Band of Angels

Sister Nurses in the Spanish-American War

Fall 2002, Vol. 34, No. 3

By Mercedes Graf

© 2002 by Mercedes Graf

Although thousands of patriotic women rushed off to care for the sick and wounded during America's bloody Civil War (1861–1865), only a very few were trained in the medical arts—and they were Catholic nuns.1

Doctors, of course, preferred to have trained nurses caring for the sick and wounded. But having nuns as nurses was even better because "the special characteristics of their lives enabled them to function as a cohesive group, to accept difficult physical and material circumstances, and to relate to the soldiers in a nonsexual, even-handed manner."2 Religious women also came from a hierarchical structure where they were used to self-discipline and understood self-sacrifice and obedience to authority. The presence of these well-prepared individuals demonstrated the advantages of having trained nurses on duty during wartime.

Nearly four decades later, in 1898, U.S. soldiers went into battle again in the Spanish-American War, which marked America's debut as a world power seeking to expand its influence. After the outbreak of war in April 1898, U.S. forces quickly subdued the Spanish in the Philippines, then moved on to Cuba. Within months, they overwhelmed the Spanish, and Theodore Roosevelt gained fame that would lead him to the White House.

Despite the lessons learned in the Civil War, the government had taken no concerted steps toward establishing a skilled nursing service to care for the sick and wounded during wartime. Although enlisted men from the U.S. Army Medical Department served in the Hospital Corps, the numbers were insufficient, as there were less than 800 men—99 hospital stewards, 100 acting stewards, and 592 privates. On June 1, 1898, Congress increased the number of hospital stewards to two hundred.3 But most of the Hospital Corps men who enlisted or who were detailed from combat regiments had little or no proper training as nurses. And when their regiments were moved, detailees were called back to duty.

The war with Spain was quickly demonstrating the important need for trained nurses as hastily constructed army camps for more than twenty-eight thousand members of the regular army were devastated by diarrhea, dysentery, typhoid fever, and malaria—all of which took a much greater toll than did enemy gunfire.

As a result, the need for trained nurses was heightened—and the work of the sister nurses in the Civil War was not forgotten.

The Need for Nurses

While the importance of well-trained female nurses had been demonstrated in civilian hospitals for at least two decades before the Spanish-American War, there were still many military and medical men who questioned whether a field hospital was any place for a woman. Although the surgeon general of the army initially opposed having women in the field, he believed that that they would be needed as nurses and dietitians at base and general hospitals. He obtained authority to appoint both men and women nurses as civilian employees under contract with pay allotted at thirty dollars a month, meals, quarters, and traveling expenses. At the same time, Dr. Anita Newcomb McGee, vice-president general of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) offered to examine all applications referred by the government from women. Even as the surgeon general of the army immediately accepted this offer, his counterpart of the navy joined him, and DAR associates were appointed to help in the selection process. The enormity of this work should not be underestimated, as during the month of May 1898 alone, applications were received from 2,353 women.4

All applications were forwarded to Dr. McGee, who was left free to set her own standards.5 To be placed on the eligible list, a nurse must have been graduated from a training school and have the endorsement of the present superintendent of that school or the one under whom she was trained. The original age limit was thirty to fifty years, but exceptions soon had to be made in view of the huge demand for nurses. A requirement that had not been demanded at the outset, but which became immediately apparent, was a physician's certificate stating that the applicant was well and strong enough for army duty. By August 3l, 1898, there were almost a thousand nurses under contract, with the demand still growing in view of the terrible epidemic of typhoid fever that raged that summer in the camps.

A different sort of recruitment effort was made in July 1898. Under the direction of the surgeon general of the army, Mrs. Namah Curtis had been sent in July to secure the service of immune colored women (living mostly in the South), who could serve as nurses at Santiago, Cuba, to tend yellow fever patients.6 These women were selected for the job mainly because they had already survived yellow fever, but the majority of them were not trained nurses.7

Sisters Answer the Call

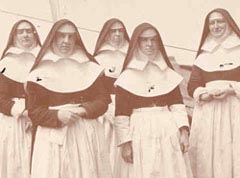

As a result of their work in the Civil War, religious sisters were recognized for providing skilled nursing services. In view of the urgent need for medical assistance in the summer of 1898, it was no surprise when the government called for every nursing sister who could be spared. Official government records indicated that the various orders furnished around 250 sister nurses, with the Daughters of Charity (originally referred to in the United States as Sisters of Charity), providing the majority of nurses.8 Although members of other orders were represented, their numbers were considerably less.9

This article focuses on the different orders of nursing sisters and on their experiences and difficulties encountered during the Spanish-American War. Each section below will describe a particular group and their contributions, starting with the Daughters of Charity, which sent more than two hundred women, and continuing to the smaller orders, which sent anywhere from four to just over a dozen sisters.

Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul, Emmitsburg, Maryland

On April 23, 1898, the Daughters of Charity, sometimes referred to as the Cornette Sisters because of their large white linen headgear, offered their services to the government much as they had done in the Civil War.10 During that conflict, they had compiled a proud record of tending the wounded at Satterlee Hospital in Philadelphia, where more Union wounded had been treated than at any other hospital during the war. Now, with their official entry into another conflict, sisters were called from the various missions throughout the country, and the motherhouse in Emmitsburg became the focal point for these nursing sisters. Originally one hundred sisters were promised, but in view of the desperate plea for more help, just over two hundred women eventually tended the sick and wounded.11 As a result, "many of those later sent were not so thoroughly qualified as were the Sisters in the early parties."12 Those who had limited nursing experience assisted the more experienced when needed.

As the nuns made their way to the camp hospitals, Reverend Mother Mariana Flynn, head of the order, stated that her sisters were "back in the army again, caring for our sick and wounded."13 The nuns were dispatched to numerous locations, mostly in the southern United States: the Norfolk Naval Hospital, Portsmouth, Virginia; the Third Division Hospital, Chickamauga Park, Georgia; Seventh Army Corps, Jacksonville, Florida; Camp Poland, Knoxville, Tennessee; Hospitals of the Fourth Army Corps, Huntsville, Alabama; Camp Alger, Second Army Corps, Falls Church, Virginia; U.S. Army General Hospital, Fort Thomas, Kentucky; Camp Wikoff, U.S. Army General Hospital Annex, Montauk Point, Long Island, New York; and Camp Cuba Libre, First, Second, and Third Division Hospitals. The sisters' last assignment was at the Military Hospital, Ponce, Puerto Rico, where nineteen of them were stationed for three months nursing sick American soldiers until the last days of January 1899.14 While it is evident that the Daughters of Charity served at numerous sites, only some highlights about their service will be presented here.

Work at the Naval Hospital

Before the first formal requisition could be processed for the sisters' service, a request came from the physicians in charge of the Norfolk Naval Hospital at Portsmouth, Virginia, for five sisters to come there and serve as night nurses.15 All of the women who eventually served there were skilled nurses.16 One of the nuns spoke Spanish, and she wrote: "I am very thankful to the Lord for my Spanish, for it is as great consolation to these poor prisoners, to talk in their own language and tell their troubles and fears to someone who understands what they say."17

While there were some Spanish prisoners at the hospital, the majority were American patients who were recovering from their wounds or had typhoid and malarial fever or pneumonia. In addition, there were ten measles cases in the "pest house," where one male nurse had been assigned to duty. Sister Salazar described cases of serious burns as well as amputations. In fact, one man who had to have his leg removed was "too weak to bear the operation," and the burn case, while alive, was suffering a great deal.18 Sister Salazar's letter further indicates that the sisters were so well experienced that they functioned as surgical nurses, unlike in the Civil War, when the majority of women were untrained. Indeed, the doctors were extremely satisfied as the sisters not only reduced the anxiety and responsibility connected with their work, but they could "be relied on at all times."19

In recognition of their work at the naval hospital, the sisters received an official letter of acknowledgment from the surgeon general of the navy. He felt that the women were to be particularly congratulated for their "kind, faithful, and efficient help and nursing . . . which looks not for earthly praise but has its reward in alleviating suffering, as leading mankind to a better and higher life."20 The sisters' work at Portsmouth demonstrates that a small handful of contract nurses served the navy.

Work at Camp Wikoff

When the motherhouse at Emmitsburg, Maryland, received the government's request for help in caring for the sick and wounded, thirty-seven nuns volunteered on August 18, 1898, to go to Camp Wikoff, Montauk Point, Long Island. By war's end, 112 sisters served there.21 Government records noted that the sisters were frequently forced to go on furloughs because they had overworked themselves to the point of exhaustion between assignments. For example, Sisters Ligouri McClery, Ambrosia McDevitt, Marie Hall, and Margaret Garvey had all just returned from furloughs before being sent on to Montauk.22 Accounts from the period indicate that conditions at Camp Wikoff were less than desirable during the first two weeks after it was established. With the surrender of the Spanish forces at Santiago and the subsequent rapid increase of sickness in the regiments of the Fifth Corps, the army withdrew troops from Cuba and sent them to the quarantine station at Montauk Point. This site was chosen because it was easily accessible by water, and its isolated location lessened the possibility of spreading yellow fever beyond the camp.

By August 5, 1898, work began on building five detention camps for a thousand men each, with hospital accommodations for five hundred. All the men returning from Cuba had to pass through here. At the same time, a general camp of new tents intended to shelter eight to ten thousand men was rapidly constructed. The work of preparing the camp had hardly commenced, however, when on August 7 troops began to come in from Tampa and other places in the southern states. Within forty-eight hours, 4,293 men arrived, along with seven or eight thousand horses and mules. The first of these troops arrived without tents or equipment of any kind and with only travel rations.

Because of inadequate transportation at the camp, supplies were not delivered promptly, and the transfer of sick and convalescent men from the vessels to the camp was at times slower than it should have been. Sanitation for the camps and hospitals was generally acceptable but could have been improved.23

As the sick soldiers started arriving, the surgeons found it necessary to relieve the overcrowded wards by sending many of the men off prematurely. The nursing staff was similarly overtaxed. One of the sisters wrote: "We have hardly time to eat or pray, it is all work, and rush rush at that. The soldiers are constantly coming."24 Another Sister of Charity explained to the Mother Superior:

We are more than busy (if such can be) but all well. . . . Our camp is being enlarged every day. Last night we opened four more immense wards— one surgical ward too. I had to go around stealing the Sisters from other wards to supply these and had a time pacifying two doctors who were unwilling to give the Srs. up. . . . Some of the men want to know how the sisters manage and how they can stand, for they never see them eat, sit down or sleep.25

One newspaper reporter related that all the nurses worked night and day, contenting themselves with poor meals and poor beds while the men whom they cared for got every attention they could bestow. "The sisters from various Catholic institutions are doing especially good work, not that their will is any better than the other noble women who are working here, but because they are better trained and seem to have a sympathetic intuition that guides them at all times."26

After making a personal visit to the camp in September, Dr. Anita Newcomb McGee found the sisters "shamefully overworked" and asked for forty-five more. Her representative requested that these women be regular hospital sisters "who could do anything from giving a hyperdermic [sic] up and down; for owing to a condition of administration, and discipline(!) which it is not prudent to speak of and which is being made the subject of official investigation the life of the patient hangs on the nurse's knowledge."27

It was not long before the nuns fell ill themselves. One member of the order wrote to the motherhouse: "Sister Alice Gannon has been ill for four days. I thought it was only what all the others had—diarrhea. But instead of getting better she is worse and Sr. Cornelia fears typhoid. I dispatched to you to know what to do. Sister is bent upon going home."28 Sister Agnes (Mary Sweeney), who was also at the camp, served as a night nurse. When Camp Wikoff broke up, she went on to Jacksonville, Florida. She was finally forced to take a furlough on October 8, and she was brought to St. Joseph's Hospital ill with typhoid. But she was not constitutionally strong, and when complications set in, she succumbed to the fever and died.29 After leaving Montauk Point, Sister Mary (Anne Larkin) was sent to the General Hospital at Ponce, Puerto Rico, where she became ill and died of typhoid fever.30 Sister Caroline (Caroline Wolfe) also died while in service on October 15, 1898, from typhoid.31 Sister Mary Anastasia (Mary Ellen Burke) gave up her life to the same fever.32

In summarizing their heroic work at Camp Wikoff, one newspaper reported that it would be useless to detail "the self-sacrificing manner in which the sisters labored for the sick soldiers. Most of them are women of refinement and station. While at the camp they did the most menial work, acting as ordinary nurses and attending to the wants of the patients both by day and night."33

Experience at Santiago

The government asked for twelve Daughters of Charity to nurse the sick and wounded soldiers at Santiago, Cuba.34 The request called for those nuns who had previously been exposed to yellow fever and were therefore "immune" from it. When the sisters embarked from the boat at Santiago on the morning of August 19, 1898, a tug took them to the convent of the Sisters of Charity there. The sisters, who were preparing to leave and go back to their native Spain, thought the new arrivals had come to replace them and take charge of the hospital with its Spanish prisoners. The American sisters, however, pointed out that they had come to nurse U.S. soldiers who were ill at Camp Siboney. Sister Mary Carroll reported:

We saw General Schaffter and Dr. Harvard but neither of them would be willing for us to go to the camp. In fact they said it would be impossible for us to live there. They sent an officer with us to the Hospital, a building containing 235 patients men, women and children, not a person in the house spoke or understood a word of English. As soon as we went there the Sisters began to pack their trunks. We tried to make them understand that we could not take charge of their hospitals without the authorization of superiors, that we only came for American soldiers as long as they needed our services, and were then to return home. . . . It seems like an age since we left New York and yet we only spent one night in Santiago.35

If it seemed at first that the long journey had been wasted as the sisters were not allowed to do nursing in Cuba, they soon learned there was more than enough to do. Gen. Leonard Wood, the military governor, ordered the sisters to return on the transport Yale, which was carrying thirteen hundred sick men back to the United States, many suffering from fever and bowel problems. Immediately the sisters began to divide themselves up so they could care for the men and try to make them as comfortable as possible. On their arrival at Camp Wikoff, they continued their work with the sisters who were already stationed there. About twenty thousand patients were treated in the tent hospitals before war's end.

Chickamauga Park

Conditions at Chickamauga were so primitive that when the nuns arrived, a few boards were placed on the ground to form a kind of platform where they could rest. One sister recalled: "Each one put her package down, not having any place to sit, each sat on her satchel. I think the number was twenty-four, we were tired, sleepy, and dirty, but a little while and we all went to work to clean a kind of shed made of green wood for a dormatory [sic]; we were glad enough when six o'clock came, as we got something to eat. . . . We certainly did look like soldiers, for we had no bedding, simply a blanket, one half under us, and the other over us, with one pillow."36

The facilities at the camp were almost always overcrowded, officers in charge were frequently changed, and nurses were limited in number. In addition, medicines, hospital supplies, and furniture were lacking, to say nothing of the day-to-day predicaments that staff encountered. One nurse lamented: "Foremost in my mind are those insects, the innumerable flies. They settled everywhere. Our food was covered with them. Before partaking of meals, we were obliged to shoo them off with force and when they did let go, the tugging was nauseating"37

Even before the Sisters of Charity arrived, the chief surgeon telegraphed to the surgeon general on April 25, 1898:

Have inspected whole command. Three regiments and six batteries have no medicines nor supplies of any kind. Must have more medical officers at once. Dispatch chests of all kinds, field furniture at least. Send 100 bedsacks, 100 blankets, 12 field desks, and blankets of all kinds. Send stewards and hospital corps privates.38

Maud Cromelien, who was with the Red Cross auxiliary for the maintenance of trained nurses, described the suffering as great while "the neglect was greater. . . . Hospital stewards were overworked, as well as nurses; orderlies were scarce and the rush of patients from the surrounding hospitals was unceasing. . . . And it must be remembered," she pointed out, "the patients came in suffering from starvation, covered in some cases with lice and maggots, mouths crusted and sore from neglect, bed-sores that were sloughing and deep."39

The first week of September, there was a heavy rain, "which made sad havoc among the tents." One sister who signed her letter "Your Children of the Battlefield" remembered how the rain, falling in heavy torrents and soaking through the tents, awakened many women from their sleep and "obliged them to change every piece of clothing." In the morning they were informed that the kitchen had blown down during the night, so they were obliged to eat standing up in what was left of the refectory. Yet the sisters never lost their sense of humor, for they reported: "The picture presented at that breakfast table will not soon be forgotten, one could not but smile at the many different shapes the Cornettes had assumed, not any two were alike; yet if there was no uniformity in the head dress, there was in the countenances for each face beamed with joy, revealing the happiness to be experienced in performing acts of charity in the midst of privations."40

As the days passed, the work of nursing went on, and a few of the nuns became ill or suffered from dysentery and sick stomachs. "The surroundings at the hospital are simply horrible," Sr. Mary Stella confided in a letter to the Mother Superior. "Sister Aimee is on the sick list— was not able to attend Mass. I fear she will not be able to stand the exposure of camp life."41 Another sister reported: "Many of the SRS sick, but nothing serious, only fatigue and exposure, the distance from sleeping sheds to Corps tents near a mile, umbrellas and overshoes in constant requisition."42 By the end of September, however, more sisters became ill. A letter sent to the motherhouse noted that "Sr. Berchman coughs very much, she is good and generous, she does not complain, never lost a day and does not attach any importance to her cough. . . . Sr. Stella told me to say that Sr. Josephine Browne is looking very badly—she does not look able for much more hardship or exposure."43

Mindful of the sacrifices that the nuns were making, one of the surgeons wrote to Mother Mariana tendering his hope that the sick sisters were fully recovering. He also complimented the order for the work done at the various hospitals in Chickamauga Park, Georgia.

I can hardly tell you in words strong enough how much of an assistance and comfort they have been to me. I worked hard for them, and they did the same for me, never failed me. They took supurb [sic] care of their patients; they helped me in every department of my Hospital, and if it was a success, a great deal of the credit is due to them. I am waiting here to-day for orders, nearly a tired out man, but I should feel it a dereliction of duty if I did not tell you how nobly they responded to every demand made of them.44

Elsewhere the sisters continued their heroic labors at the numerous camps mentioned above. When Camp Wikoff closed, the nuns were ordered to Huntsville, Alabama. Upon their arrival, some of them found orders that directed them to duty at Jacksonville, Florida. At Huntsville, the sisters cared for the sick soldiers at the Fourth Corps Reserve Hospital, Camp Wheeler, and also at the Field Hospital, Second Brigade, Second Division, Fourth Army Corps. When the camp at Chickamauga Park was shut down, sisters were transferred for duty to Camp Poland, Knoxville, Tennessee, and Camp Hamilton, Lexington, Kentucky. By the end of August, twenty sisters were asked for at Camp Alger in Falls Church, Virginia, but only ten were allowed to remain there when problems arose because of the commanding officer's anti-Catholic attitude.45 This problem was not entirely unexpected as sisters in many of the camps met with religious prejudice. The hospitals in Knoxville and Lexington, however, closed in the latter part of September 1898, and the sisters prepared to go back to their respective convents. By November 1, all sisters had left the camps and returned to their missions.

Sisters of St. Joseph

The Sisters of St. Joseph were founded in Le Puy, France, on October 15, 1650. In 1836, six sisters left France and settled in Carondelet, Missouri. From there, the Sisters of St. Joseph were established in many areas of the United States. They founded hospitals in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Wheeling, West Virginia.46 Sisters of this congregation also rendered aid and comfort to afflicted soldiers in their own hospital during the Civil War when it was leased to the Union government as a military hospital.

During the Spanish-American War, eleven of these sisters served at Camp Hamilton, Lexington, Kentucky; Camp Gilman, Americus, Georgia; and Matanzas, Cuba. Sisters from the various orders, however, frequently served in some of the same camps. As a result, the Sisters of St. Joseph were closely associated with the Sisters of the Holy Cross and the Daughters of Charity from Emmitsburg. Mass was said daily when possible, and their work was lightened by having contact with other community members who often encountered the same problems.

At Camp Hamilton in Kentucky, for example, Sister Bonaventure wrote: "One of the Holy Cross sisters was taken to the Hospital in Lexington last Sunday. Her temperature when she left camp being 104."47 On another occasion, a Sister of St. Joseph noted: "We have not been as long in the field as the Sisters of Charity and Holy Cross; they are nearly all broken down, poor things, but they know how to get along better than we. Some of them have experience of this kind of life."48

Personal Data cards were located for all eleven of the nuns who listed their residences in Missouri and Minnesota.49 Their nursing experience ranged from six months to twenty-one years. Sr. Mary Bonaventure explained that her hospital experience had been limited to one year because she had been teaching school. Many of the other sisters specified that their work had been "medical and surgical," making it quite clear that they were well qualified to take on the duties of army nursing. The youngest was twenty-eight, and the oldest was fifty-one years old, and with the exception of three sisters born in Ireland, all the rest claimed the United States as their birthplace.

In some instances, comments written on the Personal Data cards testified to the services the sisters provided. They were described as "thoroughly satisfactory in every respect," and ratings of excellent were awarded them for both health and ability. The Personal Data card for Sr. Mary Liguori (McNamara) reports that she was "an excellent and exemplary woman and satisfactory in every respect. Has tact and good judgment, and is respected and liked by all."50

Sister (also referred to as Mother) Liguori, superior of St. Joseph's Hospital in Kansas City, was chosen to lead the first small band which consisted of experienced nurses. Under her charge, the group left Carondelet on September 14, 1898, and after taking the oath of allegiance to the United States at Camp Hamilton, they found themselves in a city of tents that held nine thousand men. Their own quarters were close to those of the Sisters of Charity from Emmitsburg and the Sisters of the Holy Cross. Night and day the nuns relieved each other in the wards, "their labors sweetened by the kind and helpful intercourse of the communities, one with the other, and rewarded by the restoration of health of by far the greater number of their patients."51 Many of these were mere youths who had been overcome by fever and nostalgia. Yet all the soldiers were grateful for any service that made their surroundings more homelike. All in all, five hundred men sick with typhoid fever claimed the time and attention of the one hundred nurses in charge, forty-eight of whom were religious.

As the Sisters of St. Joseph tended the sick, they also had to deal with the constant rain and its problems. "The mud, is something terrible," Sister Liguori wrote. "At night it is so dark, but we have lanterns to light our path. Sr. Irmina went up to her knees in a mud hole last night."52 She also commented on the constant cold and the need for winter shawls and flannels. Finally, she brought up a delicate question in her letter to the motherhouse. "Do you think it would be advisable if I could get a little whiskey. The night nurses are so chilled when they come home in the morning that a little hot toddy would warm them up before they go to bed."53 A week later, it appears that the nun got her answer from the Reverend Mother, as she wrote back: "Dear Mother, how to thank you for sending the whiskey, but my, what will we do with 2 gallons. Why, one pint would be all we want and maybe we would not need that."54

From the camp in Kentucky, the band of now ten women (since one nun had been recalled to St. Louis) went on to Camp Gilman in Americus, Georgia. Here there were 150 sick soldiers to care for daily, and while the difficulties associated with camp life continued, the sisters all remained in excellent health. Furthermore, they were treated extremely well by the officer in charge of the camp, who had the highest respect for the sisters and could not do enough for them. The rations were good, better than at Camp Hamilton, although the army furnished no butter or milk. "We have had out trials and crosses to contend with but . . . this is army life and we do not find it hard to live up to the rules," Sister Liguori explained.55

By the beginning of the new year, the sisters were told to ready themselves for their third assignment at Matanzas, Cuba. At the sisters' pleading, they were allowed to remain to prepare Christmas dinner for their patients before boarding a transport ship in Charleston, South Carolina.

The nuns arrived at Matanzas Bay on January 1, 1899, although they remained on ship until January 6, riding in an army ambulance to Mass in a Spanish hospital each day. Once on land, they assumed charge of a government hospital where they continued their work of mercy. In addition, they opened up a diet kitchen for the patients. Now, however, the nuns encountered intense heat during the day as opposed to the extreme cold they had endured in Kentucky. There was also a problem with an unwelcome invader: "The nights are cool," sister observed, "but the fleas have us about devoured."56

By March, word of their good nursing care had spread across Cuba. Sister Liguori wrote: "The fame and neatness of our Hospital has gone all through Camps on the Island. . . . Do not think, dear Mother, we are carried off by all this flattery. No, I am thankful to say it makes us humble, thank God."57 By April, the nuns eagerly awaited the hospital ships that were to pick up the soldiers. Sister Liguori, however, was ill with a case of yellow fever and quarantined alone in a tent on the roof of the hospital. Yet she wrote not of her own isolation but of the feelings of her soldier patients. "They are so homesick for their homes. It cheers them up, the poor soldiers, when they hear of home and going back to the States. When the transport arrives you will hear nothing but cheers, 'Home, Sweet Home,' and 'The Girl I left Behind Me.'"58

In April 1899, the sisters resigned from their contracts as there was no further need of them, although they continued their service among the sick and wounded until May 10, 1899, when they set sail for New York.59 At the same time, U.S. military authorities in Matanzas wanted Americans to oversee an orphan asylum there and urged the sisters to remain longer and direct it, but the Reverend Mother Agatha did not consent to this plan because it was not approved by the archbishop. By the time they arrived home, the nuns had seen eight months of hard duty.

The Sisters of Mercy

The Order of Mercy was founded in Ireland on the banks of the Liffey in 1831, although the beginnings of the Baltimore congregation date back to the year 1852 when application was made to the bishop of Pittsburgh to take charge of a hospital in Washington, DC. By the end of the Civil War, Mercy's war nurses left a proud record that started when Secretary of War Edwin Stanton invited the sisters to care for soldiers sent to Stanton Hospital in Washington, D.C.

With the outbreak of the war in Cuba, the Sisters of Mercy of Baltimore responded to the call again by sending a small contingent with Sr. Bernard O'Kane, who had nursed in the Civil War at the Old Armory and Douglas Hospital.60 She and twelve companions were ordered to Camp Thomas in Chickamauga Park, Georgia.61 Sr. Nolasco McColm, who had been a pharmacist at Mercy Hospital, kept a diary about her experiences that commenced on August 20, 1898, when the sisters left Baltimore for a train ride that lasted twenty-seven hours before they arrived at Chickamauga.

The harsh conditions at Camp Thomas affected both patients and nurses alike. A Baltimore newspaper reported that Sr. Mary Flanagan fell victim to typhoid fever while on duty in the camp.62 She had actually become ill at Camp Poland in Knoxville, Tennessee, where she had been transferred in the middle of September after serving at the General Hospital in Chickamauga. The article further disclosed, "several others were dangerously ill, their lives being for a time despaired of, but these eventually recovered or are now convalescent."

Through September of 1898, the Sisters of Mercy also nursed alongside other community members at camps located at Knoxville, Tennessee, and Columbus, Georgia, and a group from San Francisco cared for the sick and wounded at the Presidio. In 1921, the eight sisters who were still alive were awarded service medals.

Sisters of the Holy Cross

The Congregation of the Sisters of the Holy Cross was founded in 1841 in LeMans, France, but sisters came to the United States two years later. Although they were not a nursing order, they had nursed on the battlefields during the Civil War. As four of them were known to have cared for wounded on the transport Red Rover, these sisters are often considered the forerunners of the U.S. Navy Nurse Corps. After the war ended, they established hospitals in Idaho, Utah, Ohio, Illinois, and Indiana.

When the DAR representative, Ella Lorraine Dorsey, wrote to the Mother General at Notre Dame, Indiana, requesting sisters for nurses in the Spanish-American War, twelve sisters of the Holy Cross from South Bend, Indiana, made their way again into the service of their country. Two of them, Sisters Valentina and Emerentiana, were not trained nurses but were sent to assist in any way possible.63 After signing their contracts, the nuns were immediately dispatched to the Third Division Hospital at Camp Hamilton, Lexington, Kentucky. In late November 1898, they were dispatched to the First Brigade Hospital at Camp Conrad in Columbus, Georgia.

When the Columbus Hospital was closed, the sisters were ordered to Matanzas, Cuba. On January 14, 1899, they boarded the transport ship Panama at Savannah, Georgia. Unfortunately, when they arrived, they learned that they were to return on the same transport that had just brought them, as their services were no longer needed (a similar experience to that of the Daughters of Charity in Santiago a few months earlier).

While the record of these sisters has been detailed elsewhere, not enough can be said about their dedication and sacrifices.64 In short, as the nurses battled typhoid fever, they were responsible for managing and maintaining the environment of the sick wards. They were in charge of the diet kitchens, and they assumed the routine tasks of changing the linen, bathing the patients, and even writing letters home for them. Never did they waver in their untiring care of their patients throughout their grueling hours of hard work. Some of the nuns themselves became ill, a sad fact that was true for many nurses, whether lay women or religious sisters.

Personal Data cards were located for eight of these religious women: Sr. Galasia Baden, Sr. Lydia Clifford, Sr. Joachim Casey, Sr. Genevieve Conway, Sr. Camillas McSweeney, Sr. Cornelius McCabe, Sr. Florentia Stack, and Sr. Valentina Reid. These sisters ranged in age from twenty-nine to forty-four and were born in Ireland and the United States, coming from Maryland in the southeast to Utah in the far west. All eight indicated that they had prior nursing experience of from one to ten years. Seven of the sisters had their contracts annulled in January or February of 1899 when their services were no longer needed. Sister Reid went on sick leave from November 30 to December 29 of 1898 before her contract was annulled early in January "on account of illness." All of them indicated that they were strong and healthy and able to leave immediately for duty.65

One writer concluded that the Sisters of the Holy Cross "performed valuable services in camp hospitals as well as on the train or ship, and they provided their own hospitals for the care of sick soldiers."66 In postwar years the nuns established eight nursing schools, three of which were initiated by sisters who had labored in the Spanish-American War.

Cuban Sisters of Charity

Government records listed twelve Cuban Sisters of Charity who also tended to the wounded.67 Personal Data cards were located for three of these women: Sisters Simona Galarza, Josefa Guarnero, and Mercedes Civit.68 All of the nuns revealed they had prior nursing experience that ranged from thirteen to fifteen years. After signing their contracts, the first two sisters were assigned to Military Hospital No. 1 in Havana, Cuba, where they remained until their contracts were annulled ten months later. This hospital was the chief military hospital of Cuba under the Americans, as it has been under the Spaniards, when it was called Hospital Alfonso XIII.

Years later, the chief surgeon remarked:

There was very little sickness among them, considering the amount of work, loss of sleep, anxiety, mosquitoes, and hot weather, to which they were subjected . . . they proved a veritable blessing to the overworked medical officers, saving them much time, relieving them of much anxiety, and preventing them being turned out unnecessarily at night.69

At Las Animas, the yellow-fever hospital in Havana, "the work of these nurses was both arduous and dangerous."70 It was to this civilian hospital that Sr. Mercedes Civit was sent and where she remained one month before her contract was annulled.71 Miss Turner, another nurse at Las Animas, explained how three different buildings were used as wards: one for suspects, one for acute cases, and the other for convalescents. "The first two were houses and well suited to the work, as a constant moving and shifting was necessary in order to keep those very ill or dying from the others. . . . We had twelve hour duty, which meant about thirteen, as it was impossible to have our charts in order with all the work there was to do."72

Since the care of patients with yellow fever generally followed a prescribed regimen, we can assume that Sister Mercedes not only knew the specific action to be taken as the various stages of the illness progressed, but that she was responsible for treating soldiers under her care. At the onset of the disease, a purgative was administered to rid the body of systemic toxins while high fever was treated with cold sponging, baths, and large iced-water enemas. Mouths had to be cleaned thoroughly and frequently, owing to the constant bleeding of the gums. As it was impossible for patients to take or retain medicine, two enemas of plain faucet water were given daily. It was said that "the onerous work of making the patients' lives less wretched, especially when many of the treatments were themselves offensive, called upon all of a nurse's energies and resources. . . . The situation extracted a heavy physical and emotional toll from nurses."73

Congregation of American Sisters

Just before the Spanish-American War, the Congregation of American Sisters, a very small order that never numbered more than twelve Native American women, broke with the Roman Catholic Church. Four Lakota nuns who remained in this group volunteered as contract nurses under the auspices of their priest, Rev. Francis Craft. Although the initial focus of the order was on teaching, Father Craft taught nursing skills to these women, and after offering their services to the War Department, he accompanied them as a hospital steward.

The Indian sisters in this group included: Susan Bordeaux (Rev. Mother Mary Anthony), assistant general; Josephine Two Bears (Rev. Sr. Mary Joseph); Ella Clarke (Rev. Sr. Mary Gertrude); and Anna B. Pleets (Rev. Mother Mary Bridget).74 Personal Data cards located for the first three women indicate they came from Fort Pierre, South Dakota. These sisters noted that they had received hospital training in the Hospital of American Sisters. They gave their ages as twenty-eight (for Clarke) and thirty-one (for Bordeaux and Two Bears) and stated they had "dark" coloring. A handwritten note on each card recommended them for duty, as they were "accustomed in missionary work in Indian camps to severe hardships, and privations, and exposure to heat and cold; and can therefore endure safely what most nurses cannot not endure. Accustomed also to attending sick in camps where the usual appliances and conveniences could not be had: and can therefore be of service in emergencies."75

The sisters signed contracts for duty as nurses at the going rate of thirty dollars a month, and all of them were sent on October 18, 1898, to Camp Cuba Libre, Jacksonville, Florida. One month later, they reported to the Division Hospital at Jacksonville. On December 13, 1898, they were transferred to the Second Division Hospital at Savannah, Georgia, and on December 22 they reported to the Second Division Hospital, Camp Columbia, Havana, Cuba. In February of 1899 they were again transferred, this time to the Military Hospital in Havana, Cuba. At the end of the month their contracts were annulled when their services were no longer required.

Mother Anthony, however, went on sick report on November 30, 1898, although she resumed her duties two weeks later, serving until the annulment of her contract as noted above. A notation on her card dated October 15, 1899, states: "Died, illness began with an attack of pneumonia while serving at Jacksonville. Died at Pinar del Rio, Cuba, and was buried in the military cemetery at Camp Egbert, Pinor del Rio."76

Sometime after the war, the three remaining sisters left the Congregation. Anna Pleets married Joe Dubray, and it appears that she worked as a midwife in later years. After her death in 1948, she was given a military funeral and was buried at St. Peter's Cemetery in Fort Yates, North Dakota.77 Ella Clark later married Joe Hodgkiss and spent her last years in the Old Soldiers Home in Hot Springs, South Dakota. Josephine Two Bears stayed in Cuba to run an orphanage until 1901. After returning to the United States, she became the wife of Joachim Hairychin but died during childbirth in 1909.78

Remarks on the Personal Data cards for the latter two women noted that they were "not strong" and had "poor health." They were given ratings of "4," which was the lowest ranking possible. A review of their assignment of duties from the Personal Data cards reveals that all four Indian sisters had been posted to five different hospitals in four months. This also demonstrates how sisters from the various religious communities moved from camp to camp as one site closed or an emergency need arose at another—a fact that attested to their devotion and commitment to the wounded. Is it any wonder that some contract nurses suffered from poor health by the end of their service? During the Civil War, "nurses sometimes broke under the strain and had to resign. . . . Practically all had to take periodic furloughs and at least one in ten suffered physical breakdowns while in the service."79 Nurses in the Spanish-American War were no less at risk.

Other Orders

Two nuns from the Protestant Sisters of St. Margaret and an undetermined number of sisters from the St. Barnabas Guild, an Episcopal organization, responded to the call for nurses.80 All these women, who signed government contracts, were accepted regardless of their religious belief if they completed the application blanks furnished by the DAR and filed them in the usual way. Once all these sisters had their qualifications individually certified, they were under contract and received pay exactly as the other nurses. Reports regarding their work were generally quite satisfactory, while Dr. McGee reported "some of the surgeons prefer them to the other nurses, and some prefer the others."81 While it is known that Sisters from other Catholic communities also served, they were not under contract.

Conclusion

By the time of the Spanish-American War, women began to make advances in nursing that were recognized by military officials, the medical corps, and the common soldier. No longer the untrained corps that entered the Civil War, nurses knew hospital and surgical procedures, and they demonstrated their skills in tent hospitals and operating rooms. Among the nurses who served were sisters from the various orders that have been described here. They provided valuable assistance not only in the camps but also on transports, trains, and in their own hospitals. In doing so, however, they often were overworked, became ill, and sometimes died after contracting the same fevers they had come to treat.

As had occurred in the Civil War, sister nurses continued to win the respect of the officers and surgeons with whom they worked, and they were often preferred to the other contract nurses. When the Spanish-American War ended, they returned home and resumed their normal tasks of nursing, teaching, and other charitable works. While much praise was given to them as a result of their work and dedication, the sisters viewed the hardships and experiences of camp life as an extension of their religious calling.

As one newspaper account noted:

It will have become generally known . . . that 224 sisters of different orders ministered to the sick and wounded, and that the services of many more were demanded by those who could best appreciate them. . . . The charity and devotedness of these angels of mercy constitute the silver lining to the war cloud.82

Mercedes Graf is a professor of psychology at Governors State University in Illinois. She is the author of several works about women and medicine, including Quarantine, a book about Typhoid Mary; A Woman of Honor: Dr. Mary E. Walker and the Civil War; "Women Nurses in the Spanish-American War," Minerva (Spring 2001), and "Women Physicians in the Spanish-American War," Army History (Fall 2002).

Notes

I would like to acknowledge the assistance of several people and institutions for archival materials and photos: My thanks in particular to Sr. Betty Ann McNeil and her assistant, Bonnie Weatherly, Archives & Mission Services, Daughters of Charity, St. Joseph's Provincial House, Emmitsburg, Maryland, for their generous assistance with research there. I am also grateful to Sr. Charline Sullivan and the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet, St. Louis Province, for making their archival materials available; the Sisters of Mercy in Chicago, Illinois, and Sr. Paula Diann Marlin, Mercy Center, Baltimore, Maryland; and the Sisters of the Holy Cross at Bertrand Hall, St. Mary's, Notre Dame, Indiana. Thanks also to the Pike County Historical Society; Brenda Finnicum for her personal comments on the Lakota Indian sisters; Donna Clark at Women in Military Service for America Memorial; Department of the Army, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; and Trevor K. Plante, military archivist, for his consultation and help at the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, DC.

1 The terms nun and sister are used interchangeably here, although the former term has been used to refer to cloistered women. While Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell helped to train a hundred women volunteers for the government and there were a few other women who had served in the Crimean War or managed to get some training on their own in select hospitals, by and large, volunteers had no formal training. Nursing schools began to spring up as a result of women's work in the Civil War. For more background on nursing, see Nutting and Dock, A History of Nursing.

2 Sr. Mary Denis Maher, To Bind Up the Wounds: Catholic Sister Nurses in the U.S. Civil War (1989), p. 101. For more information on Civil War nuns, see Ellen Ryan Jolly, Nuns of the Battlefield (1927). In the course of the war, at least 617 sisters from twelve different orders nursed both Union and Confederate soldiers.

3 Report of the Commission Appointed by the President to Investigate the Conduct of the War Department in the War with Spain (1900), vol. 1, p. 171, hereinafter referred to as "Conduct of the War with Spain." There are eight volumes.

4 From an untitled article probably meant to be a history of the Army Nurse Corps, unsigned (but apparently written by Dr. Anita Newcomb McGee), "Correspondence/Office Files of Dr. Anita Newcomb McGee, 1898–1936" (McGee Files), Entry 230, Records of the Office of the Surgeon General (Army), Record Group (RG) 112, National Archives Building (NAB), Washington, DC.

5 In an article, Dr. McGee pointed out that the DAR was not selected to do this work but volunteered. "Had the daughters not done this, there would have no such thing as an 'Army standard.'" See "Standard for Army Nurses," Trained Nurse and Hospital Review (TNHR) 33 (April 1899): 171.

6 Testimony of Dr. Anita Newcomb McGee, "Conduct of the War with Spain," vol. 1, p. 726. Dr. Nicholas Senn noted that nuns were on duty in nearly all of the national camps in Cuba and Puerto Rico as well as the United States. He stated that the number of sisters on duty as of September 24, 1898, was 232, and that "several of these brave sisters have gone to their final reward." See his book, Medico-Surgical Aspects of the Spanish-American War (1901), p. 324.

7 Testimony of Dr. Anita Newcomb McGee, "Conduct of the War with Spain," vol. 7, p. 3171.

8 In 1633 Vincent de Paul established the Company of the Daughters of Charity. Almost two centuries later, Elizabeth Seton, the American foundress of the Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph, adopted the rule of the French Daughters of Charity for her Emmitsburg, MD, community. In 1850 the Emmitsburg community united with the international community based in Paris. Government records, newspapers, and contemporary accounts, therefore, refer to them as "Sisters of Charity."

9 The number of sisters and their names are reported in "Memorandum for the Secretary of War, June 14, 1912," Historical Files of the Army Nurse Corps 1898–1947, Entry 103, box 3, RG 112, NAB.

10 Sr. Beatrice to George M. Sternberg, Surgeon General U.S.A., Apr. 23, 1898, Historical Files, Entry 103, box 3, RG 112, NAB. "Letter to Sr. Beatrice, Superior of Providence Hospital, Washington DC acknowledging receipt of letter offering the services of the Sisters," Apr. 28, 1898, from the Assistant Surgeon General, U.S. Army, in Military Hospitals, Official Correspondence, vol. I of six volumes (Military Hospitals: Official Correspondence), box 1, no. 3, Daughters of Charity Archives (DCA), St. Joseph's Provincial House, Emmitsburg, MD.

11 Some accounts note that there were about 189 Daughters of Charity; see, for example, Benjamin J. Blied, "Catholic Aspects of the Spanish American " Social Justice Review 39 (1947): 23–25. But Sr. Betty Ann McNeil, director of the archives at the Provincial Motherhouse in Emmitsburg, MD, indicated that there were 201 Daughters of Charity in the Spanish-American War from April 1898 through February 1899 (personal correspondence, Feb. 6, 2001).

12 "Standard for Army Nurses," p. 171.

13 "On Transports and in Camp: Experiences of a Band of Sisters of Charity," Sept. 24, 1898, unidentified newspaper clipping, vol. II (Service of the Sisters in Hospitals in the Spanish-American War), box 1, no. 36, DCA.

14 Locations are listed in vols. I–IV, Military Hospitals: Official Correspondence, DCA.

15 "Telegram to Mother Marianna," July 15, 1898, vol. I, Military Hospitals: Official Correspondence, box 1, no. 4, DCA.

16 The names of the sisters were: Magdalen Kelleher, Cecelia Beck, Chrysostom Moynahan, Maria Conway, and Victorine Salazar. This is listed in a handwritten note at the bottom of the telegram noted in the preceding citation.

17 "Letter of Sr. Salazar to the Sister Assistant," Aug. 29, 1898, vol. II, Military Hospitals: Official Correspondence, box 1, no. 20, DCA.

18 Ibid. Three of the Spanish POWs died while hospitalized. They are buried in the hospital cemetery, and each Memorial Day their graves are marked with Spanish flags. Capt. T. H. Conaway, Jr., notes that this was a practice he started when he was stationed at the naval hospital as a junior officer. Quoted in his paper, "Spanish-American War," a copy of which resides in box 5, DCA.

19 "Letter of Dr. Cleborne, Medical Director, U.S. Navy, Norfolk, Virginia," Sept. 7, 1898, box 4, no. 59a & b, DCA.

20 "Letter from the Surgeon General of the Navy," Sept. 12, 1898, vol. II, Military Hospitals: Official Correspondence, no. 25, DCA.

21 Names of sisters serving at Montauk can be found in Historical Files, Entry 103, box 3, RG 112, NAB.

22 Ibid.

23 "Conduct of the War with Spain," vol. 8, pp. 217–218.

24 "Letter to Sister Josephine," Aug. 25, 1898, box 1, vol. II, no. 49, DCA. Also see Philip A. Kalisch, "Heroines of '98: Female Army Nurses in the Spanish-American War," Nursing Research 24 (1975): 411–429. He details the nurses' devotion to duty, contributions, and successes as well as their trials, tribulations, and sufferings.

25 "Letter from Sr. Adelaide," Aug. 31, 1898, vol. II, Military Hospitals: Official Correspondence, box 1, no. 50, DCA.

26 "Health Coming, Men of the 9th Improve with a Day of Rest," unidentified newspaper article, ibid., no. 65.

27 "Letter from Ellen Loraine Dorsey," Sept. 4, 1898, ibid., no. 69. Dorsey was responsible for recruiting the Catholic nursing sisters for wartime service.

28 "Letter to the Mother Superior," Sept. 19, 1898, ibid., no. 74.

29 See Personal Data (PD) cards of Spanish-American War Contract Nurses, 1898–1917, Entry 149, box 6, RG 112, NAB. The card for Agnes Sweeney notes she was age thirty-six when she volunteered. Attached to the card is a newspaper account that notes her death.

30 See PD card for Anne Larkin, ibid., box 4. She was age thirty-five when she volunteered, and her date of death is listed as November 4, 1898.

31 See PD card for Caroline Wolf, ibid., box 6. It notes that she was twenty-five years old when she was first sent to Chickamauga Park and then on to the Third Division Hospital, Camp Hamilton, Lexington, Kentucky. Also see "First Nun Victim of Camp Fever: Sister Caroline Contracted Typhoid while Nursing Soldiers at Chickamauga and Knoxville," unidentified newspaper clipping, vol. III (Hospital Service in the Spanish-American War contd.), no. 28, DCA. According to the rules of the order, she could not be professed until she had been a member for five years; when it became almost certain she would die, she was allowed to make her final vows.

32 The death of Burke is noted in "D.A.R. Nurses Who died in Army Service," Historical Files, Entry 103, RG 112, NAB. Sixteen names are listed here for women contract nurses and nuns. Her father wrote a letter to Mother Mariana saying that her death "was a most severe blow to us. So great, in fact, was the shock that it took us some time to fully realize the real purport of the news." (She was only twenty-three years of age.) See "Letter of Miguel F. Burke," Jan. 14, 1899, vol. V (Letters Received), no. 35, DCA.

33 "Sisters in Army Hospitals: Work of Mercy Which they Performed at Camp Wikoff," unidentifed newspaper clipping, vol. II, box 1, no. 84, DCA.

34 The names of the twelve sisters are listed in a brief summary, "Santiago," vol. II, box 1, no. 26, DCA. Five sailed from New York on the Yale, and seven boarded the Yucatan.

35 "Sr. Mary Carroll's Letter to the Mother Superior," Aug. 26, 1898, vol. II, box 1, no. 32, DCA.

36 "Letter of Sister Julia Kelly," Aug. 27, 1898, vol. III, box 2, no. 4, DCA.

37 "Sternberg Comparison with World War," unsigned memoir in McGee Files, Entry 230, box 1, RG 112, NAB.

38 Telegram, Chief Surgeon Hartsuff to the Surgeon-General, United States Army, Apr. 25, 1898, in "Conduct of the War with Spain," vol. 8, p. 185.

39 Maud Cromelien, "Red Cross Work at Chickamauga Park," TNHR 23 (September 1899): 128–129.

40 "Scenes in Camp Thomas, Chickamauga Park," letter dated Sept. 2, 1898, vol. III, no. 7, DCA.

41 "Letter of Sr. Mary Stella Boyle," Sept. 3, 1898, vol. III, box 2, no. 10, DCA.

42 "Letter of Sister Blanche," n.d., vol. III, box 2, no. 11, DCA.

43 "Letter to the Mother Superior," Sept. 23, 1898, vol. III, box 2, no. 23, DCA.

44 "Letter of L. Brechemin, Major & Surg. U.S.A.," Sept. 27, 1898, vol. III, box 2, no. 25, DCA.

45 See "Camp Alger, Virginia," vol. III, box 2, no. 30, DCA. This summary notes that the officer was hostile to anything Catholic. "He abruptly informed the Sisters that they were not wanted . . . a reluctant consent was given that ten might remain."

46 For an account of their work during the Civil War, see Jolly, Nuns of the Battlefield.

47 "Letter to the Reverend Mother Agatha from Camp Hamilton," Oct. 12, 1898, Sisters of St. Joseph Carondelet Archives (SSJC), St. Louis, MO.

48 "Letter from Sr. Liguori McNamara at Camp Hamilton," Oct. 15, 1898, SSJC Archives.

49 Office of the Surgeon General, Personal Data (PD) cards of Spanish-American War Contract Nurses, 1898–1917, Entry 149, RG 112, NAB. Cards are arranged alphabetically and contained in six boxes. Every card contains a questionnaire filled in by the applicant that asks for such information as name and address, name of nursing school, hospital experience, age, birthplace, physical characteristics (skin color and health—race is not listed), and marital status. Cards also contain places of service and grades for performance in terms of health and ability. In postwar years other comments were appended that gave information regarding medals awarded, burial, etc.

See Lists of Sisters in Historical Files, Entry 103, box 3, RG 112, NAB. The sisters came from four provinces: St. Louis and Kansas City, Missouri, and St. Paul and Minneapolis, Minnesota. Nuns from St. Louis (St. Joseph Convent) included: Sr. M. Rudolph Meyers, Sr. M. Bonaventure Nealon, and Sr. M. Raymond Ward. From Kansas City (St. Joseph Hospital): Sr. M. Irmina Dougherty, Sr. M. Delphine Dillon, and Sr. M. Liguori McNamara. From St. Paul, Minnesota (St. Joseph's Hospital): Sr. M. Blandina Geary, Sr. M. Florentia Downs, and Sr. M. Julitta Carroll. From Minneapolis, Minnesota (St. Mary's Hospital): Sr. M. Thecla Reid, Sr. M. Aloise O'Dowd.

50 PD card of McNamara, Entry 149, box 4, RG 112, NAB.

51 From a summary of the sisters' service in "The Spanish-American War," SSJC Archives.

52 "Letter from Sr. Liguori McNamara at Camp Hamilton," Oct. 18, 1898, SSJC Archives.

53 Ibid.

54 "Letter from Sr. Liguori at Camp Hamilton," Oct. 22, 1898, SSJC Archives.

55 "Letter from Sr. Liguori at Camp Gilman, Americus," Dec. 21, 1898, SSJC Archives,

56 "Letter from Sr. Liguori at Matanzas, Cuba," Feb. 25, 1898, SSJC Archives. But Civil War nuns had their problem with fleas too as reported by Sr. Camilla O'Keefe, Daughter of Charity, when nursing at Gettysburg: "The sisters also brought plenty of the vermin along in their clothes. I shudder to think of this part of the sister's sufferings while they were serving in the military hospitals, especially in the field tents in Gettysburg;" in Sister O'Keefe's narrative, unpublished, DCA.

57 "Letter from Sr. Liguori at Matanzas, Cuba," Mar. 9, 1899, SSJC Archives.

58 "Letter from Sr. Liguori," Apr. 1, 1899, SSJC Archives.

59 See "Summary of Sisters' Service in The Spanish-American War," SSJC Archives. Christopher J. Kauffman, A Religious History of Catholic Health Care in the United States (1995), p. 165, noted that their service in the war had "so depleted the nursing staff at St. Joseph's Hospital in Kansas City that the personnel crisis led to the foundation of the hospital's nursing school" in 1901.

60 The service of the Sisters of Mercy is discussed by Sr. M. Lucille McGee Middleton, RSM, in "Mercy on the Battlefields," typescript copy dated 1980, Mercy Archives, Chicago, IL. Also see, Suzy Farren, A Call to Care: The Women Who Built Catholic Healthcare in America (out of print). She provided excerpts from Sr. Nolasco's diary.

61 See Historical Files of the Army Nurse Corps 1898–1947, Entry 103, box 3, RG 112, NAB. Fourteen Sisters of Mercy were listed, but Sr. Flanagan's name was underlined with a notation "died" beside it. The others (using surnames) were: Srs. Doyle, Fenwick, Klinefelter, Leonard, McColm, Middleton, Mullin, O'Kane, Prendergast, Smith, Stone, Weld, and Davis.

62 "The Work of Catholic Sisters," Catholic Mirror (Baltimore), Feb. 4, 1899. Sr. Mary Elizabeth Flanagan's PD card notes that she went on sick report September 30, 1898, with typhoid fever and died November 1 in the hospital. See her card, Entry 149, box 2, RG 112, NAB. Also see Sr. Mary Eulalia Herron, Sisters of Mercy in the United States, 1843–1928 (1929).

63 See Lists of Sisters in Historical Files, Entry 103, box 3, RG 112, NAB.

64 Barbara Mann Wall, "Courage to Care: The Sisters of the Holy Cross in the Spanish-American War," Nursing History Review 3 (1995): 55–77.

65 PD cards also indicate surnames: Sarah Baden (Sr. Galasia), Ellen Casey (Sr. Joachim), Caroline Conway (Sr. Genevieve), and Margaret Clifford (Sr. Lydia) who served in a military hospital during the Civil War, box 1; Ellen McSweeny (Sr. Camillas) and Mary McCabe (Sr. Cornelius), box 4; Adelaide Reid (Sr. Valentina), box 5; Mary Stack (Sr. Florentia), Entry 149, box 6, RG 112, NAB. Born in Ireland: Clifford, McCabe, and McSweeney. In some cases "Mary" or "M." was inserted in front of the sister's name. No cards for: Agnes Gahagan (Sr. Cordella), Margaret O'Connor (Sr. Biniti), Ellen Horan (Sr. Philip), and Miss Nowlan (Sr. Emerentiana).

66 Wall, "Courage to Care," p. 69.

67 The Cuban Sisters are listed as: Srs. Angela (Diaz), Simona (Galarza), Josefa (Gil), Mary Josefa (Guarnero), Clara (Larinago), Filomena (Morros), Margarita (O'Keefe), Juliana (Olleta), Angela (Quesada), Victoria (Saez), Isidora (Frigo), and Mercedes (Civit). In Historical Files, Entry 103, box 3, RG 112, NAB.

68 PD Cards: Sr. Galarza, box 2; Sr. Gil, box 2; Sr. Civit, box 1, Entry 149, RG 112, NAB.

69 John W. Ross, M.D., "Lessons Drawn from Practical Professional Experience with Trained Women Nurses in Military Service," Journal of the Association of Military Surgeons of the United States (November 1902): 274.

70 Ibid., p. 275.

71 An interesting fact on Sr. Civit's PD card was that she stated she was six feet in height, which was tall for a woman of that period. See her PD card, box 1, Entry 149, RG 112, NAB. Clara Louise Maass, a former SAW contract nurse also worked here and volunteered to be bitten by an infected mosquito, from which she died of yellow fever. See J. T. Cunningham, Clara Maass: A Nurse, a Hospital, a Spirit (1976). Also see Maass' PD card, box 4, which notes she died August 24, 1901. She was the only American woman and the only nurse to have participated in such experiments.

72 Turner Memoir, McGee Files, Entry 230, box 1, RG 112, NAB.

73 Quote of Eleanor Krohn Herrmann, who details yellow fever nursing at Las Animas. In "Clara Louise Maass: Heroine or Martyr of Public Health?" Public Health Nursing 2 (1985): 53–54.

74 List of Indian sisters in the Historical Files, Entry 103, box 3, RG 112, NAB.

75 See PD Cards for: Ellen Clarke (Rev. Sister J. Gertrude), box 1; Susan Bordeaux (Rev. Mother M. Anthony), box 1; Josephine Two Bears (Rev. Sister J. Joseph), box 6, Entry 149, RG 112, NAB.

76 The PD card for Rev. Mother M. Anthony indicates that she was born on September 18, 1867, in Beaver Creek, NE; Entry 149, box 1, RG 112, NAB. Brenda Finnicum notes that she "has been reported to be the granddaughter of Chief Spotted Tail and the grandniece of Chief Red Cloud." See Finnicum, "The First Indian Army Nurses," Indian Country Today, Jan. 3, 2001.

77 The Registry of the Women in Military Service for America (WIMSA) reported that the sister's grandson, Harry Dubray, listed her name and provided information on December 12, 1968. Personal communication with Donna Clark, registrar at WIMSA.

78 Finnicum, "The First Indian Army Nurses."

79 Mary Elizabeth Massey, Women in the Civil War (1994; orig. publ. as Bonnet Brigades [1966]).

80 "Conduct of the War with Spain," vol. 7, p. 3171.

81 Ibid. A similar situation existed in the Civil War when Dorothea L. Dix was disappointed to see surgeons dismissing her government nurses and hiring nuns in their places. The sisters were highly commended by the surgeons who worked with them, "chiefly because they had been trained to obedience. Soldier patients liked them, and scornful but envious Protestant nurses had to concede them the virtues of 'order and discipline,' though sometimes questioning their 'neatness' and intelligence." Quoted in Adams, Doctors in Blue: The Medical History of the Union Army in the Civil War (1952), p. 183.

82 "Nursing the Sick," undated article from an unidentified newspaper, vol. II, no. 36, DCA.