The Ordeal of Herbert Hoover

Summer 2004, Vol. 36, No. 2

By Richard Norton Smith and Timothy Walch

Few Americans have known greater acclaim or more bitter criticism than Herbert Hoover.

The son of a Quaker blacksmith, Hoover was orphaned at the age of nine and sent to live with relatives in Oregon. Few expected the boy to amount to much, yet he defied those expectations and achieved international success as a mining engineer and worldwide gratitude as the "Great Humanitarian" who fed war-torn Europe during and after World War I. In the process, he developed a unique philosophy—one balancing responsibility for the welfare of others with an unshakable faith in free enterprise and dynamic individualism. In time this would lead him to feed more than a billion people in fifty-seven countries.

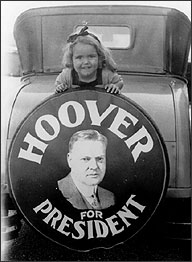

He was elected thirty-first President of the United States in a 1928 landslide, but within a few short months he had become a scapegoat in his own land. Even today, Herbert Hoover remains indelibly linked to an economic crisis that put millions of Americans out of work in the 1930s. His 1932 defeat left Hoover's once-bright reputation in shambles. But Herbert Hoover refused to fade away. In one of history's most remarkable comebacks, he returned to public service at the end of World War II to help avert global famine and to reorganize the executive branch of government.

By the time of his death in October 1964, Hoover had regained much of the luster once attached to his name. The Quaker theologian who eulogized him at his funeral did not exaggerate when he said of Hoover, "The story is a good one and a great one. . . . It is essentially triumphant."

Usually cast as a President defined by his failure to contain the Great Depression, Hoover's story is far more complex and more interesting. To begin with, Hoover was an activist reformer, albeit one without the political skills needed to sell himself and his programs to Congress and the public. A shy man, he insisted on keeping much of his life and good deeds out of the public eye. Only in politics is this a character flaw, yet it prevented those around Hoover from portraying him as a compassionate leader, or warding off portrayals of him as a cold, uncaring figure responsible for nearly everything that was going wrong in the American economy.

As a result, Hoover's presidency remains largely an untold story.

It began when Calvin Coolidge chose not to run for a second term in 1928. Hoover, then secretary of commerce (and joked Washington wags, "assistant secretary of everything else"), made no secret of his interest in succeeding Coolidge. Few men seemed so prepared for the nation's highest office. After all, he had fed Belgium, run the U.S. Food Administration for Woodrow Wilson, revolutionized the Department of Commerce, and ministered to victims of the Mississippi River flood. More realistic than Wilson, more respectable than Warren Harding, more imaginative than Calvin Coolidge, Hoover appeared an ideal candidate. Few Americans asked whether the Great Engineer had a political temperament.

It was an uphill campaign for Hoover's Democratic opponent. Governor Alfred E. Smith was a colorful, charismatic product of New York's lower East Side and an urban hero to many. But as the first Catholic to be nominated for President, Smith was targeted by nativist elements.

In fact, the 1928 election was a contest between two self-made men, each of whom celebrated the glories of American individualism. Confronted with a heroic opponent who took credit for prosperity while vowing to eliminate society's imperfections, some of Smith's partisans tried portraying Hoover as a dangerous radical. Franklin D. Roosevelt said of Hoover, "He has shown in his own department an alarming desire to issue regulations and to tell businessmen generally how to conduct their affairs."

One of the few major issues dividing the candidates was Prohibition, with Hoover supporting the constitutional ban on manufacturing and selling alcoholic beverages and Smith pressing for its repeal. In November voters overwhelmingly endorsed the Republican ticket, giving Hoover 58 percent of the popular vote and 444 electoral votes to Smith's 87.

Hoover's sense of triumph was muted. "My friends have made the American people think of me a sort of superman," he told the Christian Science Monitor shortly before he was inaugurated: "They expect the impossible of me and should there arise in the land conditions with which the political machinery is unable to cope I will be the one to suffer." It was an uncanny prophecy. On March 4, 1929, inauguration day, Hoover's address celebrated prosperity while insisting that more could be done to spread its benefits evenly. Unveiling his own version of "kinder, gentler" capitalism, he declared, "We want to see a nation built of homeowners and farm owners. We want to see more and more of them insured against death and accident, unemployment and old age. We want them all secure."

True to his instincts, Hoover's first months in office were a whirlwind of reform. Within thirty days of his inauguration, the new President announced an expansion of civil service protection throughout the federal establishment, canceled private oil leases on government lands, and directed federal law enforcement officials to focus their energies on gangster-ridden Chicago, leading to the arrest and conviction of Al Capone on tax evasion charges.

A Hoover-appointed commission paved the way for an additional 3 million acres of national parks and 2.3 million acres in national forests. In the summer of 1929 the President convinced a special session of Congress to establish a Federal Farm Board to support farm prices. He pressed ahead with plans for a series of dams in the Tennessee Valley and in central California and tax cuts graduated to favor low-income Americans. In other domestic initiatives, Hoover created the Veterans Administration and doubled the number of veterans' hospital facilities, established the antitrust division of the Justice Department to prosecute unfair competition and restraint of trade cases, required air mail carriers to improve service, and advocated federal loans for urban slum clearance.

Hoover also established the Federal Bureau of Prisons and reorganized the Bureau of Indian Affairs to protect Native Americans from exploitation. He proposed a federal Department of Education as well as fifty-dollar-a-month pensions for Americans over sixty-five—the last proposal falling by the wayside after Wall Street crashed. In November 1930, Hoover presided over pioneering White House conferences on child health and protection and home building and home ownership.

Hoover was similarly activist in his foreign policies. Determined to halt the arms race, he imposed an arms embargo to Latin America, proposed a one-third cut in the world's armadas of submarines and battleships, and sought unsuccessfully to eliminate all bombers, tanks, and chemical warfare. The administration negotiated a treaty authorizing construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway along the U.S.-Canadian border, only to have it fall victim to senatorial opposition.

Hoover was not shy about sharing his concerns about the American economy. As early as 1925, then-Secretary of Commerce Hoover had warned President Coolidge that stock market speculation was getting out of hand. Yet in his final State of the Union Address, Coolidge saw no reason for alarm. Hoover, however, remained fearful. Even before his inauguration, he urged the Federal Reserve to halt "crazy and dangerous" gambling on Wall Street by increasing the discount rate the Federal Reserve charged banks for speculative loans. He asked magazines and newspapers to run stories warning of the dangers of rampant speculation.

But Presidents in 1929 were not supposed to regulate Wall Street, or even talk about the gyrating market for fear of inadvertently setting off a panic, and Hoover backed off. He also had a personal reason for keeping quiet. His conscience was pained after a friend took his advice to buy a stock that later nose-dived. "To clear myself," the President told friends, "I just bought it back and I have never advised anybody since."

By September 1929 the market topped out, some eighty-two points above its January plateau. The last week of October, however, brought a terrible reckoning. On October 24 alone, radio stocks lost 40 percent of their paper value. On Black Tuesday, the twenty-ninth, the market collapsed. In a single day, sixteen million shares were traded—a record—and thirty billion dollars vanished into thin air.

Refusing to accept the "natural" economic cycle in which a market crash was followed by cuts in business investment, production, and wages, Hoover summoned industrialists to the White House on November 21, part of a round-robin of conferences with business, labor, and farm leaders, and secured a promise to hold the line on wages. Henry Ford even agreed to increase workers' daily pay from six to seven dollars. From the nation's utilities, Hoover won commitments of $1.8 billion in new construction and repairs for 1930. Railroad executives made a similar pledge. Organized labor agreed to withdraw its latest wage demands.

The President ordered federal departments to speed up construction projects. He contacted all forty-eight state governors to make a similar appeal for expanded public works. He went to Congress with a $160 million tax cut, coupled with a doubling of resources for public buildings and dams, highways, and harbors. Looking back at the year, the New York Times judged Commander Richard Byrd's expedition to the South Pole—not the Wall Street crash—the biggest news story of 1929. Praise for the President's action was widespread. "No one in his place could have done more," concluded the Times in the spring of 1930, by which time the Little Bull Market had restored a measure of confidence on Wall Street. "Very few of his predecessors could have done as much."

Economists are still divided about what caused the Great Depression and what turned a relatively mild downturn into a decade-long nightmare. Hoover himself emphasized the dislocations brought on by World War I, the rickety structure of American banking, excessive stock speculation, and Congress's refusal to act on many of his proposals. The President's critics argued that in approving the Smoot-Hawley tariff in the spring of 1930, he unintentionally raised barriers around U.S. products, worsened the plight of debtor nations, and set off a round of retaliatory measures that crippled global trade.

Neither claim went far enough. In truth, Hoover's celebration of technology failed to anticipate the end of a postwar building boom, or a glut of twenty-six million new cars and other consumer goods flooding the market. Agriculture, mired in depression for much of the 1920s, was deprived of cash it needed to take part in the consumer revolution. At the same time, the average worker's wages of $1,500 a year failed to keep pace with the spectacular gains in productivity achieved since 1920. By 1929 production was outstripping demand.

The United States had too many banks, and too many of them played the stock market with depositors' funds or speculated in their own stocks. Government had yet to devise insurance for the jobless or income maintenance for the destitute. With unemployment, buying power vanished overnight. Together, government and business actually spent more in the first half of 1930 than in all of 1929. Yet such bold action did little to help the economy as frightened consumers cut back their expenditures by 10 percent and a severe drought ravaged the agricultural heartland beginning in the summer of 1930. Foreign banks went under, draining U.S. wealth and destroying world trade. Unemployment soared from five million in 1930 to more than eleven million in 1931. A sharp recession had become the Great Depression.

No American President entered office with greater expectations, or left with more bitter disappointments, than Herbert Hoover. "I only wish I could say what is in my heart," he remarked as hard times engulfed the nation and his popularity evaporated. Herbert Hoover's heart never could subdue his head.

In between nibbles at Camp Rapidan, the fishing camp in Virginia's Blue Ridge Mountains he built with $120,000 of his own money, the embattled President held front-porch conferences with congressmen and economic advisers. "I have discovered that even the work of the government can be improved by leisurely discussions out under the trees," said Hoover. All that work took its toll. After the White House physician urged Hoover to lose weight, he adapted a game of medicine ball he had first played during a Latin American journey. For thirty minutes each day, seven days a week, Hoover and his "Medicine Ball Cabinet" heaved a six-pound medicine ball back and forth over a volleyball net. It was a game that burned up three times as many calories as tennis and six times that of golf.

But this sports-loving President couldn't relax in public. For example, he stopped one afternoon to watch a sandlot ball game, cheering on the kids at play and informally chatting with them after the game ended. Colleagues urged the President to return the next day and be photographed with the boys, saying it would be good for his public image. Hoover would do nothing of the kind! It was one thing to relax, however infrequently, quite another to perform. "You can't make a Teddy Roosevelt out of me!" he proclaimed, to the despair of advisers.

Generous to a fault, Hoover was one of two American Presidents to give away his salary (John F. Kennedy was the other). He anonymously donated $25,000 a year to aid victims of the Depression and raised $500,000 toward the 1930 White House Conference on Child Health and Welfare. True to form, the President kept his own family shielded from view. Young Allan Hoover, a student at Stanford University, appeared infrequently at the White House. And when Herbert Junior was confined to a North Carolina treatment center for tuberculosis, his father could only spare time for a single visit. During this period the President's daughter-in-law, Margaret, and her children, Peggy Ann and Herbert III (known as Pete) lived at the White House. The 1930s equivalent of spin doctors wanted the youngsters brought into the spotlight, if only to soften their grandfather's somewhat down image, but Hoover flatly refused to exploit his family.

Hoover's presidency showed the limitations of managerial government in a time of national emergency. With his stiff-necked refusal to play the political game, the President clung to the same theories of individual initiative and grassroots cooperation that had fed and salved war-torn Europe and ministered to flood victims in this country. "A voluntary deed is infinitely more precious to our national ideal and spirit than a thousand-fold poured from the Treasury," he said. Here was the practical idealism that had raised Hoover to the presidency, only to become a ball and chain hobbling him from galvanizing a nation in extremis.

To most Americans, the President was a remote, grim-faced man in a blue, double-breasted suit. They saw none of his private anguish throughout sixteen-hour days, engaging in fruitless mealtime conferences with economists, politicians, and bankers. Hoover's hands shook as he lit one cigar after another. His hair turned white, and he lost twenty-five pounds. Holding office at such a time, said Hoover, was akin to being a repairman behind a dike. "No sooner is one leak plugged up than it is necessary to dash over and stop another that has broken out. There is no end to it."

Defensive to the point of bewilderment, he told reporters, "No one is actually starving." In fact, said Hoover, he knew of one hobo who had managed to beg ten meals in a single day. He once offered Rudy Vallee a gold medal if the popular entertainer could come up with a joke to curtail hoarding of gold. Increasingly the joke, such as it was, was the man U.S. News called "President Reject." "Mellon pulled the whistle," went one Democratic campaign doggerel, "Hoover rang the bell, Wall Street gave the signal, And the country went to hell."

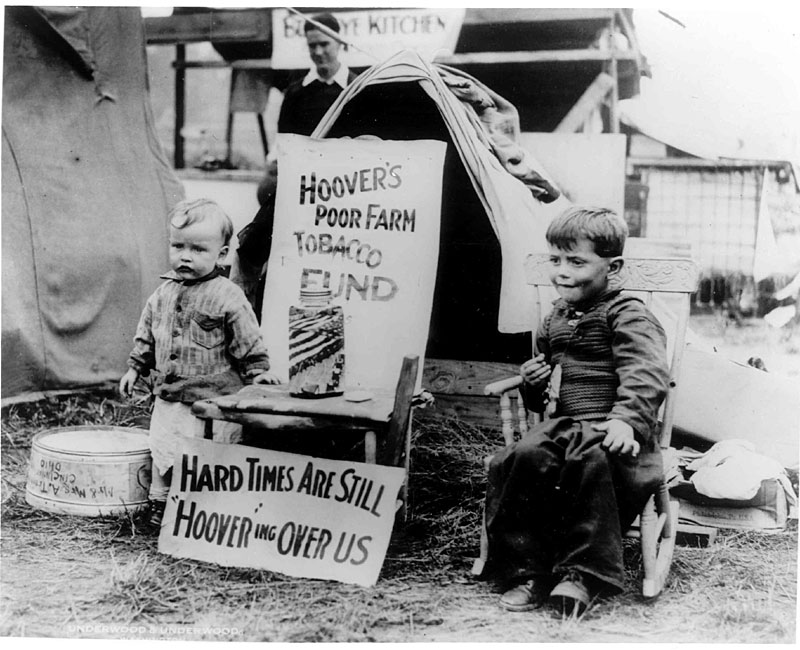

Will Rogers summed up the mood of a nation: If someone bit an apple and found a worm in it, he joked, Hoover would get the blame. Desperate encampments of tin and cardboard shacks were dubbed "Hoovervilles." There were "Hoover hogs" (armadillos fit for eating), "Hoover flags" (empty pockets turned inside out), "Hoover blankets" (newspapers barely covering the destitute forced to sleep outdoors), and "Hoover Pullmans" (empty boxcars used by an army of vagabonds escaping from their roots).

Hoover adopted a bloody but unbowed stance. "I cannot take the time from my job to answer such stuff," he said. At the same time it must be said that he did little to advance his cause. Building speeches like an engineer builds a bridge, Hoover delivered his statistic-laden texts in a dish-watery monotone. His face wore the look of a condemned man, not a confident leader.

He shied away as if by instinct from the emotional aspects of modern, mass leadership. In the spring of 1932, three Detroit children hitchhiked to Washington to try to get their father out of jail. Hoover was deeply moved and ordered the father released immediately. Yet he refused to let the press be informed or the children exploited for his personal political advantage. From hero to scapegoat: Hoover's failure to dramatize himself was his greatest strength as a humanitarian and his greatest flaw as a politician.

Hoover indulged in a rare bit of whimsy during a 1931 meeting with former President Coolidge. After his successor had outlined a host of anti-Depression measures, Coolidge offered wry consolation. "You can't expect to see calves running in the field the day after you put the bull to the cows," he commented. "No," replied Hoover, "but I do expect to see contented cows."

There was precious little contentment among Hoover's countrymen. One day in 1931, ten thousand Communist demonstrators picketed the White House with placards reading, "The Hoover program—a crust of bread and a bayonet." Congress, for whom the next election seemed more important than unity in the midst of crisis, stubbornly resisted the President. "Why is it that when a man is on this job as I am," raged a baffled Hoover, "day and night, doing the best he can, that certain men . . . seek to oppose everything he does, just to oppose him?"

In the summer of 1932, in the midst of the Great Depression, World War I veterans seeking early payment of a bonus scheduled for 1945 assembled in Washington to pressure Congress and the White House. Hoover resisted the demand for an early bonus. Veterans' benefits already took up 25 percent of the 1932 federal budget. Even so, as the Bonus Expeditionary Force swelled to sixty thousand men, the President secretly ordered that its members be given tents, cots, army rations, and medical care.

In July, the Senate rejected the bonus 62 to 18. Most of the protesters went home, aided by Hoover's offer of free passage on the rails. Ten thousand remained behind, among them a hard core of Communists and other militants. On the morning of July 28, forty protesters tried to reclaim an evacuated building in downtown Washington scheduled for demolition. Fighting back, police killed two marchers. Local officials sought help. Hoover reluctantly sent in federal troops, but only after limiting Maj. Gen. Douglas MacArthur's authority. MacArthur's troops would be unarmed. Their mission was to escort the marchers to camps along the Anacostia River.

In the event, MacArthur ignored the President's orders. Taking no prisoners, the flamboyant general drove tattered protesters from their encampment. After Hoover ordered a halt to the army's march, MacArthur again took things into his own hands, violently clearing the Anacostia campsite. A national uproar ensued. In far-off Albany, New York, Democratic presidential candidate Roosevelt grasped the political implications instantly. "Well," he told a friend on hearing the news, "this elects me."

At first, Hoover himself appeared to agree with Roosevelt. Intending to make only three speeches on his behalf, as the contest heated up, the President took to the campaign trail for weeks on end. He had no illusions. "We are opposed by six million unemployed, 10,000 bonus marchers, and 10 cent corn," he remarked, "Is it any wonder that the prospects are dark?"

His arguments did little to dispel the doubts of listeners. "Let no man tell you it could not be worse," he told one audience. "It could be so much worse that these days now, distressing as they are, would look like veritable prosperity." This was hardly an inspiring message, especially at a time when the magical Roosevelt was appealing to the "forgotten man." Everywhere Hoover went he saw evidence of the nation's bitterness. He was jeered outside a Detroit arena and hooted at in Oakland. After tomatoes were thrown at his train in Kansas, he said dejectedly, "I can't go on with it anymore." But he did, warning of the threat to individual freedom posed by Roosevelt's vaguely defined New Deal.

Election Day was a Democratic sweep, as Roosevelt carried all but six states. Hoover received the bad news at his California home. A few days later, on the eastbound presidential train to Washington, a friendly journalist encountered an exhausted chief executive. The President looked up at his visitor with a one-word greeting. "Why?" he asked.

And it was far from over. In the last weeks of his term, Hoover faced a desperate crisis of confidence as uncertain investors—or so he thought—sought reassurance that the new Roosevelt administration would defend the gold standard. On February 17, 1933, the President wrote the President-elect, seeking guarantees that Roosevelt would balance the budget, combat inflation, and halt publication of loans made by the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. Roosevelt, sensing that his discredited predecessor was trying to tie his hands, kept silent.

Soon banks in two dozen states began to totter. Hoover denounced corrupt bankers as worse than Al Capone ("He apparently was kind to the poor"). In his desperation he proposed that the Federal Reserve guarantee every depositor's account, an idea that would eventually become law. But in February 1933 the Federal Reserve's governors preferred a general bank holiday instead. Hoover refused to take such a drastic action without Roosevelt's agreement. And FDR had his own agenda.

Twice on the night of March 3, Hoover telephoned the President-elect trying to persuade him to join in concerted action. FDR replied that governors were free to do what they wished on a state-by-state basis. A little after one in the morning, the governors of New York and Illinois unilaterally suspended banking operations in their states. "We are at the end of our string," a bone-weary President remarked to his secretary that morning, "there is nothing more we can do."

"Democracy is a harsh employer," said Herbert Hoover in recalling his 1932 defeat. Rejected by his countrymen, Hoover departed Washington in March 1933, his once bright reputation in shambles and his career in public service apparently at an end. The Roosevelt era was, for Hoover, his own purgatory, during which the former President was forced to defend himself against charges that he had somehow caused the Great Depression or done little to combat it.

Even in these wilderness years, however, Hoover's voice was not silenced. He wrote book after book, delivered countless speeches, twice reorganized the executive branch of the government, and raised tens of millions of dollars for favorite causes, such as his beloved Stanford University, where he was a member of the first graduating class in 1895. In 1941, he dedicated the towering headquarters of the Hoover Institution at Stanford, destined to become one of the world's foremost scholarly centers and a major recruiting ground for conservative Presidents and their administrations.

In October 1936 the former President found a new cause, one that would engage him for the rest of his life. The same night Hoover joined the board of the Boys' Clubs of America, he was elected its chairman. For Hoover this was only the latest, most logical chapter in the story of an Iowa orphan who had fed millions of children before he organized the American Child Health Association.

"The boy is our most precious possession," Hoover said in the spring of 1937. Unfortunately, he said, "we have increased the number of boys per acre." For the youthful resident of urban America, that meant a life "of stairs, light switches, alleys, fire escapes . . . and a chance to get run over by a truck," he added. A boy denied the pleasures of nature had to contend with the policeman on the beat. But packs need not run into gangs, said Hoover, not so long as "pavement boys" had a place to play checkers and learn a trade, swim in a pool and steal nothing more harmful than second base. Hoover determined to start a hundred new Boys Clubs in three years. He more than met his goal. Not long before his death, he was embarking on a still more ambitious plan—"A Thousand Clubs For A Million Boys."

In May 1945 Harry Truman invited America's only living former President to visit him at the White House. "I would be most happy to talk over the European food situation with you," wrote Truman. "Also it would be a pleasure for me to become acquainted with you." It was the start of an improbable, yet historic friendship between two men who formed perhaps the oddest couple in American politics. Early in 1946 Truman dispatched the seventy-one-year-old Hoover to thirty-eight nations in an effort to beg, borrow, and cajole enough food to avert mass starvation among victims of World War II. Back home Hoover appealed to his countrymen to reduce consumption of wheat and fats, saying, "We do not want the American flag flying over nationwide Buchenwalds."

Thanks to Truman, Hoover was again doing what he did best, feeding people. His relationship with Truman deepened, despite political differences. Truman restored Hoover's name to the great dam that Roosevelt's administration had called Boulder Dam. In 1947 he asked the Great Engineer to reorganize an executive branch of government bloated by war, to make it more efficient if not necessarily more conservative. It was a daunting task: not only did Uncle Sam defend the nation and shape basic economic policy—he also manufactured ice cream, helium, and retreaded tires; operated a railroad in Panama and a distillery in the Virgin Islands; and owned one-quarter of the continental United States and twenty-seven billion dollars in personal property.

Unfortunately no one could account for more than a fraction of the whole. Do more with less: that was the theme of the Hoover commission's reports, each written by its chairman to fit on a single page of the New York Times. Not all his ideas were approved, but Truman, reelected against all odds in 1948, supported enough to see more than 70 percent of Hoover's recommendations become law. All this purposeful activity had added ten years to his life, a grateful Hoover told friends. Writing to Truman in 1962, he remarked, "Yours has been a friendship which has reached deeper into my life than you know."

In 1953 a second Hoover Commission returned to the task of pruning big government. This time its chairman lamented that he got less support from President Dwight D. Eisenhower than from Truman. Even so, as late as 1961, John F. Kennedy's secretary of defense, Robert McNamara, was thanking Hoover for ideas that could save billions in Pentagon spending.

Over time, Hoover took a detached, even whimsical view of the shifting currents of opinion. Asked how he had survived the long years of ostracism coinciding with Roosevelt's New Deal, he said simply, "I outlived the bastards." With a twinkle in his eye, he proposed a set of reforms in American life, including four strikes in baseball "so as to get more men on bases . . . the crowd only gets worked up when somebody is on second base," an end to political ghostwriters, and the scheduling of all after-dinner speakers before dinner "so that the gnaw of hunger would speed up terminals."

The former President became a kind of national Dutch uncle, advising Presidents of both parties. A reporter who dropped by the Waldorf Towers in New York City, where he lived, in 1960 could hardly believe that Hoover worked eight to twelve hours each day. After all, said the journalist, the former President was nearly eighty-six years old. "Yes," replied one of his secretaries, "but he doesn't know that." With his unending series of books, articles, speeches, and other public appearances, Hoover reinvented the ex-presidency. Long before his death, at age ninety, in October, 1964, he had regained much of his countrymen's esteem.

Today he lies beneath a slab of Vermont marble within sight of the tiny fourteen-by-twenty-foot white frame cottage in West Branch, Iowa, where his life began. In a final demonstration of Quaker simplicity, his tombstone carries no presidential seal, no inscription of any kind, simply the name Herbert Hoover and the dates 1874–1964. It is a deliberately understated comment on a highly dramatic life.

Richard Norton Smith is the former director of the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library-Museum. He also served as director of the Eisenhower, Reagan, and Ford presidential libraries and most recently he was executive director of the Robert J. Dole Institute of Politics. He is currently the executive director of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library-Museum. A prolific writer, Smith is the author of An Uncommon Man: The Triumph of Herbert Hoover (1984) and is at work on a biography of Nelson Rockefeller.

Timothy Walch is the current director of the Hoover Presidential Library-Museum. Prior to coming to West Branch, he served as editor of Prologue. Walch is the author or editor of many books including (with Richard Norton Smith) Farewell to the Chief: The Role of Former Presidents in American Public Life (1990) and At the President's Side: The Vice Presidency in the Twentieth Century (1997). Most recently he published Uncommon Americans: The Lives and Legacies of Herbert and Lou Henry Hoover (2003).

Note on Sources

This essay is based on many years of research in the holdings of the Hoover Library. For additional biographical information on Herbert Hoover, see Richard Norton Smith, An Uncommon Man: The Triumph of Herbert Hoover (1984) and Timothy Walch, editor, Uncommon Americans: The Lives and Legacies of Herbert and Lou Henry Hoover (2003)