When FDR Said 'Play Ball'

President Called Baseball a Wartime Morale Booster

Spring 2002, Vol. 34, No. 1

By Gerald Bazer and Steven Culbertson

© 2002 by Gerald Bazer and Steven Culbertson

Like many other Presidents, Franklin D. Roosevelt loved baseball—even though he hadn't played it very well in his youth. As a school boy, he was once assigned to a team called the Bum Base Ball Boys, "made up of about the worst players."1 At Harvard, he ended up not as a player but as manager of the school's team.

Later, as a young attorney in New York City, he almost lost his job because he would sneak off to Giants games at the Polo Grounds.2 As assistant secretary of the navy during the Wilson administration, he substituted for the President in throwing out the first ball for the 1917 season. As President, he made a record eight opening day appearances.

So it should have come as no surprise that Roosevelt would come to baseball's defense when the question arose sixty years ago, soon after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, as to whether the "national pastime" should be suspended since the United States had become fully engaged in World War II.

Of course, the President declared, baseball should continue.

And so it did, throughout the war, even though most of its players, including some future Hall of Famers, traded their baseball cleats for combat boots and hoped that their prowess on the field wouldn't suffer during their time in service.

To Play or Not to Play?

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, America was in love with baseball, a welcome respite from the Great Depression and the war clouds forming over Europe. But many of the big stars of the 1920s and 1930s had already retired by the time fans bade a tearful farewell to the fatally ill Lou Gehrig, even as the stars of the 1940s and 1950s were emerging.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, which finally drew the United States into the world conflict, life in America changed. Able-bodied men were quickly being drafted into the armed forces, essential materials were being rationed, and priorities everywhere were shifting—from the highest levels of government to average families. Wartime required a change in the regular way of doing things, and people were willing to make sacrifices.

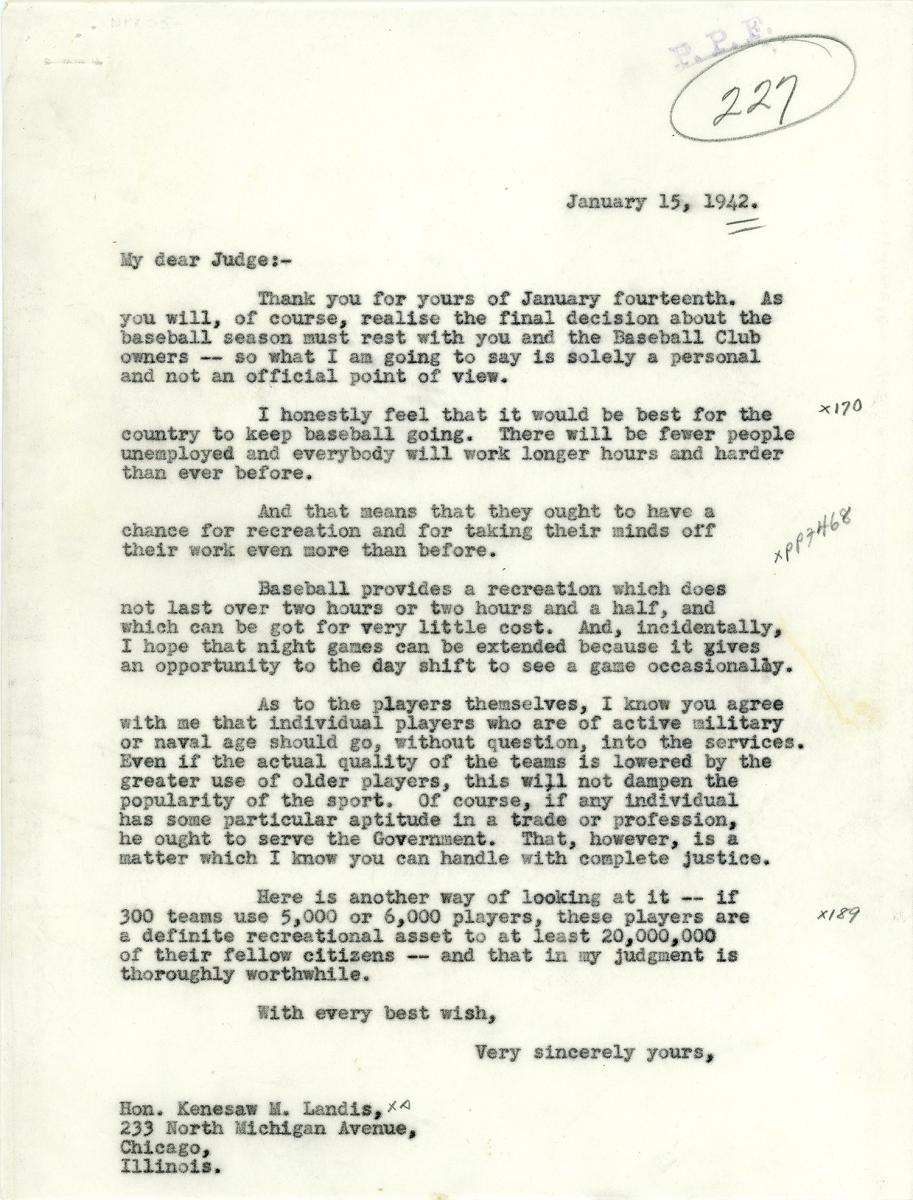

In January 1942, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the legendary commissioner of baseball, sent Roosevelt a handwritten letter, asking if major league baseball should be suspended for the duration of the war." The time is approaching when, in ordinary conditions, our teams would be heading for Spring training camps. However, inasmuch as these are not ordinary times, I venture to ask what you have in mind as to whether professional baseball should continue to operate," Landis wrote. "Of course, my inquiry does not relate at all to individual members of this organization, whose status, in the emergency, is fixed by law operating upon all citizens"3 Landis closed his letter: "Health and strength to you—and whatever else it takes to do this job."

Roosevelt's answer went out the next day. It left no doubt where the former "Bum Base Ball Boy" stood on the matter. "I honestly feel that it would be best for the country to keep baseball going," he wrote Landis in what has become known as "the green light letter." The President continued: "There will be fewer people unemployed and everybody will work longer hours and harder than ever before. And that means that they ought to have a chance for recreation and for taking their minds off their work even more than before."4

The President noted that going to a game was recreation that did not last more than two to two and a half hours and was not very expensive for Americans. "Here is another way of looking at it," he suggested. "If 300 teams use 5,000 or 6,000 players, these players are a definite recreational asset to at least 20,000,000 of their fellow citizens. And that, in my judgment, is thoroughly worthwhile." Roosevelt also asked if there could be more night games "because it gives an opportunity to the day shift to see a game occasionally."

The commander in chief also took on the issue of how many teams would be losing players: "I know that you agree with me that the individual players who are active military or naval age should go, without question, into the services. Even if the actual quality of the teams is lowered by the greatest use of older players, this will not dampen the popularity of the sport. Of course, if an individual has some particular aptitude in a trade or profession, he ought to serve the Government. That, however, is a matter which I know you can handle with complete justice."

In the end, however, Roosevelt left it up to Judge Landis and the club owners, saying his thoughts represented "solely a personal and not an official point of view."

As Roosevelt recommended in "the green light letter," baseball went on as scheduled in 1942, although FDR did not throw out the opening day first pitch as he had done eight times before.

A Green Light for the Debate, Too

Public reaction to the FDR-supported continuation of baseball—as reflected in public opinion polls and attendance figures—was generally favorable, but critics kept up the debate went on throughout the war.

Much of the continuing interest focused on players declared 4-F (unfit), or the possibility, quickly dispelled, that players would be declared to be in an essential industry, thereby freed from the draft. Criticism continued even though the armed forces had put uniforms on more than five hundred major leaguers, including most of the biggest stars, some of them just starting their careers—Ted Williams of the Red Sox, Stan Musial of the Cardinals, Hank Greenberg of the Tigers, Bob Feller of the Indians, and Joe DiMaggio of the Yankees—and four thousand minor leaguers.

An example of hostile comment was a letter to the editor in the New York Times on May 18, 1942, in response to draft boards' changing Class 1-A players to a lower status: "Don't they [baseball officials and draft boards] realize that our country is at war for the preservation of our rights and freedom and that we need all the manpower available both for active and noncombat service?"5 FBI director J. Edgar Hoover put to rest a lot of the concern, declaring, "If any ballplayer or other athletes were attempting to dodge service, it would be our job to look into such cases. But our records show there are few if any such cases among the thousands of ballplayers."6

Baseball's position throughout the war, with minor exceptions, was to emphasize that no special favors were being requested. Judge Landis was emphatic on the subject. "I have repeatedly stated on behalf of everybody connected with professional baseball that we ask no preferential treatment—that we would be disgraced if we got it."7

There was even criticism from within Roosevelt's own administration. James Byrnes, the director of war mobilization and reconstruction, questioned how players could be physically unfit for military service yet able to compete in games demanding physical fitness.8 Baseball responded by noting that they had much training room support not available in the military and, after all, they were found to be 4-F by army and navy doctors, not baseball's doctors.9

Baseball at the Battlefront

The U.S. armed services themselves seemed to have little problem with organized baseball continuing. Adm. Ernest King, commander in chief of the U.S. fleet, said "baseball has a rightful place in America at war. All work and no play seven days a week will soon take its toll on national morale."10

Indeed, baseball culture was evident on the war front. Soldiers used baseball lingo and facts when confronting suspected enemy infiltrators attempting to pass themselves off as allies. There were servicemen's teams across all theaters of war, and baseball was being played recreationally whenever ball diamonds could be carved out. Moreover, the services often utilized major league talent and staged interservice and intraservice championships.

There were lots of subscriptions available to Baseball Digest through contributions from fans at home who bought two subscriptions at reduced prices if one went to a serviceman.11 Also, part of many exhibition game gate proceeds went to such causes as Army-Navy relief funds.

Stars and Stripes and the British Broadcasting Corporation reported scores to interested listeners,12 and there existed a photograph from the Guadalcanal Gazette showing marines in the Solomon Islands studying their positions on the map while also studying baseball scores.13 Commissioner Landis recalled the wish of five soldiers, upon arriving home, for tickets to the next World Series and, poignantly, the question first asked of the Red Cross representative arranging prisoner exchanges, "Who won the World Series?"14

Although the loss of some good players affected the quality of play in the major leagues, the minor leagues were hit especially hard. Players with these clubs tended to be younger and with fewer dependents, thus making them more vulnerable to the draft. In 1940 there were 44 minor leagues with 310 clubs; by 1943, there were 9 leagues with 66 clubs.15

With many younger men in uniform, older players and those with numerous relatives dependent on them for financial support predominated. Even players thought of as infirm played, such as a one-armed outfielder and a pitcher with an artificial leg. Also keeping baseball in the public eye was the promotion of women's play, and one successful league lasted well into the 1950s. Meanwhile, the Negro Leagues flourished during the war, sometimes beating the major leagues in attendance. But the fact that whites and blacks were playing with each other on military teams did not translate into integration in major league baseball until years after the war.

Roosevelt himself continued to support baseball throughout the war. At a press conference just a month before he died in early 1945, he said, "I am all in favor of baseball so long as you don't use perfectly healthy people that could be doing more useful work in the war. I consider baseball a very good thing for the population during the war." Asked if he thought that definition would take too many people out of baseball and make it hard for the "big leagues" to operate, he responded:"Why not? It may not be quite as good a team, but I would go out to see a baseball game played by a sandlot team—and so would most people "16

A month later, Roosevelt died as World War II neared its end. And in the months ahead, future legends returned home to trade their military uniforms for leather mitts and ball caps. And ex-soldiers named DiMaggio, Williams, Musial, Greenberg, Feller, and others resumed their journey to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Gerald Bazer is dean of arts and sciences at Owens Community College in Toledo, Ohio. He has contributed several journal and newspaper essays discussing which American Presidents have been considered our greatest. This essay combines his two passions: the American Presidency and baseball.

Steven Culbertson is currently professor of communications/humanities at Owens Community College in Toledo, Ohio. He received his Ph.D. from Bowling Green State University.

Notes

This article is based in large part on a presentation by Gerald Bazer and Steven Culbertson made at "The Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, 2000," at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, N.Y., in the spring of 2000. Papers from that symposium are printed under the same title in a book with William M. Simons as editor and published by McFarland & Co., 2001.

1 Peter Collier and David Horowitz, The Roosevelts: An American Saga (1994), p. 105.

2 Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns, Baseball—An Illustrated History (1994), p. 276.

3 Kenesaw Mountain Landis to President Franklin Roosevelt, Jan. 14, 1942, President's Personal File 227: Baseball, folder: 1939–1945, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library (FDRL), Hyde Park, NY.

4 Roosevelt to Landis, Jan. 15, 1942, ibid. A carbon copy is at the library, and the original that Landis received is in the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, NY.

5 Letter to the editor, New York Times, May 18, 1942, p. 18.

6 Bill Gilbert, They Also Served: Baseball and the Home Front, 1941–1945 (1992), p. 4.

7Quoted in Paul Dickson, Baseball's Greatest Quotations (1991), p. 235.

8 Gilbert, They Also Served, p. 172.

9 Richard Goldstein, Spartan Seasons: How Baseball Survived the Second World War (1980), p. 199.

10 From Dickson, Baseball's Greatest Quotations, p. 222. Quoted in Baseball Digest January 1943.

11 Advertisement in Baseball Digest, September 1943.

12 New York Times, Aug. 8, 1942, p. 2.

13 Ibid., Sept. 25, 1942, n.p.

14 Goldstein, Spartan Seasons, pp. 40, 41–42.

15 Patrick J. Harrigan, The Detroit Tigers: Club and Community 1945–1955 (1997), p. 288.

16 Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt, vol. 13 (1950), p. 592.