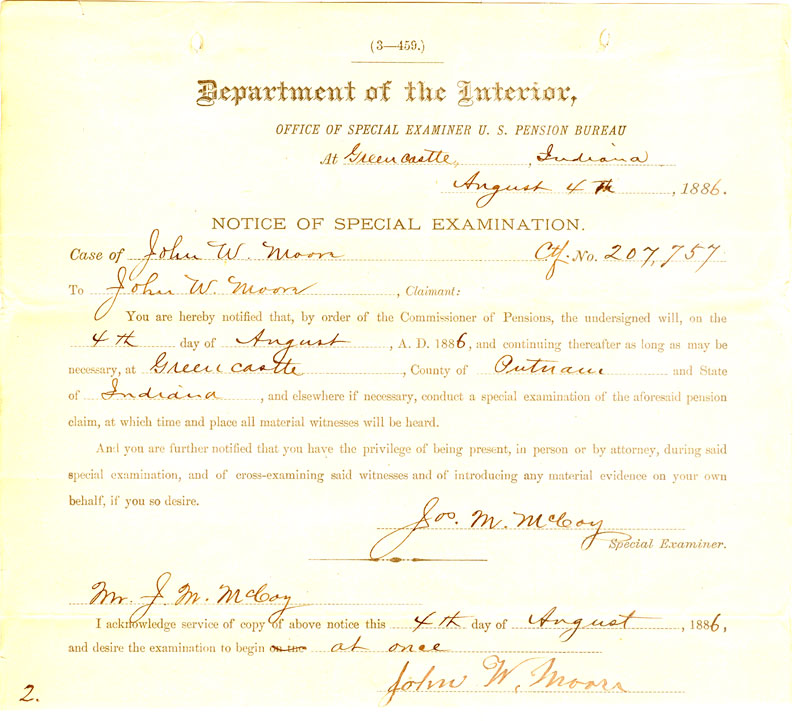

On July 15, 1881, the Pension Office changed the manner of conducting special examinations. Before that date, special examiners obtained evidence without claimants being notified or present to hear testimony by others. Under the new quasi-judicial system, examiners worked their cases "from the ground up" as claimants were notified of a hearing scheduled at their own home and given opportunity to testify and to present witnesses on their behalf. Testimony was recorded in the form of a narrative affidavit made under oath. The new system was "conducive to the establishment of a good feeling between claimants and the Pension Office." During the 1883 fiscal year, 240 special examiners completed 6,290 investigations.

Two cases investigated by special examiners show the breadth of their work. On, May 3, 1880, 75-year-old Mercy Ives of Denmark Township, Ashtabula County, Ohio, finally applied for a mother's pension. Her claim that she had been dependent upon son Harrison P. Ives rang hollow due to the 15 years that had passed between his wartime death and her application. Special Examiner Joseph M. McCoy took testimony from Mercy and others in July 1889 and concluded that Mercy's husband, Giles, who was still living, "has been in comfortable circumstances all his life and the idea of the claimant [Mercy] being dependent on the soldier [Harrison] is not entertained seriously in their neighborhood." Even after the death of another son, Lewis, in 1873, "they were not cramped even then." The pension application was denied.

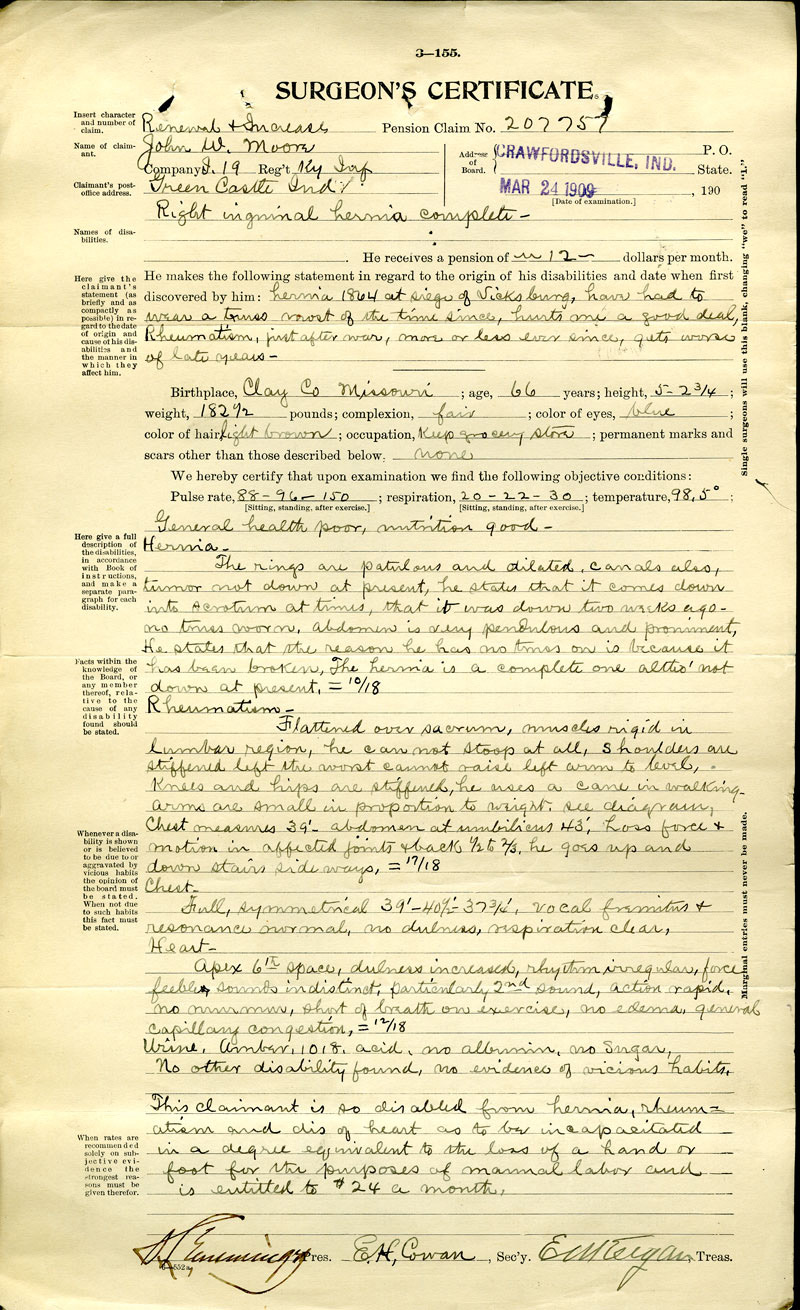

John W. Moore, a pensioner based on a hernia caused by military service, later requested an increase due to foot problems. To determine the merit of this additional claim, three separate special examiners went to Indiana (Moore's home), Kentucky (his original home), and Nebraska (where one comrade-in-arms lived) to take testimony regarding whether Moore had developed corns and bunions on his feet during military service near Vicksburg, Mississippi. The Nebraska special examiner, H. J. Brown, concluded there was no merit to the claim and that it should be denied "without further expense to the Government."

In 1871, Commissioner Baker suggested that he be authorized to publish a list of pensioners so that each "would have to confront his neighbors and the public as to his right to a pension" since invariably "suggestions leading to the detection of fraudulent pensions" reached Washington from neighbors in "the vicinity of the pensioner's residence." This list was finally published in five volumes as the List of Pensioners on the Roll, January 1, 1883 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1883).

Payment

"A simpler system is urgently demanded," noted Commissioner Barrett in 1862. Under the existing system a pensioner obtained his semiannual payment from the designated pension agent; there were 58 by 1871. If the pensioner could not travel to the agent, he could designate an attorney-in-fact to collect the pension for him. This designee could be a relative but more often was an enterprising person who charged a fee for the service. In 1865 the commissioner again found himself lamenting the exorbitant charge of $2 to $5 charged by intermediaries for their services, "who, availing themselves of the ignorance of the pensioner" create the impression that "their services are indispensable to their clients" despite the reality that free blanks, "furnished, without expense, to all pensioners who desire them," could be "readily made out by any intelligent person who can read and write, requiring only the expense of fees for administering the oaths required." The pension office solved part of the problem in 1865 by requiring those who lived near payment agencies to present themselves in person, but the overall system required improvement.

Commissioner Barrett's November 1864 report concluded that "there is apparently general satisfaction with the present organization for the disbursement of pensions." Despite the "urgency" originally declared in 1862, the system remained in place for decades. The number of agencies was reduced from 58 to 18 in 1877.

Pension Office Employees and Buildings

By 1866, pension office employees were already busy enough to be considered overworked and underpaid. Pension office clerks held positions "eagerly sought, and secured only upon the highest testimonials" from members of Congress and others. But once they left home, family, and friends and began living in Washington, D.C., they discovered that "they are accumulating nothing, but are actually worse off than those associates left at home to pursue private vocations." In 1871, Commissioner Baker noted that the workload had been "largely increased by new legislation, repeated modification of old acts, necessary changes in the ruling resulting therefrom, and . . . many of the claims now pending are old and difficult, requiring more time and care to establish or reject." Over the years, pension commissioners repeatedly asked Congress for modest increases in staff and increased pay rates, especially for key "clerks" (division heads) to place them on par with those performing similar duties at other agencies. Hiring decisions gave preference to veterans and to their widows and children.

At the end of the fiscal year, June 30, 1881, there were 784 pension office employees annually earning $931,350. Congress chose to appropriate only $794,630 for salaries for the fiscal year beginning July 1, 1881, which "made necessary a very large reduction of the force, already too small to keep up with the increasing annual influx of cases." The reductions in force, including the loss of "many efficient men," plus reductions in salary, "were soon and disastrously felt in the work of the office."

On July 2, 1881, President Garfield was assassinated. His long fluctuation between life and death, his funeral, and the inevitable distractions of a new presidential administration cost "the whole force" two months of work. Finally, about November 1, the reduced staff returned to its previously efficient pace of work. The reduction was temporary; the staff grew to 1,500 employees by June 30, 1885.

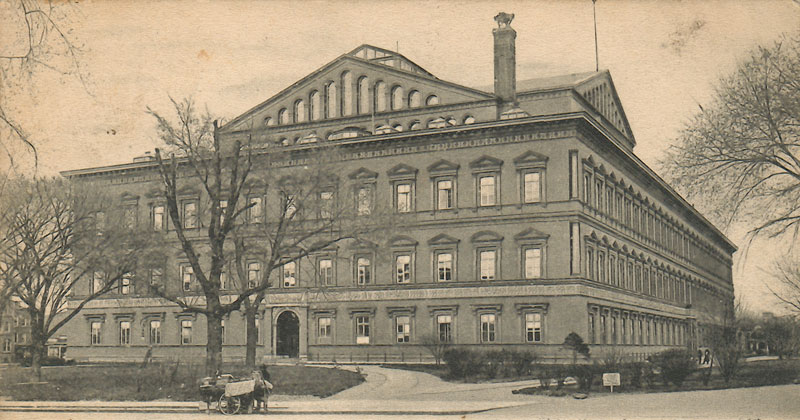

In 1868, working conditions were rather pitiful. The rooms in which clerks worked were too crowded to efficiently conduct government business and unsanitary enough to be blamed, in part, for "a number of deaths from typhoid fever [that] have occurred in the department within a few months." In 1875, Commissioner H. M. Atkinson noted he had the same objections to the continued use of Seaton House and other nearby buildings as his predecessors. Pending claims files were stored on the ground floor in the hope that they could be extracted in case of fire. But files of approved claims had to remain elsewhere in the building. "In the event of destruction of the building by fire, but a small portion, if any, of them could probably be removed," judged Commissioner Atkinson. He soberly concluded that the "destruction of the valuable records of the Bureau would be equally disastrous to the Government" as it would be to claimants. Congress was again "urged to provide for a building better adapted for the purposes of a public office."

By September 15, 1876, thanks to Congress, the pension office was able to lease "a better building for an office." However, accommodations at the "Old Kirkwood House" at 12th Street, NW, and Pennsylvania Avenue, and the "Eagle Building" at 13th Street, NW, and Pennsylvania Avenue, were still crowded and not fireproof. Site work for a new pension building finally began on November 2, 1882, covering the entire block bounded by Fourth and Fifth Streets, NW, and F and G Streets, NW. By December 1885, the entire workforce and all its voluminous records were housed under one roof for the first time in years. By September 3, 1887, $886 million had been spent on this magnificent building, which today serves as the home of the National Building Museum.

Military forces begin to stand down at the cessation of armed hostilities, but a war's effects do not end until the last veteran enters the bivouac of the dead. Instead, war's end signals the ramping up of civilian services for veterans. After the Civil War, the pension office expanded to handle the unprecedented 4,000-percent growth in its caseload from 1861 to 1885. It devised better policies and procedures by which to fairly evaluate the complex and evolving medical claims of Union veterans as well as the marriage claims of widows and the relationship and dependency claims of other family members. The requirement to submit adequate evidence and records to prove claims was not insisted upon to glorify the bureaucratic process, but to attempt to ensure that taxpayers' dollars were not fraudulently or wastefully expended.

Claire Prechtel-Kluskens is a projects archivist in the Research Support Branch of the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, D.C. She specializes in records of high genealogical value and writes and lectures frequently.

Note on Sources

This article uses the generic term "pension office" to describe the government agency that handled veterans' claims. The official agency name changed many times, and has been called the Department of Veterans Affairs since March 15, 1989.

Quotations in this article are mainly taken from the annual reports of the commissioners of pensions. The year mentioned in text matches the year of the annual report. These reports were published in the U.S. Congressional Serial Set. Statistical data in annual reports pertain to the fiscal year ending June 30. However, since they were frequently written several months into the new fiscal year (October or November), the commissioner's commentary frequently includes information about the new fiscal year.

Statistics on the size of the pension office workforce are from the Official Register of the United States, Containing a List of Officers and Employees in the Civil, Military, and Naval Service for the appropriate year.

The numbers of pensioners given in the first paragraph understate the total number who had received pensions to 1885, since some pensioners had been dropped from the rolls for various reasons. There were also many "dead" files, which claimants had abandoned. More claimants were yet to come; in 1882, there were still 1 million living Union Civil War veterans for whom no pension file had yet been created.

Complete rosters of the civilian doctors who conducted medical examinations for the pension office are provided in the 1863 to 1870 and 1872 to 1875 reports. The 1870 report included facsimiles of the forms and instructions given to them.

The two cases of denied claims cited are documented in Report by Special Examiner Joseph M. McCoy, July 21, 1889, in Harrison P. Ives (mother, Mercy Ives), private, Co. E, 39th Ohio Infantry; Civil War Pension File MO 264599; and Report by Special Examiner H. J. Brown, Nov. 5, 1886, in John W. Moore (widow Anna Moore), Private, Co. I, 19th Kentucky Infantry; Civil War Pension File WC 708353, both in Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Record Group 15, National Archives Building, Washington, DC.

For another examination of the pension office during this period, see John William Oliver, History of the Civil War Military Pensions, 1861–1885 (Bulletin of the University of Wisconsin No. 844) (Madison, WI: 1917).