A Gold Mine of Naturalization Records in New England

Fall 2004, Vol. 36, No. 3 | Genealogy Notes

By Walter V. Hickey

The search for nineteenth-century naturalization records can be one of the more frustrating aspects of genealogical research. Before September 27, 1906, naturalization was carried out by thousands of courts—federal, state, county, local—and each court kept its own records. Where does one begin to look?

Researchers tracking down people who were naturalized in New England have an advantage, though. The National Archives–Northeast Region (Boston) has a unique set of records that brings together naturalization documents created in various New England courts. These records consist of photostatic copies, called "dexigraphs," made in the 1930s, of naturalization proceedings in all courts—federal, state, county, and local—in five of the New England states (Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont) between 1790 and September 26, 1906.

As a general rule, records in the National Archives have been created by federal agencies, and they are original records, not copies. How did copies of nonfederal records end up in the National Archives? Why are there copies? Therein lies a wonderful tale of serendipity.

Gathering Court Records to Document U.S. Citizenship

During the Great Depression, many employment and relief opportunities were limited to citizens of the United States. Anyone looking for work from the Work Projects Administration (WPA), for example, was required to prove U.S. citizenship, and civil service, old-age pensions, the right to vote, and other benefits and privileges were reserved for citizens. Additionally, many positions in private employment were open to Americans alone.

This requirement posed a problem for those who had become U.S. citizens as wives or children of a naturalized citizen. Most courts, if indeed not all, recorded only the name of the person being naturalized—the head of household. Although the wife and children of foreign birth under twenty-one years old derived their own citizenship from the husband or father, their names were not mentioned at all in the final official record. How could they prove their citizenship?

To assist those who needed to document citizenship, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) used a WPA project to photograph "something" of the fact of naturalization in all of the courts. Under this project, various courts in Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont made their naturalization records available to the INS. Clerical staff then summarized critical data on index cards to create an index, and WPA workers copied the naturalization records using the dexigraph reproduction system. The WPA started with New England, New York, and Illinois, but World War II halted the project before it could get to courts in other regions.

From the late 1930s until about 1961, the INS used these copies to document citizenship granted before 1907, whether it was of the actual petitioner or of the wife or child who derived citizenship. If the INS found a record, it then sent a form to the court holding the originals asking for verification of the data.

Two examples, taken from a 1940 report on the copying project, illustrate how the INS used the dexigraphs.

The Case of Miss Y

Miss Y was one year old when she arrived in Boston with her parents in 1865. She never married but always supported herself, earning a small salary. When she became too old to work and her savings dwindled, she was in danger of losing her home. Miss Y was advised to apply for old-age assistance, but she had no proof of citizenship. She remembered, however, that when she was seven years old, her father had said to her: "Well, we are both good Americans now." Thirteen courts had naturalization jurisdiction in Boston in the 1870s, but because Miss Y could not remember where her family had lived then, it was impossible to know where to start a search. The dexigraph photostats of records from those courts came to the rescue. The INS staff found Miss Y's father's name in the index, then retrieved the record. With this proof of derivative citizenship, Miss Y secured old-age assistance.

The Case of Mister X

Mr. X, naturalized in 1830, lived in the United States for ten years, then moved to Canada. One of his Canadian-born sons came to the United States to attend college, then returned to Canada, where he married and had a son. That grandson of Mr. X later went to the United States to work, but the promised job required proof of American citizenship. Through the dexigraph copies of naturalization records, he was able to show that his grandfather had become a U.S. citizen in 1830. Because his own father was a United States citizen through Mr. X and had resided in the United States, the grandson could claim American citizenship also.

How the Records Came to the National Archives

By 1961, the INS had no further use for these records. Because they were copies, they were eligible for destruction, and the INS authorized the federal records center in Boston to destroy the dexigraphs. The chief of the center's accession and disposal branch later wrote in a memo, "In accordance with the usual procedure, arrangements were made for the 'witnessed' destruction of these records; and they were loaded on a truck and taken to a pulping mill near Haverhill, Massachusetts. When the truck reached the mill it appears . . . that some boxes may have actually entered the pulping machine. At this point employees of the pulping mill determined that the paper used in the dexigraphs could not be used by the mill, and they refused to accept the remainder of the shipment."

The remaining boxes were returned to the records center. Now the question was what to do with them? Perhaps the National Archives would like the records? The regional director of the Boston records center wrote to the Office of Records Management in Washington, D.C., on July 25, 1961: "We realize these are duplicates of the court records and as such are disposable as non-record materials, but inasmuch as the original court records (especially state courts) are not so readily available for research, we thought the existence of these copies in one collection should be brought to the attention of the National Archives before we destroy any of them."

The reply from Washington was favorable. An appraisal archivist reported, "Before 1906 no centralized record of naturalizations was kept. Since naturalization proceedings could occur not only in federal courts, but also in state and local courts, the locating of a naturalization record is very difficult. This collection of copies of naturalization records for most of the New England area, and covering so large a span of years, has unique value. I do not believe there need be any question of their being, as a collection, Federal records."

A concurring report from the records management office declared that "any consolidation of records regarding naturalizations before September 27, 1906, will be helpful to genealogists and will furnish a wealth of materials for the sociologist and the historian. The dexigraphs have value as security copies of court records often scattered and inaccessible. Some original records may even have been lost or burned since these copies were made."

By January 1964, the records had been transferred to the National Archives in Washington, D.C., as part of Record Group 85, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, where they remained until their transfer in the 1980s to NARA's regional archives in Waltham, Massachusetts, near Boston.

At Waltham these records constitute the most heavily used collection of records, both by on-site researchers and those requesting copies through the mail, e-mail, or telephone. Even though these are copies, they are accessioned records and are handled as though they were originals.

Using the Dexigraphs

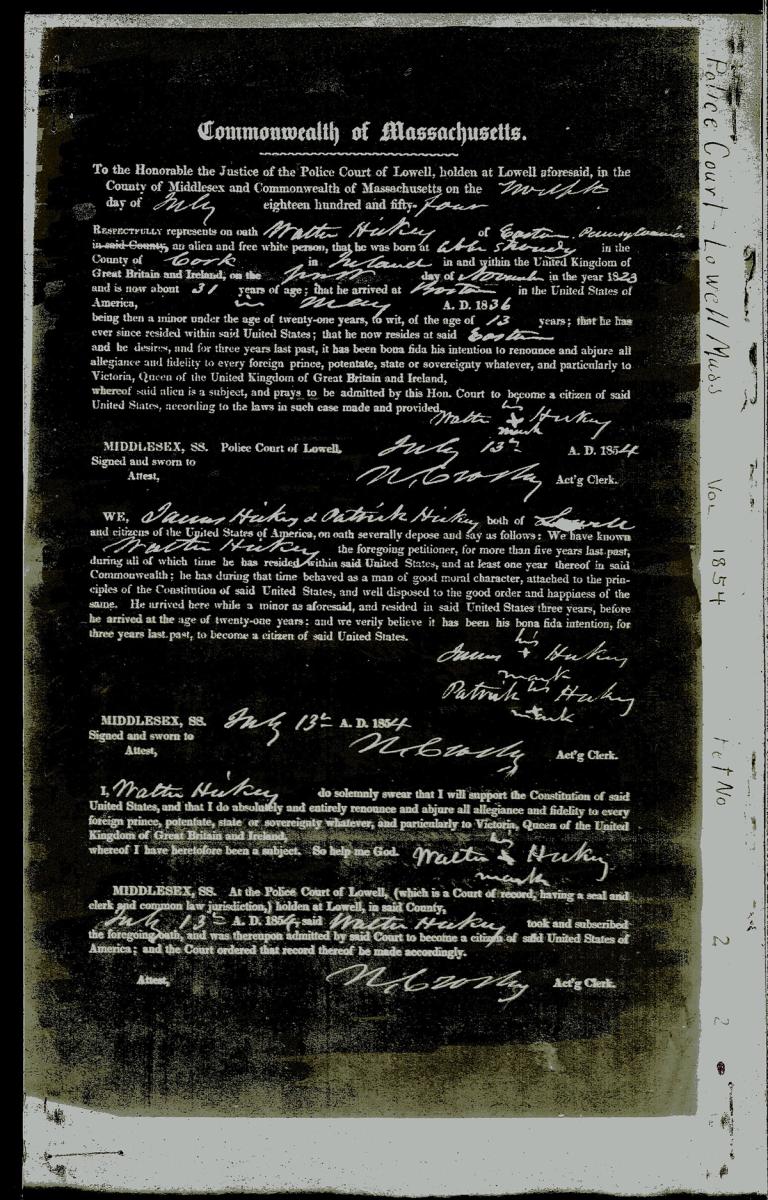

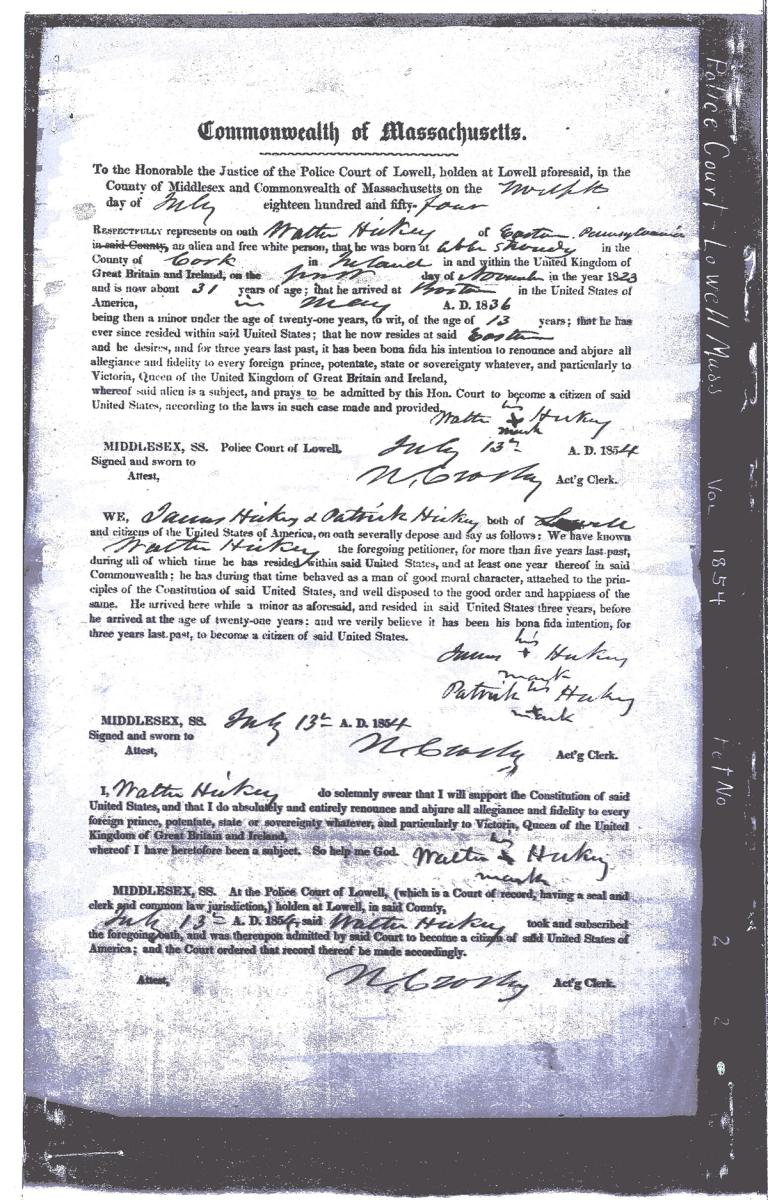

This collection consists of 5-by-8-inch negative photostats of the records of 301 courts. Nine of these courts are the federal circuit and district courts in the five states; 292 are state and local courts. It is not an exaggeration to say that these 301 courts used almost 300 forms and 300 filing systems. But these records all have one thing in common. They serve as documentation that an individual was admitted to United States citizenship. The greatest challenge to researchers lies in the content of each record.

Before September 27, 1906, each court asked whatever questions it felt appropriate on the form it chose and filed the records—or destroyed them—in the manner it felt appropriate. From a genealogical viewpoint, a "good" record may provide something about the date and place of birth and the date and port of arrival in the United States. Additionally, a record may contain the names and sometimes the addresses of the two witnesses. This information can provide further leads because a witness was required to be a citizen. Even in the absence of any personal information, a record may indicate that the petitioner was an honorably discharged veteran of the Civil War. Some courts might have required none of this information. Naturalization records will not provide parents' names, nor will they provide the names of the wife and children of the petitioner.

The dexigraphs indicate that a person had been naturalized or at least had filed a petition. Some petitions were denied for various reasons; others lapsed because the applicant never followed through. Other individuals did become citizens but later renounced their citizenship or otherwise had it taken away. For these reasons, the INS used the dexigraph as an indicator of citizenship and then checked with the court retaining the original record.

In the dexigraph collection, the declarations of intention filed with the petitions were not filmed for most courts. If a declaration was filed, the researcher should contact the original court to determine the existence of those papers. The declaration may or may not contain additional information.

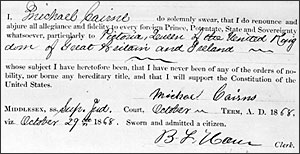

Michael Cairns did not have to file a declaration because he was a Civil War veteran. On some individuals' naturalization petitions, the words "being then a minor under the age of eighteen years" are struck out. This means the applicant was over eighteen when he arrived, and there should be a declaration of intention giving the name of the court and a date of filing. If one arrived before his eighteenth birthday, a declaration would not have been required. In some courts the cut-off age is given as twenty-one.

Obtaining Copies of the Records

NARA's Waltham staff will search the index and provide copies for a fee if the following information is provided: the name of the applicant; town of residence when applying; and an approximate date of birth. An approximation of the year of birth may be learned from census records. Indications of naturalization may be found in the census schedules of 1870 and 1900–1930. Names of spouses and children are not required as they will not be mentioned in any of the records.

The index to these dexigraphs has been microfilmed as NARA Microfilm Publication M1299, Index to New England Naturalization Petitions, 1791–1906. This publication is available at the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C., and some regional archives as well as through the Family History Centers of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

If a person is not found in the index, check other sources, such as the voter registration office in the community where the person resided, to discover the name of the court where he was naturalized. Because this WPA indexing project was quite large, individuals were bound to be left out. Sometimes a record will not be found even though a census schedule indicates a person was naturalized. Some individuals are recorded on the census as being naturalized ("NA") when in fact they might only have filed first papers. A person who filed only a declaration of intention and never followed through with a petition will not be found in the index. The index is to petitions only.

The dexigraphs of New England naturalizations may be an untraditional collection of records for NARA, but it has proved itself to be an extremely valuable resource for genealogists, providing them with a kind of "one-stop shopping" for naturalization records for Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont up to 1906. Thanks to serendipity and some forward-thinking NARA archivists, this important collection still exists today for the use of all.

Walter V. Hickey is an archives specialist in the National Archives and Records Administration–Northeast Region (Boston) and has previously worked in the Pittsfield branch of the Northeast Region. He is a frequent lecturer to genealogical organizations throughout New England.

Note on Sources

Background on the WPA project to copy and index the New England court records, as well as the stories of Miss Y and Mr. X were found in "The Story of Our Project" (May 1940), by the project's supervisor, Helen L. Watson. This report is part of a series entitled Records of the Massachusetts Open House Week, 1940, in the Records of the Work Projects Administration (Record Group 69).

Evans Walker, chief of the Accession and Disposal Branch at the Boston Federal Records Center, wrote to Kenneth Munden, director of Archival Projects Division, Washington, DC, on January 27, 1964, about the disposal and rescue of the dexigraph copies. According to Walker, it appears likely that the boxes that were pulped contained the dexigraphs of records of the United States Circuit Court for Massachusetts as volumes of dexigraphs from that collection are missing. Fortunately, NARA's Northeast Region (Boston) holds the original records.

The contemporary reports regarding the disposition of the naturalization records are from memorandums prepared by the Boston regional director Alan E. Gorham to the director of the Records Center Division, Office of Records Management, Washington, D.C. (July 25, 1961) and appraisal archivist Bess Glenn to G. Philip Bauer, acting chief archivist of the General Records Division (July 28, 1961).

Although the illustrations are of Massachusetts records, similar ones exist for the other New England states.

The indexes to dexigraph records for New York City and Illinois have also been microfilmed:

M1285, Soundex Index to Naturalization Petitions for the United States District and Circuit Courts, Northern District of Illinois, and Immigration and Naturalization Service District 9, 1840–1950. 179 rolls.

M1674, Index (Soundex) to Naturalization Petitions Filed in Federal, State, and Local Courts in New York, New York, Including New York, Kings, Queens, and Richmond Counties, 1792–1906. 294 rolls.