LBJ Champions the Civil Rights Act of 1964

Summer 2004, Vol. 36, No. 2

By Ted Gittinger and Allen Fisher

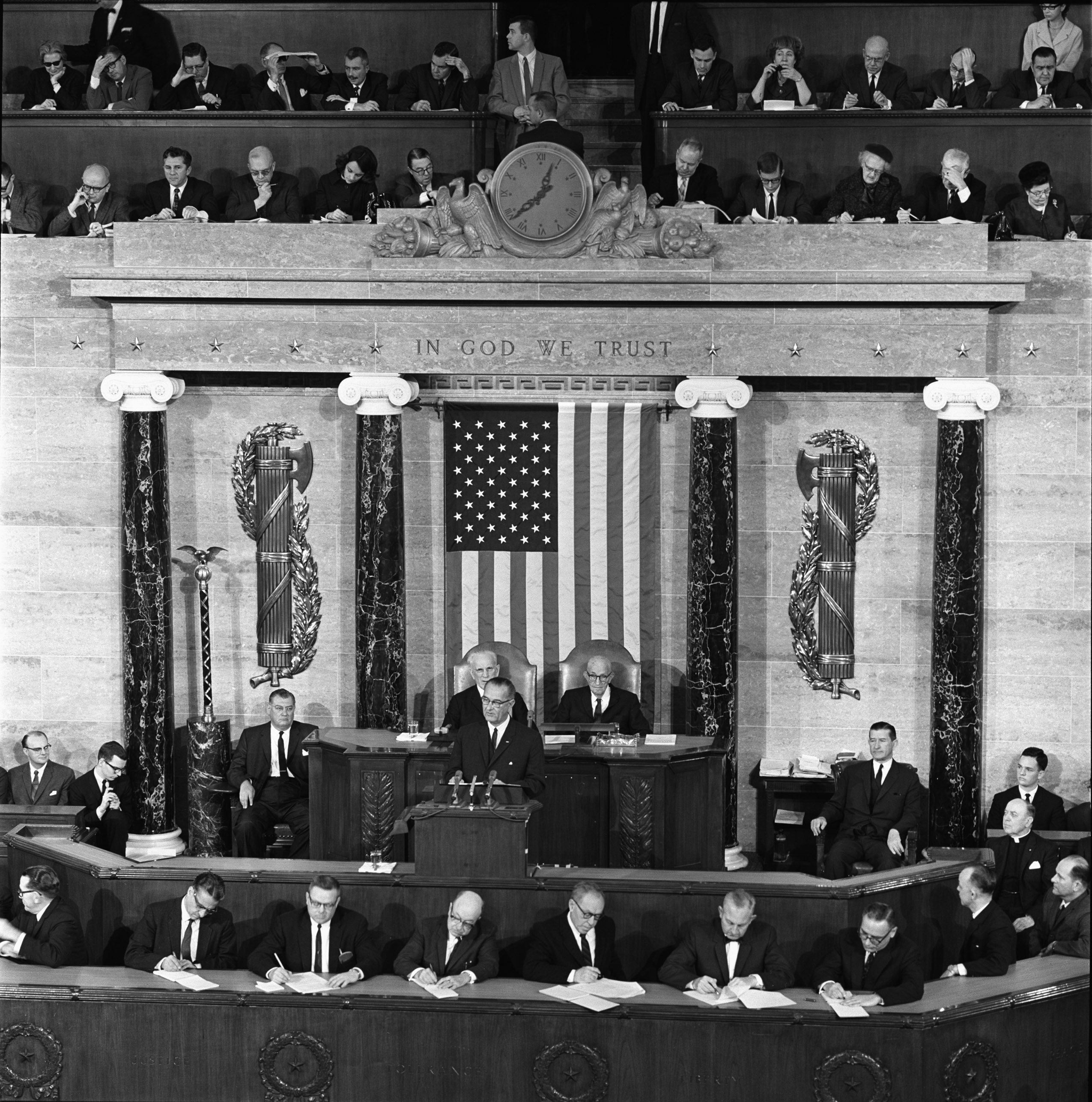

Just five days after John F. Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963, Lyndon B. Johnson went before Congress and spoke to a nation still stunned from the events in Dallas that had shocked the world.

Johnson made it clear he would pursue the slain President's legislative agenda—especially a particular bill that Kennedy had sought but that faced strong and vehement opposition from powerful southern Democrats.

"No memorial oration or eulogy could more eloquently honor President Kennedy's memory than the earliest possible passage of the civil rights bill for which he fought so long," Johnson told the lawmakers.

Then, serving notice on his fellow southern Democrats that they were in for a fight, he said: "We have talked long enough in this country about equal rights. We have talked for one hundred years or more. It is time now to write the next chapter, and to write it in the books of law."

That chapter became the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Forty years ago, Johnson set out to do what he had done in 1957 and 1960 as Senate majority leader—steer a civil rights bill through a Congress controlled to a great extent by southern Democrats who so strongly opposed it. But he was no longer majority leader and could not buttonhole wavering members in the cloakroom or do horse-trading with them to get what he wanted or promise rewards or punishments.

This is the story of how Lyndon Johnson set the stage for this legislation years before and how he choreographed passage of this historic measure in 1964—a year when the civil rights movement was rapidly gaining strength and when racial unrest was playing a role in the presidential campaign.

The story is often told, but this account is supplemented with details discovered in recent years with the opening of Johnson's White House telephone recordings and with excerpts from the oral history collection at the Lyndon B. Johnson Library in Austin, Texas.

It begins in 1957, with Johnson as Senate majority leader, engineering passage of the 1957 Civil Rights Act, a feat generally regarded as impossible until he did it.

"To see Lyndon Johnson get that bill through, almost vote by vote," said Pultizer Prize–winning LBJ biographer Robert Caro, "is to see not only legislative power but legislative genius."

One key to Johnson's success was that he managed to link two completely unrelated issues: civil rights and dam construction in Hells Canyon in the Sawtooth Mountains of America's far northwest. Western senators were eager for the dam, which would produce enormous amounts of electricity. For years the advocates of public power and private power interests had fought to determine whether the dams would be built by government or private companies.

Those favoring public power were generally liberals from the Northwest states; they were liberal on civil rights as well, but they had no large numbers of African American voters in their states to answer to, so a vote against civil rights would not hurt them very much. LBJ brokered an agreement that traded some of their votes to support the southern, conservative position favoring a weak civil rights bill. In return, southerners would vote for public power at Hells Canyon.

A key issue in the 1957 bill, as originally written, was its provision that certain violations of it could be tried in court without benefit of a jury. But, as Senator Hubert H. Humphrey recalled, the issue of whether to have jury trials included in the 1957 bill was a terribly difficult matter even for many of the liberals. Humphrey said his populist background had emphasized the importance of jury trials, yet he realized that southern juries would never convict any white person accused of violating a civil rights law.

Nevertheless the liberals took the hard line, that there should be no jury trials, and that violations of the law should be subject to criminal contempt proceedings, not civil contempt. Humphrey also remembered that LBJ had convinced Senator John F. Kennedy to vote for jury trials, and that it never seemed to hurt Kennedy's liberal credentials. Jury trials were included in the final act.

As a result, the 1957 Civil Rights Act was nearly toothless legislation—which is one reason it was able to win Senate approval. Still, it had significance. George Reedy, an assistant to LBJ for many years, anticipated later authors with his evaluation of the 1957 Civil Rights Act, when he wrote in 1983:

This is the point which has probably caused the most confusion among students of the political process. Their mistake has been to examine the 1957 bill solely on the basis of its merits. The more important reality is that it broke down the barriers to civil rights legislation and made possible more sweeping acts which followed later. . . . [T]he Senate is an on-going body and its acts must be analyzed not just in terms of what they do but how they pave the way for doing other things. [Emphasis in the original.]

In his oral history, Representative Emanuel Celler of New York, then chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, who wrote the 1957 bill, may have overstated his case when he said that the finished Civil Rights Act "was a revolutionary bill . . . . it was worth the compromise. . . . I think the liberals were pretty jubilant that we had this breakthrough."

Johnson also engineered Senate passage of the 1960 Civil Rights Act, which again was nearly toothless. Both acts primarily focused on voting rights, and neither provided realistic means of enforcement. But they placed the civil rights issue on the legislative agenda and foreshadowed future battles for broader, tougher legislation.

The Kennedy administration took office in 1961 as national sentiment in favor of stronger civil rights legislation, with means of enforcement, was growing.

President Kennedy, however, was loath to ask the Congress for strong legislation on the issue. Although he was personally sympathetic to the plight of African Americans, his political instincts warned against taking action.

Then came one of those events that forces the hand of a cautious leader.

On May 2, 1963, a horrified country watched on television as the public safety commissioner of Birmingham, Alabama, T. Eugene "Bull" Connor, and his policemen and firemen descended on hundreds of African American marchers, including schoolchildren, with attack dogs, nightsticks, and fire hoses.

In response to the resulting national uproar, on June 11 Kennedy went on national television to announce that he was sending a tough civil rights bill to the Congress. A few hours later, Medgar Evers, director of the Mississippi National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), was murdered in the driveway of his house.

Kennedy now began a very public lobbying campaign, pressing various private organizations to desegregate and demonstrate support for his bill. This was sure to arouse the enmity of powerful southerners in the Democratic-controlled Congress, and that had serious implications: Southern Democrats chaired twelve of eighteen committees in the Senate and twelve of twenty-one in the House. It meant putting the President's entire legislative agenda at risk.

One part of that agenda was the President's proposed tax reduction, which he wanted badly. He believed that it would stimulate the economy and thus have a salutary influence on the 1964 election. But it needed time to do its work, so it had to be passed soon. That would be difficult. Congressional conservatives already disliked the bill on its face because it would create deficits.

If Kennedy were to insist on a civil rights bill, it could well tie up the Congress in a wrangle that might keep the tax bill from ever reaching to the House floor.

Kennedy decided to take the chance, but he had nagging doubts. He asked his brother Robert, "Do you think we did the right thing by sending the legislation up? Look at the trouble it's got us in." They had no choice, the attorney general responded, the issue had to be faced up to—and right away.

On June 26 the House Judiciary Subcommittee No. 5 began hearings on the civil rights bill. The subcommittee was dominated by liberals and chaired by Celler, who also headed the full committee, which was more balanced in membership. It was expected that the bill would not have much trouble in the subcommittee, and in August, Celler announced that they would begin closed sessions to "mark up" the bill into final form.

But President Kennedy had secretly asked Celler to hold up the civil rights bill until the tax bill was out of the House Ways and Means Committee, chaired by Representative Wilbur Mills of Arkansas. If the civil rights bill came out first, Kennedy feared that Mills would retaliate by killing the tax measure—and Mills, a fiscal conservative, disliked the tax cut on principle in any case. Even if Mills did not quash the bill, conservatives on the Senate Finance Committee were perfectly capable of doing so.

Meanwhile, the pressure for action on civil rights continued to grow. The biggest lobbying effort ever seen in the nation's capital, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, took place in the summer of 1963.

There had been considerable worry in the administration that the event would turn ugly, perhaps degenerate into a massive riot. It had happened at other marches. A. Philip Randolph, president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and a chief organizer of the march, recalled meeting with President Kennedy and Vice President Johnson on that question:

The whole question involved there was the correctness of the strategy of staging a march as big as this in Washington. And how it could be controlled, so that it would not get out of hand. . . . President Kennedy was a bit worried about it. . . .

One of the problems was the matter of spilling over into the streets and becoming involved with violence. Now, our position was that we could not guarantee what would happen, but we had taken the precautions to plan the march [in detail], with a view to avoiding violence.

On August 28, nearly a quarter of a million people gathered around the Reflecting Pool on the National Mall to listen to Martin Luther King, Jr., declare, "I have a dream." There was no violence.

On September 10 the House Ways and Means Committee at long last approved the tax cut bill, thus clearing the way for Celler's subcommittee to mark up the civil rights bill—not that the tax bill was out of the woods by any means. It still had to go to the House Rules Committee, chaired by powerful archconservative "Judge" Howard W. Smith, a Democrat from Virginia, where it would be scheduled for consideration by the full House—unless Smith killed it first.

Then, external events altered the congressional schedule.

On September 15, four little African American girls were killed in Birmingham when a bomb exploded under the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. There was enormous national outrage, and the liberals on the Celler subcommittee responded by introducing amendments to the civil rights bill to strengthen it far beyond what William McCulloch, the leading moderate Republican member, thought could be voted out of the House.

Chairman Celler, however, accepted the amendments. His strategy was to report out of the subcommittee a bill so strong that it could not win approval in the full committee. Then Celler would work for compromise and get most of what he had wanted in the first place.

The stronger version of the bill was reported favorably to the full committee on October 2, and the political infighting began in earnest.

Lawrence F. O'Brien, President Kennedy's and later President Johnson's chief of liaison with the Congress, recalled it this way:

[Y]ou had a battle on two fronts simultaneously. You had a battle with the conservatives on the committee, the southern Democrats, conservative Republicans, but you had just as tough a battle with the liberals. Their position was the old story of the half loaf or three-quarters of a loaf, and [now they were saying] "we'll settle for nothing less [than the whole loaf.]" . . . We shared their views, and we'd love to do it their way.

We were accused by some of being weak-kneed but, my God, are you going to have meaningful legislation or are you going to sit around for another five or ten years while you play this game? Those liberals sat around saying, "No, we won't accept anything but the strongest possible civil rights bill, and we won't vote for anything less than that." To kill civil rights in that Judiciary Committee was an appalling possibility! And it was not only a possibility, it came darn close to an actuality.

The Kennedy administration had wanted to get past the civil rights fight by the end of 1963, so as not to have the struggle continue into the following election year. That hope had by now gone by the boards, even if the committee reported favorably on the bill, and promptly. It took until November 19 for the measure to make it to the Rules Committee to be scheduled for consideration on the floor of the House. And Rules Committee Chairman Smith was certain to seek ways to stifle the bill first.

But at 12:30 p.m., on a sunny November 22 in Dallas, everything changed.

Jack Valenti, a top aide to Johnson, gave this account of what happened on the night of John Kennedy's assassination:

Twelve hours later, LBJ was in his home in Spring Valley, three trusted friends by his side—the late Cliff Carter, Bill Moyers, and myself. He lay on his huge bed in his pajamas watching television, as the world, holding its breath in anxiety and fear, considered that this alien cowboy was suddenly become the leader of the United States.

That night he ruminated about the days that lay ahead, sketching out what he planned to do, in the almost five hours that we sat there with him. Though none of us who listened realized it at the time, he was revealing the design of the Great Society. He had not yet given it a name, but he knew with stunning precision the mountaintop to which he was going to summon the people.

In his address to the joint session of Congress on November 27, President Johnson gave notice that he wanted quick action on both civil rights and the tax bill:

I urge you again, as I did in 1957 and again in 1960, to enact a civil rights law so that we can move forward to eliminate from this Nation every trace of discrimination and oppression that is based upon race or color. There could be no greater source of strength to this Nation both at home and abroad.

And second, no act of ours could more fittingly continue the work of President Kennedy than the early passage of the tax bill for which he fought all this long year. This is a bill designed to increase our national income and Federal revenues, and to provide insurance against recession. That bill, if passed without delay, means more security for those now working, more jobs for those now without them, and more incentive for our economy.

On November 29, the day after Thanksgiving, Johnson met with Roy Wilkins, executive director of the NAACP, to talk about the civil rights bill.

"He was asking us if we wanted it, if we would do the things required to be done to get it enacted," Wilkins recalled. "He said he could not enact it himself. He was the President of the United States. He would give it his blessing. He would aid it in any way in which he could lawfully under the Constitution, but that he could not lobby for the bill. And nobody expected him to lobby for the bill, and he didn't think we expected him to lobby for the bill. But in effect he said—and he didn't use these words—'You have the ball; now run with it.'"

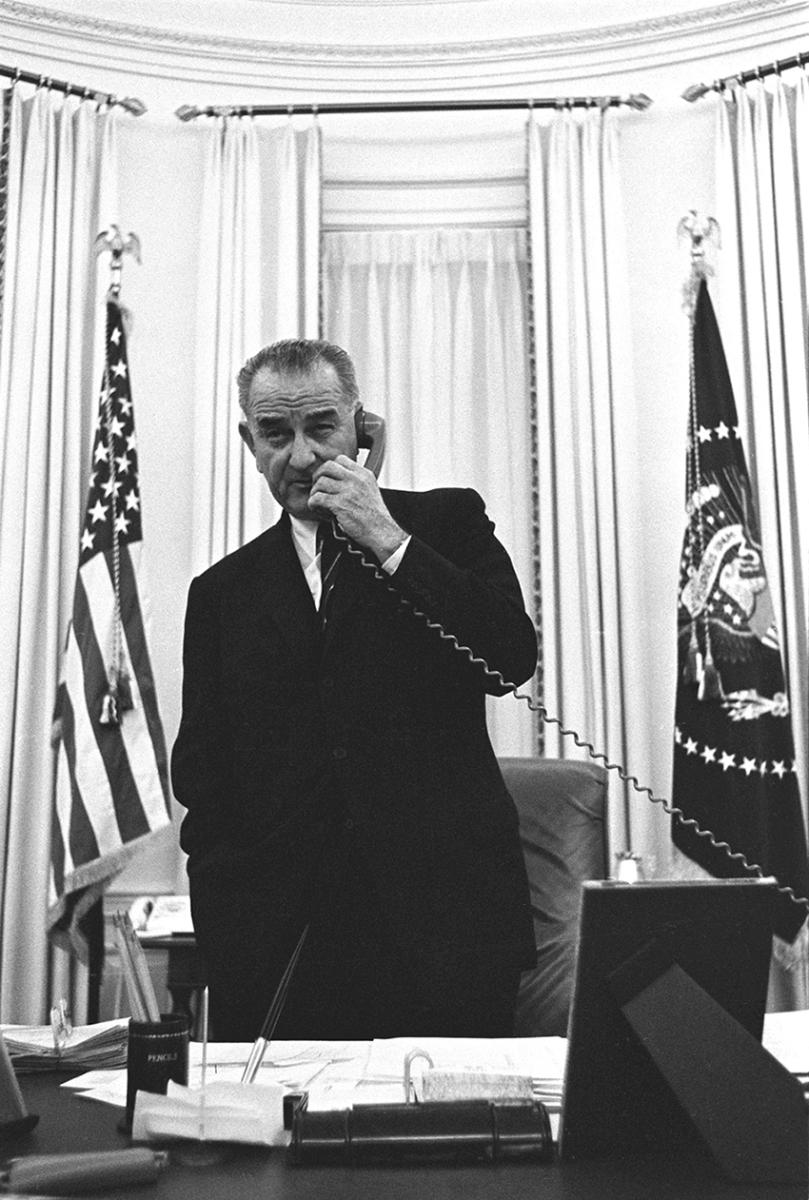

This was Johnsonian hyperbole. Given LBJ's legendary record for "lobbying" members of Congress, the President could only have meant that he couldn't get civil rights passed by himself. In fact the President had been on the phone that same day with the minority leader of the Senate, Everett Dirksen, the Illinois Republican.

"If Congress is to function at all and can't pass a tax bill between January and January, why, we're in a hell of a shape. . . . They ought to pass it in a week," Johnson told Dirksen. "Then . . . every businessman in this country would have some confidence. . . . We've got an obligation to the Congress. And we've just got to show that they can do something, because we can't pass civil rights. We know that."

Johnson meant that the southern senators were sure to filibuster against the civil rights bill, and there weren't yet enough votes to shut off the debate.

Meanwhile, civil rights was mired in the House Rules Committee, where Judge Smith would not give it a hearing. On December 2, Johnson called Katharine Graham, publisher of the Washington Post, to enlist her editors in pressuring representatives to sign a discharge petition. That would bring the bill out of the Rules Committee. Many representatives were against a discharge petition on principle, believing that it undermined the committee system. LBJ suggested that the Post run articles arguing "every day, front page . . . [about] individuals: 'Why are you against a hearing?' Point them up, and have their pictures, and have editorials, and have everything else that is in a dignified way for a hearing on the floor."

To persuade Republicans to sign the petition, LBJ continued:

We've only got 150 Democrats; the rest of them are southerners. So we've got to make every Republican [sign]. We ought to say, "Here is the party of Lincoln. Here is the image of Lincoln, and whoever it is that is against a hearing and against a vote in the House of Representatives, is not a man who believes in giving humanity a fair shake. . . . Now if we could ever get that signed, that would practically break their back in the Senate because they could see that [this movement] here is a steamroller."

Articles critical of Smith and those who were cooperating with him began to appear in the Post.

Now, for once, Chairman Smith faced a serious challenge to his power to kill a bill that he disliked. An unlikely coalition had come together on the Rules Committee, of liberal Democrats, moderate and liberal Republicans, and a single conservative midwesterner, Republican Clarence Brown of Ohio. Brown controlled enough GOP votes to force Smith's hand by threatening to wrest control of the committee from him. Rather than face that loss of power and resulting humiliation, Smith agreed to hold hearings on civil rights in early January. There would be no need for a discharge petition.

Smith did not give up without a fight. His committee held hearings for three weeks, but in the end the chairman asked for the votes to be counted. The bill passed, 11-4.

Meanwhile, the nation's clergy had begun to throw its weight behind civil rights. The National Council of Churches would eventually spend $400,000 in its lobbying efforts. Historian Robert Mann wrote, "During the House debate, the gallery sometimes seems to overflow with ministers, priests, and rabbis—most of them voluntary watchdogs, or 'gallery watchers,' who tracked the votes and other activities of House members."

But Howard Smith had one last arrow in his quiver—perhaps "bombshell" would be a better term. During the debate on the House floor on Title VII, the equal employment part of the bill, the Virginian offered an amendment stating that not only should discrimination in employment based on race, creed, color, and national origin be illegal, as Title VII then stated, but distinctions based on sex as well. The House was thunderstruck. Now the question was not only where did the predominantly male Representatives stand on the question of race, but where did they stand on women?

Certainly Smith hoped that such a divisive issue would torpedo the civil rights bill, if not in the House, then in the Senate. But the new-found strength of the civil rights movement trumped Smith's ace. The House gulped, then accepted Smith's amendment. On February 10, 1964, the bill passed the House 290 to 130.

Despite this progress, LBJ was pessimistic. In that kind of mood he would vent to anybody who was handy—he once vented to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs about a civil service pay bill—and on December 20 he complained to Jim Webb, head of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration:

If you don't pass the civil rights bill, and you don't pass the tax bill, you can't do it. And I don't see any hope for passing either one right now. That's my honest judgment.

And the civil rights bill is going to be out of the House . . . and they'll [the southern senators] start filibustering. [Senator Richard] Russell's got the votes, where you cannot put cloture on. So the tax bill'll get behind the civil rights bill. And your civil rights'll be defeated, and by that time, it'll be too late for taxes. And I'll go to the country with nothing.

The Senate is not governed in its debates by a rules committee, as is the House. One of the Senate's most cherished traditions is that of unlimited debate, which in 1964 could only be terminated a vote of two-thirds of the Senate: the cloture rule. Senators generally were reluctant to take any action that might make it easier to get cloture. So a southern filibuster against the civil rights bill was a virtual certainty, as the history of the 1957 and 1960 acts had shown. Only when civil rights advocates agreed to gut those bills had the southerners relented and allowed them to come to a vote.

Meanwhile, Johnson moved to cover his flank on the tax bill. In early January 1964 he invited Senator Harry Byrd, chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, to lunch to tell him he was trying to "stop the—and arrest the—spending and try to be as frugal as I can. . . . you are my inspiration for doing it." This was language that Byrd liked to hear; he wanted good news on the budget. Jack Valenti, sitting in on the lunch, described it:

The prime motive of that lunch was to get Byrd's agreement to release the tax cut from the committee, bring it to a vote so that it could go to the floor of the Senate. . . . He said to Harry: "This tax cut is vital to my program. I've got to have it." And Harry Byrd said, "Well, Mr. President, I don't see how we can get a tax cut as long as this budget is so big."

At that time the noise in the corridors was that the budget would be $107 billion to $109 billion. The President said to Harry Byrd, "Well now, Harry, suppose I could get this budget under $100 billion? I don't know that I can, but if I do, what do you think?" . . . . [A]nd Harry Byrd said, "We might be able to do some business." Then the President said, "Well, if I get this budget under $100 billion, Harry, do you think we can get this tax cut out of your committee and onto the floor?". . . . Harry Byrd said yes, he thought that if the budget came in under $100 billion, yes, he thought it was possible that the committee might act on it.

Immediately the President concluded that lunch. He had gotten a commitment out of Harry Byrd and he knew his man pretty well and knew that once Byrd gave his word he would not renege on it.

Even as he worked to get the tax bill out of the Senate Finance Committee, Johnson was devising strategy for the fight over the civil rights bill.

Johnson had arranged with Mike Mansfield, a Montana Democrat, his successor as Senate majority leader, to have Humphrey manage the civil rights bill. Humphrey's bona fides on civil rights were impeccable, and he was a good political tactician, although LBJ always mistrusted Humphrey for his loquacity and what Johnson considered a tendency to excessive liberalism.

Humphrey later recalled how LBJ worked on him when the President went into high gear on the 1964 bill. The President called him to the Oval Office, and in true Johnson fashion, issued a challenge:

"You have got this opportunity now, Hubert, but you liberals will never deliver. You don't know the rules of the Senate, and your liberals will all be off making speeches when they ought to be present in the Senate. . . . [Y]ou've got a great opportunity here, but I'm afraid it's going to fall between the boards." He sized me up; he knew very well that I would say, "Damn you, I'll show you. . . ." He knew what he was doing exactly, and I knew what he was doing. One thing I liked about Johnson: even when he conned me I knew what was happening. It was kind of enjoyable. I mean I knew what was going on, and he knew I knew.

The key to Senate passage of the civil rights bill was Minority Leader Dirksen, for only with substantial help from Senate Republicans was there any hope of success. Humphrey recalled LBJ putting it this way: "Now you know that bill can't pass unless you get Ev Dirksen. You and I are going to get Ev. . . . You make up your mind now that you've got to spend time with Ev Dirksen. You've got to play to Ev Dirksen. You've got to let him have a piece of the action. He's got to look good all the time."

So Humphrey spent considerable time conferring with Dirksen, in Dirksen's office. That infuriated Humphrey&'s liberal associates, who fumed, "You&'re the manager of the bill. We're the majority party. Why don't you call Dirksen to your office?" Humphrey replied, "I don't care where we meet Dirksen. We can meet him in a nightclub, in the bottom of a mine or in a manhole. It doesn't make any difference to me. I just want to meet Dirksen. I just want to get there."

Humphrey went public with that strategy. In early 1964 he made an appearance on Meet the Press. When asked how he expected to get civil rights passed, in light of Dirksen's early vocal opposition, Humphrey recalled replying, "Well, I think Senator Dirksen is a reasonable man. Those are his current opinions and they are strongly held, but I think that as the debate goes on he'll see that there is reason for what we're trying to do. . . . Senator Dirksen is not only a great senator, he is a great American, and he is going to see the necessity of this legislation."

Humphrey said later that LBJ immediately phoned him and exclaimed: "Boy, that was right. You're doing just right now. You just keep at that. . . . Don't you let those bomb throwers [LBJ's favorite synonym for liberals] now, talk you out of seeing Dirksen. You get in there and see Dirksen! You drink with Dirksen! You talk to Dirksen! You listen to Dirksen!"

On February 26 the Senate voted to place the bill on the Senate calendar rather than refer it to the Judiciary Committee, which was dominated by southerners. On March 26 the Senate agreed to begin debate on the floor.

Now the southerners began their expected filibuster. In past filibusters on civil rights, the southern senators, under the leadership of Richard Russell, a Georgia Democrat and a Johnson mentor, with superior discipline and organization, had worn down their opponents until they agreed to a compromise. This time things would be different, but the fight would be arduous and the outcome not foreordained.

Assistant Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach was the administration's point man in the coming struggle, and he advised beating the southerners at their own game. The pro–civil rights senators should simply out-organize and outlast the southerners until the necessary votes for cloture had been gathered. Humphrey agreed. Johnson was skeptical at first but allowed himself to be convinced.

Humphrey's Democratic forces prevented the filibustering southerners from using the parliamentary device of a quorum call, then resting their voices and their feet, while keeping the floor.

But all depended on getting the votes to impose cloture. If Russell and his southerners could delay action on civil rights through the summer and into the convention season, they hoped that their opposition might lose heart and accept compromise as they had in the past.

To get enough votes to impose cloture, Humphrey needed Dirksen's support, and some compromises were required. On May 13, Humphrey and Dirksen agreed on a key issue—the government would sue only in cases involving a "pattern or practice" of discrimination in public accommodations or fair employment. Not until June 10, however, was Mansfield able to call for a vote on cloture. The Senate then voted 71-29 to shut off further debate. On June 19 the Senate passed the civil rights bill, 73-27.

Still, there was the possibility that the House would insist on a conference committee of senators and representatives to iron out differences between the House and Senate versions of the bill.

After a bipartisan coalition took control of the House Rules Committee from Chairman Smith, the panel reported a resolution accepting the Senate version of the bill, ruling that only a single hour of debate on the bill would be allowed on the House floor.

On July 2, the House voted 289-126 to accept the Senate version of the bill. On the same day President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in the East Room of the White House.

The act elaborated on some voting rights issues in Titles I, VIII and XI, but the true successor to the civil rights measures of 1957 and 1960 was the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In the 1964 legislation, employment discrimination was addressed in Title VII, the only one in the 1964 act to include gender as a protected category, owing to Judge Smith's miscalculation.

The principal objects of attention and controversy in 1964 were the provisions mandating desegregation of public accommodations and facilities. Title II contained the prohibition against discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion or national origin in public accommodations such as restaurants, lodgings, and entertainment venues if their operation "affect[ed] commerce" or if such discrimination was "supported by State action" such as Jim Crow laws. Title III permitted the Justice Department, upon receipt of a "meritorious" complaint, to sue to desegregate public facilities, other than schools, owned or operated by state or local governments. Title IV permitted the attorney general to file suit to desegregate public schools or colleges under certain conditions, but it explicitly did not empower any federal official or court to require transportation of students to achieve racial balance.

The real hammer that broke segregated school systems, however, was Title VI, which barred discrimination in "any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance." Gary Orfield has written that fund cutoffs accomplished more by the end of the Johnson administration than had a decade of litigation following the Brown v. Board of Education decision, giving the Civil Rights Act "more impact on American education than any of the Federal education laws of the twentieth century." Beyond its effect against racial discrimination, the language in this title was the model for subsequent anti-discrimination legislation affecting gender, disabilities, and age. And Hugh Davis Graham has argued that Title VI, not Titles II or VII, which appeared to be the most important at the time, was actually the most significant because of its application in succeeding years to other institutions that had come to rely on federal money.

Finally, the impact of the 1964 act on the American political scene was profound. Bill Moyers, a former aide to LBJ, recalled, in a statement during a 1990 symposium at the Johnson Library:

The night that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, I found him in the bedroom, exceedingly depressed. The headline of the bulldog edition of the Washington Post said, "Johnson Signs Civil Rights Act." The airwaves were full of discussions about how unprecedented this was and historic, and yet he was depressed. I asked him why.

He said, "I think we've just delivered the South to the Republican Party for the rest of my life, and yours."

Ted Gittinger conducted oral history interviews for twelve years at the Lyndon B. Johnson Library and is now director of special projects there.

Allen Fisher has been an archivist at the Lyndon B. Johnson Library since 1991 and works primarily with domestic policy collections.

Note on Sources

The LBJ telephone tapes at the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library in Austin, Texas, are an invaluable resource. Through these, one hears the President directly, with no intermediaries.

Michael Beschloss's volumes on Johnson's telephone tapes provide interpretations of their context that would otherwise escape most readers: Taking Charge: The Johnson White House Tapes, 1963–1964, and Reaching for Glory: Lyndon Johnson's Secret White House Tapes, 1964–1965 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997, 2001).

The Miller Center of Public Affairs at the University of Virginia has published an excellent study on the 1964 Civil Rights Act in a volume in its Presidential Recordings Program: Jonathan Rosenberg and Zachary Karabell, Kennedy, Johnson, and the Quest for Justice: The Civil Rights Tapes (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2003). As the title suggests, the book is an overview of material from the surreptitious recordings those two Presidents made of meetings and telephone conversations during the struggle to pass a strong civil rights bill.

The recordings from the Johnson years are available for listening in the Reading Room at the LBJ Library and for purchase from the Archives. See the library's website for information about the collection and descriptions of the conversations released to date. The LBJ Museum Store carries a CD with twenty-six selected conversations from November 1963 to December 1965, and the Presidential Recordings Program's website has sound files in three formats.

The Jack Valenti and Bill Moyers quotations are from the proceedings of a 1990 symposium, The Johnson Years: The Difference He Made (Austin: The University of Texas Board of Regents, 1993). The quotations by Hubert Humphrey, George Reedy, A. Philip Randolph, Lawrence O'Brien, and Roy Wilkins are from their oral history interviews in the LBJ Library archives.

Julian E. Zelizer, Taxing America: Wilbur D. Mills, Congress, and the State (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998) is an excellent source for the connection between the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the tax issue.

Two narratives were particularly useful for background on the passage of the bill: Charles and Barbara Whalen, The Longest Debate (Cabin John, MD: Seven Locks Press, 1985), and Robert Mann, The Walls of Jericho: Lyndon Johnson, Hubert Humphrey, Richard Russell, and the Struggle for Civil Rights (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1996). For the significance of various parts of the act, see Legacies of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, edited by Bernard Grofman (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000).