Abner Pratt and Michigan's Honolulu House

Fall 2006, Vol. 38, No. 3

By Peter von Buol

On September 18, 1860, after spending four months in the Hawaiian Islands, the USS Levant, an 18-gun naval vessel, left the port city of Hilo for Panama. Unfortunately, that was the last day anyone ever saw the 23-year-old sailing ship intact or any of its 150 crew members alive. The ship never arrived at its destination, and it now seems it was lost in a violent hurricane that struck the North Pacific in September 1860.

The U.S. Navy conducted a search for the vessel in early 1861, but no trace of the ship or its crew was found at that time. "The disaster must have been so sudden that no time was given to save the lives of those on board by taking to the boats or building a raft," wrote Henry M. Whitney, the former publisher of the Pacific Commercial Advertiser, in 1898.

The Levant had been sent to Hawaii at the request of the State Department. Comdr. William E. Hunt, the ship's captain, had been appointed to serve as a special commissioner to investigate charges of fraud among the U.S. consular service and its employees at the U.S. seamen's hospitals in Hawaii. Hunt had been instructed to pay special attention to the consulates and hospitals in Honolulu and Lahaina.

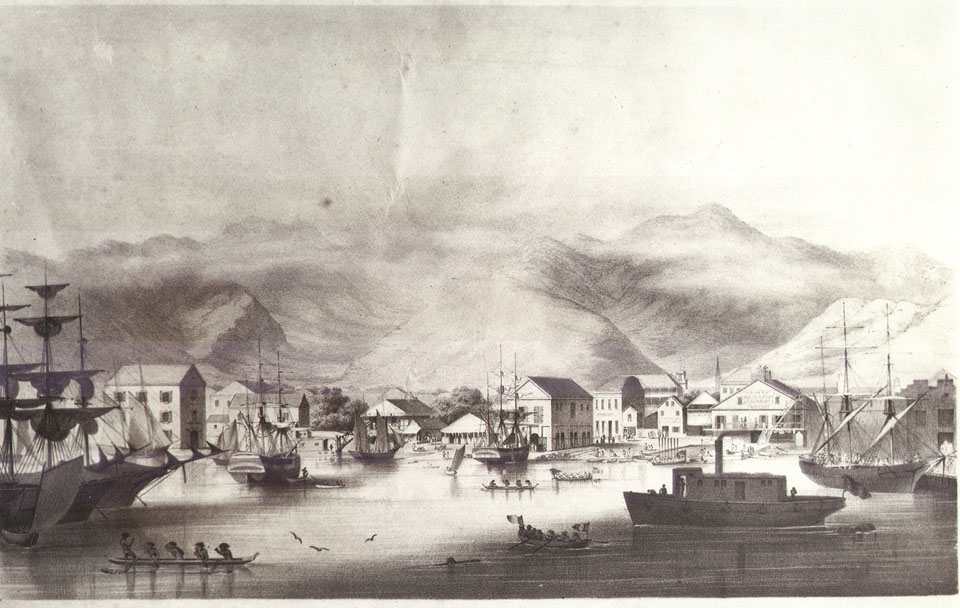

Prior to Hawaii's annexation to the United States in 1898 and long before statehood in 1959, the Pacific archipelago had been an independent nation to which the State Department had sent its representatives. By the mid-1800s, a U.S. consul to Honolulu represented American business interests, and a U.S. commissioner of Hawaii represented American diplomatic interests in the nation's capital. Honolulu was a city of about 11,000 residents, and most lived in homes that resembled those in New England.

In 1860, the U.S. consul at Honolulu was Judge Abner Pratt, a former chief justice of the Michigan Supreme Court. Unfortunately, when Hunt and the Levant arrived in the kingdom, Pratt was no longer in Honolulu. The judge had returned home early due to ill health. He had long suffered from asthma, and the tropical climate had caused his condition to worsen.

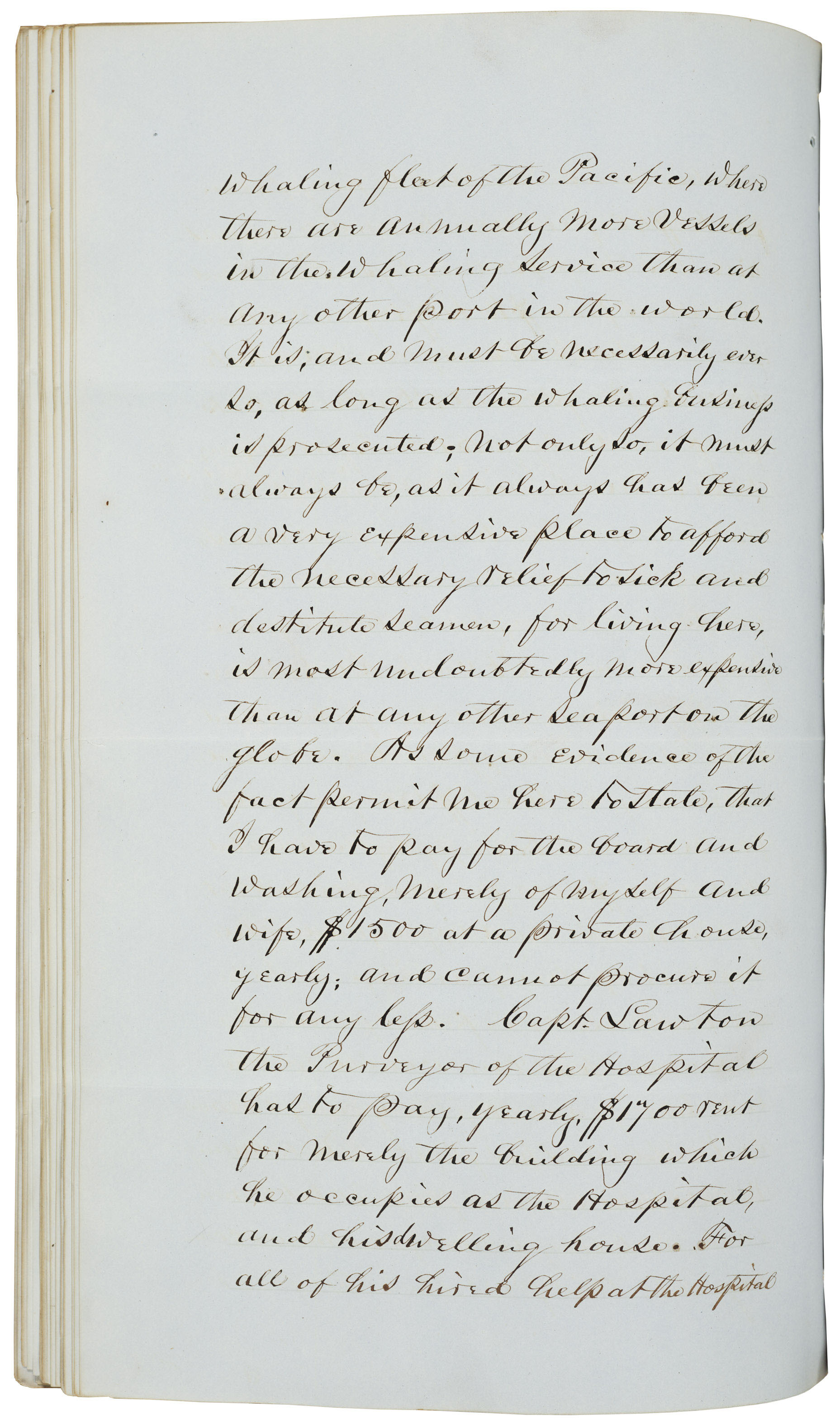

Hunt's inquiry was not the first federal investigation that involved the consular corps in Hawaii. For decades, officials in Washington had been concerned about the Hawaii consuls' steep bills, which exceeded those from all other ports in the world. At first, the unusual claims were attributed to the high cost of living in Hawaii and the high volume of sea traffic from American ships.

In the early 19th century, the State Department did not usually send career civil servants as its agents or consuls overseas. American merchants based overseas often served as the government's official but unpaid representatives. These early American representatives were legally allowed to charge fees for their paperwork in order to support their official positions.

By the mid-19th century, however, consuls were usually political appointees. Pratt had been appointed to serve as U.S. consul to Honolulu in 1857 by President James Buchanan as a reward for the judge's loyal service to the antebellum Democratic Party.

Whaling and the U.S.-Hawaii Connection

Decades prior to Pratt's tenure in the Hawaiian Islands, the first U.S. representative to Hawaii had been the merchant John Coffin Jones. As the U.S. agent, Jones had no diplomatic duties, and it was not until 1843 (after Jones had been replaced) that Congress authorized the posting of a diplomatic representative to serve in the Kingdom of Hawaii. The first American diplomat, George Brown, was given the rank of commissioner by the State Department, and he arrived in October 1843. Shortly afterward, in 1844, the position of agent was elevated to consul.

By the 1850s, both Honolulu and Lahaina, on the island of Maui, had become the busiest ports for American ships sailing in the Pacific Ocean. Hilo, on the Big Island of Hawaii, was another important port.

Most whaling ships regularly sailed between New England and the Sea of Japan off the coast of Asia, then the prime hunting ground for sperm whales. Before the widespread use of petroleum oil, whale oil was the main source of fuel oil for illumination. At the time, it was also the best industrial lubricant for machinery. Sperm oil was considered the finest whale oil and it often sold double or triple the value of other whale oils.

The number of visits from American whaling ships increased dramatically throughout the first half of the 19th century. The first two American whalers arrived in 1819, and just three years later, 60 whale ships anchored in Hawaii. For the next two decades, the ports of Honolulu and Lahaina would experience brisk shipping traffic. On average, both ports had visits from about 100 ships per year.

The American whaling fleet's visits occurred twice a year, from March until May and from October until December. They arrived in Hawaii after an 8,000-mile journey from New England and spent, on average, between three to five years away from their home ports.

The most successful decade for the American whaling fleet based in the Hawaiian Islands was from 1845 to 1855. In 1846, 736 whalers had anchored in the island kingdom, and that figure would never again be equaled. However, the most successful year commercially was 1852, when 373,450 barrels of whale oil were collected.

At the Hawaiian ports, incapacitated or sick sailors and whalers would disembark to recover. It was the duty of a consul or an agent to provide for their care or to send a destitute seaman home to America. The Honolulu consul oversaw the care of nearly 200 seamen in a season.

Acting U.S. consul William Hooper, on December 31, 1844, sent a despatch to Washington, D.C., that gave a legitimate explanation for the high costs he had incurred for the care of sick and disabled American seamen in Hawaii. Hooper explained to the State Department that more work-related injuries had occurred as the American whaling fleet had shifted away from hunting sperm whales and had begun hunting northern right whales. In addition, Hooper said, whalers also suffered more illness due to spending months in the frigid North Pacific and Arctic Oceans.

When U.S. Consul Joel Turrill took over the Honolulu post in 1846, he conducted his own investigation of the high costs associated with the Hawaiian ports. He reported costs at Hawaiian ports had continued to remain high due to the high volume of visits from American whaling ships. In fact, because of its modern standard of medical care and mild climate, Hawaii remained the best place in the Pacific for American sailors and whalers to recover from their injuries and illness.

Expenses for the consuls mounted quickly during the mid-1800s because they were expected to pay any expenses for seamen up front and wait for reimbursement from Washington. The delay between payment and reimbursement strained the pockets of many consuls.

Consuls were also required to finance the room and board for healthy American seamen who waited for either their next assignment or a return home. Consuls were not repaid until the federal government received payment from the owners of the wrecked vessels. Ship owners contributed to a seamen's relief fund that would pay discharged or disabled seamen $12 a month for two or three months, and consuls were to use these wages to pay medical bills.

Corruption within the U.S. Consular Service

The vast sums of money involved in the seamen's fund eventually proved to be too tempting. Some consuls and their employees were suspected of embezzlement and fraud, and in a few cases, suspicion led to federal investigations for graft and corruption.

After Charles Bunker of Massachusetts arrived as U.S. consul to Lahaina in 1850 (which had recently been elevated to a consulate from an agent), costs at the consulate skyrocketed. By 1852, officials at the Treasury Department had become suspicious. The costs to care for seamen at Lahaina were nearly double per person than those in Honolulu, according to Treasury Department auditor S. Pleasonton in a March 24, 1852, letter to the State Department.

Bunker's predecessor's expenses, stated Pleasonton, fell "far short of those of Mr. Bunker, which have increased from upwards of 6,000 dollars to the enormous sum of more than 20,000 dollars a quarter, in clothing, provisions and medicine for destitute seamen. His last quarter's account, rendered to this office, amounts to 20,566 dollars, for the maintenance, as he stated, of 186 seamen, part of whom were maintained for the portion of the quarter only. . . . [T]he Consul in Honolulu charges 11,913.91 dollars for maintaining 191 seamen for that same quarter."

Pleasonton found it particularly odd that Bunker charged every American a daily fee for medical care, even though many under his charge were healthy.

Pleasonton recommended that Luther Severance, the U.S. commissioner to the Hawaiian Kingdom, travel to Lahaina to investigate prices and conditions. Bunker somehow learned of the investigation and left the kingdom in early 1853, before the arrival of federal investigators.

Bunker's scheme was perhaps especially noticeable at the time because he had been compared to the Honolulu-based consul, Elisha Allen, who was probably among the most qualified consuls to have served the American government in Hawaii.

Allen's successor was Benjamin Franklin Angel, who served for just over a year. He had been a recess appointment in 1853 and was ultimately rejected at a Senate confirmation hearing in 1854.

While Angel's receipts and expenses were somewhat modest in comparison to Bunker's, Commissioner David L. Gregg wrote the State Department to express his own suspicions that Angel had profited from his position.

Angel's successor, Darius A. Ogden, served briefly, but he did fill two open positions at the consulate's U.S. Seamen's Hospital in Honolulu. Ogden hired Dr. Charles F. Guillou as the hospital's physician and Dr. George A. Lathrop as the hospital's purveyor. Lathrop served as Ogden's right-hand man and was actually the one in charge of operating the hospital and its expenses.

Under Ogden and Lathrop, consular expenses continued to be high. In two years and nine months, they billed the U.S. Government for more than $86,000.

Michigan Judge Abner Pratt Posted to Hawaii

As Ogden's replacement, President James Buchanan chose Judge Pratt, whose term as chief justice of the Michigan Supreme Court had expired. Pratt had requested a consular position in a mild climate as he suffered from asthma, and he was awarded the position in Honolulu.

Prior to Pratt's arrival in Honolulu in 1857, the federal government had changed how consuls at important posts were compensated. The position of U.S. consul to Honolulu became a salaried position, and Pratt earned $4,000 a year. Also, Pratt was not allowed to retain the administrative fees he had collected on behalf of the government and was not allowed to engage in any private business activities.

Pratt seems to have continued the illegal methods that had been employed by Ogden, Angel, and Lathrop once he assumed control of the Honolulu consulate. Despite the Treasury Department audit that several years earlier had uncovered Bunker's fraudulent practices at Lahaina, safeguards had not been put into place.

The high costs of maintaining the consulates and hospitals in Hawaii were too much for Secretary of State Lewis Cass to ignore in 1859.

On May 16, 1859, the State Department officially asked the secretary of the navy to send a ship to Hawaii. Its captain would be appointed as a special commissioner in order to lead an investigation into the financial discrepancies at the Hawaiian consulates and hospitals. Treasury Secretary Howell Cobb, less than two months earlier, had sent a financial report to the State Department that revealed that expenses from Hawaii during 1857 and 1858 had reached a total of $150,216.40.

On the same date, the U.S. commissioner to Hawaii, James W. Borden, was designated as associate commissioner for the investigation.

As a courtesy, the State Department sent Pratt instructions to provide any assistance necessary to the ship's commanding officer upon his arrival in Honolulu.

Pratt's consular instructions never reached him because he had already left the Hawaiian Islands by the time the memorandum was delivered to the Honolulu consulate. Due to his worsening asthma, Pratt returned to the United States on leave after the winter whaling season ended in January 1860.

On numerous occasions, the State Department asked Pratt at his home in Marshall, Michigan, to return money that had been reported missing.

Frederick L. Hanks, a Honolulu businessman whom Borden had asked to become acting consul, wrote in a November 9, 1860, report:

Mr. Pratt, the late Consul, on his departure for the United States left in the office only the sum of $1,946.63 and carried away with him the sum of $4,326.98, which sum should have properly remained in this office, to be credited, one third to the government, and two thirds to the various seamen upon their application for the same on their departure for the United States. The consequence is, that in a few days, the amount of $1946.63 actually left in the office by Mr. Pratt will have been disbursed, leaving one hundred and thirty seamen who are liable at any moment to become a charge upon this consulate as destitute seamen and to call at this office for their extra pay and will have to be refused in either case, in consequence of Mr. Pratt's unwarrantable and dishonorable conduct.

Hanks also said Pratt had taken with him money that had been deposited at the consulate by seamen who had died. Hawaii did not have a banking system in the mid-1800s, and the sailors often deposited their cash at the consulate while they were patients at the seamen's hospital.

"Pratt carried with him (as an entry upon the books in his own writing states, 'to be deposited in the U.S. Treasury') $41.02 belonging to the Estate of James Huntley, who died in the U.S. Hospital; $314.23 belonging to the Estate of Archibald Macklin who died in the U.S. Hospital; and $139.59 belonging to the estate of Robert Amman, who died in the Sailor's Home [on the] Third [of] May 1859," added Hanks.

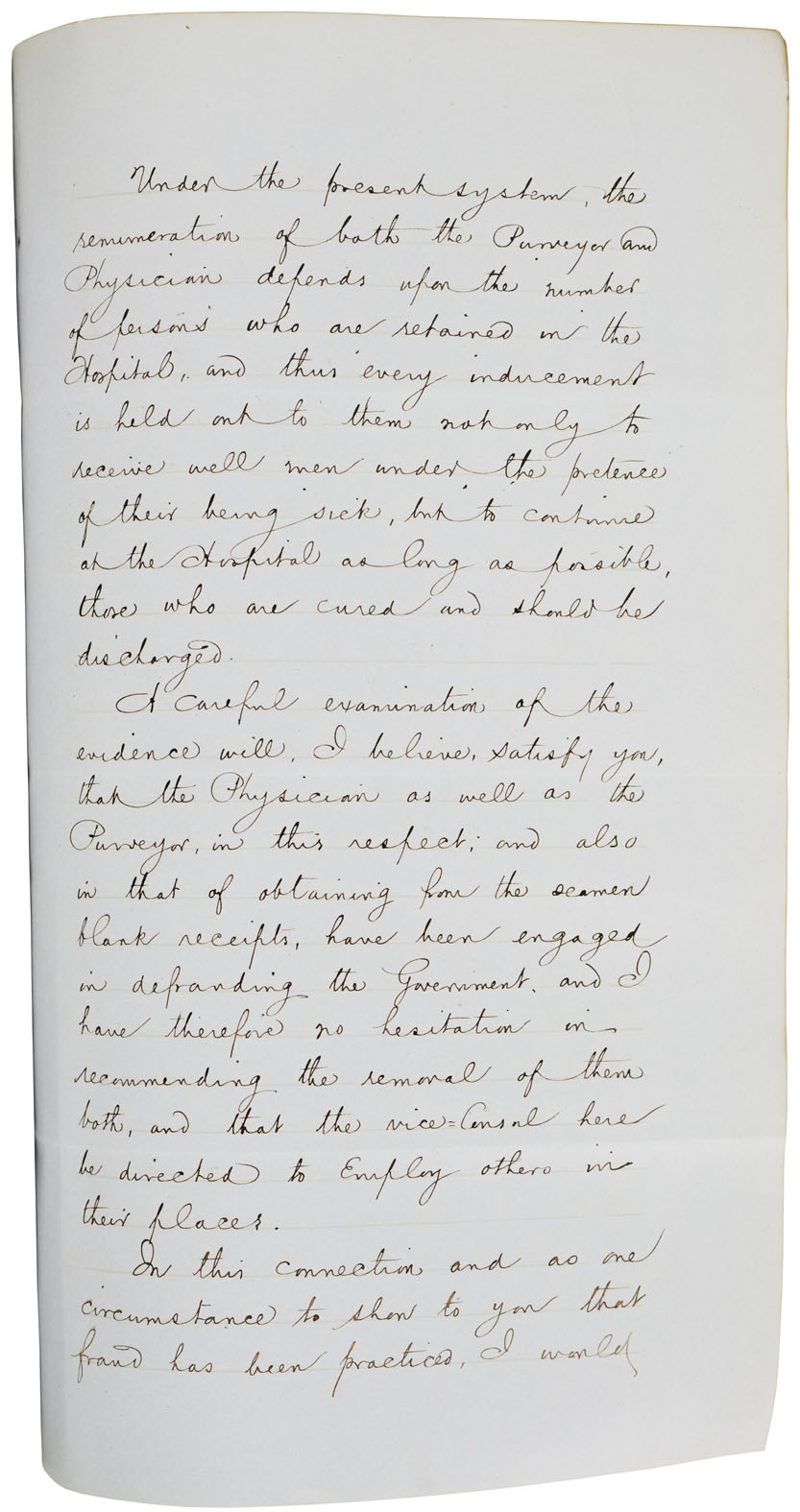

Borden had begun his investigation, seemingly, as soon as Pratt had left the kingdom. In a sworn statement on February 25, 1860, Robert Lett, a 37-year-old shoemaker and sailor, described to Borden the conditions that led to the extremely high hospital costs in Hawaii.

During Pratt's tenure as consul, Lett had spent nine months in the American hospital. Borden recorded Lett's account of the fraudulent practices and sent the deposition to Washington.

While he was there it was a matter-of-fact of very frequent occurrence, that, after the men in the Hospital were cured and well and should have been discharged from the Hospital, the physician and purveyor retained them in the hospital while they went out daily into town to work. They usually went out from the hospital in the morning. [Lett] does not know for whom they worked as he was most of the time lame and unable to walk about the town. These men were well and there was no necessity for their remaining in the hospital.

Lett described in detail the scheme and its participants. Pratt, Dr. Guillou, and the purveyor of the hospital, were all involved.

A Hawaiian law that prohibited healthy seamen from legally remaining in the islands unintentionally aided the participants of the scheme. To have "disabled" seamen on the books, the consul and his staff forced sailors to remain at the hospital indefinitely.

"As by the laws of these islands, no seaman discharged can remain here but a short time and no one can leave the Hospital but by the direction of the hospital as long as the consul pleases and they always consider themselves, when here, as under his jurisdiction and must obey his orders," Lett said.

Patients were forced to sign their names on countless blank receipts. These receipts were filled in for large amounts of cash and sent to Washington for reimbursement.

During the nine months [Lett] was in the hospital, he signed all the receipts to which he placed his name in blank. [By Lett's recollection], these were always signed in double or triple receipt; they were printed forms and were usually signed just as they came from the press, that is without the mark of pen or pencil on them. Lett signed his receipts regularly at each quarter, as the others did, for board, clothing and other articles he had received and also for medicines, etc. but that is was always done with blank receipts and Lawton's steward stood by him and others and, he supposed, witnessed the receipts afterwards by placing his name to them.

To the best of Lett's knowledge, not once was a legitimate receipt even submitted to the U.S. government during his time at the hospital.

To Lett, it seemed most officials at the hospital either participated in the fraudulent scheme or were at least aware of it. Some seamen had seemed to believe the fraud had been perpetrated by only the hospital employees. These seamen had appealed to the consul for help and became dismayed when Pratt ordered the seamen to do as the employees requested.

The scheme continued at the hospital after Lett was discharged. As a shoemaker in Honolulu, his customers were often residents at the hospital, and they told him the fraud had continued until shortly after the participants discovered they were being investigated.

Lett also testified to Borden that Pratt had continued the now-illegal practice of charging fees for all sorts of his services: "It was generally believed among seamen that the captains permitted these illegal exactions to be made from the seamen in return for the consul's favoring the captains in various ways. The accounts of the seamen engaged in the whaling vessels are usually adjusted and settled in the consul's office by his clerks."

The captains of the merchant vessels that docked in Hawaii as well as their officers seem to have tolerated the fraud because the consul almost always acted in their favor. In the mid-1800s, whaling crews received as their payment a set percentage of the ship's entire shipment of whale oil. The more whale oil a crew rendered, the higher were their earnings.

"[Lett] thinks in all cases where there is a dispute between captain and crew as to the number of 'hail' or number of barrels on board, the consul decides the matter," recorded Borden.

Lett was not the only one to expose the scheme. Many other American seamen corroborated his testimony in their own discussions with Borden. Assisting Borden during some of the hearings was one of Pratt's predecessors, Elisha Allen, who had become Hawaii's chief justice.

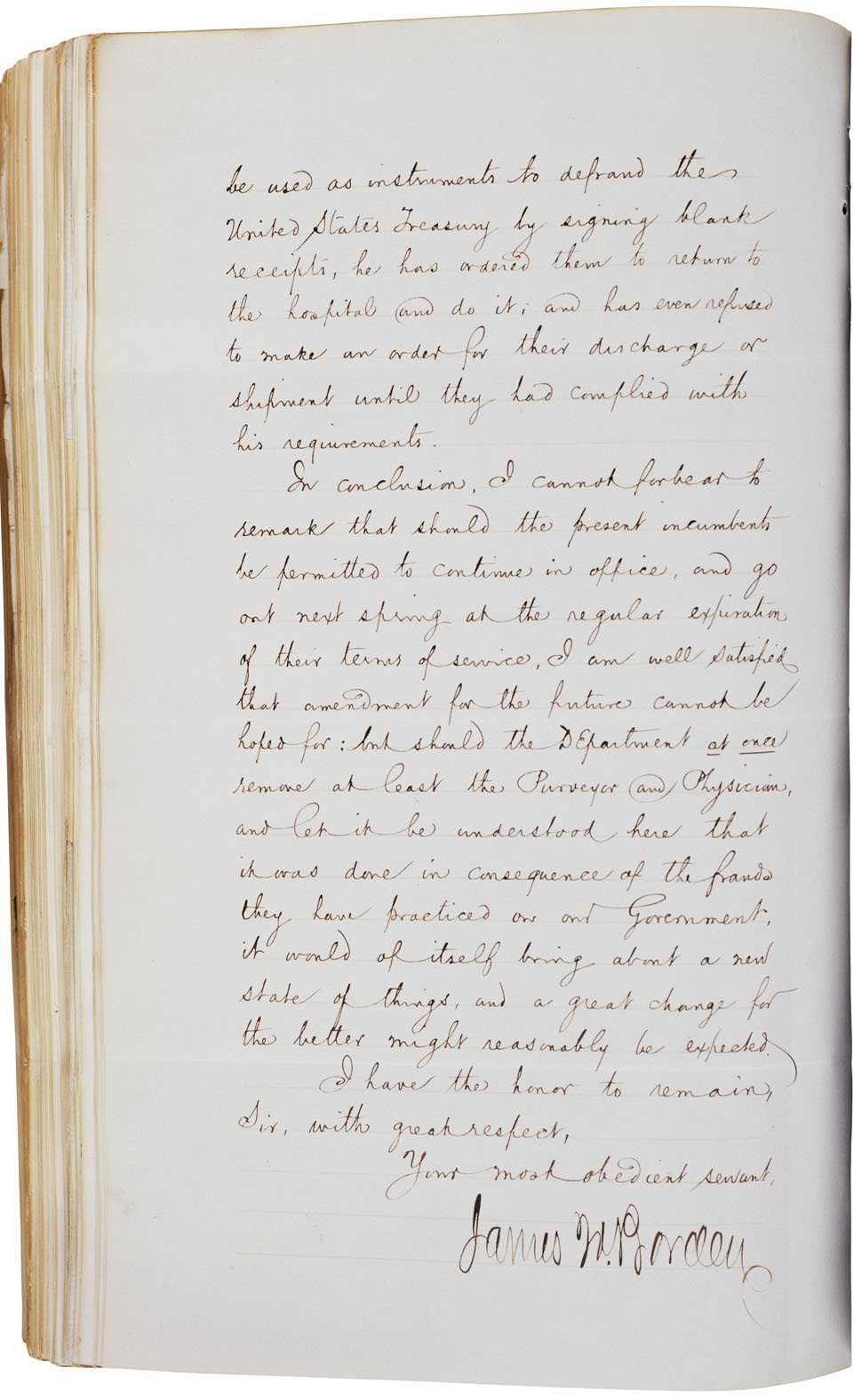

Six months after Pratt had left Honolulu, the USS Levant sailed into Honolulu Harbor with its commanding officer, Comdr. William E. Hunt, serving as the special commissioner to investigate the U.S. consulates and hospitals in Hawaii. The top representative of the State Department in Hawaii, U.S. Commissioner James W. Borden, served as associate commissioner. Acting Consul Thomas T. Dougherty, who had been designated by Pratt as his temporary replacement, was not part of the investigative hearings.

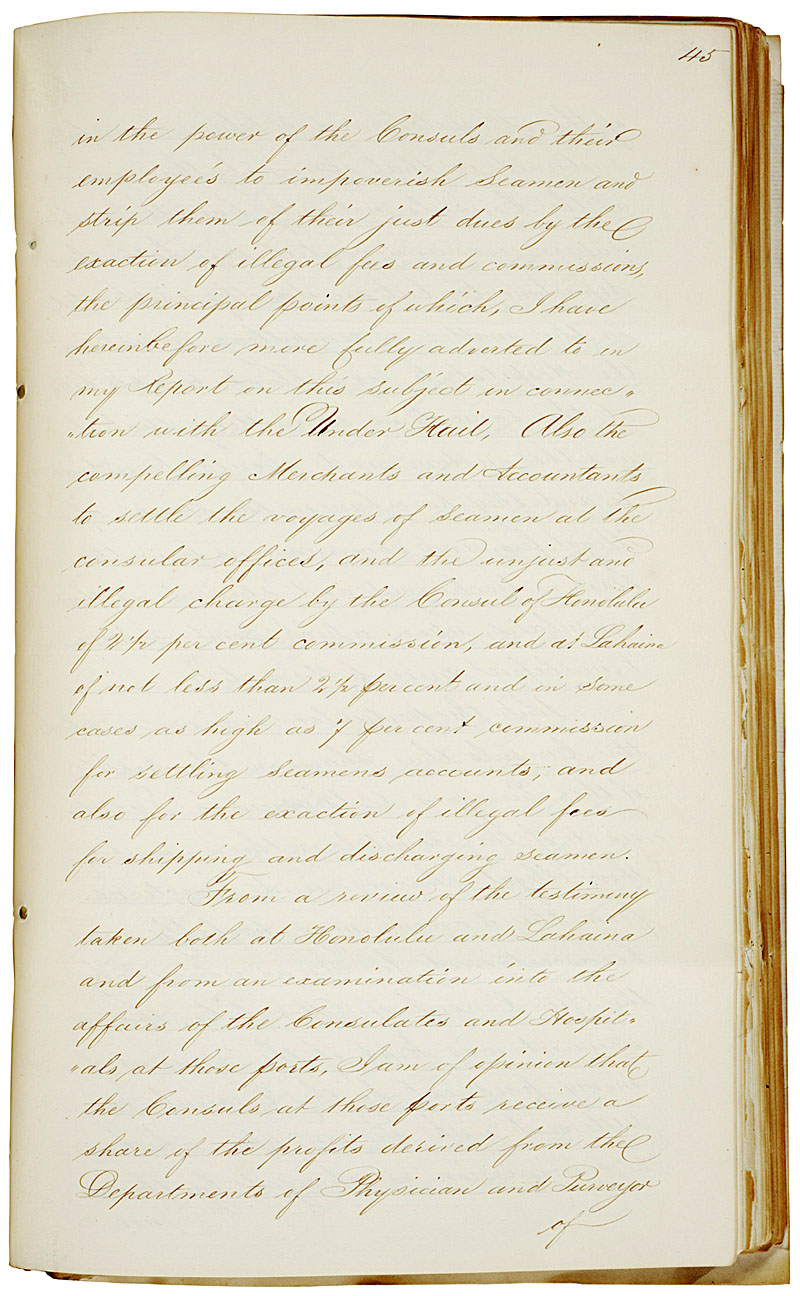

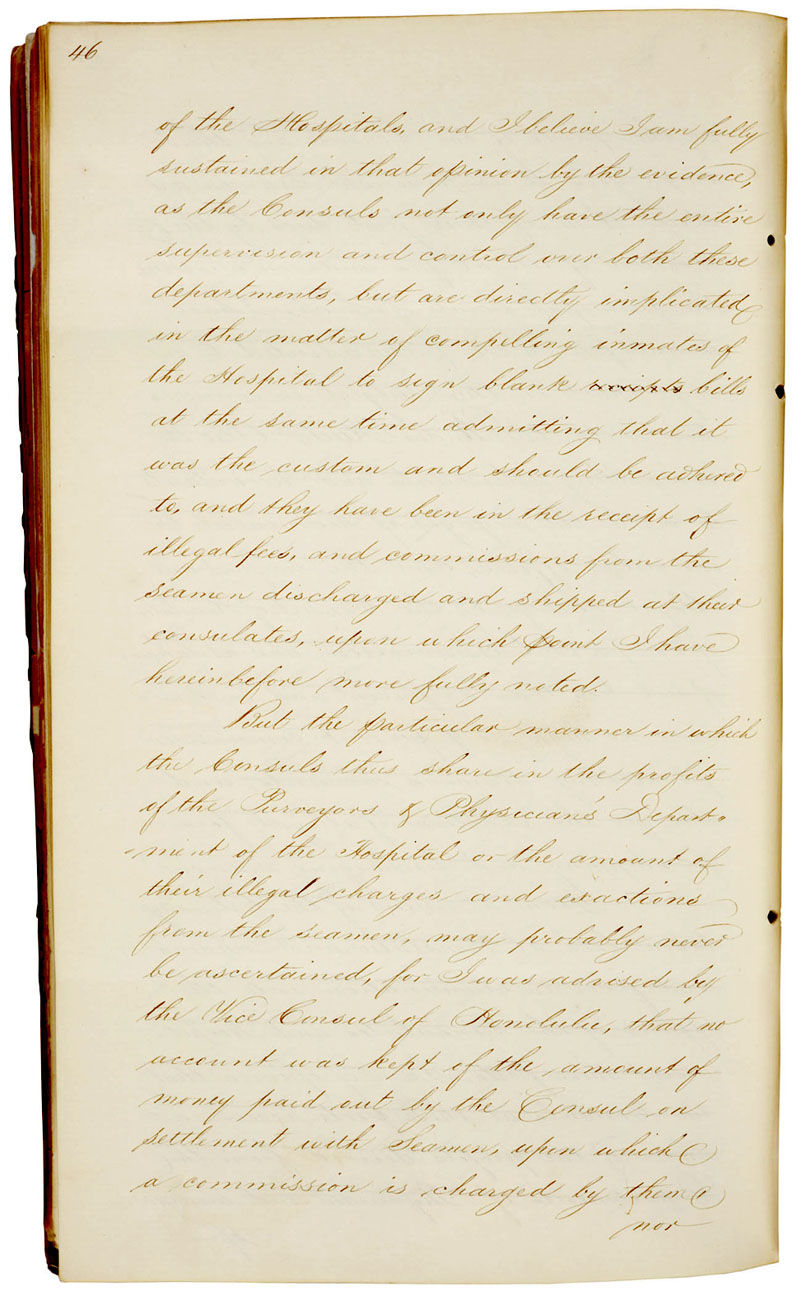

After Hunt and Borden concluded their investigation, Borden sent his version of the report to the State Department. Hunt's official report to the secretary of state never arrived in Washington due to the wreck of the Levant; however, a second version that had been sent to Washington on another ship, survived. Written on September 14, 1860, while Hunt was at the port city of Hilo on the Island of Hawaii, the second version was sent to Secretary of the Navy Isaac Toucey. This copy still exists within the National Archives. Interestingly, a version of the investigation was also leaked to a newspaper reporter who was instructed to only publish the report if the Levant did not survive its return journey to the United States.

This version of the investigation, dated one month after the Levant's disappearance, was first published in a Boston newspaper. The report appeared in the Pacific Commercial Advertiser of February 28, 1861.

"Seamen have been retained in the hospitals long after they had recovered their health and demanded their discharge. And such being the fact in many instances the opinion (and a well-founded one, too) of every man in this community is that such as course is pursued by the consuls for the purpose of profiting from the charge against the government for board and lodging, medical attendance and clothing furnished such inmates, and it is self-evident that the consuls share in such profits fraudulently and corruptly derived," wrote the anonymous informant, who is described as a member of Hunt's board of investigation.

The investigator was blunt in terms of specific charges of fraud that were alleged to have taken place at the Honolulu consulate.

"The amount thus illegally paid by the sailor at the consulate of Honolulu being not much less than $5,000 for commissions on wages, and the sum of $1 for shipping, and the retention of $1 from the two-months' extra wages, swells the illegal and unjust exactions of this consulate to the enormous sum of $9,000 per annum," wrote the investigator.

With the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, the federal government had more important concerns than investigating corruption among the consular corps of the State Department. After the war, Honolulu was not a major worry, but some of the U.S. consuls in China were particularly corrupt. (An interesting side-note for those interested in Civil War history: One of the State Department's best corruption fighters was once a cavalry commander known as "The Grey Ghost of the Confederacy," Col. John Mosby. Mosby became a member of the Republican Party after the war and was rewarded with a position in the federal government.)

After Pratt returned home to Marshall, Michigan, he never stopped having nostalgic feelings for the time he and his wife had spent in Hawaii. At a cost of $20,000, Pratt built a home that bore a strong resemblance to the royal palace of Kamehameha IV and Queen Emma. Their palace was demolished in 1879 because it had been ruined by termite damage. The royal palace that now stands in Honolulu was completed in 1882 by Hawaii's King Kalakaua.

Honolulu House, as Pratt's Michigan home has come to be known, displays a combination of tropical fantasy and Victorian architecture. Its colorful green, red, and ivory painted facade features a wide Hawaiian-style lanai (verandah) and decorative railings.

A brochure published by the Marshall Historical Society provides a colorful description of Honolulu House: "The house is of true tropical architecture—fifteen-foot ceilings, ten-foot doors, long, open galleries with the dining room and kitchen on the ground level. A circular freestanding staircase rises from the lower level to an observation platform more than thirty feet above. The walls in the interior of the house were painted to depict scenes from the islands."

In his 1993 book A History of Marshall, town historian Richard Carver compared the architectural style of Pratt's Honolulu House with that of King Kalakaua's much larger Iolani Palace and recognized some similarities. Up until 2006, he had not seen any images of King Kamehameha IV's Iolani Palace. When Carver was shown images of the original palace by the author, he agreed the first palace could have influenced Pratt's design.

He added that, sadly, Pratt did not get to enjoy the house for long. Pratt, who often wore tropical clothing more suitable for Hawaii than winter in Michigan, died of pneumonia on March 27, 1863, after he had returned home in inclement weather from a trip to the state capital in Lansing. At the time of his death, Pratt had been serving in the state legislature. His wife died in 1861.

Each year, thousands of tourists interested in the architectural history of the 19th century visit Marshall. In a town known for architectural preservation, Pratt's home has a unique honor of preserving not only Michigan history but also a piece of Hawaiian history.

Peter von Buol is an adjunct professor of journalism at Columbia College-Chicago, where he teaches broadcast journalism. Since childhood, he has been interested in the history of Hawaii and the Pacific. As a freelance journalist, he frequently writes about Hawaiian history and Hawaii's unique wildlife. He is also a docent at Chicago's Field Museum of Natural History in its Pacific Halls.

Note on Sources

The official record of Abner Pratt's service and the subsequent investigation with the State Department is found in Record 59, General Records of the Department of State at the National Archives. Three series within that record group are of particular importance: Consular Instructions of the Department of State, 1801–1834 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M78), Despatches from U.S. Ministers to Hawaii, 1843–1900 (National Archives Microfilm Publication T30), and Despatches From U.S. Consuls in Honolulu, Hawaii, 1820–1903 (M144). Borden's investigation of Pratt is found in T30.

Honolulu-based historian Rhoda A. Hackler's doctoral thesis, "Our Men in the Pacific: A Chronicle of United States Consular Officers at Seven Ports in the Pacific Islands and Australasia during the 19th Century" (Ph.D. diss., University of Hawaii, 1978) continues to be the most thorough report on the U.S. consular corps in the 19th-century Pacific. Hackler's great-great-grandfather, Capt. William Cox, was a New England–based whaling captain.

A valuable source of information about the Lahaina-based consul Bunker was historian Dorothy Pyle's article "The Intriguing Seamen's Hospital," The Hawaiian Journal of History 8 (1974): 121–135. At the end of her article, Pyle republished the entire article that had appeared in the Pacific Commercial Advertiser after the sinking of the Levant.

The archive of the Pacific Commercial Advertiser newspaper (now the Honolulu Advertiser) is itself an important historical record.

Australian historian Gavan Daws described Honolulu during Pratt's time in his article "Honolulu in the 19th Century: Notes on the Emergence of Urban Society in Hawaii," Journal of Pacific History 2 (1967): 77–96.

Retired State Department consular officer Charles Stuart Kennedy's book, The American Consul: A History of the United States Consular Service, 1776–1914 (New York: Greenwood Press, 1990) is the definitive history of the American consular service.

The late historian Ralph S. Kuykendall wrote an article and a book that were used as sources by the author. Kuykendall's article "Hawaiian Diplomatic Correspondence" (Honolulu, Historical Commission of the Territory of Hawaii, Vol. 1, no. 3, 1926) was an important navigational tool for the records of the State Department, and his three-volume history of Hawaii, The Hawaiian Kingdom (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1953) continues to be relevant.

Perhaps the leading authority on Hawaiian shipwrecks today, Richard W. Rogers, described his research into the loss of the Levant in his book Shipwrecks of Hawaii: A Maritime History of the Big Island (Haleiwa, Pilialoha Press, 1999).

Briton Cooper Busch's Whaling Will Never Do for Me: The American Whaleman in the Nineteenth Century (Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 1994) is a well-detailed look at the life of 19th-century whalers.

Whale Song, a pictorial history of whaling and Hawaii (Honolulu: Beyond Words, 1986) by MacKinnon Simpson and late Robert B. Goodman, provides a colorful and accurate description of life among whaling vessels in the 1800s.