Old Ironsides: Warrior and Survivor

An interview with author David G. Fitz-Enz

Spring 2005, Vol. 37, No. 1

By Ellen Fried

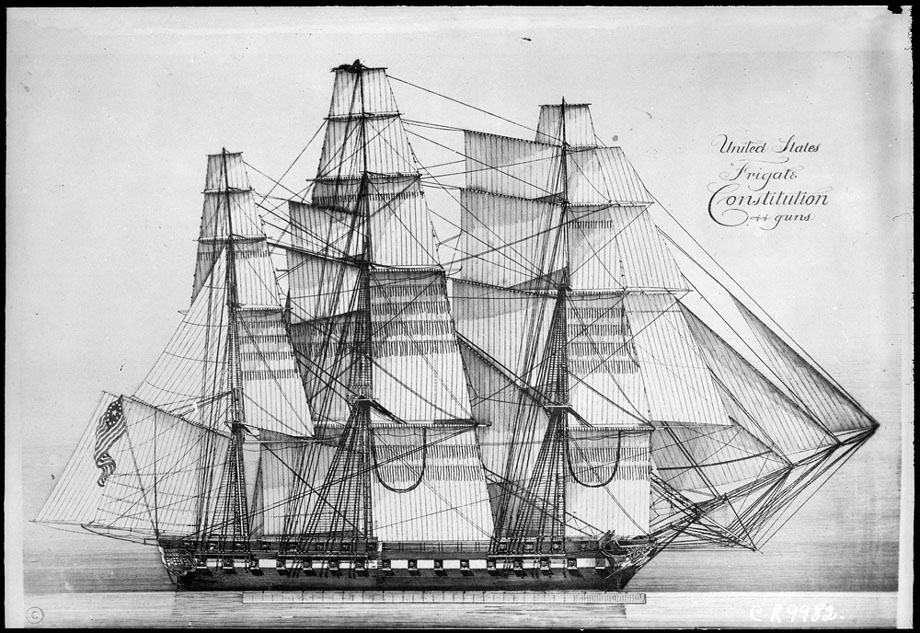

The USS Constitution is the oldest commissioned warship still afloat. Constructed in Boston in 1797, she was one of the United States Navy's first men-of-war. Her exploits during the War of 1812 made her the stuff of legend. Americans fought on her behalf to save the great ship from destruction. Today, she is moored in Boston Harbor, a floating museum of naval history and an enduring tribute to the Age of Sail.

In his new book, Old Ironsides, Eagle of the Sea, Col. David G. Fitz-Enz tells the full story of the celebrated warship, from the architect's vision through battle victories to recent restoration efforts.

Fitz-Enz is a retired Army officer and the author of two previous books, Why a Soldier? and The Final Invasion. He spoke with Prologue from his home in Onchiota, New York.

How does a career soldier come to write a book on naval history?

My first book was a memoir about my time as a Signal Corps officer in Vietnam. Then I got involved in writing a PBS documentary about the Battle of Plattsburgh, a decisive battle in the War of 1812. I had thought it was an Army battle, but as it turned out, it was really a naval battle—the town sits on Lake Champlain.

I ended up with reams of fascinating, virtually unknown information about the battle of Plattsburgh—more than would fit into a documentary. So I wrote a book.

The book got the publisher interested in naval history. He suggested that I write a book about the USS Constitution, a warship from the same time period.

How did you begin your research?

I spent the first year just learning how ships sailed.

In the days of sail, you didn't necessarily go where you wanted to go. You went where the winds allowed you to go to. If the winds had changed on Lake Champlain in August 1814, we would have lost the War of 1812. But I had to investigate ships to understand that—to understand the factors involved in winning or losing battles.

Old Ironsides, Eagle of the Seas is really three books in one. The first is about how sailing ships were built and how they worked. The second is about why we needed a navy. The third is the story of the Constitution itself. I didn't plan it that way—I planned to just write about the ship. But I realized I couldn't do that without first understanding how such ships operated—and why we needed them.

Why did we need a navy?

In the early years of this country, there was no U.S. Navy. The Continental Navy had been disbanded in 1784. Many people were opposed to having a navy; they thought it was too expensive.

But we were paying a lot of tribute to pirates in the Mediterranean to keep them from capturing our ships and enslaving our crews. George Washington said this is no way to run a nation; we need to be able to defend ourselves and our commerce. So the very first ships of the U.S. Navy—including the USS Constitution—were built and launched in the late 1790s.

The Constitution fought first against French privateers and then against Barbary pirates. The War of 1812 was her third conflict, and it was the one in which she distinguished herself.

What was significant about the War of 1812?

The War of 1812 was when we came into our own as a sovereign nation.

The British were disregarding our sovereignty; they were harassing our ships and impressing our sailors into their navy. So, in the spring of 1812, the sovereign nation of the United States of America declared war on Great Britain because of "intolerable grievances."

Now, the British Royal Navy was the strongest in the world at that time. They had 600 man-of-war ships; we had 20. Really, the government of the United States should have been prosecuted for starting this war; it was a crime. We should have been utterly wiped out by the British.

But we weren't. We prevailed against incredible odds. The War of 1812 was probably the greatest chapter in our history—and the frigate Constitution played a central role in that struggle.

What was distinctive about the Constitution?

The Constitution was a unique item of war. She fit a niche discovered by her designer, Joshua Humphreys. He realized that, for a long time, our navy would be inferior in numbers to the navies of Europe, so we needed to make our few ships as formidable as possible.

Now a frigate was a fifth-rate ship out of the six rates of ship. It was a comparatively small ship. But Humphreys' frigates were unique in that they were bigger than other frigates. And they were also faster, because he gave them a more streamlined hull.

They were so big that they could defeat any other frigate, and they were so fast that they could outrun any more powerful ship. In those days, it was not considered cowardly to run from a battle with a ship of war of greater size; it was regarded as prudent.

How did the Constitution get the nickname "Old Ironsides"?

It was in the great naval battle where the Constitution captured the British ship Guerriere. A sailor on the Guerriere saw 18-pound British cannonballs bouncing right off the hull of the Constitution. He exclaimed, "Huzza, her sides are made of iron!"

But they weren't made of iron. They were made of oak.

What made the hull so impenetrable?

For one thing, it turns out that American oak is denser than English oak. That wasn't realized at the time.

But there was another factor as well. When Humphreys constructed the Constitution, he knew she was going to take a lot of pounding. So he put the ribs on the sides of the ship only four inches apart. On conventional warships, the ribs were eight to ten inches apart.

Humphreys' frigates were big, fast, and strong. The British had nothing like them.

How did the Constitution get her other nickname—"Eagle of the Sea"?

That comes from the next phase of her story—the story of the effort to save her.

It was 1830. The Age of Sail was waning, and the Age of Steam was getting under way. The Navy was just letting the old sailing ships deteriorate.

An unknown 22-year-old law student named Oliver Wendell Holmes published a poem about the Constitution's fate in a Boston newspaper. The second stanza ended with the words, "The harpies of the shore shall pluck / The eagle of the sea!"

Newspapers around the country picked up the poem. It was the beginning of the nation's interest in saving the ship. Old Ironsides stopped being the Navy's ship and started being the people's ship—and it has remained so to this day.

It has become a national monument—as much so as the White House or Fort McHenry. To me, it's the only movable monument in the country.

What parts of the Constitution's story did you find in the National Archives?

I uncovered evidence of both the ship's naval history and the efforts to restore her.

Archivist Rebecca Livingston, an expert on naval warships, and her colleague, Kim McKeithan, were just terrific. They sat down with me and listened to what I was trying to do and steered me in the right direction.

We found some amazing things—such as the original sail plan from 1797. I'd been told by several naval authorities that the sail plan no longer existed. But there it was, in the National Archives. Now, the sail plan is really important—that's the "engine" of the ship. I also discovered descriptions of naval encounters that I found nowhere else.

Becky also led me to correspondence about the efforts to save the Constitution. There were some really unique things documented there, from campaigns by historical societies in the 1800s to efforts by schoolchildren in the 20th century. The attempt to save the ship goes way back.

What do you think is most important about the Constitution?

To me, the most important thing about the ship is her survival. She's the only ship in the world still in the water after 200 years. The framing inside her is still original. Just think of it—those trees were cut in 1795 and 1796.

What do you hope your readers take away from this book?

What I would most like readers to take away is an understanding of the importance of the Navy. Without the Navy, this nation would not be a superpower.

And that's saying a lot, coming from a career Army officer.