A Final Appeal to Capitol Hill

The U.S. House's Accompanying Papers File, 1865–1903

Spring 2007, Vol. 39, No. 1 | Genealogy Notes

By John P. Deeben

Widow Sarah Maynard of Pike County, Kentucky found herself in a quandary. Her husband, Thomas Maynard, died on October 2, 1864, while serving as a civilian in the U.S. military during the Civil War. Several months before his death, Thomas had been recruited by Col. George W. Gallup of the 14th Kentucky Volunteer Infantry as a "secret service man" to watch and report the movements of roving Confederate guerrillas in eastern Kentucky. Sometime later, Gallup authorized Maynard to raise a company of men for the 39th Kentucky Mounted Infantry. While recruiting volunteers along the West Virginia border, Maynard fell into enemy hands near Peach Orchard, Kentucky. The rebels carried him across the border to Wayne County, West Virginia, where they promptly executed him. As witnesses later attested, when Sarah Maynard traveled to Wayne County to retrieve her husband's body, she discovered him "shot through the breast apparently with a musket ball."1

After the war, Sarah attempted to apply for a widow's military pension on January 10, 1867. After considering the application for some time, the Pension Bureau rejected Sarah's claim on September 19, 1871. The grounds for rejection cited the apparent lack of proof that Thomas Maynard had ever served in the U.S. military or that he died while in the line of duty. A statement from Frank Wolford, adjutant general of Kentucky, bluntly asserted: "There is no evidence on file in this office of the enrollment, muster, service, duty, and cause of death of Thomas Maynard, who is alleged to have been a captain recruiting in 1864 for the State of Kentucky."2 A report from the Adjutant General's Office in Washington, D.C., likewise failed to locate Thomas Maynard among the list of known recruiting officers in Kentucky.

Undaunted, Sarah immediately turned to the U.S. Congress for help. She submitted a petition to the House of Representatives that outlined her needy circumstances as well as her futile attempt to obtain a pension. To underscore the fact that she "was left very poor and had a large family to support," Sarah provided a complete list of her eight children, including Richard K. (b. May 15, 1848), Elizabeth (b. October 19, 1849), Vicey (b. July 27, 1851), Nancy J. (b. June 17, 1853), Caroline (b. February 5, 1855), Moses (b. December 23, 1856), Jacob (b. May 1, 1859), and Amey (b. May 4, 1861). That evidence, together with testimony from Colonel Gallup asserting Maynard's employment as a secret scout and recruiting agent, swayed the opinion of the Committee on Invalid Pensions, to whom Sarah's petition had been referred. On April 24, 1872, the committee recommended passage of private bill H.R. 2550 to grant Maynard a pension, although the Senate subsequently sided with the opinion of the Pension Office and rejected the bill on February 6, 1873.3

Sarah Maynard's efforts to obtain compensation through the process of petitioning Congress for a private claim, and the useful family evidence contained therein, highlight the value of private claims for genealogical research. Since the formation of the federal government in 1789, Americans regularly petitioned Congress regarding any private or public matter. Congress received and filed these claims in a variety of ways. From 1865 to 1903, the House of Representatives organized many private claims into a separate body of records called the Accompanying Papers File. Because it is a distinct series, the Accompanying Papers File represents perhaps one of the most useful and readily accessible segments of congressional records that reflect in microcosm the complete spectrum of private claims as well as their genealogical value.

Nature and Arrangement of Private Claims

From 1789 to 1946 many Americans used Congress as the final arbiter to obtain justice or recompense for alleged grievances after exhausting all other legal and administrative options. The first amendment of the U.S. Constitution guaranteed this right to petition, while Article I, section 8, authorized Congress to adjudicate and settle any such claims against the United States.4 Claims often involved expressions of opinion on public policies in the form of a memorial. More typically they requested, in the form of a petition, some type of compensation for alleged personal or financial injury that resulted from government actions. Some claims also sought congressional sponsorship (including funding) of a private cause or enterprise. Monetary redress usually included relief from repaying certain debts, exemption from statutory provisions, or damages for negligent acts committed by the government.5

To cope with the ever-increasing volume of private claims, the Senate and House of Representatives created 14 different standing committees between 1794 and 1946. Both chambers initially established a generic Committee on Claims—the House in 1794 and the Senate in 1816—to deal with all types of private petitions. The House created a more specialized Committee on Private Land Claims in 1813, followed by a similar committee in the Senate in 1826. Realizing that the committee format allowed small quorums of members to develop an ongoing expertise in private legislation, the House over time formed eight additional committees to deal specifically with pensions and war-related compensation, including:

- Pensions and Revolutionary War Claims (1813–1825)

- Revolutionary Pensions (1825)

- Military Pensions (1825–1831)

- Revolutionary Claims (1825–1873)

- Revolutionary Pensions (1831–1880)

- Invalid Pensions (1831–1946)

- War Claims (1873–1946)

- Pensions (1880–1946)

The Senate also maintained a Committee on Pensions from 1816 to 1946 as well as a Committee on Revolutionary Claims from 1832 to 1921. The House Committee on the Judiciary, established in 1813, also dealt with a variety of claims against the federal government. The Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946, however, eliminated all claims committees and transferred responsibility for remaining private claims to the Judiciary Committee of each house.6

Initially, Congress filed early claims among the papers of the House or Senate committee that reviewed them or in a related series of petitions, memorials, resolutions of state legislatures, and other associated documents referred to specific committees. From 1865 to 1903 the House of Representatives arranged private claims into an artificial series called the Accompanying Papers File. (The Senate maintained a similar series from 1887 to 1901 called the Supporting Papers File.) Other claims still appeared among the files of petitions and memorials, depending on the way each petition worked its way through the administrative bureaucracy of Congress. After 1903, however, Congress organized all private claims into a more systematic scheme of bill files and related records, called Papers Accompanying Specific Bills and Resolutions, arranged numerically by legislative bill number.7

In these various filing schemes from 1789 to 1903, Congress generally arranged claims alphabetically by the name of the claimant, but sometimes also by subject matter. Particularly in the Accompanying Papers File, numerous subject files appear, such as Bridges, Ships, Citizenship, Harbors, Rivers, Pensions, and Indian Affairs. For the most part they contain miscellaneous claims submitted by organizations or groups of citizens rather than individuals. More common subject files also relate to individual states and include petitions and memorials submitted by state legislatures and communities. The file for Pennsylvania from the 43rd Congress in the Accompanying Papers, for example, holds petitions from the citizens of Erie concerning improvements to their harbor, a request from bank officials to reimburse the Columbia National Bank of Pennsylvania for the destruction of the Columbia Bridge during the Civil War, and a remonstrance from concerned citizens against the removal of the U.S. Naval Asylum from Philadelphia to Annapolis.8

Types of Private Claims

Private claims covered the gamut of personal issues and topics, and the Accompanying Papers File reflects a revealing cross-section. Requests for military pensions obviously composed the most prevalent claim. A survey of the files in the Accompanying Papers covering Reconstruction (1865–1877) shows that almost half (4,259 claims, 42 percent) of the 10,136 claims submitted to the House of Representatives from the 39th to 44th Congresses dealt with pensions for military service. The vast majority of those claims, not surprisingly, related to service in the Civil War (2,995 claims, 70 percent). The second largest group comprised surviving veterans or dependents of the War of 1812 (552 claims, 13 percent), followed by those of the Mexican War (125 claims, 3 percent), the Revolutionary War (99 claims, 2 percent), and the various Indian wars of the early to mid-19th century (54 claims, 1 percent), including one veteran of the Barbary War of 1805 as well as one claim from the Mormon Expedition of 1857–1858. The remaining 10 percent, or 434 claims, covered pension requests for miscellaneous or undetermined peacetime service in the Regular Army.9

Most citizens typically submitted pension claims to Congress because they failed to obtain benefits through the regular application process to the Bureau of Pensions. As in the case of Sarah Maynard, rejected applications usually involved a lack of adequate documentation to verify a veteran's service record, the failure of the applicant to prove disabilities stemmed directly from active duty, or ignorance regarding the filing deadlines. Widows frequently proved unfamiliar with the existing pension laws, often failing to prove a legal relationship to a deceased veteran or filing for benefits after remarrying, which negated their claim. In these instances, people turned to Congress to receive justice, although many, like Sarah Maynard, ultimately failed to receive benefits.

Civil War–related indemnity claims comprise another significant portion of the Accompanying Papers, although a small handful of petitions sought reparations from the War of 1812 as well. The Reconstruction-era sampling contained 1,265 files (12.5 percent) of this type of compensation. War-related claims dealt not only with real estate, personal property, livestock, and crops destroyed or confiscated by Union or Confederate troops during the war, but also financial losses resulting from wartime military contracts for supplies such as quartermaster goods, commissary stores, or manufactured military items. Other claims sought reimbursement for services as military surgeons, chaplains, nurses, recruiting agents, and spies, or just personal aid and comfort provided to Union refugees and prisoners of war.

Typical is the claim for property damages from William Jewell College. On two occasions during the Civil War, Federal troops occupied the college campus at Liberty, Clay County, Missouri. Following the battle of Blue Mills on September 17, 1861, Union soldiers appropriated the college building as a hospital for approximately 60 wounded men. In August 1862 the Fifth Cavalry, Missouri State Militia, again occupied the college grounds in response to Confederate activity at Independence in nearby Jackson County. On both occasions, according to college trustee O. P. Moss, "it was physically impossible for the Trustees of the college to exercise any control over the college property, real or personal." Resulting damage, estimated at $12,000, included broken windows and furniture; the loss of valuable books, a mineral collection, maps, manuscripts, and a philosophical apparatus; and disfigurement of the campus grounds caused by the construction of trenches and other fortifications.10

In 1874 the trustees submitted a petition for reimbursement, along with a supporting petition from the General Assembly of Missouri, to the House of Representatives. Requesting Missouri Congressman Abram Comingo to sponsor their claim, the trustees noted that "Institutions like William Jewell College which depend for their prosperity, yes life, upon private liberality, need far more the assistance of the General Government in cases like this than [other state-funded] colleges or educational foundations."11 Comingo introduced private bill H.R. 3460 for the relief of William Jewell College on May 25, 1874. The legislation was read twice on the House floor and then referred to the Committee on War Claims for consideration. Unfortunately, the records do not indicate any subsequent action or a resolution to the claim.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, claims seeking relief from court-martial sentences and penalties imposed during the war became prevalent as well. Documentation for 130 such claims appear in the Accompanying Papers from 1865 to 1877. Most of these claims involved private soldiers who petitioned Congress to overturn convictions for desertion or absence without leave and to grant honorable discharges. The underlying motivation for such relief involved a desire to receive back pay, allowances, and pension benefits. Other claimants sought a reversal of fines and penalties relating to the usual spectrum of officer infractions, such as showing disrespect to superiors, conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman, and submitting false reports and accounts to the government.

Perhaps one of the more unusual court-martial claims involved the petition of Lt. William S. Spriggs of Company H, 116th Ohio Volunteers. In 1875 Spriggs asked Congress to dismiss a wartime conviction and dishonorable discharge for what amounted to an early form of DUI—he had been tried in the aftermath of the Gettysburg campaign for public intoxication while riding a horse. Even though Spriggs readily admitted to an indulgence in alcoholic celebration after the battle—"That I may have sometimes tasted liquor, as every other officer did, during the jollification after our victory at Gettysburg, I do not deny"—he staunchly disavowed it impaired his ability to perform his duty. As Sgt. Maj. James M. Dalzell of the 116th Ohio later attested, "Lt. Spriggs although he may like all the rest of us who could get it, have tasted liquor, was not at any time so rendered unfit for duty, or at any other time."12 According to the House legislative journal, Ohio Congressman Lorenzo Danford introduced two private bills on Spriggs's behalf, one (H.R. 4082) to remove legal disabilities resulting from the conviction, and another (H.R. 4737) to authorize the Secretary of War to issue Spriggs an honorable discharge. Neither bill apparently passed.13

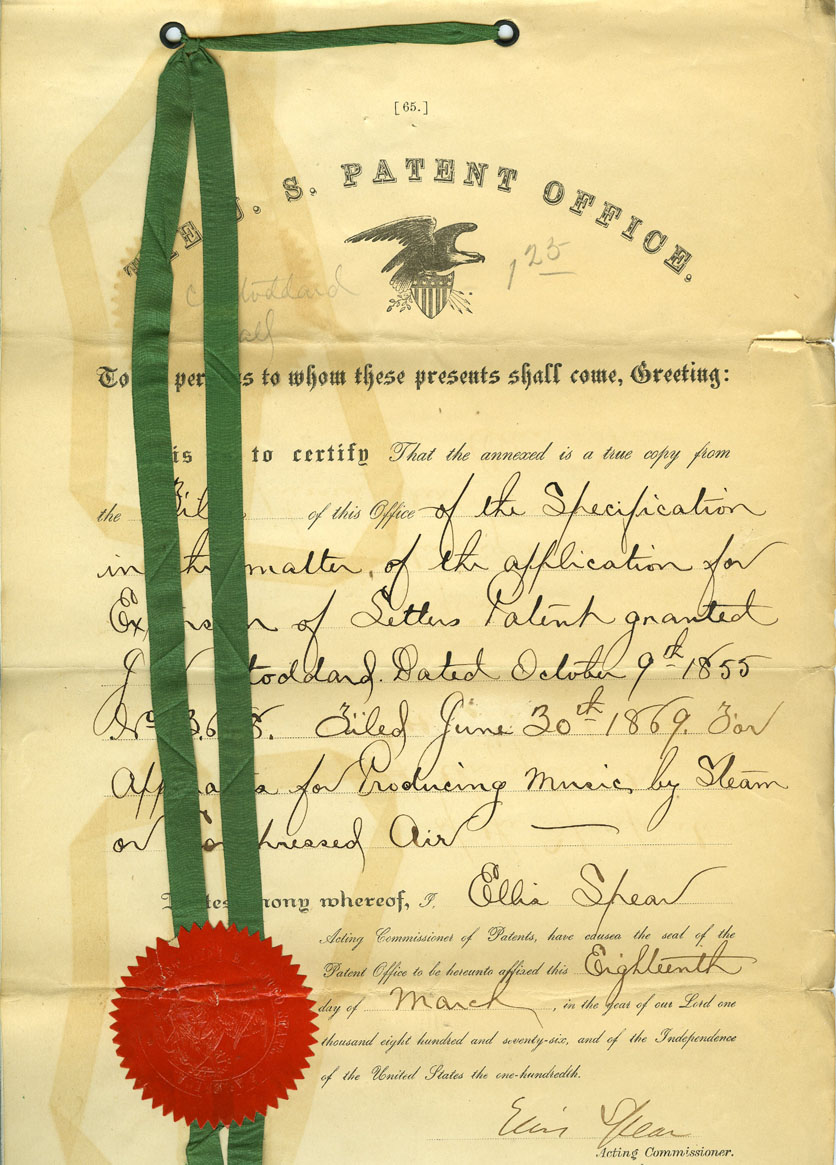

Of course, the great majority of private claims cover an array of miscellaneous but interesting topics. Some of the more common claims sought compensation for various government contracts, including numerous contracts to carry the U.S. mail along remote routes in the western territories, and reimbursement to federal employees for stolen government property. Many of the latter involved robberies committed against post offices, in which case the postmasters petitioned Congress to be relieved from liability for the stolen merchandise. Shipowners salvaging foreign wrecks often asked Congress to issue an American registry or grant permission to change the names of their vessels. Patent claims appeared as well, seeking compensation for patent violations or congressional funding for experiments and trials of new inventions. Musical inventor Joshua C. Stoddard, for example, petitioned Congress in 1876 to renew his patent for "an apparatus for producing music by steam or compressed air," commonly known as the calliope.14

A few interesting claims also relate to specific historical events, such as the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia or property destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Claims from a few nationally known figures appear as well, including Clara Barton's 1866 request for Congress to establish a national system to identify missing soldiers, Dorothea Dix's petition to receive franking privileges, and Confederate general George E. Pickett's 1874 application to remove political disabilities imposed by the 14th amendment.

Records of Genealogical Value

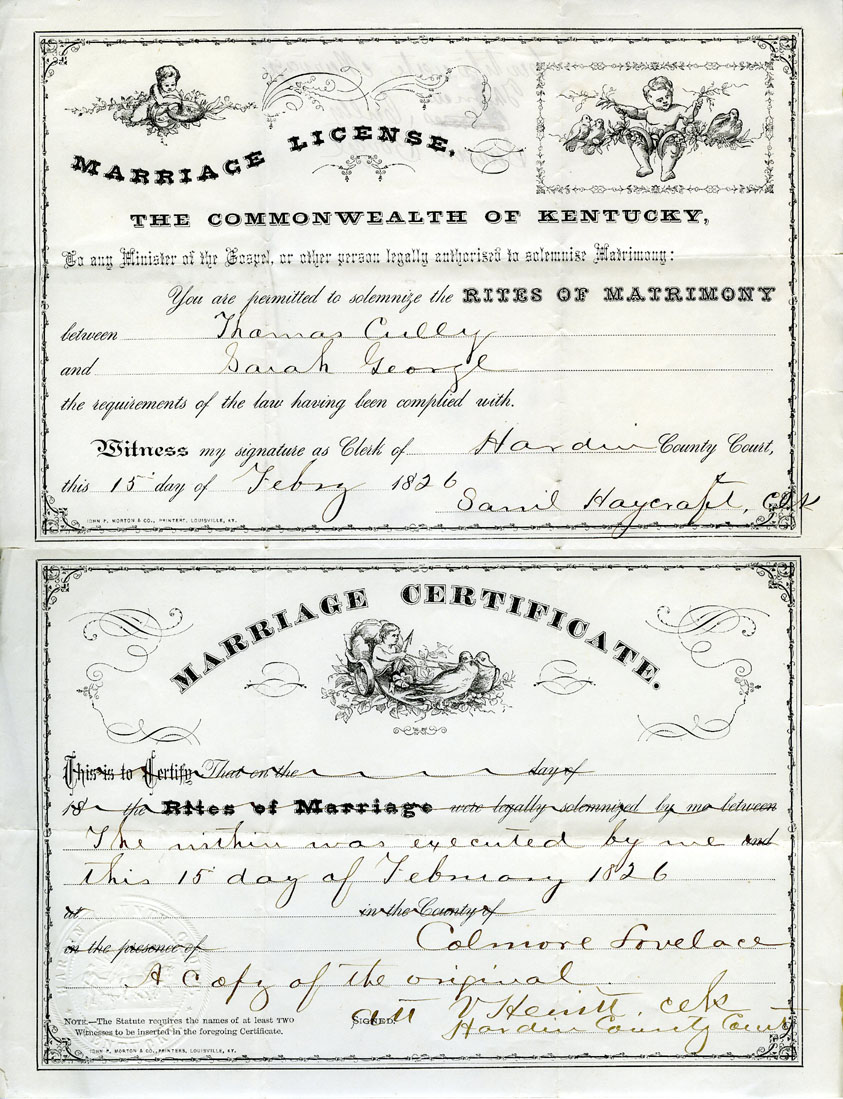

As the broadly diverse nature of these records indicate, congressional private claims document, at their most basic level, the lives and activities—even the hopes and tribulations—of countless ordinary individuals. This essential characteristic in turn highlights the value of private claims as a useful source for family information. Many petitions in the Accompanying Papers provide basic information and vital statistics about the claimants and their families. When aging Revolutionary War widow Sarah P. Cully petitioned Congress in 1872 for a military pension, she identified in her affidavit her birth date (September 12, 1787), her maiden name (George), and the date and location of her marriage to veteran Thomas Cully (February 15, 1826, at Hardin County, Kentucky.)15

The 1876 pension claim of Nancy True, whose three sons perished in the Civil War, likewise identified three generations of her family, including grandfather John Blunt (a major in the Revolutionary War) and parents William and Mary Atkinson; named the residence of her parents (Somerset County, Maine); and verified her maiden name (Atkinson) as well as that of her mother (Blunt). In a manner similar to the Sarah Maynard claim, the 1874 petition of Nathaniel L. Greer of Morrill, Maine, who also lost three sons killed in the Civil War, included a separate listing of his 12 children, along with their dates of birth, as evidence of his needy circumstances.16

Personal and family records appear most prevalently in the pension-related claims because of the need for a widow and dependents to document their relationship to a deceased soldier. The claim of Mary E. Wainwright, whose husband Britton died while serving with Kunkle's Company, Seventh Indiana Legion (Home Guards) during the Civil War, included a notarized copy of their marriage record from the probate court of Hamilton County, Ohio. The record identified their wedding date (May 1, 1847), Mary's maiden name (Darby), and the name of the presiding minister (Rev. James H. Perkins). Sarah Cully's claim held a similar copy of her marriage license and certificate, signed by the clerk of the Hardin County Court. The 1873 pension claim of Annie M. Wright of Chelsea, Massachusetts, whose late husband William served in Company H, First Massachusetts Infantry, contained not only a notarized copy of their marriage record but also a death certificate for William. The certificate, copied from the Chelsea Registry of Deaths, identified William's cause of death (consumption) as well as his occupation (varnisher) and the names of his parents (Peter and Ellen Wright.)17

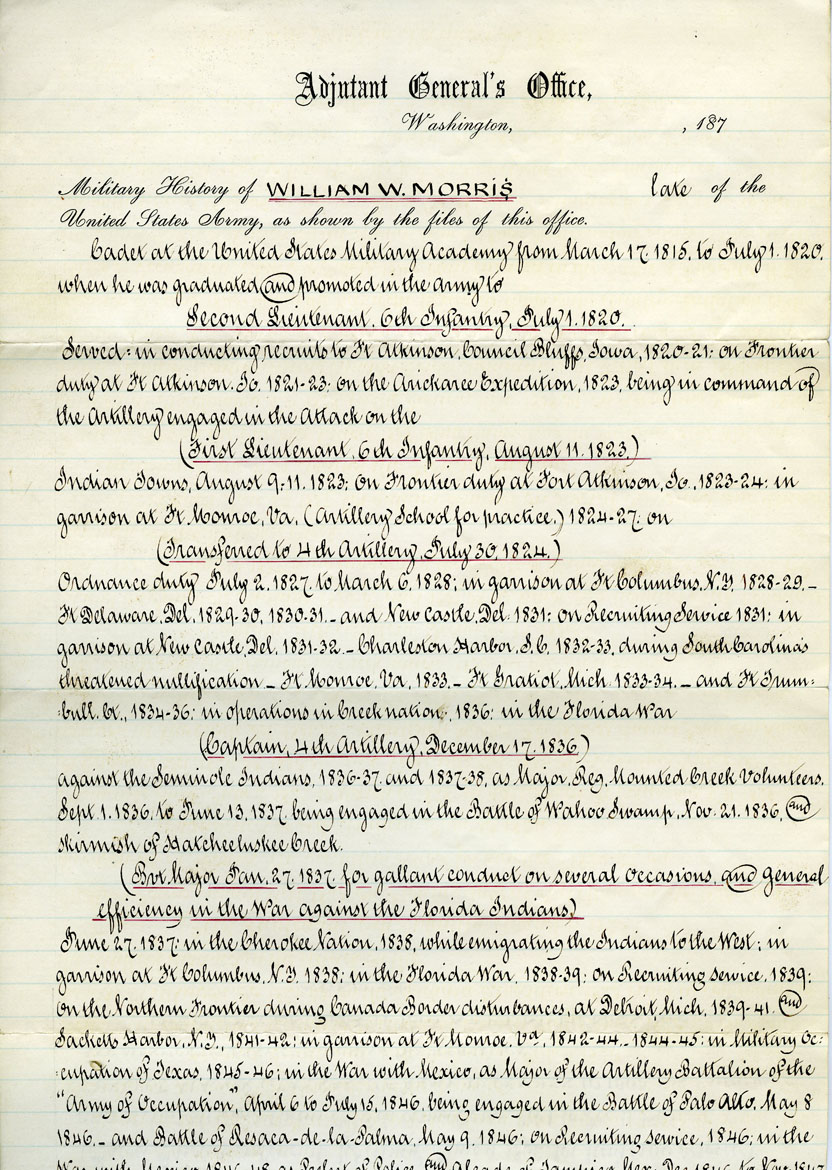

Pension claimants frequently submitted important evidence of military service, including narratives as well as original commissions, enlistment papers, and discharge certificates. A very descriptive military history accompanied the pension claim of Mary A. Morris, whose husband, Gen. William W. Morris, served in the U.S. Army from 1820 until his death in 1865. The handwritten, résumé-like account outlined all the vital events of Morris's career, from his early dates of study at West Point and his various unit assignments and tours of frontier duty, to his final command of the Baltimore harbor defenses during the Civil War, detailing along the way his activities in the Second and Third Seminole Wars and the Mexican War and his promotions from second lieutenant to brevet major general (received the day before his death on December 11, 1865).18

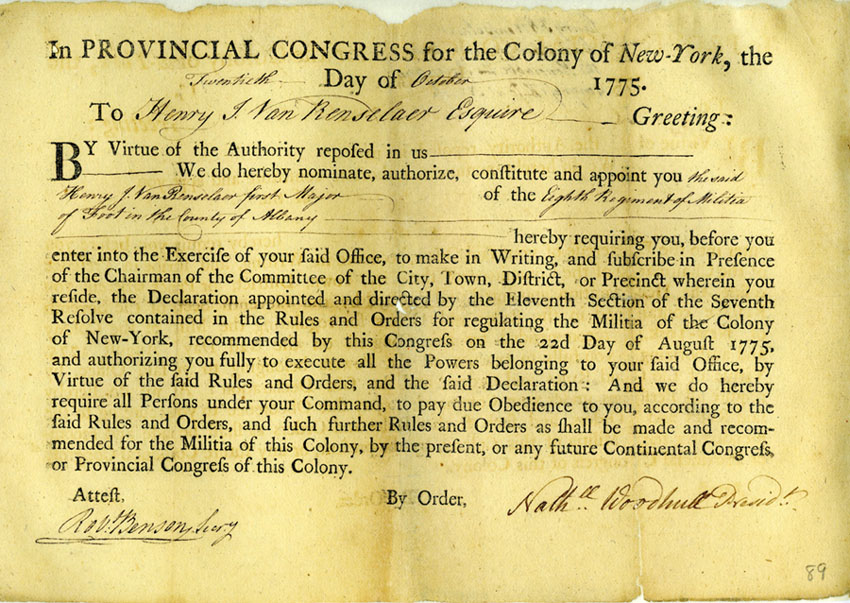

The survivor's pension claim of Margaretta Van Rensselaer, whose father Solomon Van Rensselaer served a distinguished career in the War of 1812, contained handwritten copies of several impressive military appointments, from lieutenant and captain of light dragoons in 1793 and 1795 (both issued by George Washington), to major of cavalry in 1800 (issued by John Adams), as well as an 1819 appointment as major general of New York State militia signed by Governor DeWitt Clinton. Surprisingly, the claim also included a rare colonial commission for another relative, Henry J. Van Rensselaer, who was appointed first major of the Eighth Regiment, Albany County (N.Y.) Militia of Foot on October 20, 1775.19

Other types of vital records sometimes found their way into the Accompanying Papers as well, often through unusual circumstances. The last will and testament of John Elgar of Baltimore, who invented a self-regulating windmill wheel in 1855, later surfaced as an essential piece of evidence in the patent claim of nephew William H. Farquhar. Farquhar inherited the windmill patent when Elgar died in 1858, but the outbreak of the Civil War interrupted efforts to produce the device on a commercial level. Renewed business interest in the windmill after the war caused Farquhar to seek a patent extension in 1869, but the patent expired before the required 90-day renewal notice. He therefore petitioned Congress to grant a patent renewal and submitted a copy of Elgar's will—as well as the original patent letter—as proof of ownership.20 Similarly, Christian Burging, a German-born citizen of Richmond, submitted a war claim to Congress in 1871 for personal property seized by Union forces during the Civil War. Congress rejected Burging's petition because, among other things, he failed to prove he was a naturalized U.S. citizen. In 1876 Burging resubmitted his claim, this time enclosing his naturalization certificate from the Commonwealth of Virginia, which verified his status as a citizen since October 17, 1860.21

Land-related private claims also sporadically contain useful documents such as original deeds or land warrants among their paperwork. As with the Farquhar patent claim, the issue of legal ownership usually influenced the submission of these types of records. In 1873, John and James Scott petitioned Congress to settle an old land claim for a homestead in the former Northwest Territory. The Scotts filed the claim in response to legislation passed in 1872 that offered compensation to former tract holders in the Northwest and Indiana Territories whose land had been confirmed by the territorial governors but later disavowed and sold by the federal government. The paperwork for the claim included the original title, dated February 12, 1799, to the 778-acre tract in St. Clair County, Illinois. The deed contained the signatures of Gen. Arthur St. Clair, governor of the Northwest Territory, and Secretary of the Territory (and future President) William Henry Harrison.22

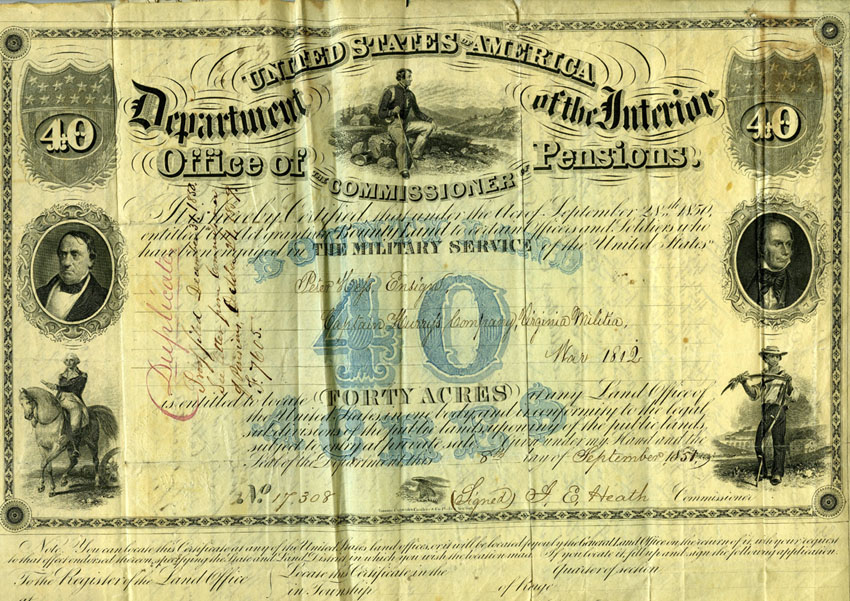

In a similar manner, Frederick Berlin of Upshur County, West Virginia, petitioned Congress in 1866 to validate an old 40-acre bounty-land warrant he acquired in 1859 from the heirs of Peter Hess, a veteran of the War of 1812. According to the General Land Office, the warrant had expired because Hess never applied for the land before he died on December 28, 1850. In his effort to convince Congress to honor the land warrant—which included an affidavit from the postmaster of Buckhannon, Upshur County, verifying that Peter Hess had in fact mailed an application to validate the warrant two days before he died—Berlin also submitted a duplicate but equally decorative copy of the original bounty-land warrant, dated September 8, 1851. The certificate identified Peter Hess's military rank (ensign) and his unit (Hurry's Company, Virginia Militia), while the reverse side contained a handwritten transcript of the legal transfer agreement between Berlin and the Hess heirs, all of whom were identified by name.23

Original photographs of ancestors constitute one final and quite valuable type of document that occasionally turns up in private claims. The reasons photographs appear in these files, especially in the pension-related petitions, remain unclear, except perhaps to provide a human dimension to the claim. Two noteworthy examples in the Accompanying Papers involve the claims of Helen Harrell and Thomas N. McAfrey. In 1874 Helen O'Hara Harrell applied to Congress for a Navy pension following the death on December 16, 1871, of her husband, Capt. Abram Davis Harrell. Her lengthy and sometimes dramatic petition recounted Harrell's naval career, his resulting service-related illnesses, and forced retirement at the close of the Civil War, which left the couple destitute at the time of his death. Affixed to the petition with a black ribbon, probably for added dramatic affect, Helen enclosed a photograph of Captain Harrell, taken in Naples, Italy, in 1859 while he was serving as first lieutenant on the USS Macedonian, the flagship of the U.S. Navy's Mediterranean Squadron. Somewhat ironically, the photograph featured a rather stout and healthy-looking naval officer bedecked in his finest uniform and presentation sword.24

The opposite effect proved true for Thomas N. McAfrey. A veteran of the Mexican War from Tennessee, McAfrey originally received a pension through the normal application process for illnesses contracted during military service. At the outbreak of the Civil War, however, the federal government promptly suspended all benefits for Southern pensioners. In 1876 McAfrey applied to both Congress and the Pension Bureau for a reinstatement of his pension with arrearages to March 4, 1861, the date of his last regular pension payment. To emphasize his sickly circumstances, which included chronic rheumatism, diarrhea, and heart disease, McAfrey enclosed a "photographical exhibit" of himself so that "the Honorable Congress of the United States may see his physical condition."25 His portrait provided compelling evidence, displaying an aged, sickly man with rather gaunt facial features and body frame, clothed in a very loose-fitting suit. A handwritten caption at the bottom of the photograph also identified McAfrey's military rank (lieutenant) and unit (Co. D, 4th Tennessee Infantry) from the "War of 1846."

Access to the Accompanying Papers File

The Accompanying Papers File is part of Record Group 233, Records of the U.S. House of Representatives. (Private claims submitted directly to the Senate likewise make up part of Record Group 46, Records of the U.S. Senate.) All claims records of Congress are in the custody of the Center for Legislative Archives at the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C. A modern guide to House records is Charles E. Schamel et al., Guide to the Records of the United States House of Representatives at the National Archives, 1789–1989. The standard finding aid for the records of the House, however, is Buford Rowland, Handy B. Fant, and Harold E. Hufford, Preliminary Inventory of the Records of the United States House of Representatives, 1789–1946, Preliminary Inventory No. 113 (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Service, 1959.) Listed under the Records of Legislative Proceedings for the 39th to 57th Congresses, each series of the Accompanying Papers File from 1865 to 1903 is identified by separate entry number.26

The U.S. Congressional Serial Set, an ongoing government publication of House and Senate reports issued since 1817, contains the principal published indexes for congressional private claims. Serial Set volumes that cover House claims from the Accompanying Papers File include No. 1574 (32nd to 41st Congresses), No. 2036 (42nd to 46th Congresses), and No. 3268 (47th to 51st Congresses.) The indexes are arranged alphabetically by the claimant's name and identify the nature of the claim, the Congress and session into which the claim was introduced, the committee of referral, the nature and number of any committee reports, the number and disposition of related bills including their dates of passage in both chambers, and the date of presidential approval. A related published index is also available in the Congressional Information Service (CIS) U.S. Serial Set Index, 1789–1969 (Baltimore, MD: Congressional Information Service, 1975.) Recipients of private relief appear under the index heading "Private Relief and Related Actions—Index of Names of Individuals and Organizations."27

In January 2006 the Archives I Research Support Branch produced a descriptive file folder list for the claims from the first six Congresses of the Accompanying Papers File (1865–1877). This enhanced finding aid provides an alphabetical listing of files by container, along with a brief description of the nature of each claim. Staff compiled additional indexes for the numerous pension-related claims from these six Congresses as well. Identifying the name of each claimant or veteran, the type of pension claim, and the Congress under which each claim was filed, the indexes cover the Revolutionary War, War of 1812, Mexican War, Civil War, and various early Indian wars, including the Northwest Indian War of 1794; the First, Second, and Third Seminole Wars; the Black Hawk War of 1831; the Creek Indian War of 1836; the Cherokee Disturbances and Removal of 1836–1839, the Cayuse (Oregon) Indian War of 1848, and the Rogue River Indian War of 1853.

Other prevalent claims that were indexed include Civil War reparations, patent claims, Civil War amnesty and court-martial claims, and Indian depredations. These indexes, in MS-Word document form, are available on CD-ROM in the Microfilm Research Room of the Robert M. Warner Research Center in the National Archives Building. These various finding aids, along with the able assistance of legislative archives reference staff, make the private claims records of the Accompanying Papers File a readily accessible resource for genealogy, unlocking valuable information and often hard-to-find documents to determined family historians.

John P. Deeben is a genealogy archives specialist in the Research Support Branch of the National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. He earned B.A. and M.A. degrees in history from Gettysburg College and Penn State University.

Notes

1. Affidavit of Linza Maynard, Jan. 17, 1871; Sarah Maynard Pension File, No. 140.300; Case Files of Disapproved Pension Applications (Civil War and Later Widows' Originals); Civil War and Later Pension Files, 1861–1942 (Civil War Files); Records Relating to Pension and Bounty-Land Claims, 1773–1942 (Pension and Bounty-Land Claims); Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Record Group (RG) 15; National Archives Building, Washington, DC (NAB).

2. Report of Frank Wolford, Adjutant General of Kentucky, May 14, 1869, ibid.

3. Petition of Sarah Maynard, ibid.; U.S. House Journal, 42nd Congress, 2nd sess., Apr. 24, 1872, p. 750; Senate Report No. 398, 42nd Cong., 3rd sess. (1873).

4. Chris Naylor, "Those Elusive Early Americans: Public Lands and Claims in the American State Papers, 1789–1837," Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration 37 (Summer 2005): 60. A legal explanation of the first amendment and Article I of the U.S. Constitution may be found at the Cornell Law School web site.

5. Charles E. Schamel, "Untapped Resources: Private Claims and Private Legislation in the Records of the U.S. Congress," Prologue 27:1 (Spring 1995): 48.

6. Ibid.; Charles E. Schamel et al., Guide to the Records of the United States House of Representatives at the National Archives, 1789–1989 (1989: House Document No. 100-245, 100th Congress, 2nd sess.), pp. 75–91; Robert W. Coren et al., Guide to the Records of the United States Senate at the National Archives, 1789–1989 (1989: Senate Document No. 100-42, 100th Congress, 2nd sess., Serial 13853), pp. 53–58.

7. Ibid.

8. Pennsylvania File; Accompanying Papers [43A-D1]; Legislative Proceedings, 43rd Cong., RG 233; NAB.

9. Statistics relating to pension claims were derived by the author from a descriptive project conducted by the Archives I Research Support Branch to compile a file folder list of the claims from the first six Congresses in the Accompanying Papers File, including the 39th through 44th Congresses. The folder list included the claimant's name and a brief statement about the nature of the claim.

10. Statement of O. P. Moss, in Proof of Damages, The Trustees of William Jewell College v. The United States, May 12, 1874; Missouri (William Jewell College) File; Accompanying Papers [43A-D1]; Legislative Proceedings; 43rd Cong.; RG 233; NAB.

11. D. C. Allen, Secretary of the Board of Trustees, William Jewell College, to the Hon. Abram Comingo, May 14, 1874, ibid.

12. Petition of William S. Spriggs, Jan. 18, 1875, and affidavit of James M. Dalzell, Jan. 18, 1875; Lt. William S. Spriggs File; Accompanying Papers [44A-D1]; Legislative Proceedings; 44th Cong.; RG 233; NAB.

13. House Journal, 43rd Cong., 2nd sess., Dec. 21, 1874, 89; House Journal, 43rd Cong., 2nd sess., Feb. 16, 1875, p. 475.

14. Joshua C. Stoddard petition for a patent renewal, Mar. 18, 1876; Joshua C. Stoddard File; Accompanying Papers [44A-D1]; Legislative Proceedings; 44th Cong.; RG 233; NAB.

15. Affidavit of Sarah P. Cully, Sept. 14, 1872; Sarah P. Cully File; Accompanying Papers [43A-D1]; Legislative Proceedings; 43rd Cong.; RG 233; NAB.

16. Petition of Nancy True, Jan. 5, 1876; Nancy True File; Accompanying Papers [44A-D1]; Legislative Proceedings; 44th Cong.; RG 233; NAB. List of Nathaniel L. Greer's children, entitled "This is a record of my famuelly," n.d.; Nathaniel L. Greer File; Accompanying Papers [43A-D1]; Legislative Proceedings; 43rd Cong.; RG 233; NAB.

17. Notarized copy of Wainwright marriage license, Jan. 10, 1866; Mary E. Wainwright File; Accompanying Papers [43A-D1]; Legislative Proceedings; 43rd Cong.; RG 233; NAB. Death certificate of William Wright, Jan. 21, 1873; Annie M. Wright File; Accompanying Papers [42A-D1]; Legislative Proceedings; 42nd Cong.; RG 233; NAB.

18. Military career of William W. Morris, compiled by the Adjutant General's Office, n.d.; Mary A. Morris File; Accompanying Papers [42A-D1]; Legislative Proceedings; 42nd Cong.; RG 233; NAB.

19. Handwritten commissions; Margaretta Van Rensselaer File; Accompanying Papers [43A-D1]; Legislative Proceedings; 43rd Cong.; RG 233; NAB.

20. Last will and testament of John Elgar, Jan. 14, 1858; William H. Farquhar File; Accompanying Papers File [41A-D1]; Legislative Proceedings; 41st Cong.; RG 233; NAB.

21. Certificate of citizenship for Christian Burging, Oct. 17, 1860; Christian Burging File; Accompanying Papers [44A-D1]; Legislative Proceedings; 44th Congress; RG 233; NAB.

22. Land Deed, Feb. 12, 1799; John and James Scott File; Accompanying Papers [42A-D1]; Legislative Proceedings; 42nd Cong.; RG 233; NAB.

23. Petition of Frederick Berlin, Mar. 16, 1866; Bounty Land Warrant (copy), dated Sept. 8, 1851; Frederick Berlin File; Accompanying Papers [39A-D1]; Legislative Proceedings; 39th Cong.; RG 233; NAB.

24. Helen O'Hara Harrell File; Accompanying Papers [43A-D1]; Legislative Proceedings; 43rd Cong.; RG 233; NAB.

25. Petition of Thomas N. McAfrey, July 25, 1875; Thomas N. McAfrey File; Accompanying Papers [44A-D1]; Legislative Proceedings; 44th Cong.; RG 233; NAB.

26. Entry numbers for the Accompanying Papers File include: 39th Cong. (E489); 40th Cong. (E502); 41st Cong. (E516); 42nd Cong. (E530); 43rd Cong. (E544); 44th Cong. (E556); 45th Cong. (E570); 46th Cong. (E584); 47th Cong. (E597); 48th Cong. (E608); 49th Cong. (E621); 50th Cong. (E633); 51st Cong. (E646); 52nd Cong. (E659); 53rd Cong. (E670); 54th Cong. (E684); 55th Cong. (E695); 56th Cong. (E706); and 57th Cong. (E717).

27. Naylor, "Those Elusive Early Americans," p. 61.