Archival Vintages for The Grapes of Wrath

Winter 2008, Vol. 40, No. 4

By Daniel Nealand

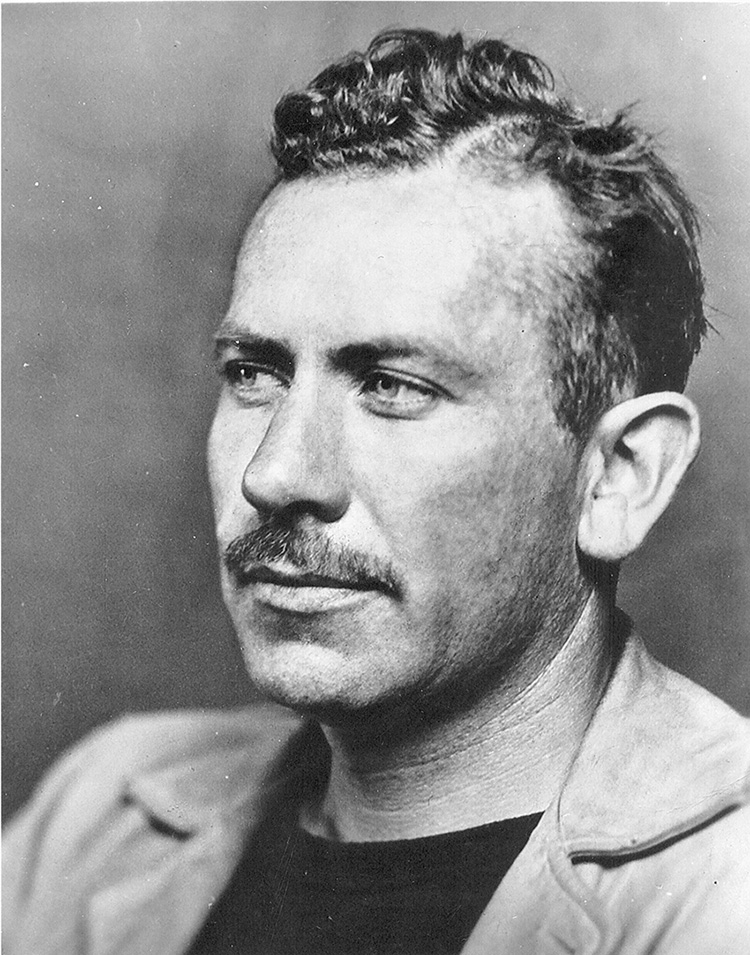

At the beginning of John Steinbeck's perennially popular (and still controversial) masterwork, The Grapes of Wrath, two dedication lines appear: "to Carol who willed it" and "to Tom who lived it." Carol, of course, was the author's wife, who originated the title for Steinbeck.

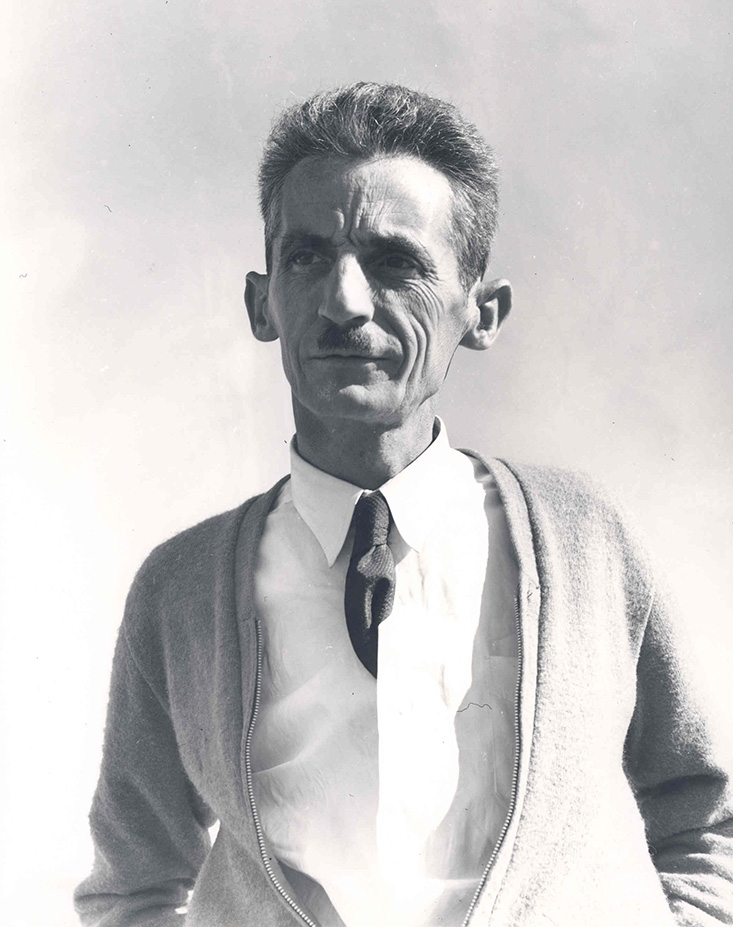

Most readers logically assume that the second line targets Tom Joad, the archetypal protagonist whose shade still walks the land "wherever there's a fight so hungry people can eat." But the line actually refers to Thomas E. Collins—a nonfictional "character" whose ghost would likely be found walking right alongside that of Tom Joad.

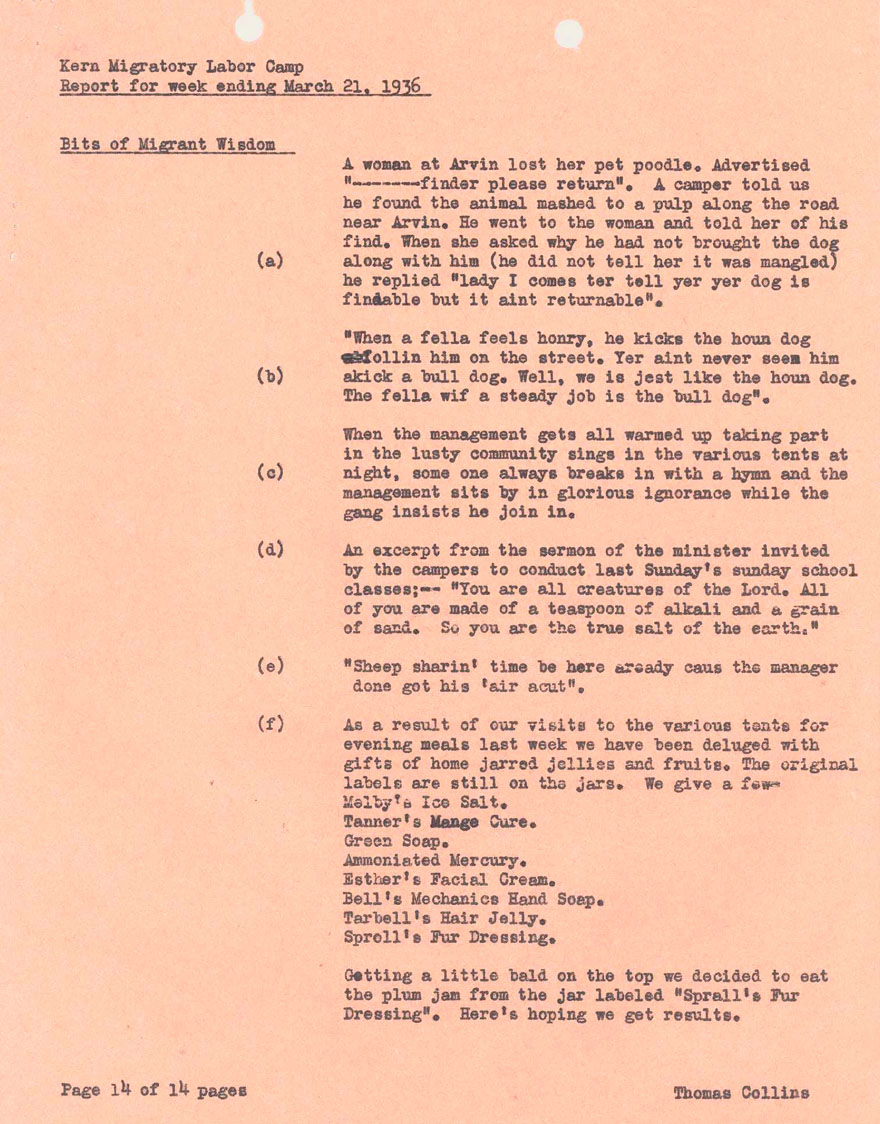

There are significant relationships between the worlds of "the two Toms." First, the real Tom Collins steps over into The Grapes of Wrath as the model for the character "Jim Rawley" in chapters 22–26. But in addition, both Steinbeck and his biographers have acknowledged a major influence that flowed into the novel from a wealth of federal documentary source material provided by Collins. Most of the latter is preserved and available for public research today as a unique, absorbing, somewhat "quirky" treasure held by the National Archives–Pacific Region (San Francisco): the narrative reports, mostly 1935–1936, of California federal migrant labor camp manager Tom Collins. 1

As the 75-year remembrance of the New Deal period passes into the 70th anniversary for The Grapes of Wrath, it seems a good time to again visit these "Tom Collins documents," which in a rare occurrence for government reports, were regarded as "worthy literature" by no less an expert than Steinbeck himself.

Okie Migrants and Federal Camps in California

In 1936, when he met Steinbeck, Tom Collins managed the Resettlement Administration's Arvin/Weedpatch federal "Migratory Labor Camp" for migrant agricultural laborers in Kern County in southern California. "Weedpatch camp" appears in The Grapes of Wrath in chapters 22, 24, and 26. The "campers" at Weedpatch were among thousands of mostly rural Dust Bowl refugee families newly arrived in California in search of farm-related work. They came mostly from Oklahoma, southwestern Missouri, central Texas, and western Arkansas. 2

Most were victims in one way or another of a crop-killing 10-year drought or "tractoring out" (farm mechanization), rather than of the terrible Dust Bowl storms per se, which struck a little farther west. 3 Most had been farm laborers, tenant farmers or sharecroppers; there were also some small farm holders and others. Stereotyped by mainstream resident Californians as "Okies" or "Arkies," these newcomers furnished a new and major source for traditionally subsistence-level migrant agricultural labor, harvesting fruit, vegetable, and cotton crops in verdant well-irrigated central California valleys dominated by the large, often corporate-owned agribusiness operations described by Carey McWilliams in his renowned study Factories in the Field.

Since the latter 1800s, white "fruit-tramps/bindlestiffs" and various ethnic minorities—Chinese, Japanese, South Asian, Mexican, and Filipino—had served as seasonal "migrant armies" fated to harvest large-scale California farm crops. All had faced exploitation, meager pay, and severe living conditions. But generally, they had truly "come with the dust and gone with the wind," moving on after the harvests. In contrast, the 1930s Okie migrant influx brought entire families that, having nowhere else to go, remained in the valleys during times of scarce or no employment, generating consternation among valley residents and further straining state and local social services already stressed by the Depression. 4

As noted by historian James Gregory in his classic American Exodus, the agricultural labor Okies comprised only a portion of a much larger stream of nearly 1,300,000 emigrants to California from the southwestern southern states during 1910–1950. 5 Many arrived in less desperate straits and adapted more easily to their new, sometimes urban surroundings. 6 Still, the thousands of California migrant labor families chronicled by Steinbeck, Collins, Sanora Babb 7 and others, had it very bad—sometimes far worse than the Joads.

The destitute Okie agricultural migrants had been drawn to California by hopes for employment or even a new start on small-holding farm ownership. Word-of-mouth furnished much of the impetus, and there is evidence Arizona had more to do than California with the cross-country lure of grower-produced ads and handbills as portrayed in The Grapes of Wrath. 8 At any rate, there is no doubt that during the 1930s, large California growers took advantage of a huge bulge on the "supply side" of agricultural labor to drive down wages. Okie migrant income hovered around and sometimes descended below bare subsistence levels, and that was for the "lucky ones" who found employment. At one point, for every available crop-picking job at even the most meager recompense, there were 3 to 10 workers who needed it. 9

In 1935, with Tom Collins playing a major set-up role, the Resettlement Administration (RA, Farm Security Administration [FSA] as of 1937) established a chain of federal "Migratory (migrant) Labor Camps" up and down California's agricultural valleys. At their peak just before World War II, 18 camps, including 3 "mobiles"—from Brawley in the south to Yuba City in the north—featured sanitary, low-cost, and very basic living facilities (mostly tent sites) for migrant labor families. Populations could reach around 500 or more per camp.

Early on, opposition from powerful growers' organizations, as well as lack of support from the federal sector, 10 divested the RA/FSA's regional office in Berkeley of any hope of accommodating the entire California migrant farm labor population in federal camps. The agency fell back toward more limited aims: to demonstrate to both the growers and California at large that it was possible and advisable to provide low-cost, relatively humane living conditions for migrant workers and their families and that there was no basis for common tendencies to brand the newly arrived migrant population in California with such terms as "morally degenerate," intrinsically "uncivilized," etc.

For Okie residents, the camps strove to provide health services and education, community, and a road toward "depolarization" with hostile mainstream Californians. The federal camps served as comparative oases of health, human dignity, and relief from the often inhumanly degrading conditions prevailing elsewhere.

Steinbeck, Collins, and Migrants

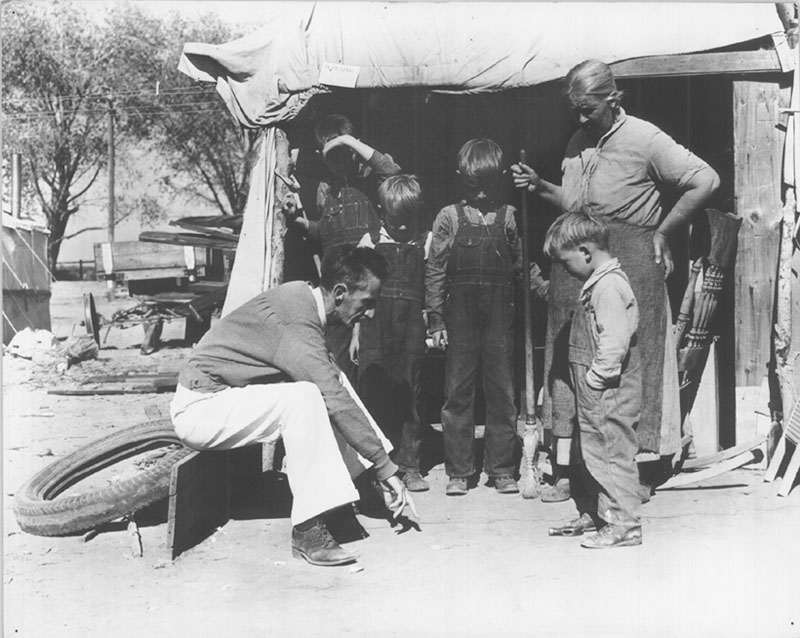

Collins and the migrant laborer families at the Resettlement Administration's Arvin/Weedpatch federal camp hosted several Steinbeck visits beginning around August 1936, when the author journeyed from his Los Gatos home to do fieldwork for the seven-part San Francisco News series "Harvest Gypsies." 11 But their relationship did not stop at Weedpatch. With the approval of the RA/FSA regional office in Berkeley, Collins also served as Steinbeck's primary "migrant liaison" at various times between 1936 and 1938. The two traveled up and down the San Joaquin valley in Steinbeck's legendary "old pie wagon," 12 gathering information and offering aid in several crisis situations.

During this period, Steinbeck's nonfictional portrayals of migrant squatter camp conditions were grim, stark, and shocking. The innovative federal photojournalism of Dorothea Lange and others, "on the road" for the RA/FSA starting in the mid 1930s, captured for the public eye unforgettably haunting, dramatic images of destitute Okie families: journeying in often ramshackle "jalopy caravans" along their "desolation road" to California (Route 66) or "wasting away" within the shockingly squalid California ad-hoc irrigation ditch-bank squatter camps and "Hoovervilles."

Previously, the mostly non-European minority migrant labor force in California had been exploited and "expected" to accept living standards far below the median for most Americans. But most of America had never actually "seen them"—especially like this. Publicity relating to the Okie migrant plight took hold and spread through the local and national media. By mid-1938, federal curtailment of California cotton acreage and related reduction in employment opportunity, a continuing influx of farm job-seekers, severe flooding, resultant deprivation, and vivid documentation made the peaking "California Okie crisis" into "continuous front-page news." 13 This helped "prime the pump" for the explosive sales of the novel The Grapes of Wrath upon publication in 1939 and for the popularity of the John Ford movie version in 1940.

In many respects kindred spirits, Steinbeck and Collins shared a commitment to the uphill fight to better Okie migrant laborer and family living conditions. The situation was often dismal enough at the grower-owned camps they visited. But at the ditchbank "squatter camps" and Hoovervilles, conditions had descended to depths hard to acknowledge. Steinbeck and Collins saw, documented, and toiled to alleviate mind-numbing, spirit-killing poverty, squalor, epidemic disease, malnutrition, and outright starvation among a vast valley assemblage of least 100,000 (historical estimates vary)—often lacking even subsistence in the most abundant "food-basket" of the nation.

During Steinbeck's San Joaquin valley migrant journeys with Collins, they toiled and lived alongside destitute migrant labor families as well as rendered emergency assistance. Efforts culminated in a two-week mission, with the two "dropping in the mud from exhaustion" 14 while trying to rescue 4,000–5,000 squatter camp families stranded during the terrible Visalia-Nipomo floods of February 1938—"not just hungry but actually starving" as noted by Steinbeck. 15 According to Robert De Mott, this horrific experience, etched in acid upon Steinbeck's consciousness, galvanized his commitment to The Grapes of Wrath. 16

While at work on the latter, Steinbeck had at his side Collins's official federal narrative reports as well as correspondence. Previously, Steinbeck had tried to aid Collins in an unfulfilled effort to get them published, even doing some editing work. In 1936 Steinbeck declared to writer and friend George Albee: "Now I'm working hard on another book which isn't mine at all. I'm only editing it but it is a fine thing. A complete social study made of the weekly reports from a migrant camp." 17

As time passed, all other projects gave way to The Grapes of Wrath. But there are indications that Steinbeck believed that basing many of his fictional California migrant scenes and contexts on nonfictional documents like the Collins reports might help when the firestorm of criticism rained down following publication of his novel. Notable for its duration and intensity, the backlash featured such events as "book-burnings in Bakersfield." 18

The Reports

Prominent Steinbeck biographers and California Dust Bowl migrant historians, not to mention numerous thesis-writers, have come to the National Archives–Pacific Region (San Francisco) to research the Collins reports and related records of the Farmers Home Administration (Record Group 96). Steinbeck biographer Jackson J. Benson "rediscovered" the 1930s FSA migrant camp reports there during an early 1970s quest to find and write more about Tom Collins.

Thanks mostly to Benson's dogged biographical detective work, we know that the federal migrant labor camp period was likely the high point of Collins's far from run-of-mill life. Born out of wedlock, raised in a Catholic orphanage, and drawn at one point toward priesthood, Collins listed his educational background as four years at prep school plus a year at a possible "diploma mill" teachers college from which, when convenient, he claimed to have received a doctorate. During the early 1920s, he worked as supervisor/organizer of public schools at the Guam Naval Station. He also traversed the Amazon jungle with his young ex-socialite wife (the second of three) while fleeing from her family's lawyers. 19

He came to the Resettlement Administration in 1935 from a job as director and organizer of shelters and labor camps for the Federal Transient Service in San Diego County and Los Angeles. In his June 1935 job application, Collins recorded a salient attribute: "I have the ability to . . . successfully handle people without coercion or force." 20

Wearing the face turned toward his RA/FSA superiors when writing the reports, Collins sometimes commented on low levels of intelligence for certain adult migrant individuals or groups, especially in comparison with their own children. 21 He remarked on major initial "learning difficulties" especially regarding hygienic education. In his view, these were attributable mainly to the sociocultural/psychological trauma stemming from prolonged deprivation. 22 His anecdotes about the migrants sometimes made light of what he regarded as primitive, superstitious and/or ignorant beliefs and customs. Sometimes the comments sounded like laughing at, not with—though he also laughed at himself. Collins's reports also document some unsavory migrant behavior such as wife-beating (or occasionally vice-versa). His usual laissez-faire position: "A man's tent is his farm." 23

Some references can be seen as condescending, such as "these simple, honest, full-hearted, deserving people." 24 But he also wrote repeatedly that the spectacular quality-of-life upgrades that others found so amazing at his federal camps should be "justly credited to the migrants themselves." 25 Collins saved his special scorn for less honest, more convoluted, and sparse-hearted folk such as exploitive growers, educated nose-in-air social workers, and "His Satanic Majesty, Caesar Augustus Hearst" (William Randolph Hearst). 26

Some recent historians have accused Collins, Steinbeck, Lange, and others of seeing Okie migrants through a lens distorted by urban elitist liberal "reform agendas" while neglecting to attend to and preserve authentic Okie culture. 27 This view seems not to recognize that the real foundational concern of these three—the need for relief from sustained socioeconomic trauma and severe human misery—is a precondition for cultural survival and recovery.

The reports as a whole, as well as accounts of his managerial conduct by first-hand observers, reveal a complex and mainly constructive portrait of Collins. Regarding his behavior toward the migrants, he noted in an early August 1935 report that he was "on the spot at all times." 28 Shedding bureaucratic trappings, Collins chose to live and work in close, constant, extensive, and deliberately visible personal contact with migrant camp residents, where "one false move, and he loses the confidence and respect of the campers." 29 He later commented, "Hypocrisy, pretense, insincerity, lack of interest in their problems and in them—these evils we can never hide from them . . . and their justice is efficient, final and swift." 30

With the migrants, Collins combined the straightforward aspect of the "plain-folks American" with a daunting regimen of 24/7 on-call caring and public service. 31 In a short piece included in America and Americans, Steinbeck gave some insight into Collins's dedication:

The first time I saw Windsor Drake [Collins] it was evening, and it was raining. . . . I drove into the migrant camp, the wheels of my car throwing muddy water. The lines of sodden, dripping tents stretched away from me in the darkness. The temporary office was crowded with damp men and women . . . and sitting at a littered table was Windsor Drake, a little man in a damp, frayed white suit. The crowding people looked at him all the time . . . his large, dark eyes, tired beyond sleepiness. . . . There was an epidemic in the camp—in the muddy, flooded camp . . . every kind of winter disease had developed: measles and whooping cough; mumps, pneumonia, and throat infections. And the little man was trying to do everything. He had to. . . . 32

For Okie farm migrants reeling from the terrible treatment meted out elsewhere in California, the experience of Collins's "neighborly" caring manner, dedication, and public "servant-leadership" must have come as a dramatic, welcome contrast. It may have generated a sort of "positive culture shock" that partly explains FSA migrant camper receptivity to his guidance during 1935–1936. At any rate, it earned him a tremendous reservoir of credibility with Marysville and then Weedpatch migrant labor camp residents. He tapped into this with great effect while using tactfully packaged instruction, friendly suggestion and encouragement, and the attitude of the "Good Neighbor" (his signature phrase) to foster individual, family, and camp community democratic self-help programs in health, hygiene, nutrition, baby and child care, education, daily government/law enforcement, and recreation.

Time and time again in the reports, Collins conveyed respect, esteem, and faith that the destitute, despised migrant Okie families, given a place to stand and a chance, were capable of conduct at least on and perhaps above the level of the mainstream California society that had so far brutalized them. Combined with Collins's management style and programs, the minimal amenities at Weedpatch camp furnished the foundation for a gently guided, generous, high-standards, self-governing "community of caring" at Arvin/Weedpatch. This amazed visiting farmers, politicians, social workers, and others who had previously believed migrant Okies to be inherently incapable of such achievements. Steinbeck, his sympathies already with the migrants, was also mightily impressed.

Collins's views of migrant capabilities evolved alongside their own story of recovery at his prototypical camps. In September 1935 at Marysville, he had found it "very gratifying to see what we can do for these people simply through . . . giving them some voice in the camp routine . . . they do very well under proper supervision and guidance." 33 A year later in October 1936, Collins observed that the migrant Okie community at Weedpatch camp had, even during "down times" of scarce employment, "demonstrated beyond a doubt just how little they need us down here to manage their affairs." 34

The reports follow a form fairly consistent with the "Instructions to Camp Managers" approved by initial regional RA/FSA camp community manager Irving W. Wood, 35 but which Collins at least had a hand in writing. Usually written and sent to the regional office weekly or biweekly if things got too busy, the Collins reports usually contained most of the following interesting components:

- Statistics: Reports noted the number of resident camp families and individuals, illnesses, destitute persons, persons dismissed from camp (with reasons), referred to other agencies, employed, unemployed, children at camp, treated at camp first aid stations, and children by school grades. They also recorded the classification and number of camper families by state of origin and by occupation. In addition, Collins noted the number checking in and checking out, sometimes with notes on local travel origins and destinations. Oklahoman migrant families always won hands down in terms of Weedpatch camp population. A September 1936 report recorded "Oklahoma 56, Arkansas 4, Texas 8, Missouri 6, California 7," and a few each from eight other states. Similarly, farm labor outpaced all other pre-California occupations, as in "Farm Laborers 63, farm renters 10, farm owners, 8," and one to three for assorted others. 36

- Types, rates paid, and notes for any employment, such as: "Fruit picking. Wage rates $.25 per hour. Average weekly earnings $15.00 based on 10 hour day" (July 1936). 37

- Commentary on the labor conditions including employment, labor supply and demand, grower practices, worker reactions, unrest, disputes, and strike situations.

- Notes on migrant living conditions at the federal camps and also the off-site local, grower-owned, private fee, and ditchbank squatter camps/Hoovervilles.

- Sections about camp organization, government, and programs for health, education and recreation. Collins was an advocate and the chief on-the-ground architect of what Regional Director of [migrant camp] Management Eric Thomsen called "functional democracy" as a way to run the camps. 38 By various noncoercive methods, federal managers were to educate, encourage, and empower the migrant residents to govern themselves in most daily affairs through elected camp committees. This approach worked very well for Collins in 1936, though much less so with some other managers and especially after 1937, when FSA destabilized the situation by mandating shorter stays and more frequent turnovers of camp residency for migrant families. 39

- Newspaper clippings with commentary and a log of visitors and contacts. From the latter we know, for instance, that Steinbeck visited Weedpatch camp in August 1936. 40

- In addition, the reports of Collins and several "disciples" also contained "bits of migrant wisdom" relating observations and anecdotes about goings-on among the residents. Though some vignettes can admittedly be seen as demeaning, the reports overall show an underlying respect, sometimes bordering on "romantic reverence," for a straightforward, resourceful people who stubbornly persevere, somehow keeping hope alive in the face of challenges far more harrowing than those faced by the "average American." The reports feature transcriptions of migrant poetry, songs, letters, and conversations.

Collins often tried to capture the regional flavor of "Okie dialect." Compared to Steinbeck, Collins exaggerates, with frequent gratuitous misspellings, as in a February 1936 example: "When we aswallas the last been our innards will haf ter shak the dise ter see who agits it." 41 Still, Collins's attempts may have influenced the more muted and readable Steinbeck rendition. For instance, both use "purty" for "pretty." 42

One of the prime educational values of the Collins reports is that they help show the fundamental falseness of racial and cultural prejudice.

Along with other contemporary sources, they document how "standard sets" of negative stereotypes associated by the Anglo-American mainstream of the day with ethnic minorities (and mostly concerned with "blaming the poor") landed in this instance on destitute white, old-stock rural American Protestants slotted into the lowest rung on the "California caste ladder"—migrant farm laborers. The stereotypical slurs—inherently dirty, lazy, stupid, immoral, shiftless, parasitic, welfare chiselers, fundamentally incapable of joining mainstream American civilization 43 —tell us much about the sociopathology of prejudice and nothing about the groups victimized.

"Respectable visitors" to Weedpatch camp, from large growers to social workers, often confessed near-disbelief at the exemplary levels of conduct "these primitive people" 44 had achieved there in a very short time.

Finally, what stands out about the reports is Collins's literate and antibureaucratic style of government narrative report writing. He went to lengths (sometimes 20–30 pages) and took liberties to inject colors far beyond the "officialese" of most constrained, gray-scale government reports. Collins's creative latitude included both ad hoc headings and no-holds-barred candid, opinionated commentary, as in the following under "Labor, continued (September, 1936):"

The Shadow of Associated Farmers—the Hidden Hand

Rumors are now afloat that the Associated Farmers and the Cotton Finance Control agencies have been circulating through the valley in an effort to have the larger growers and others pay a cotton-picking scale between $.60 and $.80 per cwt [hundred-weight]. This is the advance guard preparing for the general price-fixing session to be held at Fresno, California on September 8, 1936. 45

Items like the above would have been of great interest to Steinbeck, who believed that Associated Farmers, the powerful large growers lobbying organization not particularly disguised as the "Farmers Association" in The Grapes of Wrath, were after him as their "public enemy number one." 46

Behind Collins's unique report stylings, there must have been purpose. An educated guess would be that he hoped to: capture and hold the interest of regional and higher RA/FSA and other officials; buttress precarious federal support and funding for the migrant camp program by highlighting spectacular challenges and achievements; as part of the latter, provide entertaining PR copy for RA/FSA; and familiarize readers with the California agricultural labor scene.

Influences on Steinbeck

Steinbeck spent considerable time with Collins and among the migrants at Weedpatch camp and elsewhere. The California section of The Grapes of Wrath therefore bears the stamp of numerous conversations as well as events and characters seen firsthand. In addition, as Benson notes, "There were deeper influences flowing from the camp manager to the author: influences of spirit, emotion, and attitude, which are difficult to measure or locate precisely . . . both had a knack for getting close to ordinary people and winning their confidence . . . both had faith that our democratic institutions, through the pressure of an enlightened citizenry, could and would conquer the inequities that appeared to be tearing the fabric of society apart." 47

Having the body of reports at his side also furnished Steinbeck with an extensive, rich documentary context for the imaginative surround in which he built the California section of the novel. The reports contained numerous portraits of labor conditions, domestic life, migrant character, "characters," and such significant components of Weedpatch camp life as the governing committees elected by campers.

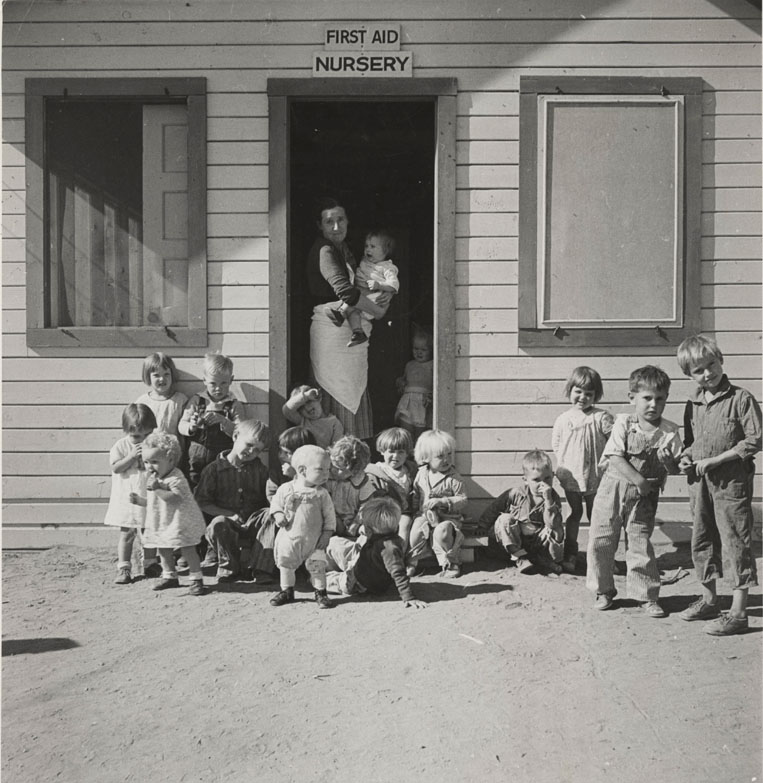

The committees were numerous, but three chronicled repeatedly in the reports appear in The Grapes of Wrath. The Central Committee saw to all-camp matters such as law and order, basic upkeep, and employment aid for the campers. The Good Neighbors Committee ("Ladies Committee" in Steinbeck) visited all tents to welcome new women and families, helped with sustenance, and introduced them to sanitary facilities and child-centered resources such as the clinic, nursery, and playground.

The Recreation Committee arranged for such events as baseball games with nearby settlements or farms as well as the orderly, liquorless, camper-policed "best dances in the county" featured in the novel. As Collins intended, such activities, besides boosting camp morale, helped break down barriers between the migrant campers and surrounding communities. This led to more jobs with growers who had previously vilified the FSA camps (filled with highly patriotic Okies) as "red-infested." 48 He was pleased to report instances when campers passed beyond the migrant agricultural cycle altogether and left for steady, long-term employment in the towns. 49

The reports feature numerous "items," from major to minute, that appear in the novel—from small farmer protests against large grower coercion aimed at cutting migrant wages, to the price for a cotton-picking sack if you have none. Sometimes these were inserted whole-cloth into The Grapes of Wrath, but more often they were reconfigured or "built-out" to serve the creative purposes of the novel.

The Collins report items also have an absorbing "story life" apart from The Grapes of Wrath. This storytelling strength is likely another reason the reports appealed to Steinbeck.

As one might expect, chapters 22 and 24 of The Grapes of Wrath—set mostly at the Weedpatch camp—contain the highest numbers of items correlated to Collins reports, though they appear elsewhere as well. The following are a few selected examples.

In chapter 8, Granma Joad exclaims, "Praise God for Vittory!" Collins records use of this phrase in April 1936 as the standard ending for letters to "folks back hum" he is typing for Weedpatch women campers. But it is also the signature declamation of "Reverend Georgie," the "Holy One," whom he hired as his housekeeper. Her description does not match that of Steinbeck's grim fundamentalist who terrorizes Rose of Sharon at the camp; rather, Georgie is depicted more as a voluble "space-cadet." Her saga begins in a May 1936 report and ends in September as she and her part-Cherokee husband, Noah, having recently launched their "Ark of Love," move on. Collins records Georgie's hobbies, perhaps in priority order: "1. entertaining visitors at manager's house, 2. having her husband rock her before he goes to work and for hours after he returns, 3. saving souls through her preaching, 4. holding revival services anywhere, anytime, 5. TALKING, and 6. Housekeeper." 50

"No cops" are allowed in Weedpatch camp without a warrant, finds Tom Joad to his relief (chapter 22). This policy is specified in the August 1935 "Instructions to Camp Managers."

"We won't have no charity," says Jessie of the Weedpatch Ladies Committee (chapter 22).: The characteristic Okie aversion to accepting charity or relief—the opposite of the stereotype—recurs in both Collins and Steinbeck. In February 1936 Collins quotes the Okie consensus: "jest as well haf all our teeth yanked out as ter go sit down, tell our life's history and ask for relief. Culd we only git a job for that's all we wants. We's able ter wuk and wants to wuk." 51

In the "croquet mallet incident," Ruthie Joad snatches a croquet mallet from another girl, acts tough, and cries afterward (chapter 22). In Collins, a very young newlywed does the mallet-snatching; 52 the "crying" part may come from a May 1936 report item in which Collins arranges and pays for a birthday party hosted by "the toughest kid in camp . . . we have seen her tackle three and four at a time and 'clean up.'" 53

Ruthie and Winfield get a shock from accidentally flushing a toilet (chapter 22). A similar incident appears in a Collins report from October 1935. 54 Throughout the reports, toilet, shower, and similar "plumbing hijinx" occur due to unfamiliarity of some rural migrant campers with basic modern sanitation technology. The committee suggestion of a "toilet paper dispenser that rings a bell" transfers from Collins (May 1936) to Steinbeck. 55

Much more serious are Collins's repeated battles with deadly disease outbreaks, especially among children, caused by the unfamiliarity of some rural people with basic hygienic theory and practice, horrid conditions at the squatter and grower camps, and sometimes the traumatic migrant shock and fatigue reported by Collins, Steinbeck, historian Walter Stein, and others. 56 At a Hooverville in chapter 18, Ma Joad notes, "we ain't never been dirty like this . . . I wonder why? Seems like the heart's took out of us."

Echoing numerous migrant sentiments recorded in the reports, Ma Joad and Rose of Sharon appreciate Weedpatch camp's hot water and laundry, washing, and bathing facilities. Due to opportunities for and the efforts of the migrants, the FSA camps generally furnished a spotless contrast to the festering situation at squatter, private fee, and many grower camps. Collins reports that by July 1936, Weedpatch resident women have taken over much of the clinic, nurse visit, nutritional, first aid, and well-babies program work, lessening his own toils. 57

Rose of Sharon mentions how "I'm to go see that nurse and she'll tell me jus' what to do so the baby'll be strong . . . all the ladies here do that" (chapter 24). There are numerous mentions in the reports of the well-baby program and how resident camp mothers embrace it. Collins, who cared most deeply about the children, seems to have especially loved dealing with infants. In August 1936, he celebrates Raymond, the "Perfect Baby": "Raymond seldom cries. He is always smiling. . . . Many times he sits on our desk as we go about the routine office work. At other times we can be found on the sewing project floor keeping Raymond busy while his mama runs a new suit of jumpers . . . on the electric sewing machine. What a baby!" 58

Early on at the Marysville migrant camp in 1935, Collins reports that "Complaints regarding drinking, gambling, and unnecessary noise late at night all appear to be things of the past since the campers committee entered the picture." 59 But later at Weedpatch, he notes an instance of "pappy rolling about in a dry ditch. Beside him was an empty bottle of gin . . . we appreciated the fact that he left camp to have his big snort of liquor." 60 The novel mentions two such "solitary ditch-bank drunks," the first involving Uncle John Joad (chapters 20 and 23).

The reports are also laced with Okie humor, as in this example from a January 1936 report: "With Roosevelt, we hunts our jack rabbits and milks 'em and turns 'em loose again to catch again when we needs 'em." 61 A similar Okie "jack rabbit fantasy" can be found in Steinbeck's chapter 27.

Regarding character, Collins seems to be talking about Ma Joad's strength (and Pa Joad's protests) when he notes that "during times of unemployment . . . the woman steps in as Master of the House." 62 And Tom Joad's instinctive bent to challenge head-on and strip away the puffery of others resonates with report items like the following, in which a migrant faces down a "pusher" trying to cut pay by force-speeding the pace of work.

Pusher: "You pack 15 boxes a day OR ELSE." Camper: "I been wuking here for 2 years, an I ain't had no one tell me I loafs on the job. . . . I ain't gonna pack 15 boxes because I ain't gonna put rotten grapes in these boxes to ship . . . so OR ELSE TO YOU AND LIKE IT. I ain't gonna quit...so what's your other OR ELSE?" 63

Steinbeck biographers note that partial inspiration for Tom Joad may have come from a Tulare FSA camp fugitive son of Weedpatch Camp Central Committee chairman Sherman E. Eastom, a bronze-faced, widely respected, no-nonsense figure. 64 Eastom's "eyes that miss nothing" in Collins become "eyes like little blades" for committee chair Ezra Huston in The Grapes of Wrath. 65

In 1937 Tom Collins left Arvin/Weedpatch "to act as traveling Field Superintendent out of the Regional Office . . . and to be ready on short notice to enter into the organization and management of any new camp, as ordered" a position also known as "Community Manager at Large." 66 After stints at various locations among which were Gridley, Thornton, and Calipatria, his luster evidently dimmed. Again a camp manager as of 1940, he resigned from the FSA in 1941, 67 having recently received $15,000 as technical director for the Grapes of Wrath movie. 68

The currency of "functional democracy" and the Collins community method also faded as economic conditions and pay improved, defense jobs opened up, FSA camp populations became more transient, and Collins-school "servant-leaders" gave way to managers accustomed to more bureaucracy and social distance between themselves and their clients. Steinbeck might have been disappointed to visit later camps where most residents were indifferent to clique-ish committees, 69 or where campers charged managers with "Hitlerism." 70

By 1940, California was on the way to ramping up industrially and otherwise for World War II. Over the next few years, pay and defense-related employment in California followed suit. With the "War Deal," the Depression came to an end, taking with it the California Okie migrant crisis.

However, The Grapes of Wrath lives on and on, and with it, that special sense of a greater, deeply human whole that comprises a sizable portion of the legacy of not only John Steinbeck, but also Tom Collins. For a time at least, as Steinbeck noted when writing it, Tom actually "lived it." That spirit shines through in the words of Robert Hardie, a Collins "disciple" selected to replace him as Weedpatch camp manager. Presaging Ma Joad's memorable words from chapter 20—brought forward to conclude John Ford's 1940 movie—Hardie declares in his report for the week of Christmas 1936:

"But come what may—we'll find a way through this thing—for we are the American people." 71

Daniel Nealand is director of the National Archives Pacific Region–San Francisco.

Notes

1.Weekly Narrative Reports, 1935–1936, Arvin (Weedpatch) file code 918-01 (Weedpatch Reports), Coded (Migrant Labor) Camp Administrative Files, 1933–1945, boxes 22–23, Records of the Office of the Director, Region IX (Berkeley/San Francisco), Farm Security Administration (1937–1946) and Resettlement Administration (1935–1937), Records of the Farmers Home Administration Record Group (RG) 96,National Archives and Records Administration–Pacific Region (San Francisco) (NARA–Pacific Region [SF])

2. Walter J. Stein, California and the Dust Bowl Migration (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1973), p. 8

3. James N. Gregory, American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture in California (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), pp. 11–13.

4. Stein, California and the Dust Bowl Migration, p. 50.

5. Gregory, American Exodus, p. 6.

6. Ibid., pp. 10, 15, 39–41.

7. Literary journalist Sanora Babb's research writings on California migrants, 1938–1939, are available in On the Dirty Plate Trail: Remembering the Dust Bowl Refugee Camps, ed. Douglas Wixson (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007).

8. Stein, California and the Dust Bowl Migration, pp. 20–22.

9. Ibid., p. 77.

10. Ibid. p. 156.

11. John Steinbeck's 1936 "Harvest Gypsies" series in the San Francisco News was republished in book form by Heyday Books in 1988. Like Sanora Babb's field notes, "Harvest Gypsies" contains fact-based depictions of destitute, starving, diseased, and dying California Okie farm migrants and their families that make the plight of the Joads in The Grapes of Wrath seem almost like "a walk in the park."

12. Jackson J. Benson, The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer (New York: Viking Press, 1984; reprinted by Penguin Books, 1990), p. 332.

13. Stein, California and the Dust Bowl Migration, p. 77.

14. Robert DeMott, introduction to Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath as republished by Penguin Books in 2006, p. xxxii.

15. Elaine Steinbeck and Robert Wallsten, ed., Steinbeck: A Life in Letters (New York: Viking Press, 1975), p. 158.

16. DeMott, introduction to Steinbeck's Working Days: The Journals of the Grapes of Wrath (New York: Viking Press, 1989), pp. xliii, lv.

17. Steinbeck: A Life in Letters, ed. Elaine Steinbeck and Robert Wallsetn (New York: Viking Press), p. 132.

18. Susan Shillinglaw, A Journey into Steinbeck's California (Berkeley CA, Roaring Forties Press, 2006) p. 157. See also Rick Wartzman, Obscene in the Extreme: The Burning and Banning of John Steinbeck's Grapes of Wrath (New York: PublicAffairs, 2008), a book published just following completion of this article.

19. The most thorough Tom Collins biographical account occurs in Jackson J. Benson's "'To Tom Who Lived It:' John Steinbeck and the Man from Weedpatch," Journal of Modern Literature (Spring 1976): 151–210; see also Benson's "The Biographer as Detective" in Looking for Steinbeck's Ghost (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1988), pp. 79–95. The latter also recount Benson's adventures as a pioneering Collins researcher at NARA–Pacific Region (San Francisco). There are Collins-related references as well in Benson's The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer.

20. Application for Employment, June 27, 1937, Official (Federal) Personnel File of Thomas E. Collins, 1922–1942 (Collins OPF), Civilian Personnel, National Personnel Records Center (NPRC), National Archives and Records Administration, St. Louis, MO.

21. Weedpatch Report, Apr. 18 1936, p. 6, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

22. A number of Collins report notes support these points. Some examples can be found in the following: Excerpts (from) Reports of Marysville Migrant Camp (Marysville Camp Excerpts), Thomas Collins 1935, p. 6 (Sept. 7) and p. 15 (Sept. 29), Irving W. Wood Papers, 1934–1937 (Mss 77/111C), Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. Also Weedpatch Reports 1936: Jan. 25, p. 6; Feb. 8, p. 7; Apr. 18, pp. 4–6; and May 9, pp. 6–7; RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF). It should also be noted that Collins's notes regarding praiseworthy federal migrant camper progress on this front are found throughout his reports and far outnumber the above.

23. Marysville Camp Excerpts, exhibit 24, p. 8 (Sept. 14, 1935), box 1/1, folder 12, Bancroft Library.

24. Weedpatch Report, Sept. 19, 1936, p. 18, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

25. Weedpatch Reports, 1936: July 25 & Aug. 1, p. 5, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF). Another interesting instance occurs in Oct. 24, p. 15, where Collins notes that "rugged individualists all their lives, it has taken courage and patience to build up a cooperative community for themselves," as well as the role of "a program of education and tolerance." The history of the camps shows that these types of accomplishments in 1935–1936 with Collins on the scene were not always replicable elsewhere and later. Weedpatch camp memories chronicled by former residents, at the historic camp web site, www.weedpatchcamp.com and in a recent DVD (Huell Howser's, California's Gold, Weedpatch. Dust Bowl Memories) are predominantly positive regarding "togetherness," cooperation, etc.

26. See Weedpatch Reports 1936: Feb. 29, p. 29, on bad conditions at grower camps; Apr. 25, p. 7, and Oct. 24, p. 20, on social workers; and Aug. 8, p. 15, on Hearst, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

27. Gregory (American Exodus, pp. 108–110) remarks on Collins's condescending attitudes toward the migrants while neglecting to account for numerous Collins report instances in which he conveys the opposite. Gregory does recognize that Collins "cared deeply about the people who sought shelter at his camp. Charles J. Shindo, in Dust Bowl Migrants in the American Imagination (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1997) lumps Collins in with other RA/FSA officials covered in his initial chapter on "New Deal Reformers." Shino reports only evidence that aligns with his underlying thesis about urban elitist social manipulators interested mainly in transforming Okies into modernized working class proletarians. A thorough reading of the Collins reports, correspondence, and other documents shows a far more complex, many-sided character whose diverse behaviors were often situational. They depended on "the audience" and what would successfully serve the overall program purpose of migrant (and basic human) well-being. If I had to pick a key word to describe Collins's documented behaviors, it would be "conciliation" rather than "manipulation." The evidence is also that a dominant, deeper core of authentic respect, appreciation for and empathy with the migrants, stemming at least partly from his own non-elitist "rough life, tough times" roots (see Benson), contributed greatly to Collins's successes and his "common/human touch" as a manager.

28. Benson, in "To Tom Who Lived It" (p. 171), quotes comments in this regard from the report of "Special Agent Mensing, Resettlement Administration Investigative Division, 7/15/36," found evidently in headquarters RG 96 files of the National Archives.

29. Marysville Camp Excerpts, p. 2 (Aug. 18, 1935), Bancroft Library.

30. Weedpatch Report, Oct. 24, 1936, p. 15, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

31. Related to Gregory's extensive discussion in chapter 5 of his classic, American Exodus.

32. John Steinbeck, America and Americans and Selected Nonfiction, ed. Susan Shillinglaw and Jackson J. Benson (New York: Viking Press, 2002), p. 215 (Steinbeck's article on "Tom Collins").

33. Weedpatch Report, Feb. 29, 1936, p. 25, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

34. Weedpatch Report, Oct. 24, 1936, p. 10, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

35. Confidential Instructions to Camp Managers, A120734, May 18, 1936, box 1/1, folder 12, Exhibit 15, Irving W. Wood Papers, Bancroft Library. Several drafts of this document carry revisions and additions to the original text that are similar in phrasing and substance to items in earlier Collins reports: for instance, the "Good Neighbor."

36. Weedpatch Report, Sept. 5, 1936, p. 2, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

37. Weedpatch Report, July 11 & 18, 1936, p. 3, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

38. Thomas Dorrance, "Organization, Cooperation, and Administration in the Arvin Migratory Labor Camp," Ex Post Facto, Journal of History Students at San Francisco State University (Fall 2006): 84.

39. Ibid., p. 88.

40. Weedpatch Report, Aug. 22 & 29, 1936, p. 9, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

41. Weedpatch Report, Feb. 22, 1936, p. 8, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

42. One Collins example of many is in Weedpatch Rpts, July 11 & 18 1936, p. 8, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF) (though on the previous page he also uses "putty"). A Steinbeck example occurs at the end of chapter 8, page 84, when Tom Joad describes his "get out of jail" shoes.

43. Descriptions and discussions of this negative stereotyping occur in various Collins reports, for instance during February and April 1936; in Stein, California and the Dust Bowl Migration, pp. 59–63; Gregory, American Exodus, pp. 100–102; and in Jerry Stanley's Children of the Dust Bowl: The True Story of the School at Weedpatch Camp (New York: Crown, 1992), pp. 34–39. And on p. 337 of his True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer, Benson quotes a September 14, 1938, Fresno Bee article in which Dr. Lee Alexander Stone, "a health officer for Madera County," (also cited in Stein) characterizes the (Okie agricultural) migrants as "unmoral, lazy," and "incapable of being absorbed into our civilization." As shown in NARA–Pacific Region (SF) holdings, the latter label was also applied frequently in California against Chinese and Japanese Americans. One example citing the unassimilability of "these sons of Nippon" occurs in the text of a World War II Japanese internment-supporting brief filed in the famous Mitsuye Endo federal case, by then-California Attorney General Earl Warren.

44. A somewhat offbeat example of this variety of negative stereotyping occurs in "Disease Threat Seen in Transient Camps," Oakland Tribune, July 24, 1937, p. 2: "As Mrs. Joan Pratt, county welfare department explains, 'You can't change the habits of primitive people from the southern and mid-western states. You can't force them to bathe or eat vegetables.'"

45. Weedpatch Report, Sept. 5, 1936, p. 4, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

46. Steinbeck: A Life in Letters, pp. 186–187, letters to Carlton A. Sheffield, June 23, 1937, and "many years later" to "his friend Chase Horton."

47. Benson, The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer, pp. 344–345.

48. Weedpatch Report, May 2, 1936, p. 7, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

49. Weedpatch Reports, Sept. 19, 1936, p. 4, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF). Several report items like this indicate that Collins was pleased when campers passed beyond the migrant agricultural cycle for more steady, long-term "mainstream" employment. During his treatment of Collins, Shindo (p. 30) cites an item from an early October 1935 conference speech by Collins titled "The Human Side of Operating a Migrants Camp" (Documents re Migrant Laborers and Establishment of Camps, June–December 1935, box 1 folder 7, Irving W. Wood Papers, Bancroft LIbrary). Shindo writes that "that the goal of creating a stable and docile working force lay beneath the rhetoric of Collins's speech," and in support he quotes Collins's concluding remarks that "they [the migrants, not the camps as indicated by Shindo] will make available for the farmers of the State of California CONTENTED, CLEAN, AND WILLING workers." The Collins statement here is more likely a characteristic, situation-specific ploy to alleviate the considerable early hostility of farmer-grower representatives against the federal camps, by telling them something he thought they would want to hear. Throughout the Collins reports, numerous examples show his interest in migrants becoming savvy upholders of their economic (and human) rights, rather than "a docile (agricultural) working force."

50. Weedpatch Rpt, July 11 & 18, 1936, p. 11, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

51. Weedpatch Report, Feb. 22, 1936, p. 3, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

52. Weedpatch Report, July 25 & Aug. 1, 1936, p. 7, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

53. Weedpatch Report, May 16 & 23, 1936, p. 11, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

54. Marysville Camp Excerpts, p. 16 (Oct. 12, 1935), Bancroft Library.

55. Weedpatch Report, May 2, 1936, p. 15, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

56. Living conditions at ditchbank squatter camps; disease, hunger, and malnourishment; prolonged unemployment and destitution, labor supply/demand, and resultant desperation often reaching back before migration to California; and hostile rejection by mainstream Californians are mentioned as psychotraumatic factors by several authors. The Collins reports contain some general descriptions as well as notes of chronological accounts by migrants and their effects on morale. Examples, concluding with marked improvement at Weedpatch FSA camp, occur in the reports of Apr. 18 (pp. 4–6) and July 25–Aug. 1, 1936 (pp. 12–13). Steinbeck's second article in his nonfiction "Harvest Gypsies" series contains grim, graphic descriptions of squatter camp conditions and psychological trauma. So do some accounts in Sanora Babb's Dirty Plate Trail chapters "Field Notes," "Reportage," and "Dust Bowl Tales." Stein's early chapters describe bad conditions and he also makes occasional notes on psychological effects such as on page 177, where he notes that "migrants reached California in desperate social and economic dislocation. They were vulnerable, defenseless, and disoriented." But even more notable in some respects was how Okie migrants stood up to and eventually overcame such dire situations, partly due to the characteristic creed or "cult of toughness," courage, determination, resilience, honor, and "never give up" perseverance described in Gregory's American Exodus (pp. 145–147).

57. Weedpatch Report, July 25, 1936, p. 5, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

58. Weedpatch Report, Aug. 8 & 15, 1936, pp. 10–12, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

59. Marysville Camp Excerpts p. 4 (Sept. 7, 1935), Bancroft Library.

60. Weedpatch Report, June 27, 1936, p. 5, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

61. Weedpatch Report, Jan. 25, 1936, p. 8, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

62. Weedpatch Report, Feb. 29, 1936, p. 6, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

63. Weedpatch Report, Oct. 17, 1936, p. 12, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

64. Benson, "To Tom Who Lived It," pp. 164, 174.

65. Weedpatch Report, Sept. 12, 1936, p. 7, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

66. An FSA Washington, DC, "Appointment" of February 24, 1937, notifies Collins of his new position, stationed at the Region 9 office in San Francisco. A January 28, 1937, RA Washington DC "Personnel Recommendation" cites designation of Collins from Migrant Camp Manager at Arvin (Weedpatch) to Community Mgr. at Large, San Francisco, effective March 1. However, it cites the "Reasons for Action" as "to have him on call for field supervision and ready to go to Brawley (a new federal camp being established) as soon as construction starts there." An undated U.S. Civil Service Commission "Classification Sheet" likely originated in January 1937 describes Collins's "Community Manager at Large" position under the RA Region 9 "Assistant Regional Director in Charge of Management Division. It makes Collins "available to contact Public Health, Education and other officials in or near Brawley, Coachella, Shafter, Kingsbury, Ceres, Winters, Gridley, and Healdsburg, or in or near any other location for new camps selected or to be selected, and to be ready on short notice to enter into the organization and management of any new camp, as ordered." All in the Collins OPF, NPRC.

67. Memo from NCPCM to Ann. M. Campbell, Chief, Archives Branch, San Francisco Federal Records Center; summary of "biographical information on Thomas Collins and Oscar H. Lipps," Oct. 20, 1972, Collins OPF, NPRC. It abstracts his employment history with RA/FSA. This 1972 document may have resulted from a request by Mrs. Campbell on behalf of Jackson J. Benson during his research visits to NA-SF, then located in San Francisco.

68. Benson, The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer, p. 410.

69. Firebaugh Herald, Oct. 10 and 19, 1941, issues, both p. 1, Migratory Labor Camp Newspapers, 1937–1942, FSA Region IX Office, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF). See also the discussion in Stein, California and the Dust Bowl Migration, pp. 176–177.

70. Tulare Migratory Labor Camp, file code 163-01, 7-1-41, Coded (Migrant Labor) Camp Administrative Files, 1933–1945, box 51, RR-CF-31, FSA Region IX Office, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

71. Weedpatch Report, Dec. 26, 1936, p. 5, RG 96, NARA–Pacific Region (SF).

Further Notes on Sources

As promised, a table of more than 40 correlated "item links" between subjects, events, etc. in The Grapes of Wrath and the RA/FSA records of Arvin/Weedpatch camp, mostly in the Tom Collins reports, accompanies this footnoted online Prologue version of "Archival Vintages for The Grapes of Wrath." While these are only correlations, the overwhelming likelihood is that at least some records/reports items contributed directly to the novel.

The Records of the Farmers Home Administration (Record Group 96) at the National Archives–Pacific Region (San Francisco) contain records of the Farm Security Administration (1937–1946) and of the Resettlement Administration 1935–1937. FSA/RA's Region IX Office in Berkeley/San Francisco compiled Coded (Migrant Labor) Camp Administrative Files, 1933–1945, arranged by migrant camp code and thereunder by subject file code. Arvin (Weedpatch) code 918-01 includes the Weekly Narrative Reports of Tom Collins, 1935–1936.

Misapplications of federal field office records management, usually due to ignorance, were common during the 1940s through 1960s. In the past, federal records of FSA/RA regional officials were donated to the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley (in violation of the Federal Records Act), where they remain today. The collections of federal records researched there for this article include the Harry Everett Drobish Papers, 1917–1954, BANC MSS C-B 529; the Ralph W. Hollenberg collection of materials relating to the Farm Security Administration, Region IX, 1924–1949, BANC MSS C-R 1 Series 2; and the Irving W. Wood Papers, 1934–1937, Mss 77/111C. Also researched were papers on UC Berkeley Professor Paul Schuster Taylor, Papers, 1660–1997, Mss 84/38 c.

Negative "racial-cultural" stereotypes of the California Okie migrants appeared in the texts of numerous newspaper articles during the Depression. A number were accessed as background for this article (see note 43 for an example).

The author thanks Professor Susan Shillinglaw and the Martha Heasley Cox Steinbeck Center, both at San Jose State University, for their help and tips on good "Tom Collins" sources. Thanks also to Susan Snyder, Head of Public Services, Bancroft Library.

In addition to the Cox Steinbeck Center, other wonderful Steinbeck study resources in the San Francisco Bay Area include the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas and the John Steinbeck Collections at Stanford University's Green Library. It should also be noted that the Weedpatch Migrant Labor Camp ( www.weedpatchcamp.com) is today listed in both the National Register of Historic Places and the California Register of Historical Resources. Simultaneously, the old buildings are incorporated within the Sunset Labor Camp operated by Kern County, which continues to house migrant workers from April to September.

Sanora Babb's On the Dirty Plate Trail: Remembering the Dust Bowl Refugee Camps includes field notes that she wrote while in California's migrant labor camps as well as published articles and short stories about the migrant workers. The book also reproduces photographs of the people at the camps taken by Sanora's sister Dorothy Babb. Sanora Babb's California migrants novel Whose Names Are Unknown, eclipsed by The Grapes of Wrath in 1939, was finally published in 2004.

Three Tom Collins–related works by Jackson J. Benson are " 'To Tom Who Lived It:' John Steinbeck and the Man from Weedpatch," Journal of Modern Literature (Spring 1976); Looking for Steinbeck's Ghost (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1988); and The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer (New York: Viking Press, 1984; reprinted by Penguin Books, 1990).

Other secondary works consulted were Thomas Dorrance, "Organization, Cooperation, and Administration in the Arvin Migratory Labor Camp," Ex Post Facto, Journal of History Students at San Francisco State University (Fall 2006); Thomas Fensch, ed., Conversations with John Steinbeck (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1988); James N. Gregory, American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture in California (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989); Susan Shillinglaw, A Journey into Steinbeck's California (Berkeley, CA: Roaring Forties Press 2006); Charles J. Shindo, Dust Bowl Migrants in the American Imagination (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1997); and Jerry Stanley, Children of the Dust Bowl: the True Story of the School at Weedpatch Camp (New York: Crown, 1992).

Walter J. Stein's California and the Dust Bowl Migration (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1973) is the initial classic history in the field. Some of the federal records sources quoted by Stein, then in agency custody and stored at the Federal Records Center in San Francisco, were later destroyed due to bad federal records disposition applications. Others survived to become part of National Archives-Pacific Region (San Francisco) holdings.

Regarding the continuing Grapes of Wrath controversies, Gregory's American Exodus, a more recent historical classic, notes (p. 111) how many involved in the larger "Dust Bowl migration" resented Steinbeck and his portrayals of the Joads and other destitute Okies in the novel for contributing to "some of the unfortunate images already associated with newcomers from the that region" by "falling into the trap of pre-modernism" and crafting "a portrait that many former Dust Bowl migrants have long regarded as demeaning." Unfortunately, heavy reliance on sustained first-hand observation and fact-based materials, such as the records described in this article, failed to save Steinbeck from this fate. Careful readings of both The Grapes of Wrath and the Tom Collins reports also show that neither author purposed to convey that all contemporary California newcomers from the "Okie states" were "ignorant dirt farmers." But it is irrefutable fact, not to be swept under the historical rug, that there were some "Okie migrants" just as described by both Steinbeck and Collins, who also portrayed the human character they exhibited as predominantly and fundamentally fine—even heroic during incredible historic economic and social adversities.

These fact-based portraits, incorporating both the underlying character of these particular people just as described, and the historic adversities they faced and dealt with, confer a value on both The Grapes of Wrath and the Collins reports that is and should be unforgettable. It is also important to neither forget nor downplay the harrowing historical reality of the crisis faced by thousands of destitute 1930s California Okie agricultural migrants.

The edition of John Steinbeck's Grapes of Wrath used by this author was that published by Penguin Books in 2006, with introduction and notes by Robert DeMott.

In addition, the author consulted Steinbeck's America and Americans and Selected Nonfiction, ed. Susan Shillinglaw and Jackson J. Benson (New York: Viking Press, 2002; orig. publ. 1966); The Harvest Gypsies (Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books, 1988; orig. publ. 1936); In Dubious Battle (New York: Covici-Friede Inc., 1936); Working Days: The Journals of the Grapes of Wrath, ed. Robert DeMott (New York: Viking Press, 1989); and Steinbeck: A Life in Letters, ed. Elaine Steinbeck and Robert Wallsten (New York: Viking Press, 1975).

Just after completion of this article, a new work about the Grapes of Wrath post-publication controversy has appeared: Rick Wartzman, Obscene in the Extreme: The Burning and Banning of John Steinbeck's Grapes of Wrath, (New York: PublicAffairs, 2008). An interesting new subject-related DVD is Sights and Sounds of the FSA, 1935–1943, produced by the Pare Lorentz Film Center of NARA's Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum.