Voices of Emancipation

Union Pension Files Giving Voice to Former Slaves

Winter 2005, Vol. 37, No. 4

By Donald R. Shaffer and Elizabeth Regosin

© 2005 by Donald R. Shaffer and Elizabeth Regosin

In May 1911, Samuel W. K. Dague, a "special examiner," or field investigator, of the U.S. Pension Bureau, interviewed Dick Lewis Barnett, a black Civil War veteran. Barnett had applied for a pension two years earlier based on his service in the Union army's 77th U.S. Colored Infantry (USCI).

Since 1862, the federal government had paid pensions to Union soldiers and sailors disabled as a result of their Civil War service and to the families of men killed during the war. In 1890, the required connection between disability and wartime service had been dropped; now just about any veteran still living and not in perfect health (or his widow if he was dead) could collect benefits.

Dague was no doubt curious why Barnett had waited so long to apply for a pension. Yet that was not the reason why the special examiner traveled to the veteran's home in Okmulgee, Oklahoma, to question him. Barnett had claimed he served the Union under the name "Lewis Smith." His inability to provide satisfactory evidence to the Pension Bureau proving he was Smith prompted Dague's visit. The subsequent testimony revealed fascinating information about Barnett's experiences as a slave and as a soldier in the USCI.

While the bureaucratic process of proving eligibility was no doubt a great burden to Dick Lewis Barnett and many thousands of other black Civil War pension applicants, it is a windfall to historians seeking to give a voice to those whom history has silenced.

Unlike those with more social and material advantages, who often generate ample written evidence about their lives, people plagued by illiteracy, poverty, and a marginalized social position tend to produce a thinner paper trail-and sometimes none at all. Certainly this situation is true of African Americans of the Civil War generation. Seldom did they appear in records, and even more rarely did they leave personal accounts in their own words. Indeed, without the Great Depression, which prompted the creation of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), historians likely would not have the famous narratives of ex-slaves commissioned by the WPA's Federal Writers' Project.

The WPA slave narratives represent a deliberate effort to record for posterity the memories of ex-slaves. Yet the recollections of former slaves have been saved inadvertently as well. First-person accounts of many former slaves, as well as other documents speaking to their lives, appear in the case files of the U.S. Pension Bureau. This agency, a part of the Department of the Interior, administered an enormous pension system for Union veterans of the Civil War, which by the 1890s was swallowing up over 40 percent of the federal budget. In the process of proving their eligibility for pensions, veterans and their survivors invariably had to provide all manner of information about themselves. African Americans, who had served in the Union army and navy, and their immediate families, were able to apply for these pensions on an equal basis with whites, and the data they provided the federal government is now in the holdings of the National Archives.

Civil War pension files have the potential to rival the more famous WPA narratives of ex-slaves in offering evidence on the experiences of 19th-century African Americans from a black point of view. In fact, based on when the information was collected—mainly between the 1880s and 1910s—they are arguably superior. Civil War pension files are much more contemporaneous to the experiences of slavery, the Civil War, and their aftermath than the WPA narratives, which were not gathered until the mid-to-late 1930s. Many pension files include in-depth interviews of former slaves by special examiners for the purpose of clarifying information on such issues as military service, identity, health and disability, marital and family relationships, employment, economic circumstances, and previous ownership. The depositions are often quite effective in giving a voice to former slaves, allowing them the opportunity to talk about their lives and provide important clues about how they saw the world.

A larger work-in-progress, entitled Voices of Emancipation, a primary source reader under contract with NYU Press, will showcase the value of pension files in documenting the experience of former slaves, especially as they themselves described it, before, during, and after the Civil War. The cases discussed here will communicate a sense of the embarrassment of riches regarding former slaves in the Civil War pension files available at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

To prove he was same person as "Lewis Smith," Dick Lewis Barnett had to tell Samuel W.K. Dague much of his life story. Although special examiners usually came into depositions with an agenda of issues to clarify, most examiners did not stick strictly to the planned topics. The depositions of black applicants are therefore often rich with biographical details. This was certainly the case for Dague's interview of Barnett, who begins his life story by saying:

I was born in Montgomery Co. Ala. The child of Phillis Houston, slave of Sol Smith. When I was born my mother took the name of Phillis Smith and I took the name of Smith too. I was called mostly Lewis Smith till after the war, although I was named Dick Lewis Smith—Dick was the brother of John Barnett whom I learned was my father after I got back from the war, when my mother told me that John Barnett was my father.

Dick Lewis Barnett in this passage tells much about the experience of slaves before the Civil War. That Barnett was of mixed race parentage is not surprising, nor is it a stunning revelation that he did not know the name of his white father until after the war. What is interesting is the fluidity of his identity as reflected in the paragraph. One finds not two, but three name variations. He applied for a pension as Dick Lewis Barnett, the name he adopted in the postwar period. Yet while he was a slave he also was sometimes known as Lewis Smith and Dick Lewis Smith.

Other Civil War pension files make clear that this ambiguity of identity was quite common among former slaves. In fact, it was an important reason why African American veterans came under the intense level of scrutiny that characterized special examination. Washington bureaucrats were suspicious of men with aliases because of the association of aliases with criminality. For entirely innocent reasons, it was not at all uncommon for a former black soldier to have used at least two, possibly three or more, identities during his life. Many African American veterans had served in the army under the last name of their owners and then after the war took another surname, often one associated with their families.

Dick Lewis Barnett, it is worth noting, took the name of his father after war, even though John Barnett was white and apparently never acknowledged him. "I was wearing the name of Lewis Smith," Barnett stated later in his deposition, "but I found that the negroes after freedom were taking the names of their father like the white folks. So I asked my mother and she told me my father was John Barnett, a white man, and I took up the name of Barnett." Dick Lewis Barnett's comment is important evidence not only of former slaves adopting new identities after the Civil War but also of the importance of family connections and patriarchy in which names they chose. It speaks volumes of what freedom meant to Barnett that he would adopt the name of a man with whom he apparently had no close relationship. To Barnett (and other black men) being a man clearly meant being known by his father's last name, even if he had not known until after the Civil War that John Barnett was his father, because a free man was known by his father's last name.

The Pension Bureau's main concern was making, or disproving, the connection between Dick Lewis Barnett and a black Union soldier named Lewis Smith. Not surprisingly then, the bulk of Barnett's deposition deals with his military service, and much of that essentially boiled down to what the veteran could remember about the units he served in and comparing them to known facts about those organizations. Still, in the process of quizzing Barnett, interesting details emerge concerning his service, some particular to him and others shedding light on black military service in the Civil War. He remembered:

I was raised on Sol Smith's plantation near Montgomery Ala and I stayed there till December 1862, when I went to Cedar Key Fla 60 miles from Key West Fla with Jacob Smith, my master's son and from there I went to New Orleans La Christmas 1863, and the next February 1864 or March 1864 I enlisted in the U.S. service in Co. B 77 Col. Inf. But was not sworn in until April 1864.

There is much that can be read between the lines here. The first mystery solved is how an Alabama-born slave came to be in the Federal army. Relatively few black men from Alabama served in the Union army because the state largely remained free of Federal occupation until late in the Civil War. The deposition makes fairly clear that Barnett followed his young master into the Confederate army as a body servant and within a year had come within Federal-controlled territory, either fleeing to Union lines or being taken prisoner in the course of military operations. This event would likely have taken place in Florida, because New Orleans, where he joined the army, was under Union control by the end of 1862. Joining in New Orleans also meant that, unlike most soldiers in the Civil War, white or black, he served with men he did not know. Barnett acknowledged as much when he stated in his deposition, "I was a stranger to my comrades when I enlisted; after service I saw none of them until last February when I called Abbott and Grant [two former comrades in Louisiana] to get their affidavits for use in my pension claim."

After joining the 77th USCI, Barnett stated that he "served as a 'musicianer' and my duty was to beat the drum." Joining a unit recruited in New Orleans required something of a cultural adjustment for Barnett, as most of his new comrades "were Creoles—a great many were unable to talk English plainly." He spent his entire service in Louisiana, and like many black soldiers in the Civil War saw no combat, although his unit (later reorganized into 10th U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery) was sent into New Orleans in July 1866 to help restore order after the famous riots in the city that year.

Indeed, what makes Barnett's description of his service so interesting is its very ordinary quality. Except for his unlikely enlistment and being among strangers, his service could have been that of just about any black soldier in the Civil War. What is even more remarkable is that there are countless thousands of other first-person accounts of former black soldiers discussing their Civil War service in the National Archives in Washington, D.C., waiting for perceptive, patient, and diligent scholars to tease out the full significance from them.

After leaving the army in early 1867, Barnett returned to his home near Montgomery, Alabama. He married and worked on various plantations until around 1904 or 1905, when he moved to Okmulgee, Oklahoma, for health reasons. Barnett's pension claim was approved, and he collected money for six years until his death. As his widow, Eliza, reported in an affidavit in her pension application, her husband "was feebel [sic] minded in his last days and wandered away from home on Aug. 6, 1918 and fell into the river and was drowned and was found early in the day of Aug. 7, 1918." As Eliza's affidavit demonstrates, the first-person revelations from pension files are often augmented with details from other documents.

Barnett's case shows how Civil War pension files offer insight into antebellum slavery from those who had lived as slaves. An even more instructive case is that of Charles Washington, who served in the 47th USCI. Aged 89 in 1905, when he testified to a special examiner, Washington had been a slave for nearly half a century when freedom came. No former slave in the WPA narratives was as old at the time of emancipation.

Washington's special examination with A. F. Burnely offers an invaluable firsthand perspective of the internal slave trade that shifted hundreds of thousands of African Americans west in the decades preceding the war to feed the growth of the southern cotton kingdom.

Washington testified that he had been sold a number of times even before he reached adulthood. He explained:

I was born in the state of Florida, and lived there until I was quite a lad of a boy and then I was sold to a man by the name of Thompson, who sold me to a man by the name of Randolph, and was then put into a traders yard at New Orleans, La., and there a man by the name of Dr. Vincent who lived on Joe's Bayou . . . and he owned me for a long time until I was a grown man and had a wife and three children, and then Dr. Vincent . . . sold me to Mr. James Berry, who lived on the Mississippi River.

Washington discusses his experience with the internal slave trade with surprising detachment, perhaps the result of his age and the passage of time. His testimony is unclear as to whether these sales separated him from his family. He mentions that his mother told him his age when he was 12 years old (and also mentions that he became Dr. Vincent's slave at age 11) but says nothing of his father, siblings, or other kin. However, the fact that Washington was sold numerous times, including being sold through "a traders yard" in New Orleans, diminishes the likelihood of his having remained with many other members of his family. Washington concluded that he remained on Dr. Vincent's plantation some 30 or 40 years until "Mr. Berry bought Dr. [Vincent's] plantation and all of his slaves."

Sadly, Washington's story is not unusual. Other special examinations better reveal the emotional toll inflicted by a trade that routinely separated wives from their husbands and parents from their children. Augustus Fletcher, also sold down to Louisiana, poignantly articulated the inhumanity of the domestic slave trade when he stated, "[One soldier] came from Kentucky and was sold down in this country, just as I was and like they sold mules in those days."

Washington noted that he was the only slave to leave his master's plantation to enlist in the Union army during May 1863. More significantly, his experience is a valuable reminder that the separation of slave families occurred not just during slavery but during the tumultuous years of the Civil War as well. He explained that "after I left home to go into the army, Mr. Berry carried all of his slaves who had remained at home, to the state of Texas, and have never heard of any of them. I was a married man, and had three children and he carried them to Texas, and I have never heard of them since." The removal of slaves to Confederate states more remote from the war, like Texas, was not unusual. Planters in the Mississippi Valley forcibly moved as many as 150,000 slaves into Georgia and Alabama as well as Texas to prevent their liberation by Union forces.

While Washington himself did not reveal whether he had searched for his family after the war, Emeline Anderson, a witness in his case, reported that after the war, "Charley was going to get his wife from Texas and he heard she was dead." Washington might well have searched for his children after the war, as had many former slaves who had been separated from family members during slavery or during the war. But it is also likely that he did not-both poverty and illiteracy making it incredibly difficult to do so. After the war, Washington returned to the area in Louisiana where he had spent most of his life. He married Cherry Green in 1870, and some 35 years later the two were still together.

Yet Washington's deposition is not merely firsthand evidence of the inhumanity of the antebellum slave trade in the United States and how the tumult of the Civil War also could separate slave families. The testimony of Washington and veterans like him, and of other witnesses in pension file applications, provide fascinating details on the way in which the slaves viewed their world, especially their perception of time. Like many of his contemporaries, Washington could not give pension officials relevant dates that might have helped prove his case. He explained that he knew his age only because he had kept track of it since the year his mother told him he was 12. To questions of how old he was when he enlisted and when he married Washington responded, "Do not know how long I had been married before I went into the service but had been married long enough to be the father of three children." Emeline Anderson had also been Berry's slave. She testified that "[Washington] had been married a long time before the war, and had two or three children before he went into the army. I would guess that the oldest one was nine or ten years old. He had two boys and think he had one girl."

Washington's response is very typical. Like other pre-industrial people, former slaves did not reckon their world by a calendar or the movement of a clock. They measured the passage of time by the agricultural cycle, the progression of the seasons, and the movement of the sun across the sky. They tended to remember major events, such births, marriages, or the like in relation to other major events. While special examiners expressed frustration about the imprecise manner in which many former slaves understood time, the Pension Bureau was forced to work within the applicants' system. Instead of forcing ex-slaves to understand calendar time, the bureau had to find ways to translate pre-industrial descriptions of time into approximate calendar dates. For example, an 1882 manual for special examiners stated, "In claims by colored persons, it will generally be necessary to call attention to the witnesses to some important event, holiday, &c., to enable them to testify with any approach to accuracy in regard to dates."

The Civil War pension files can be instructive about the former slaves' economic circumstances after the war. While this issue was not a regular concern in pension cases, it comes up often enough to provide tantalizing glimpses of the progress that some freedpeople made in improving their lot after the war. One economic success story was Kitt Mitchell, a black veteran from South Carolina who had served in the 128th USCI. He was interviewed in 1903, in connection with his wife Jane's application for a pension as a dependent mother of their son James, who had died of dysentery in the U.S. army in the Philippines in 1901. Mitchell was already a federal pensioner based on his Civil War service, then receiving the maximum rate of $12 a month under the 1890 law. In the case under investigation, Jane was seeking her own pension on the basis of their dead son's service in the Philippine War (1899–1902), which the army fought to establish American control over the islands after they came into U.S. possession as a result of the Spanish-American War (1898). Because Jane had to prove financial dependence on her dead son for her claim to succeed, the issue of the couple's finances became relevant.

Far from finding a poor lonely black woman who had relied on her son for support, the Pension Bureau discovered a prosperous African American farmer and his family. Perhaps not realizing the significance of his testimony, which would lead to the rejection of his wife's application, Kitt Mitchell testified quite freely of his success. "I own 50 acres of land—all paid for—worth, with the house, about $250.00," he bragged. "I plant 15 acres and if I had the help I could plant 22 acres that much is cleared up." Indeed, rather than being dependent on their children, Mitchell's testimony clearly showed quite the opposite—a daughter and her husband benefited from the parents' affluence. The veteran stated:

My wife & daughters & I work the place & we make one to two bales of cotton—for which I get from $30 to 50—I make from 50 to 100 bus of corn & from 30 to 60 bus of potatoes—and we have a garden—We have two horses—My son-in-law lives with me & works another place—he has no horse—so I arranged with him to do my ploughing for the use of the horses on his land and I feed the horses—& he does the work as promised.

Clearly, his daughter and son-in-law were an integral part of running his small farm, and both generations benefited from the arrangement. The aging veteran received help growing his cotton, corn, and potatoes, and the children got a place to live and the use of his horse. In the context of the Jim Crow South, this African American family did nicely indeed. As Mitchell himself testified, "We do very well when we have a good season, and what we make together with my pension, keeps us going very well."

Civil War pension files also illustrate that many former slaves did not do so well. Certainly, this is no great surprise, yet such cases bear poignant witness to the poverty that many former slaves endured and give a human face to their plight. While a relatively wealthy ex-slave like Kitt Mitchell boasted of his success, veterans and other impoverished ex-slaves were understandably reluctant to discuss their situations. It fell to others, the special examiners in particular, to tell their stories.

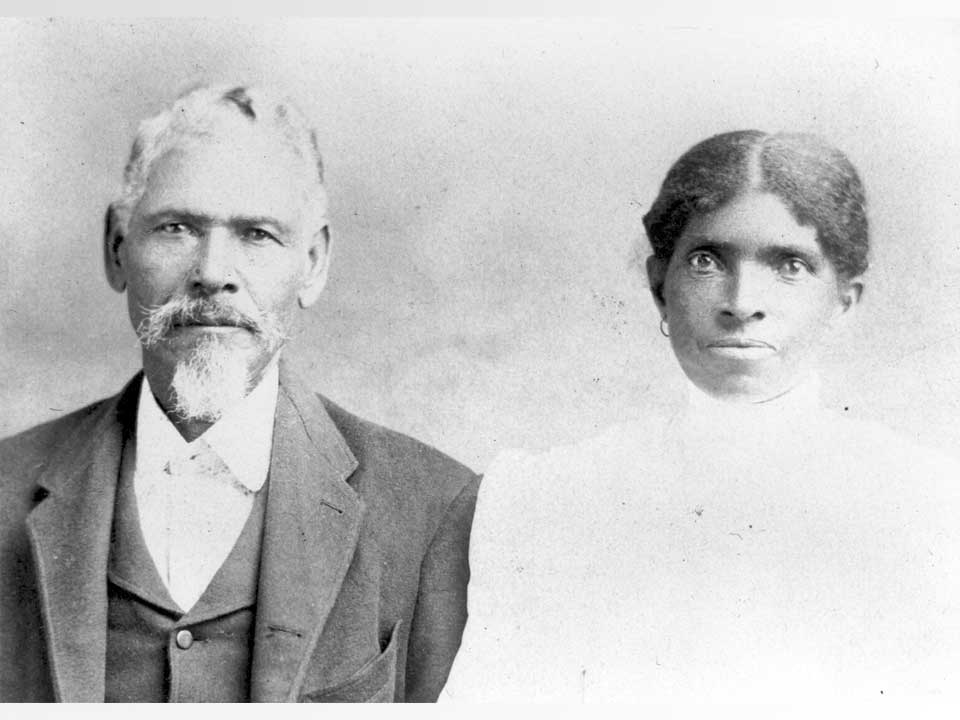

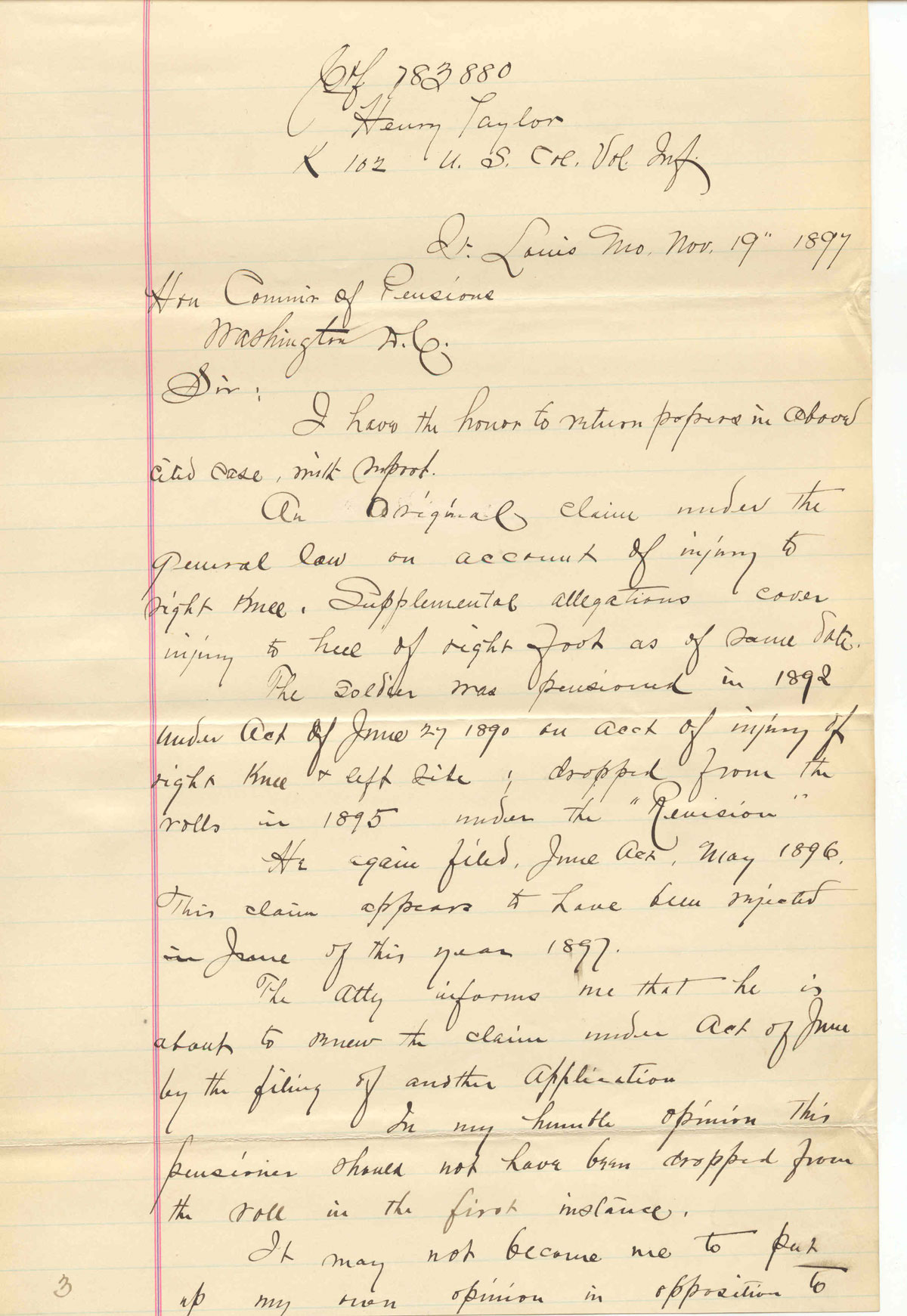

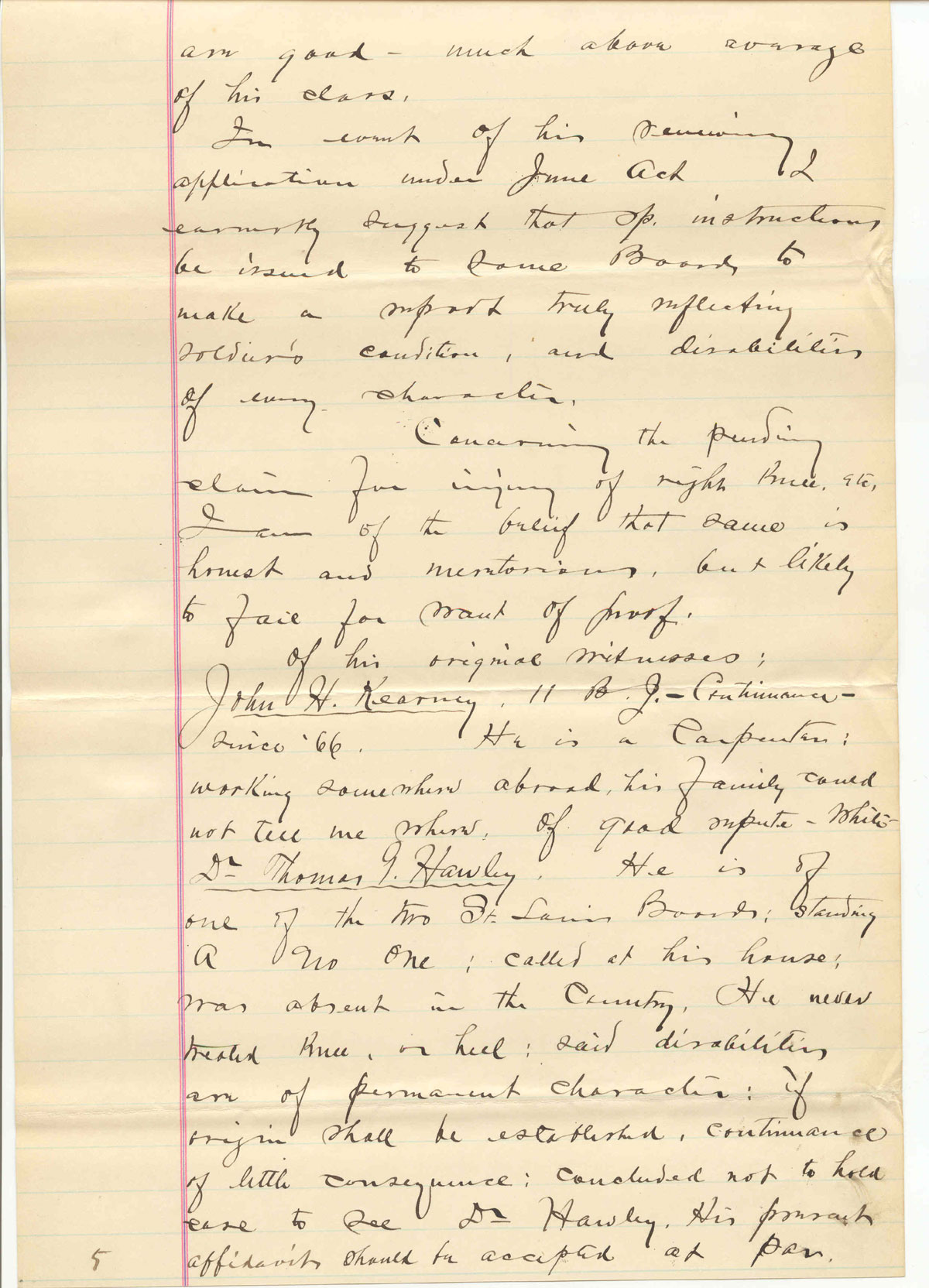

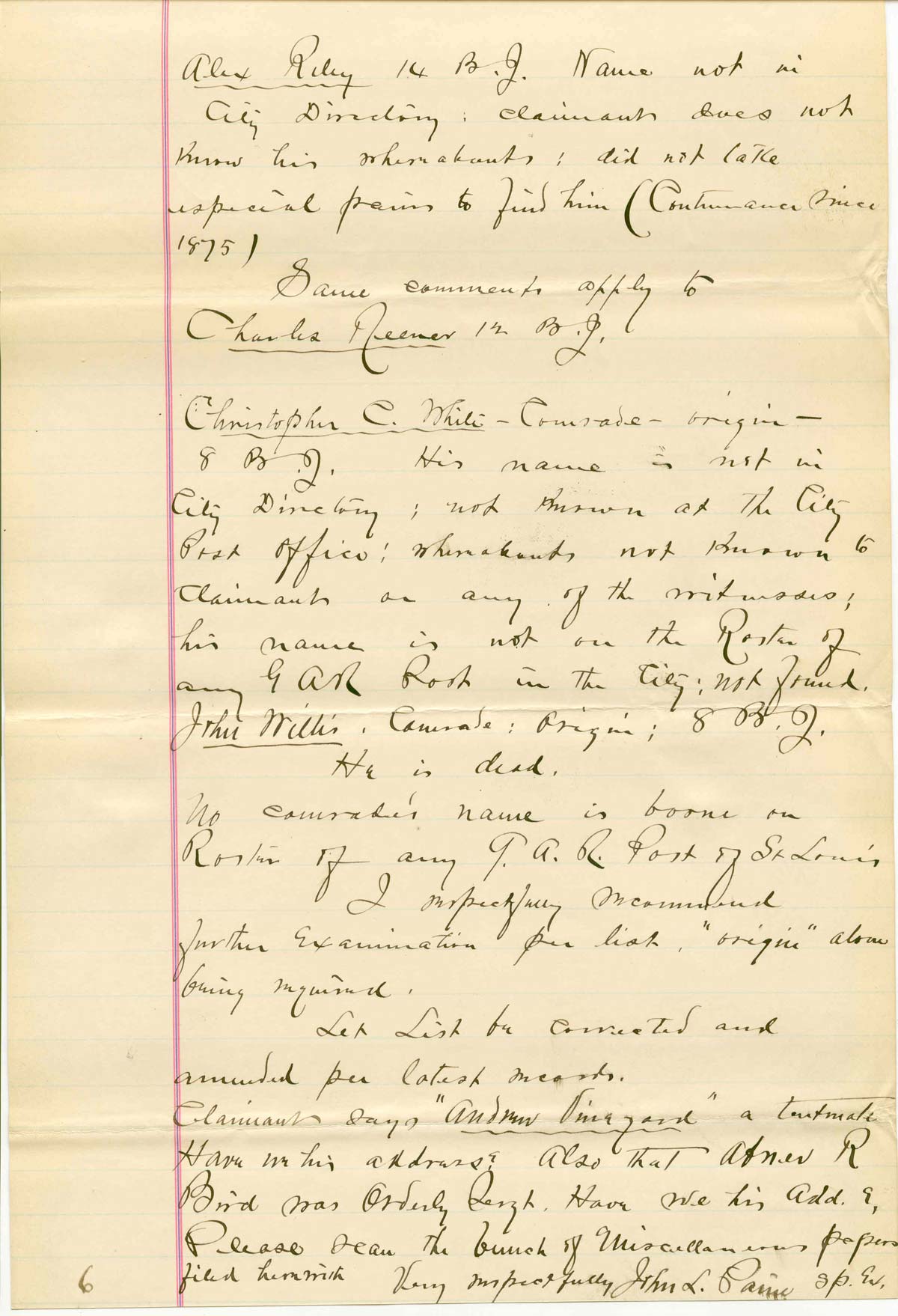

One particularly moving case concerns Henry Taylor, a veteran of the 102nd USCI living in St. Louis. Taylor had applied for a pension under the 1890 law and was approved in 1892 "on acct of injury of right knee & left side." He might never have encountered a special examiner had the ex-soldier not been a victim of the so-called "Revision" that took place in 1895. Many Civil War pensioners had their pensions slashed or—like Taylor—lost them entirely during the second administration of Grover Cleveland (1893-1897). Cleveland, a Democrat, believed that previous Republican administrations had been far too generous in pensioning ex-soldiers and their survivors and forced the Pension Bureau to reevaluate all pensions using tougher disability criteria.

Taylor applied for the reinstatement of his pension in May 1896, but his claim was rejected. He was preparing a new application for reinstatement when an outstanding claim under the original 1862 pension law, in which the veteran asserted his disabilities were service-related (which would have gotten him a more generous pension than under the 1890 act and a large lump sum for unpaid "arrears" going back to the Civil War), prompted the special examination.

Henry Taylor found a friend and ally in Special Examiner John L. Paine. Paine stated quite plainly in his report on his interview with Taylor, "In my humble opinion the pensioner should not have been dropped from the [pension] roll in the first instance."

Letter of John L. Paine, Special Examiner, St. Louis, Mo., to the Commissioner of Pensions, Washington, D.C., Nov. 19, 1897

Source: Civil War Pension File of Henry Taylor, Co. K, 102nd U.S. Colored Infantry, Record Group 15, Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Read the transcript

The examiner then went on to castigate the local medical board in St. Louis (one of many nationwide that evaluated all veterans' disability claims for the Pension Bureau) for overlooking the ex-soldier's obvious infirmities. Paine stated, based on his first-person observation of Taylor, that "His mouth is as crooked as letter Q or I—facial paralysis, and I do not believe that the cause of same has limited its symptoms & effects to face, or mouth, alone. The man is a cripple. That is certain. He suffers neuralgia pains from broken ribs—am certain of that."

Yet it was Paine's comments on Taylor's poverty that are the most heartrending, comments that make it clear the special examiner was extraordinarily acquainted with Paine's situation. "He has been a familiar figure to me for six months," wrote Paine. "[I] have seen him time and again hobbling with his cane and rag hook, and bag, doing the alleys and gutters for rags. He does not earn two dollars a week."

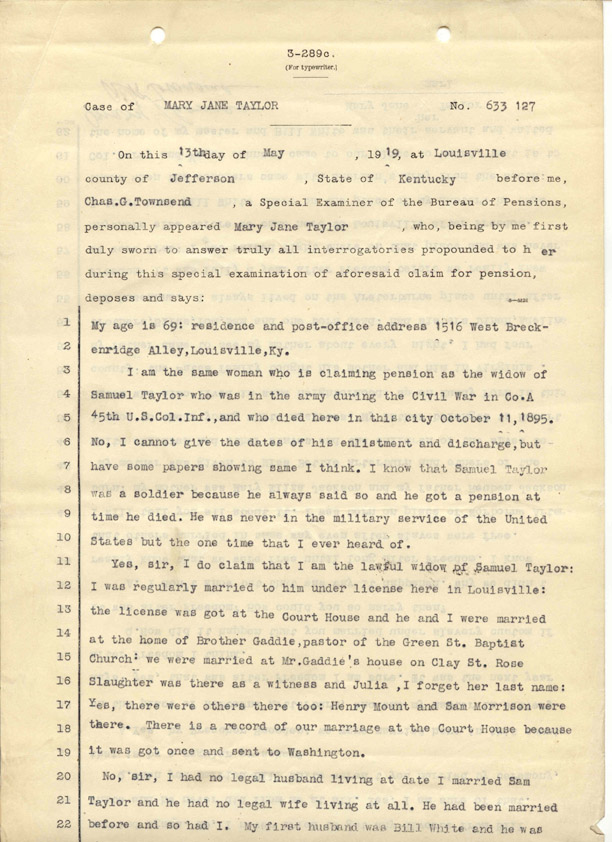

As Henry Taylor's case shows yet again, an important virtue of Civil War pension files is the presence of other documents to further explain information provided by witnesses in the special examination depositions. The case of Mary Jane Taylor, widow of Samuel Taylor, a black veteran from Kentucky, offers another good example of the dynamism of the evidence in the pension files. Because veterans' survivors, widows especially, could collect pensions in their own right, many pension files reveal as much about the families of former black soldiers as they do about the veterans themselves.

Perhaps ironically, the pension claims of African American widows are particularly enlightening because of the racism of the white bureaucrats who administered the pension program. Deeply suspicious of the morality of black women, and charged by federal law to deny a pension to any widow who did not remain chaste after the death of her husband, pension officials subjected many black women like Mary Jane Taylor to intensive investigations of their sexual histories.

While such probes must have been humiliating to Taylor and the other women, they also bear witness to the ways in which women like Taylor pushed back against the system, suggesting that the rights of citizenship accorded to them in the pension process emboldened them as well. Widows' pension files offer historians an abundance of information about family and marriage in the black community in the wake of emancipation, providing a more nuanced picture of the revolution in the intimate lives of African Americans of the Civil War generation.

Before the Civil War, southern laws ignored and thus failed to protect slave marriages. Although couples did marry, slaveholders exercised veto power over such unions. They also could end marriages by selling off one partner or otherwise separating a couple through physical distance. Emancipation brought legal sanction and protection to slave marriages. Once freedom became a fact in the South, even white Southerners acknowledged that black people should have the right to legal marriage, if for no other reason than to hold them responsible if they did not fulfill the duties that went with it. In any case, in the years following the war's end, countless couples formalized marital bonds forged in slavery. They were encouraged to do so by Union occupation authorities and by leaders among their own people, who saw legal marriage as a way to bring respectability to the black community and as a first step in obtaining additional citizenship rights, such as suffrage.

While pension files do not contradict this view, they show the transformation to have been more gradual than previously known. For some decades after emancipation, two systems of marriage co-existed among former slaves, one rooted in freedom and the other hearkening back to bondage. For one thing, marriage did not encompass all romantic pairings of slaves. More informal unions existed and were accepted in the slave community. Further, once freedom came, not all slave couples rushed to formalize their unions; many were happy to live as they always had and did not feel compelled to abide by the law. Still others in the postwar period continued to initiate informal relationships reminiscent of slavery. Mary Jane Taylor's case is an excellent example of how slave marriage customs survived after the war and how they were gradually supplanted by legal marriage in the black community. In addition, her pension file shows that both black and white people in the postwar South were aware that this transition was taking place around them.

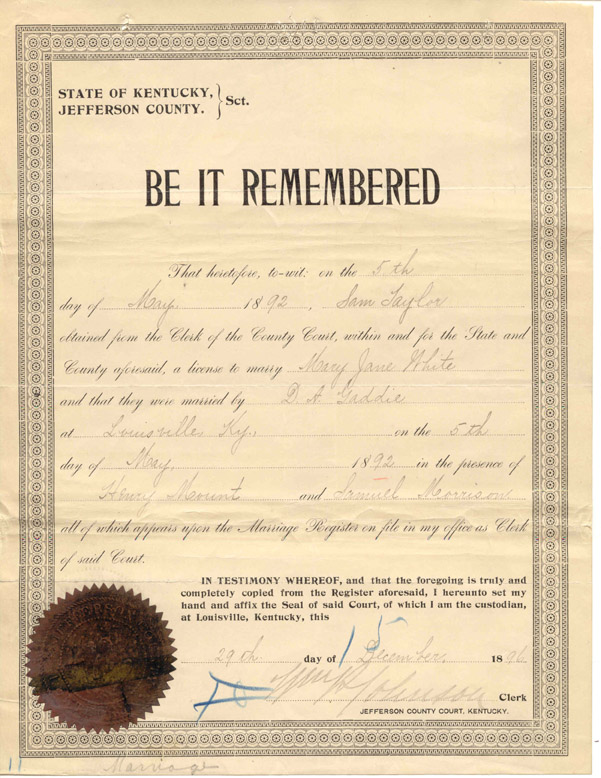

Mary Jane White had married Samuel Taylor on May 5, 1892. According to Mary Jane's special examination deposition, dated May 13, 1919, it was her second and her husband's third marriage. Samuel Taylor died in 1895, and under the terms of the 1890 pension law, Mary Jane was not entitled to claim a pension as Samuel's widow because she had married him after the passage of the 1890 law. She tried to get around this limitation by filing a widow's claim under the original 1862 Civil War pension statute, which did not have such a limitation but did demand that the veteran's death be in some way service related. This claim was denied because she could not prove Samuel's death from tuberculosis was connected in any way to his Civil War service. At best, she was able to collect the accrued pension owed to Samuel by the federal government at the time of his death.

There matters rested for some years until new legislation passed by Congress in September 1916 made marriages entered into during or before 1905 eligible for widows' claims. When Mary Jane applied under this new law, pension officials forced her to submit to special examination because of "contradictory statements relative to her prior marital history." Only a widow who could prove a legal marriage to her husband was eligible for a pension, and in the opinion of the U.S. Pension Bureau, the circumstances of how her marriage to her first husband, Bill White, ended were unclear.

Just as it clarified her marital history, Mary Jane Taylor's deposition of May 13, 1919, also revealed much about the process by which informal marriage customs rooted in slavery were gradually replaced by legal marriage in the postwar South. Taylor's deposition is valuable because she was involved in both the informal and legal system, and she had much to say about their difference.

She married her first husband, Bill White, an escaped Alabama slave, toward the end of the Civil War. He was the servant of Union officers who boarded with her owner, Bettie Arterburn in Kentucky. After the officers left, White stayed on and hired out to Arterburn. Mary Jane was adamant in her deposition, however, that she had not legally married White. The marriage took place sometime in 1865, when slavery was still legal in Kentucky. The state was exempt from the Emancipation Proclamation, and slavery was not abolished there until the 13th amendment went into effect at the end of that year. Taylor evidently sought and received Arterburn's permission for the union as was the practice under slavery.

After freedom finally came, the couple moved with her father first to Indianapolis, Indiana, and then to Louisville, Kentucky. Their marriage was beset with conflict aggravated by Bill's alcoholism. Taylor stated, "We separated three different times and then he would come back and want me to live with him." Eventually the couple parted for good.

It was here in the story that the contentious aspects of Mary Jane Taylor's history manifested themselves. In order to be a legal widow, Taylor would have had to have legally dissolved her marriage to Bill White. Her application for a pension had stated she had been divorced from White, but the Pension Bureau's intensive search of local records in Louisville had produced no divorce judgment. In her deposition, Taylor also was adamant that there had never been a divorce. She stated of White, "he was not my legal husband at all," adding, "he and I were married under the Old Constitution by slave custom and we didn't have to get any divorce at all they said."

Taylor's contention was absolutely correct under Kentucky law. In that state, couples who wished to legalize their slave marriage were required by an 1866 law to make a written declaration with local authorities to legalize an existing slave marriage. Because Taylor had never ratified her marriage with White, it was never legal, and no divorce was necessary—which also meant she was perfectly free to marry Samuel Taylor. Because Mary Jane and Samuel had taken out a marriage license, her marriage to the veteran was legitimate in the eyes of the federal government, and she was entitled to a pension.

Yet the significance of Mary Jane Taylor's case goes much beyond the eventual success of her pension application. It highlights the survival of slave marriage practices well into the postwar period, what Taylor refers to quite aptly as "the Old Constitution." Couples continued to marry informally, not seeking a marriage license, in some cases dispensing with a ceremony altogether, as had been the case in the days of slavery. They also did not seek legal divorces, considering the marriage at an end when cohabitation ceased.

What is also significant here is that Mary Jane Taylor doesn't seem at all victimized by her experience under special examination. Rather, her insistence that pension officials interpret her relationships just as she laid them out suggests that she exercised some element of control over the process. The fact that she had been with Bill White for more than 10 years (however "on again, off again"), that they moved together from Kentucky to Indiana and back, and that they had several children together might well have been considered as evidence of a legitimate marriage, regardless of its origin. In fact, many former slave widows successfully made similar arguments in their claims when they applied for pensions with no material evidence of a marriage. But Mary Jane made sure to emphasize that her marriage to Bill White was not legitimate: "He was not my legal husband at all. . . . We weren't regularly married at all." She cemented her case, whether purposefully or not, by appealing to pension officials' sense of morality, pointing to the fact that Bill White abused alcohol.

Beyond Mary Jane's personal story, her pension file reveals information about her family's experience after slavery. In her explanation of her marriages, she gave her family history, explaining that her parents lived on different plantations but that her father visited Mary Jane, her mother, and her six brothers and sisters every night. Her father ran away to Indianapolis but returned for the family after the war's end and took them all back to Indianapolis with him. When they returned to Kentucky, Mary Jane's father had enough money to buy some land and to "put up a little cabin . . . [which] was added to from time to time: this was the home of my father until he died and of my mother until she died." Mary Jane, still working as a cook at age 69, was living in that same house in 1919. Interestingly, a number of the witnesses in her case were family and other people who had known her "since she was a girl in slavery," suggesting that a number of people from her slave community remained nearby. In addition to the facts of her case, then, Mary Jane's pension file gives readers a sense of the broader context of this former slave's life.

As the cases profiled here demonstrate, Civil War pension files in general, and the depositions to special examiners in particular, provide a valuable window onto the lives of former slaves comparable at the very least to the WPA slave narratives and in some ways superior. This encounter between bureaucrats seeking to administer a vast social welfare program on behalf of the federal government and the African American beneficiaries of the program has produced documents of priceless value in documenting the experiences of former slaves, often in their own words. In Voices of Emancipation, we hope to communicate much more about what Civil War pension files reveal about the African American experience in the postwar period. Since the task is so large—nearly 180,000 black men served in the Union army, and just over half of them or their survivors applied for pensions—we hope other scholars will join us in this endeavor.

Donald R. Shaffer teaches U.S. history at the University of Northern Colorado in Greeley, Colorado. He is the author of After the Glory: The Struggles of Black Civil War Veterans (2004), which won the 2005 Peter Seaborg Award for Civil War Scholarship.

Elizabeth Regosin is associate professor of history at St. Lawrence University in Canton, N.Y. She is the author of Freedom's Promise: Ex-Slave Families and Citizenship in the Age of Emancipation (2002).

Note on Sources

The pension files of Civil War veterans are found in the Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Record Group 15, National Archives, Washington, D.C. Particular veterans' files are accessible through two pension indexes on microfilm: General Index to Pension Files, 1861–1934 (National Archives Microfilm Publication T288) and Organization Index to Pension Files of Veterans Who Served Between 1861 and 1900 (National Archives Microfilm Publication T289). The case files of family members are incorporated into the file of the soldier whose service qualified them for a pension.

The following are documents used in this article. Links to transcriptions are provided.

- Deposition of Dick Lewis Barnett, May 17, 1911; affidavit of Eliza Barnett, September 18, 1918; Pension File of Lewis Smith (alias Dick Lewis Barnett), Co. B, 77th U.S. Colored Infantry (USCI), and Co. D, 10th U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery.

- Deposition of Charles Washington, December 18, 1905; deposition of Emeline Anderson, Dec. 24, 1905; Pension File of Charles Washington, Co. E, 47th USCI.

- Deposition of Augustus Fletcher, October 26, 1902, Pension File of Charles Barnett (alias Barney alias Allen), Co. G, 92nd USCI.

- Deposition of Kitt Mitchell, June 9, 1903, Pension File of Kitt Mitchell, Co. K, 128th USCI.

- Letter of John L. Paine, Special Examiner, St. Louis, MO, to the Commissioner of Pensions, Washington, D.C., November 19, 1897, Pension File of Henry Taylor, Co. K, 102nd USCI.

- A. A. Aspinwall, Chief, Board of Review, to Chief, Special Examination Division, January 16, 1919; deposition of Mary Jane Taylor, May 13, 1919; Charles G. Townshend, Louisville, KY, to the Commissioner of Pensions, Washington. D.C., May 29, 1919; Pension File of Samuel Taylor, 45th USCI.

WPA Slave Narratives

The WPA Slave Narrative Collection comprises more than 2,000 narratives collected from ex-slaves in 17 states between 1936 and 1938. The original manuscript narratives are held by the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. However, these narratives were published in three multivolume sets from 1972 to 1979 by the Greenwood Press. See George P. Rawick, ed., The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography (1972); The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography, Supplement, Series I (1977); and The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography, Supplement, Series II (1979).

For more information on the WPA narratives, see Norman R. Yetman, "The Background of the Slave Narrative Collection," American Quarterly 19 (Fall 1967): 534–553; George P. Rawick, The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography, vol. 1, From Sundown to Sunup: The Making of the Black Community (Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Company, 1972), pp. xiii-xxi; John W. Blassingame, "Using the Testimony of Ex-Slaves: Approaches and Problems," in Revisiting Blassingame's The Slave Community: The Scholar's Respond, ed. Al-Tony Gilmore (Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Company, 1978), pp. 169–193; Paul D. Escott, "The Art and Science of Reading WPA Slave Narratives," in The Slave Narrative, ed. Charles T. Davis and Henry Louis Gates (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), pp. 41-58.

Black Military Experience in the Civil War

Once scarce, the historical literature on black soldiers in the Civil War is now extensive. Among the must-read books on African American troops are Dudley Taylor Cornish, The Sable Arm: Negro Troops in the Union Army, 1861–1865 (New York: Longmans, Green, 1956); Ira Berlin, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie S. Rowland, eds., Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861-1867; Series II: The Black Military Experience (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982); and Joseph T. Glatthaar, Forged in Battle: The Civil War Alliance of Black Soldiers and White Officers (New York: The Free Press, 1990).

Scholarly Books on African Americans That Use Civil War Pension Files

An increasing number of scholarly studies, especially those concerned with African Americans, make use of Civil War pension files. These works include: Laura Edwards, Gendered Strife and Confusion: The Political Culture of Reconstruction (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997); Leslie Schwalm, A Hard Fight for We: Women's Transition from Slavery to Freedom in South Carolina (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997); Noralee Frankel, Freedom's Women: Black Women and Families in Civil War Era Mississippi (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999); Elizabeth Regosin, Freedom's Promise: Ex-Slave Families and Citizenship in the Age of Emancipation (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2002); and Donald R. Shaffer, After the Glory: The Struggles of Black Civil War Veterans (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004).