“Jitterbugs” and “Crack-pots”

Letters to the FCC about the “War of the Worlds” Broadcast

Fall 2003, Vol. 35, No. 3

By Lee Ann Potter

"Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. From the Meridian Room in the Park Plaza in New York City, we bring you the music of Ramon Raquello and his orchestra."

The sounds of "La Cumparsita" began to fill the airwaves. But within moments, the performance was interrupted by a special bulletin from the Intercontinental Radio News, telling of strange explosions of incandescent gas occurring at regular intervals on the planet Mars.

This dramatic approach—a performance interrupted by periodic news bulletins—is how writer Howard Koch adapted H. G. Wells's classic novel The War of the Worlds for radio broadcast. On October 30, 1938, the actors of The Mercury Theatre on the Air, led by twenty-three-year old Orson Welles, presented the adaptation on the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS). Within the first forty minutes of the program, the actors had vividly described Martians landing in New Jersey and decimating the state.

It was Halloween Eve. As Welles explained at the end of the broadcast, the adaptation of The War of the Worlds was a holiday offering—"The Mercury Theatre's own radio version of dressing up in a sheet and jumping out of a bush and saying Boo!" But although CBS made four announcements during the broadcast identifying it as a dramatic performance, at least one million of the estimated nine to twelve million Americans who heard it were deeply scared by that "Boo"—scared into some sort of action.

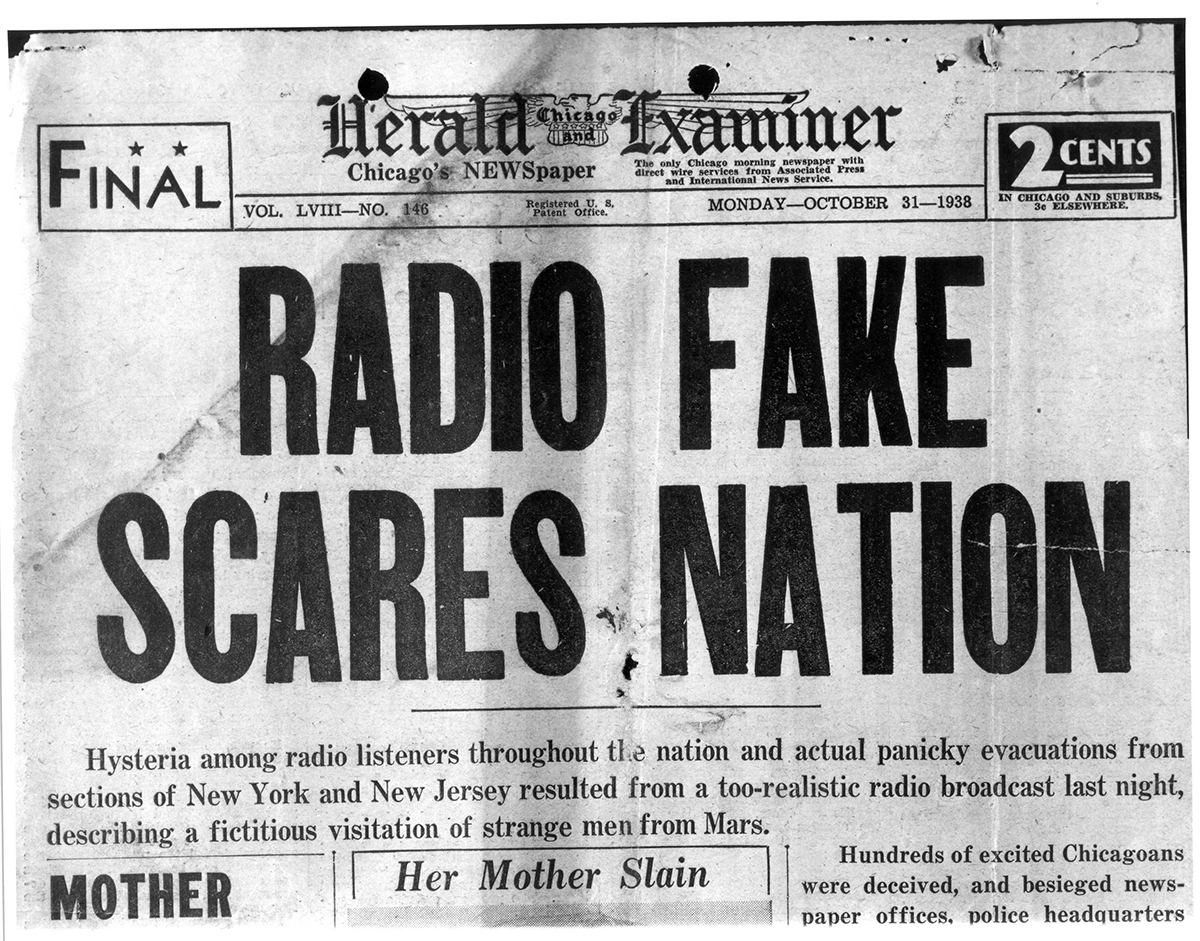

In the days following the broadcast, newspapers across the country described both the fear and the actions. Headlines proclaimed, "Mars Invasion in Radio Skit Terrifies U.S.," "H.G. Wells's Book and Orson Welles's Acting Bring Prayers, Tears, Flight, and the Police," "Radio Fake Scares Nation," and "Here's the Story That Scared U.S." News stories told of the behavior of listeners. Thousands, particularly along the eastern seaboard, had telephoned local police stations for confirmation. It was estimated that more than two thousand calls came in to New York's police headquarters within one fifteen-minute span. Listeners in areas far from the East Coast called, too—mostly to check on the condition of loved ones. Others telephoned one or more of the ninety-two stations that broadcast the performance. Some called newspapers—the New York Times switchboard counted 875 calls. Many people headed for local police stations; others loaded their families into their cars and drove away from the areas mentioned in the broadcast. There were numerous stories of traffic jams.

After the performance, hundreds of listeners vented their emotions in writing. For example, 1,770 people wrote letters to the main CBS station (WABC in New York), and 1,450 wrote to the Mercury Theatre staff.

And more than six hundred contacted the newly formed Federal Communications Commission (FCC). The letters, telegrams, and petitions to the FCC now reside in two boxes within Record Group 173, Records of the Federal Communications Commission, at the National Archives.

The FCC had been established just four years earlier, by the Communications Act of 1934, to regulate interstate and international communications. Its establishment reflected the growing importance of radio in American life. Although the law specifically prohibited the commission from censoring broadcast material or from making any regulation that would interfere with freedom of expression in broadcasting, these restrictions were either misunderstood or overlooked by nearly 60 percent of those who contacted the FCC.

Many of the writers asked FCC chairman Frank P. McNinch to "do what you can to stop H G Wells [sic] Mercury Theatre." Others encouraged the commission to prevent such broadcasts in the future and to punish Orson Welles. Claude W. Morris of Chicago told the commission, "I hope you will lawfully prevent such broadcasts in the future and, if possible, severely discipline all participants." Most of those who complained also shared personal stories with the commission about how the broadcast affected them, their families, or their communities. Claude L. Stewart of Meadville, Pennsylvania, sent a telegram to the commission stating, "Mercury Theatre of air not only in bad taste but dangerous stop my wife and several other women confined to beds from shock and hysteria." The city manager of Trenton, New Jersey, asked the commission to take action "to avoid a reoccurrence of a very grave and serious situation . . . which completely crippled communication facilities of our Police Department for about three hours."

One week after the broadcast, Hadley Cantril, a Princeton University psychologist, began a study of the panic caused by the broadcast. Over a period of about three weeks, Cantril and his research team conducted detailed interviews with 135 people, 100 of whom were known to have been upset by the performance. In 1940 he published his findings in The Invasion from Mars: A Study in the Psychology of Panic.

In the interviews, the listeners revealed many reasons for their fear. Some said it was because the performance did not sound like a play. Radio had become an accepted vehicle for important announcements. In recent weeks, listeners had become accustomed to having broadcasts interrupted by important late-breaking news related to Neville Chamberlain's meeting with Adolf Hitler in Munich, Germany. Others said their fear was caused by the prestige of the speakers. The fictitious characters included professors, astronomers, military officials, and even a secretary of the interior. Still others indicated that they could readily imagine the scenes that were described. The places mentioned were familiar, particularly to listeners in New York and New Jersey. And the actors repeatedly indicated difficulty in believing what they were seeing. The listeners could relate to their confusion.

In addition to Cantril's study, numerous other surveys were conducted following the broadcast. Two of the largest were by CBS and the American Institute of Public Opinion. They found that between 40 and 50 percent of the listeners had tuned into the broadcast late. Many had turned their dials away from the most popular program of the week, The Chase and Sanborn Hour, starring Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy, after the first act had ended. Others tuned in at the suggestion of neighbors or relatives who had called them regarding the Martian broadcast.

Not everyone who listened was scared into some sort of action. Many who were initially frightened simply looked outdoors, turned the dial to see if another station was carrying the "news," or consulted a newspaper listing that described the evening's broadcast schedule.

Millions of other listeners were delighted by the performance. Many of them, too, wrote letters. Of the 1,770 people who wrote to the main CBS station about the broadcast, 1,086 were complimentary. In addition, 91 percent of the letters received by the Mercury Theatre staff were positive. And roughly 40 percent of the letters sent to the FCC were supportive of the broadcast.

These letters focused on the entertainment value of the program, discouraged censorship, encouraged rebroadcasting the performance, and in many cases, offered sharp criticism of those who had complained. The singer Eddie Cantor sent a telegram to the FCC urging the commission to consider the future of radio as public entertainment. He stated that "the Mercury Theater [sic] drama . . . was a melodramatic masterpiece . . . censorship would retard radio immeasurably and produce a spineless radio theater as unbelievable as the script of the War of the Worlds." Rowena Ferguson of Nashville, Tennessee, encouraged the commission to consider the consequences of potential censorship by warning, "The evils of a [sic] censorship are more far-reaching and harder to handle than instances of error in judgement on the part of broadcasters." Mrs. Lillian Davenport of Texarkana, Texas, told the commission that "how anyone with the intelligence above that of a two-year-old child could be frightened by it is utterly incomprehensible." And J. V. Yaukey of Aberdeen, South Dakota, characterized the Mercury Theatre as a "radio high-light" and poked fun at some of the other listeners. He told the commission,

I suppose that by this time you have received many letters from numerous cranks and crack-pots who quickly became jitterbugs during the program. I was one of the thousands who heard this program and did not jump out of the window, did not attempt suicide, did not break my arm while beating a hasty retreat from my apartment, did not anticipate a horrible death, did not hear the Martians "rapping on my chamber door," did not see the monsters landing in war-like regalia in the park across the street, but sat serenely entertained no end by the fine portrayal of a fine play.

M. B. Wales of Gastonia, North Carolina, suggested to the commission that "if you take them [broadcasters] to task over this [the broadcast], won't you also have to stop fairy tales and stories about Santa Claus to keep a gullible public from becoming excited." Even children wrote to the commission. In a handwritten note, twelve-year-old Clifford Sickles of Rockford, Illinois, told the commission, "I enjoyed the broadcast of Mr. Wells [sic] . . . I heard about half of it but my mother and sister got frightened and I had to turn it off."

In the aftermath of the broadcast, The Mercury Theatre on the Air obtained corporate sponsorship from the Campbell Soup Company and became The Campbell Playhouse. Orson Welles received a multifilm deal from RKO Pictures. And ordinary citizens, the broadcast industry, and the government all gained a much deeper awareness of the power of radio.

A version of this article with teaching activities appeared as the "Teaching With Documents" feature in the May/June 2002 issue of Social Education, the journal of the National Council for the Social Studies. Since 1977, education specialists at the National Archives have been contributing "Teaching With Documents" articles to the journal, providing access to National Archives holdings and suggesting creative strategies for integrating primary sources into classroom instruction. For more information, write, call, or e-mail the Education Staff (NWE) at the National Archives and Records Administration, 8601 Adelphi Road, College Park, MD 20740-6001; 301-837-3478; education@nara.gov.

The author wishes to thank National Archives colleague Tab Lewis for his research assistance with this article.

Note on Sources

Letters and telegrams cited in this article are in the Office of the Executive Director, General Correspondence files, 1927–46, Records of the Federal Communications Commission, Record Group 173, National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

The main secondary sources consulted were Hadley Cantril, The Invasion from Mars: A Study in the Psychology of Panic (1940), Susan J. Douglas, Listening In: Radio and the American Imagination, from Amos 'N' Andy and Edward R. Murrow to Wolfman Jack and Howard Stern (2000); Ron Lackmann, The Encyclopedia of American Radio: An A–Z Guide to Radio from Jack Benny to Howard Stern (2000); David Thompson, Rosebud: The Story of Orson Welles (1996); Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich, This Is Orson Welles (1998).

The audio of the broadcast is available online from the West Windsor Branch of the Mercer County, New Jersey, Chamber of Commerce at http://www.westwindsornj.org/war-of-worlds-main.html.

Lee Ann Potter is the Education Team Leader in Museum Programs at the National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.