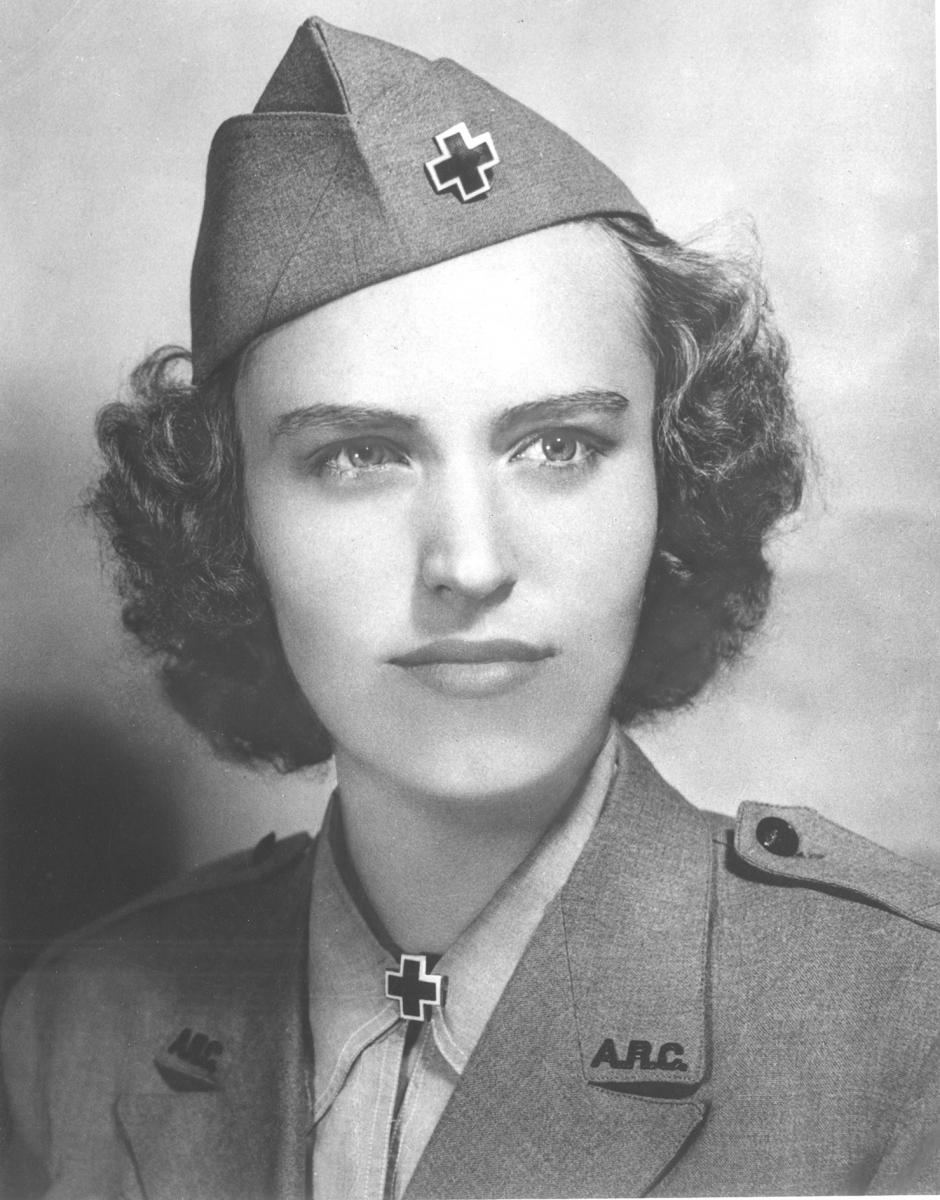

Wearing Lipstick to War

An American Woman in World War II England and France

Fall 2007, Vol. 39, No. 3

By James H. Madison

© 2007 by James H. Madison

The neatly aligned rows of white markers at the Normandy American Cemetery in France encourage visitors to think more carefully about the 9,387 Americans interred in this sacred soil—and about the war they fought. One of those markers, above Omaha Beach, is particularly intriguing. It reads:

American Red Cross

Indiana July 25 1945

Elizabeth Richardson's story opens a window into World War II that enhances and shifts the usual tales of men, foxholes, and bombers. Her life began in Indiana, moved on to college and career years in Wisconsin, and finished with service with the American Red Cross in England and France in 1944 and 1945.

Liz Richardson grew up in Mishawaka, Indiana, an industrial town, 100 miles east of Chicago. After graduation from Mishawaka High School in 1936, she went off to Milwaukee-Downer College. There she embraced the academic and social life of this small liberal arts school. Although she joked lightheartedly about professors and classes, she developed a curiosity that kept her engaged with art, music, literature, and international affairs after graduation.

Along with many of the 1930s generation, Liz believed that America should remain isolated from Europe's tangled quarrels. The Great War of 1914–1918 had taught that lesson. The beginning of another European war in 1939 convinced Liz that "the U.S. will be suckers if they enter it." Pearl Harbor quickly changed her mind. This was now a necessary war, yet she regretted the necessity. "Like a toothache, I hope it ends quickly," she wrote her aunt soon after American entry.

The war didn't end quickly but became instead the most brutal war in human history. Although excited about her new advertising job in Milwaukee, Liz began to follow war news more closely and to worry about friends in uniform. She wanted to do something. In early 1944, with two women she had known in college, she joined the American Red Cross. "We just had to go," one of the friends recalled.

Their choice made good sense. Female applicants for Red Cross postings overseas had to be college graduates, single, and at least 25 years of age. Recruiting teams traveled the country interviewing candidates. Reference letters and physical examinations were essential, but the personal interview was the clincher and, as one official wrote, "often centered around the intangibles of personality." The rigorous selection process accepted only one in six applicants.

Twenty-five-year-old Liz passed her medical examination and whizzed through the all-important personal interview. After six weeks of training in Washington, D.C., she boarded the Queen Elizabeth, one of 15,000 Americans "the Queen" carried across the Atlantic to war in mid-July 1944. A calm voyage placed her in England, a country that had been ravaged by nearly five years of Nazi bombers, food shortages, and the horrors of total war. The English were bearing up in their particular way, sacrificing, fighting hard, and carrying on, but England was a dark and tired place by 1944. The Americans were the great light and hope.

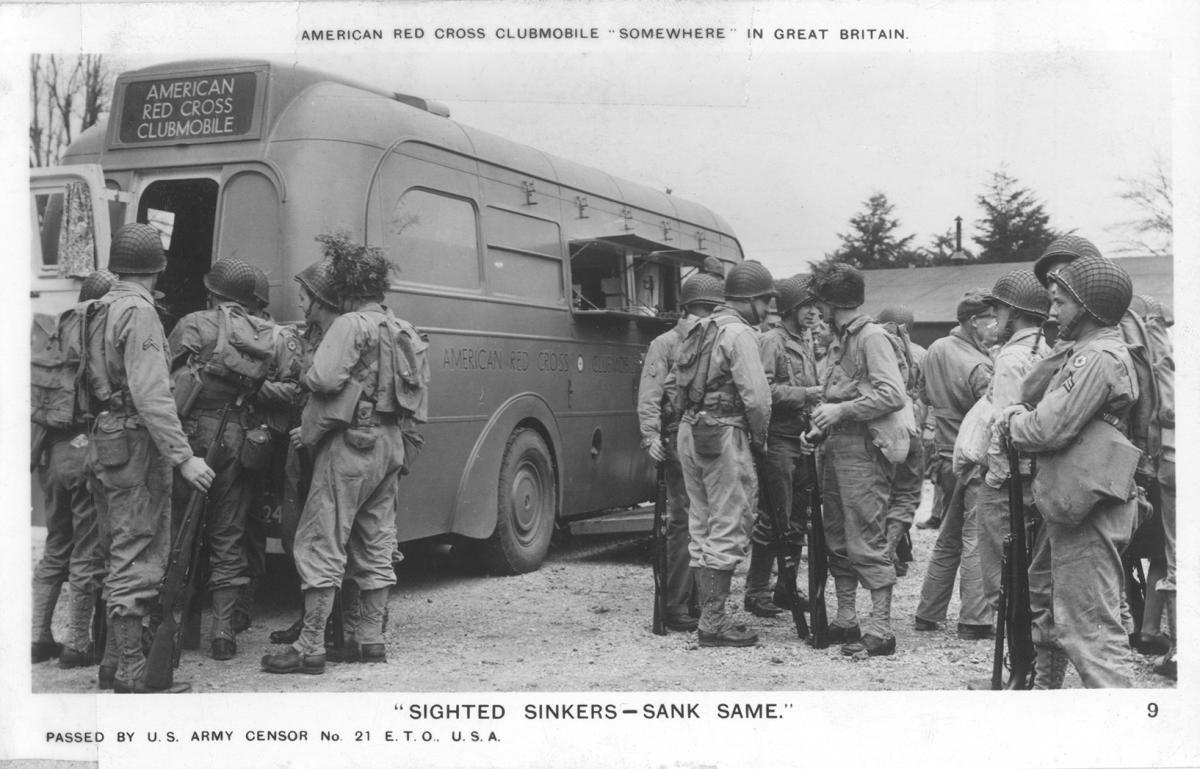

By that summer there were nearly a million Yanks scattered across England, most of them waiting to cross the English Channel and fight the Nazis. Far from home—most for the very first time—they missed family and friends, the comforts of familiar food, music, and fun. Most were very young. Many had not graduated from high school. Many really didn't much like England. They weren't interested in Gothic cathedrals, art museums, tea, or the rural countryside. Even the pubs were often unappealing, with weak, warm beer and early closing hours. They were bored, the food was monotonous, the women too few. And hanging over them was the uncertainty of not knowing when they would go into combat and when they would go home.

The American Red Cross had responsibility for lifting the morale and spirit of these homesick GIs, primarily by operating recreation clubs in the large cities. By 1944, however, Yanks were stationed all over the British Isles, most at a distance from cities with clubs. The Red Cross's response to such massive troop dispersion was the Clubmobile, a single-decker bus fitted with coffee and doughnut-making equipment. Clubmobiles also carried chewing gum, cigarettes, magazines, newspapers, a phonograph, and records. A British driver piloted the large vehicle as it rattled through village streets and down narrow muddy lanes. But the most important contents of each Clubmobile, even more so than coffee and doughnuts, were the three Red Cross women inside, always called "girls." They were the stars of the traveling show. As one Clubmobiler later wrote: "Doughnuts and coffee were our props."

For many GIs in England, the sight of an American woman was so unusual, Liz wrote soon after her arrival, that "you feel sort of like a museum piece—'Hey, look, fellows! A real, live American girl!'" In a letter to a Milwaukee friend, she explained "If you have a club foot, buck teeth, crossed eyes, and a cleft pallette [sic], you can still be Miss Popularity. The main thing is that you're female and speak English."

It wasn't just their small numbers that made Clubmobilers special. All had been carefully and deliberately selected by the Red Cross. They knew the right slang, had the right look, knew how to take and make a wisecrack, and knew how to talk about baseball, Glenn Miller, and apple pie. They encouraged banter. Clubmobiler Eleanor Stevenson explained how they'd yell out to a truckload of GIs, "'Hi, soldier. What's cooking?' and the guys would yell back, 'Chicken! Wanta neck?'" Standing beside their Clubmobile at an isolated, windswept military camp in England, Red Cross women knew how to look at pictures of girlfriends and wives and how to listen to stories, including the sad news from home that ended a romance or told of the death of a loved one. They could join an impromptu jitterbug dance next to the Clubmobile or sing along as their well-worn phonograph record played the same few popular songs from home.

Red Cross women were not sexy, at least not in a provocative sense. Their uniforms had a military style, enhanced often by muddy combat boots and odd bits and pieces of clothing. Life magazine glowingly described a Clubmobile arriving at a camp in England "with a smartly uniformed crew of three girls." More often than not the soiled pants and jackets the women wore in the field to keep warm and dry left them looking bedraggled or, at best, "somewhere between dowdy and glamorous," as Clubmobiler Mary Metcalfe recalled. Sometimes they hadn't had a bath for several days; often they smelled of doughnut grease; always their hands were red and raw.

Yet they avoided the "mannish" or "Amazon woman" stereotypes that invited disdain from 1940s Americans. They usually took time to put on lipstick, nail polish, and perfume. These smart women quickly came to see that such small feminine connections to the girls back home meant worlds to the boys in the field. Clubmobile women could sing slightly bawdy songs, respond to off-color jokes, deflect a sexual advance, and yet remain respectable women the guys loved to be near.

Often they heard wolf whistles, especially when GIs first saw them. They learned, as one wrote in a 1944 issue of Ladies Home Journal, "to get over the embarrassment of walking through lines of men all thoughtfully extending their complimentary whistle. Now, instead of getting red-faced and awkward, we throw back our shoulders, wave and whistle back." As Liz wrote her brother, "How the men refrain from whoopsing when they see us, I don't know, but instead of that, we're treated like Miss America in a Wolf corale [sic]." And she added, "I certainly have improved my stock of evasive tactics. And you should see me jitterbug, with proper, Red Cross decorum, of course."

From the thousands of hours they spent with GIs, Clubmobile women came to know far more about the men and the war than all but the small percentage of those who actually experienced combat. From her Clubmobile base in England, Margaret Gearhart wrote her parents: "Believe me, Mom and Dad, we Red Cross have seen more of this war than anyone—and what we've seen and heard could make an excellent book. We feel the spirit and soul of the war."

Like most Clubmobile volunteers, Liz developed strong feelings for the soldiers. They told her stories not reported in newspapers, tales of combat and brutality, of choices grimly made, of fears and deep regrets—stories that a GI might not write home to a wife or girlfriend, not tell children or grandchildren in the years to come, and sometimes not even confide to a best buddy. "I'm used to the men going over every minute on the line," Liz wrote her parents. After several weeks working with the 82nd Airborne, just returned to England for rest after fighting the Germans for 33 hard days, starting on D-day, she lamented to her parents, "If you only knew what combat does to these boys—not in the physical sense, although that's bad enough—but mentally."

Red Cross women worked hard to make what they did look simple: their Clubmobile arrived at a camp, and soon there were smells of hot coffee and doughnuts, a scent of perfume, a flash of lipstick, a smile, and a cheery "hello, soldier, where you from?"

Liz and her colleagues were not warriors and usually stayed far away from the front lines. The work they did was traditionally defined as "women's": they cooked, cleaned up, and waited on men. Yet these women did essential war service that included demanding physical labor and stressful emotional costs. Their jobs required sophisticated organizational skills and superb interpersonal relations. And they carried out their duties in a foreign culture away from home with limited resources and scant administrative support. Their experience, maturity, and education gave them a self-awareness and understanding of the job they were doing. They saw the surface contradictions between their mundane chores of serving doughnuts and coffee and their college educations and between their image as "girls" and their work as sophisticated and talented women.

The men remembered these young women with their doughnuts and coffee, their laughter and banter, their ears tuned for sounds of GI homesickness and anxiety. From France, in spring 1945, Liz wrote her parents:

we were cruising past some resting troops, when I heard them shouting "Hey, Liz! Hey, Milwaukee!" It was a whole unit that we had known in England and we had a wonderful reunion right there on the road. And yesterday I met one of the cooks who had helped us brew our coffee during that week of the invasion of Holland. It's funny how they remember you and stranger yet how we can remember them after seeing thousands and thousands of faces.

At the Le Havre airport on the morning of July 25, 1945, Elizabeth Richardson jumped into a two-seat military plane to fly to Paris. Near Rouen the plane crashed. Liz and the pilot, Sgt. William R. Miller of the Ninth Air Force, died instantly. She was 27 years old.

Liz Richardson never regretted her choice to go to war. "I consider myself fortunate to be in Clubmobile—can't conceive of anything else," she wrote her parents in September 1944. "It's a rugged and irregular and weird life, but it's wonderful. That is, as wonderful as anything can be under the circumstances." To a best friend from college she had quipped, "Damn glad I have a degree—it helps so much in making doughnuts." And then she added, "I wouldn't trade this for anything else and it has more satisfaction in the doing than anything Auntie has ever done."

Travelers to the American Cemetery in Normandy today see row upon row of war dead. Sometimes there are flowers placed at the base of the marble cross that marks Grave 5, Row 21, Plot A. Nearby, at the new Visitor Center, they can see a blown-up photograph of one American Red Cross volunteer, carrying a heavy coffee urn, smiling, and wearing lipstick.

James H. Madison is Thomas and Kathryn Miller Professor of History at Indiana University, Bloomington. This article is adapted from his book Slinging Doughnuts for the Boys: An American Woman in World War II (Indiana University Press, 2007).

Note on Sources

Elizabeth Richardson's wartime letters, diary, watercolors, and photographs are in the possession of her brother, Charles M. Richardson, Jr. The National Archives at College Park, Maryland, provides substantial primary source material, most important, the Records of the American Red Cross, 1935–1946, Record Group 200. Another major collection is the Hazel Braugh Records Center and Archives of the American Red Cross in Lorton, Virginia. At Harvard University, the American Red Cross Clubmobile Service Collection, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, provides very helpful letters from several Clubmobile women.

The author relied also on interviews with several Clubmobile veterans and numerous published autobiographies, including Marjorie Lee Morgan, ed., The Clubmobile: The ARC in the Storm (St. Petersburg, FL: 1982); Oscar Whitelaw Rexford, ed., Battlestars & Doughnuts: World War II Clubmobile Experiences of Mary Metcalfe Rexford (St. Louis, 1989); and Rosemary Norwalk, Dearest Ones: A True World War II Love Story (New York, 1999). A good web site devoted to Clubmobile history, with some firsthand accounts, is www.clubmobile.org/index.html.

The secondary literature on World War II is immense and growing rapidly. Among books on combat that provide good context for the Clubmobile work are Gerald F. Linderman, The World Within War: America's Combat Experience in World War II (New York, 1997); Peter Schrijvers, The Crash of Ruin: American Combat Soldiers in Europe during World War II (New York, 1998); and Max Hastings, Armageddon: The Battle for Germany 1944–1945 (New York, 2004). The general British context is expertly studied in David Reynolds, Rich Relations: The American Occupation of Britain, 1942–1945 (London, 1995), pp. 242–243. Helpful for France is Harvey Levenstein, We'll Always Have Paris: American Tourists in France since 1930 (Chicago, 2004), and Hilary Footitt, War and Liberation in France: Living with the Liberators (New York, 2004).

Books that help understand men and women in war include Leisa D. Meyer, Creating GI Jane: Sexuality and Power in the Women's Army Corps during World War II (New York, 1996); Christina S. Jarvis, The Male Body at War: American Masculinity during World War II (DeKalb, IL, 2004); and D'Ann Campbell, Women at War with America: Private Lives in a Patriotic Era (Cambridge, MA, 1984). For a very good introduction to wartime correspondence, see Judy Barrett Litoff and David C. Smith, We're in This War, Too: World War II Letters from American Women in Uniform (New York, 1994).

Helpful introductions to the American Red Cross are Foster Rhea Dulles, The American Red Cross: A History (New York, 1950), and George Korson, At His Side (New York, 1945). There is very useful information on the organization's web site at www.redcross.org/museum/history/.