Trading Gray for Blue

Ex-Confederates Hold the Upper Missouri for the Union

Winter 2005, Vol. 37, No. 4

By Michèle T. Butts

© 2005 by Michèle Butts

With the Union line leaking deserters like a sieve and the number of new recruits barely keeping pace with the thousands of veterans killed, wounded, or captured each week, the United States War Department in 1863 desperately needed a new source of manpower.

Caught between the demands of military commanders for more troops and state politicians for draft relief, President Abraham Lincoln in December permitted Confederate prisoners of war to enlist in the Union army to man the thinning Union lines.

Maj. Gen. John Pope, commanding the Department of the Northwest, added to the clamor as he begged for troops to garrison forts to be built along the Dakota frontier to protect steamboat passengers and emigrants from the Sioux. In August 1864 hard-pressed General-in-Chief Ulysses Grant sent Pope the only troops he was willing to spare for garrison duty on the Upper Missouri: the First U.S. Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

This regiment was composed of Confederate prisoners of war who had taken the oath of allegiance to the United States and enlisted for Federal service. For the next year, they bore the specific responsibilities of holding the Sioux in check while fostering peaceful relations, preventing illegal Indian trade, aiding overland emigrants, and gathering intelligence for Gen. Alfred Sully, commander of the District of Iowa.

On a broader scale, the First U.S. Volunteers' experiences provide a telescopic view of the critical issues to sweep the northern Plains and the nation for the rest of the 19th century. How could Native Americans and Euro-Americans live together in peace? How could the military and civilians overcome the harsh western environment? If the United States could reincorporate southerners into the Union, what sort of citizens would ex-Confederates make?

Butler "Galvanizes" Prisoners of War

Powerful Massachusetts Democrat Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler, commanding the Department of Virginia and North Carolina, was among the first to respond to the President's call for enlisted prisoners of war. From Camp Hoffman, Maryland, commonly called Point Lookout Prison, Butler recruited two regiments in 1864. Although the second, the Fourth U.S. Volunteers, was specifically recruited in the fall to garrison forts in the West, the First U.S. Volunteers were told as they enlisted between early January and the end of June that they would serve on the front lines in the South.

Following the President's explicit instructions, guards interviewed each prisoner individually and presented him with four choices: exchange, taking the oath of allegiance and enlisting in Federal military service, taking the oath and working on public works in the North, or taking the oath and being released to go home within U.S. lines. Despite prevailing official policies, Butler continued to make exchanges and to release hundreds of oath-takers to return to their homes within Union lines until after the First U.S. Volunteers were mustered into service. Their peers began calling them "Galvanized Yankees," an insulting term Confederates applied to individuals who took the oath of allegiance to cover themselves with Union blue, as they were released from the pen to live in their new camp.

As cause, comrades, and family fiercely competed for a Civil War soldier's loyalty, each of these "Galvanized Yankees" had his own reasons for renouncing his Confederate allegiance. War weariness, limited commitment to "the cause," Unionist sentiment, class resentments, and hardships at home shifting civilian loyalty away from the Confederacy all contributed to soaring desertions from the Confederate army. If loyalty to the Confederacy was forcing a soldier to fail in his primary responsibility to protect and provide for his family, enlistment in the First U.S. Volunteers promised an avenue of escape from the horrors of prison life, Union greenbacks, and protection for his loved ones within Union lines. Soldiers' letters indicate that they were well aware of their families' suffering and discussed taking the oath and enlisting in U.S. service with their families and friends.

Apparently, many of the men of Companies A, B, and C had avoided Confederate service as long as possible because they were married yeoman farmers with small children at home. Many of the men enlisting at Point Lookout did so along with their relatives or messmates. A high percentage of the enlistees were from the Upper South, where strong Unionist sentiment thrived. North Carolinians and Tennesseans rushed to enlist in the first three months in greater percentages than their presence in the entire regiment. Men from counties with low slave populations also volunteered more often for Union service. Some joined merely to escape the prison pen and seize the first opportunity to return home or to their Confederate unit.

Although Butler planned to use the enlisted prisoners of war in his Bermuda Hundred Campaign near Richmond, skeptical General Grant limited them to guard duty on the defenses of Norfolk and Portsmouth. Nevertheless, the First U.S. Volunteers successfully completed a few minor offensive missions before Grant ordered them to the Department of the Northwest to meet General Pope's demands for additional troops. As the regiment headed west, Pope ordered four companies to Minnesota, where they were to garrison forts along the Minnesota-Dakota frontier. He sent the other six companies, nearly 600 men, to build and garrison Fort Rice in Dakota Territory on the Upper Missouri.

Garrison Life in a Simmering Caldron

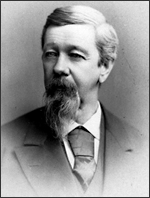

Commanding the Upper Missouri battalion and Fort Rice was Col. Charles A.R. Dimon. By catching General Butler's eye, the 23-year-old bookkeeper had risen from the rank of private in the Eighth Massachusetts Volunteer Militia when the war began. Rewarding Dimon's driving ambition and hard work, Butler appointed him first lieutenant and adjutant of the Thirtieth Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. After Dimon distinguished himself in the battles of Baton Rouge and Port Hudson, Butler promoted him to major in the Second Louisiana Volunteers, a regiment of former Confederates and Louisiana Unionists. When Dimon requested a position on Butler's staff, the general gave the loyal young go-getter command of the First U.S. Volunteers. Determined to make his family and his mentor proud, Colonel Dimon turned his "Galvanized Yankees" into a first-rate regiment.

After plying their way up the winding Missouri and marching the last 250 miles, the First U.S. Volunteers reached Fort Rice on October 17, 1864. As garrison of what Gen. Alfred Sully considered the most important post in the region, Colonel Dimon and his men recognized the importance of their mission's five goals. Their first priority was completion of the new fort's construction, which occupied most of the men until midwinter.

In mid-December, as the Dakota winter set in, temperatures hovered between 29 below and 34 degrees below zero, limiting guard duty to 15-minute intervals and halting construction details. Strangers to such extreme cold, the southerners suffered greatly, with several having frozen faces, feet, and fingers. Before spring arrived, the malnourished garrison was haunted by the specter of scurvy and other dietary deficiency diseases, which claimed the lives of 29 soldiers and racked the remainder. Despite the colonel's unauthorized issues of vegetables to the men, great fear arose that the garrison would not survive another winter on the Upper Missouri.

Before the First U.S. Volunteers settled into their new quarters and turned to the larger issues of Native relations, Indian trade, emigrant aid, and military intelligence gathering, the simmering anger of the Yanktonai and the Lakota Sioux boiled over. They correctly saw that the Euro-American wave moving upriver would destroy their way of life. They considered Sully's attack on the village at Killdeer Mountain the year before and construction of the military post on their choice hunting grounds and at their favorite crossing place on the Missouri a declaration of war. On Sunday, November 27, warriors demonstrating friendship suddenly attacked a detail and killed a herder near the Cannonball River. After vainly chasing the assailants until they vanished into the twilight, Colonel Dimon returned with the anger and frustration that would haunt him and the garrison throughout the coming year.

Repeatedly, Native American parties challenged the First U.S. Volunteers by simultaneously swooping down upon the post livestock, attacking loggers working in the woods, or by suddenly firing upon sentries and other work details. Before returning downriver, General Sully had left sage advice for the commander of the new fort. He admonished the garrison to foster good relations with Native people by sincerely listening to them, distributing rations to visitors, and promising good treatment to warring tribesmen who kept the peace. Despite Sully's parting survival tips to stay alert, be on the lookout for treachery, and send guard details with work parties, the Galvanized Yankees fell victim to 12 raids or incidents between late February and late May 1865. Seven of the enlisted prisoners of war and a popular young lieutenant were killed, and four men were seriously wounded by Native people in these encounters. A few casualties could have been avoided, but they were simply the price of military life on the Upper Missouri in 1864–1865.

Despite their constant fear of Native attack, the First U.S. Volunteers actively pursued the seemingly illusive goal of negotiating a peace agreement with the Lakotas and Upper Yanktonai. Their chief ally in this endeavor was the Yanktonai chief, Two Bears, whom Sully had convinced at Whitestone Hill in 1863 that peace was preferable to war. The short stocky leader with fierce, piercing eyes was very influential and very brave to venture into any sort of relationship with the strange aliens who were invading his homeland.

Although Dimon was not as convinced as Sully of the chief's loyalty, the young colonel obediently depended upon Two Bears as his main intermediary and informer among the Sioux. Sending his sons and other spies into camps upriver, Two Bears kept Dimon informed regarding the visits of anti-American Métí traders, raids being planned, and other intelligence. Upon Two Bears' assurance that Dimon was in earnest, Yanktonai Chief Black Catfish agreed in October 1864 to join Two Bears' camp of peace-seeking Sioux, trusting that the colonel would protect and be kind to his people. Over the coming year, several hundred Native Americans joined this peace faction of 150 lodges and proved to be loyal allies against war parties. Dimon invited Natives camped within a 40-mile radius to the post's Christmas feast and Fourth of July Celebration.

When Sully arrived in July 1865, nearly a thousand Native people were gathered to talk peace with him. Extremely suspicious and fearful of venturing near Fort Rice, the Natives had formed just the opposite opinion from what Dimon intended. They told Sully that the officers arrested "friendly" Native visitors and fired on friendly passers-by, mistaking them for warring tribesmen. When peacefully inclined Native Americans were followed by war parties, the garrison retaliated by shooting at the first Native person they saw. Dimon's execution of a Santee chief and his companion for leading four raids against the fort only increased the Natives' fear and fury. While Sully understood the young tenderfeet's ignorance of Native ways, the First U.S. Volunteers were undermining his peace initiative. When the garrison fired a howitzer to salute the general's arrival, a common fur trade practice, 130 lodges of Native Americans coming to see Sully fled in fear of an attack, illustrating how readily good intentions could be misconstrued on the Upper Missouri.

While isolated attacks had randomly occurred from Fort Randall to Fort Union, the northern plains exploded in the spring of 1865 as enraged Cheyennes and Lakotas exacted a bitter price for Euro-American invasion of their hunting grounds, destruction of their natural resources, and the deaths of their relatives at Killdeer Mountain and Sand Creek in 1864.

Less than a week after General Sully's Northwest Indian Expedition left Fort Rice for Devil's Lake in search of warring Sioux, 500 angry Lakotas, Cheyennes, and Upper Yanktonai swept in from the west, assaulting the fort from three sides on the morning of July 28. As in previous engagements, the First U.S. Volunteers raced from the fort to bravely stand their ground and then steadily advance against their attackers. Colonel Dimon's endless drills and strict discipline served them well in the close hand-to-hand fighting. The bastion guns' circular track, designed by one of the men, enabled them to rapidly fire across the battlefield in different directions. Sully recommended the impressive swivel design for use in all western forts. Field guns were run out of every gate to fire on groups of Natives as the battle raged.

After a 10-mile pursuit by Company G of the Sixth Iowa Cavalry and mounted infantrymen with more fierce hand-to-hand fighting, the warriors fled, disappearing a little past noon. Ten or more warriors were killed, and 10 or more were believed to have been wounded in the battle, while the garrison suffered 1 killed and 2 wounded. Most of the stolen stock was recovered after the running fight ended.

Proud of their successful defense, the First U.S. Volunteers would have resented the evaluation of a steamboat passenger who maintained that the Natives held the soldiers captive in the Upper Missouri forts. While the garrison's ability to keep the Missouri open for steamboats and protect traders and Indian agents were accomplishments in themselves in the face of Sioux warfare, Dimon and his men achieved far more. Although every defensive strategy he devised failed to curtail the raids, Colonel Dimon's consistent show of force upheld the flag during this critical period. Because of his strict training program, only seven of his men were killed by Native warriors on the Upper Missouri.

To offset the New England officers' ignorance regarding Native behavior, General Sully had ordered Dimon to seek the advice and assistance of two veteran Upper Missouri fur traders, Charles E. Galpin and Françoise La Framboise. "Frank" La Framboise had located the Indian camp at Whitestone Hill for Sully and served as post interpreter, but Galpin became the First U.S. Volunteers' most valuable asset.

Having lived in the Dakota country since 1839, Galpin was married to a highly intelligent Hunkpapa-Two Kettle woman named "Eagle Woman That All Look At." Because her father and her brother were important Lakota chiefs, Mrs. Galpin wielded great influence among her people. Together, they would convince Blackfoot Sioux, Brulé, Hunkpapa, Miniconjou, Oglala, Sans Arc, Two Kettle, and Yanktonai chiefs to participate in peace talks at Fort Rice in the fall of 1865. Of these, only 17 chiefs and 40 headmen of the peace faction traveled through an October snowstorm with Galpin and Lt. Col. John Pattee, acting post commander while Dimon was on leave, to negotiate peace treaties with U.S. commissioners at Fort Sully. Expressing their dislike for Colonel Dimon, the chiefs asked the commissioners to have Pattee, whom they had known for years, remain as commandant of Fort Rice. Within two years, the Upper Missouri tribes would sue for peace out of necessity, when the buffalo were gone, reducing them to subsisting on government largess.

Military vs. Civilian Control of Indian Trade

Dimon's diplomatic failings were overshadowed by his involvement in a no-win conflict with traders and the Office of Indian Affairs. Caught up in General Pope's attempt to regulate Indian affairs and trade, the colonel was determined to stop all trade with warring bands and to confiscate the stock of any trader operating among the Native people without the permission of U.S. military authorities as his orders required. Consequently, Dimon refused to recognize Charles Chouteau's Upper Missouri Outfit and its new owners, James B. Hubbell and Alpheus F. Hawley, because they were operating without Sully's permission. Based upon tips supplied by the Outfit's agent F. F. Gerard, the First U.S. Volunteers caught Hubbell and Hawley's agent selling whiskey, powder, and ball to Native Americans in violation of Pope's and Sully's regulations. Dimon's investigation led to the subsequent arrest of Hubbell and Hawley's partner and other agents at Fort Berthold for illegally selling arms and ammunition to warring Natives.

For unknown reasons, none of the incriminating evidence gathered by Dimon's officers was considered when an official tribunal met to examine the case of one company agent. As a result, he was released, and all charges were dropped. The Office of Indian Affairs had added to the confusion by granting three different companies trading licenses on the Upper Missouri. As Pope demanded, Dimon refused to permit any traders to operate until they presented him with official licenses endorsed in writing by General Sully.

Beginning with the arrival of Chouteau's Yellowstone in May 1865, Dimon stopped every steamboat bound upriver and searched it for whiskey, arms and ammunition, and Indian trading goods. The aggressive commandant believed that Pope's orders authorized him to seize all suspicious cargoes and to send a commissioned officer upriver to prevent any trading with Native Americans except by permission of a military commander. While a detail boarded every boat between Forts Union and Benton to prevent illegal trading, Capt. Benjamin (elder brother of the colonel) Dimon's Company K at Fort Berthold and Capt. William Upton's Company B at Fort Union carefully examined and guarded every boat passing their posts. When James Hubbell informed Sully in late May of Colonel Dimon's clash with Chouteau aboard the Yellowstone, the embattled general, suffering from his own political problems, ordered Dimon to stop searching steamers and interfering with traders licensed by the Interior Department.

In a more direct challenge to Indian officials, Colonel Dimon and his officers were interfering with Indian agents as the soldiers tried to prevent graft and to keep annuities from reaching tribes at war with the United States. The resulting flak fell on General Sully and contributed to his removal as commander of the District of Iowa at the war's end. Crushed by Sully's reprimand, Colonel Dimon rescinded his previous orders and restricted his operations to Fort Rice. Within five years, the Office of Indian Affairs would expect-and Pope would require-Army officers to actively prevent and disrupt illegal Indian trade.

Further outraging Chouteau, Hubbell and Hawley, and other steamboat passengers, Dimon conducted a loyalty program. Like Sully, the officers at Fort Rice believed that all the men heading upriver during the Civil War were rebels, draft dodgers, or deserters. When unruly civilians wintering at the post rebelled against Dimon's regulations, the colonel proclaimed martial law, confiscated their arms and ammunition, and began requiring everyone passing the fort to register and to take an oath of allegiance to the United States. Before Sully countermanded Dimon's orders, the First U.S. Volunteers amassed personal information on 516 travelers who visited Fort Rice in 1865. Dimon maintained that he had administered oaths of allegiance aboard steamboats only upon the specific request of the captain or passengers.

First U.S. Volunteers Aid Emigrants and Gather Intelligence

Although Dimon's loyalty program rubbed some travelers the wrong way, the First U.S. Volunteers fulfilled their third objective far better than public opinion indicated. Protecting citizens passing up and down the Missouri was difficult, but the garrison notified travelers of the possible location of war parties and provided a safe haven for emigrants and steamboats. When a party of starving miners from Idaho reached the fort in December 1864 after Native Americans had taken their clothing, firearms, and provisions, the garrison fed and clothed them and outfitted them for their journey downriver. Dimon ordered a rescue party to bring in an injured member of the party, who was barely alive when the detail found him.

In June 1865 Colonel Dimon negotiated a trade with Miniconjou chiefs of two American horses for Sarah Morris, who had been captured by the Cheyenne in Colorado six months earlier. While Mrs. Morris recovered from her ordeal in the hospital, the officers chipped in to buy her clothing and pay her passage to her father's home in Indiana. As steamers plied their way past Fort Rice, the garrison provided them with food, supplies, weapons, and ammunition and assisted them in every way possible. If one became stuck on a sandbar within reach of the fort, a detail was dispatched to guard the steamboat until it floated out or was towed free.

Throughout the fall, winter, and spring of 1864–1865, Dimon meticulously carried out the garrison's fourth mission of gathering intelligence and conducting reconnaissance for General Sully. During a January trip to Fort Sully, the colonel charted in detail a new winter route between the forts. In March, Dimon subtly gleaned from Galpin a thorough first-hand description of the Cheyenne River country from Fort Pierre to the Powder River for Sully. General Sully was secretly preparing for General Pope's spring Powder River campaign, but an isolated Native raid in Minnesota brought orders to march on Devil's Lake instead. To keep Sully regularly informed of the Native people's locations and activities, Dimon sent Native allies into the camps upriver and to the west. The colonel relayed downriver their reports of impending raids, illegal trading, and the numbers favoring peace and war within each camp as well as news brought by other informants.

"How Long 'til Muster Out, How Long?"

On July 24, 1865, the weary men's spirits soared as the mail brought news of the impending muster-out of all volunteer regiments. When Colonel Dimon received a letter stating that they would not be mustered out, the First U.S. Volunteers' battalion unity—born in Native warfare, the bitter Dakota winter, and the horrors of scurvy—began to disintegrate. As the officers' resentment toward Dimon grew, they told the men that the colonel had persuaded General Pope to keep them in service. Consequently, discipline and order at Fort Rice deteriorated steadily in September 1865, while Dimon was concluding his medical leave and heading to his new command in the Department of Kansas.

A series of incidents revealed the breakdown of discipline and disrespect for Dimon, who appeared to have abandoned them. Many deserted—as men chose home or the gold fields over another winter of death at Fort Rice. Eleven percent of the command had died the previous winter, and all who survived still suffered from scurvy's lingering effects.

Like volunteer troops elsewhere, the First U.S. Volunteers believed that they had earned the right to go home—especially since their former prison comrades had been released in the spring. The ex-prisoners of war had requested through channels to be mustered out when news of Appomattox reached the Upper Missouri, only to be turned down by the War Department. As soon as they heard they were going to be mustered out after all, the First U.S. Volunteers returned to their duties and prepared everything for transfer.

When Dimon returned by order of Maj. Gen. Grenville Dodge on October 9, he found few friends at Fort Rice, but he quickly reestablished discipline and led the battalion downriver to Fort Leavenworth. The Dakota Battalion mustered out on November 27, 1865. Although some headed for the gold fields, most returned home to their families in the South.

Despite their short tenure on the Upper Missouri, the First U.S. Volunteers left an important legacy. From their suffering and needless deaths, the Army eventually learned to supply western garrisons months in advance with fruits and vegetables and buffalo clothing for the severe winters. Dialogue was opened with Yanktonai and eastern Teton leaders who could foresee having to share their country with Euro-Americans. Native American annuities were protected from illegal graft, and illegal trade was curtailed. Northwestern commerce and emigration was protected and encouraged. More important than the insight they shed on the nature of civil war, Native–Euro-American relations, and frontier development, the U.S. Volunteers provide a vivid picture of the rebirth of the United States after the Civil War. On the Upper Missouri, the First U.S. Volunteers demonstrated that Northerners and Southerners could live peaceably and work together toward common goals.

Controversial Col. Charles Dimon's devotion to duty and to his men's welfare enabled him to overcome physical, if not political, obstacles to establish a beachhead of Euro-American civilization on the Upper Missouri. While his lack of diplomacy and experience prevented fulfillment of General Pope's vision, Dimon fulfilled most of the objectives with which he was entrusted, and in fairness no one else could have established a general peace on the Upper Missouri in 1864–1865. Perhaps his greatest contribution was his encouraging the First U.S. Volunteers to identify with the United States and their role in national expansion.

The larger story of the First U.S. Volunteers is told in Michèle Butts's book Galvanized Yankees on the Upper Missouri: The Face of Loyalty (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2003).

Michèle Butts, is professor of history at Austin Peay State University in Clarksville, Tennessee. Her research focuses on U.S. military history, Native American history, and the American West. She is currently working on a history of Merrill's Marauders.

Note on Sources

In researching the First U.S. Volunteers, many primary sources were consulted. The National Archives in Washington, D.C., holds the regimental books, papers, and records of the regiment housed among the Records of the Adjutant General's Office, 1780's–1917 (Record Group 94) and the records of the Departments of the Missouri and Northwest and the Military Division of the Missouri within the Records of United States Army Continental Commands, 1821–1920 (Record Group 393).Personal information on the prisoners of war who enlisted in the regiment was found in the Selected Records of the War Department Relating to Confederate Prisoners of War, 1861–1865 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M598). Annual Reports of the U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs and the Secretary of War and relevant House and Senate Executive Documents were found in the U.S. Serial Set. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies was an important source of official correspondence and military reports. Of great importance as well were the Charles A.R. Dimon Papers and sources within the Coe Collection at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library of Yale University. A wealth of secondary sources provided background and connecting information.