The Nixon White House Tapes

The Decision to Record Presidential Conversations

Summer 1988, Vol. 30, No. 2

By H. R. Haldeman

© 1988 by H. R. Haldeman

About sixty hours of Richard Nixon's White House tapes will be opened by the National Archives sometime in 1989. This is the first segment of the tapes to be opened, other than the twelve and a half hours of recordings that were entered into evidence in U.S. v. Connally and U.S. v. Mitchell, et al.—the so-called Milk Fund and Watergate trials. This new sixty-hour segment is also Watergate related: It comprises those recordings that were subpoenaed by the Watergate Special Prosecution Force but were not entered into evidence. These Watergate-related recordings are a tiny fraction of the whole body of the White House tapes—about seventy hours out of approximately four thousand hours. But the opening of the sixty-hour segment has an importance beyond Watergate. It is the first of what in the next several years will be a series of openings. The time has finally come, almost fifteen years after the end of the Nixon administration, when one may reasonably look forward to hearing at least the unclassified and otherwise un-restrictable portions of the White House tapes. The National Archives' processing of the tapes is virtually complete, and the agency is nearly ready to go forward with a schedule of phased openings. The opening of the entire four thousand hours of the White House tapes is—at least in scholarship's geological sense of time—just around the corner.

I want to use the proximity of this important occasion to put forward, in a fuller way than I did ten years ago in The Ends of Power, my recollection of the events surrounding President Nixon's decision to install the White House taping system. The Ends of Power was necessarily focused on Watergate, and it was unfortunately sensational in many instances where I would have preferred it to be more reasoned and thorough. This essay is for me the first step in what I anticipate will be a much larger project of my recollections of and reflections on the men and events that made up the presidency of Richard Nixon.

Sometime during the transition between the Johnson and Nixon administrations—during the frantic seventy-five days between election day and inauguration day, when the president-elect and his raw and aspiring staff struggled to piece together the personnel and policy framework of a new administration—Nixon learned that Lyndon Johnson had in the White House's West Wing a taping system that permitted him to record both meetings and telephone conversations. I cannot recall whether Nixon learned of the system from Johnson himself or from J. Edgar Hoover. When Nixon and I came to the White House on Inauguration Day, 1969, we found what we believed to be Johnson's taping equipment in what was to be my first office, the small room just to the west of the Oval Office. It was hidden in the upper part of a closet just next to the fireplace. The electronic gear was really quite imposing to two such technical tyros as Nixon and me, and we naturally supposed that quite a lot of the business of the Johnson White House had been tape recorded.

Nixon abhorred the idea of taping the president's meetings and telephone conversations. He ordered the equipment removed immediately when he came to the White House, as he did Johnson's triple television monitor system and his ticker-tape machine. The new president shared none of the outgoing one's love of gadgetry. All of Johnson's machines were quickly removed. Nixon's White House, as these actions taken immediately after our arrival seemed to assure, was to be free of garish electronics, and there was to be no surreptitious recording of meetings and conversations.

Of course, Nixon's presidency was ultimately brought down in large measure by tape recordings of his meetings and telephone conversations. He changed his mind about tape recordings, but he did so hesitantly, over a considerable period of time, and as a consequence of a sequence of failed attempts to solve a problem that seemed to leave no alternative to recommencing taping in the White House.

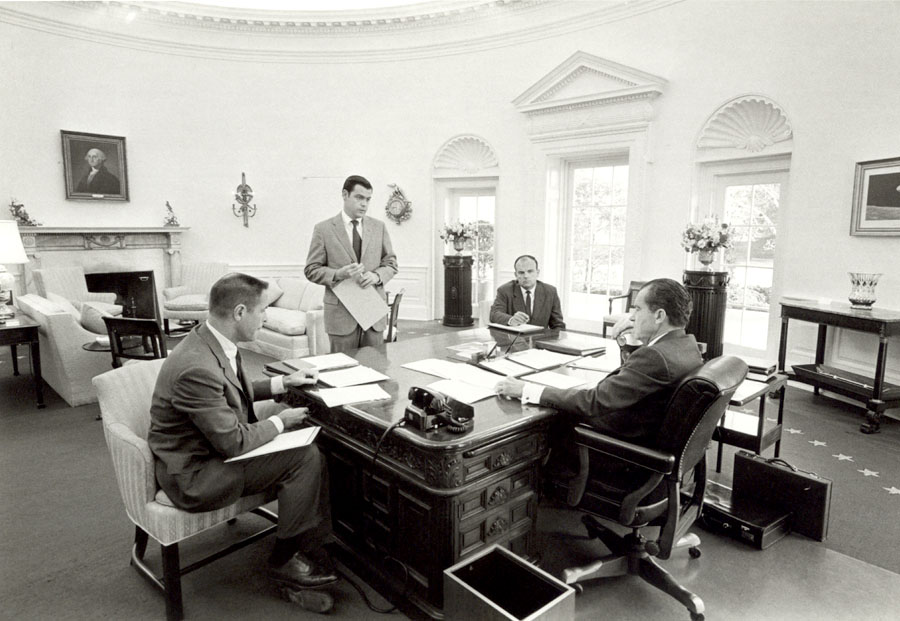

The problem was that people who met with the president did not always report accurately or completely what was said and decided privately. Sometimes the error was honest; Nixon often knew much more about a subject than the person he was meeting with, and misunderstanding sometimes resulted from this. More often, though, the inaccurate reports had more self-serving motives. Contact with the president presents many temptations to people and brings out many things in their personalities that might never have appeared had they not been flattered with Oval Office meetings. Johnson had warned Nixon and me about what would happen. "Everybody in this town," he said, "will call somebody else and say, 'the President wants this and the President wants that. — We found this was true. And the people who claimed to know what the president wanted were often believed—because they had just this morning, or just yesterday, stepped out of a meeting in the Oval Office. Sometimes the misreporting of fact had a bad intent, sometimes it represented a willful manufacture of false knowledge in order to gain some end.

There was a second reason to want an accurate account of what occurred during presidential meetings. Nixon liked the idea of meeting with foreign leaders without his own interpreter; he did not always do this, but frequently he did. For example, during meetings with Soviet leaders, he often relied on the remarkable Viktor Sukhodrev for translations; he similarly relied on the Chinese interpreter during many of his meetings in the People's Republic of China in 1972. He felt that this going bare, as it were, into meetings would lend them a sense of intimacy and confidence that might further the diplomatic exchange. This was, in my opinion, a wonderfully effective concept, but it presented an obvious problem. How was one to be sure of what was said and agreed in such meetings? How could one be sure the translations were accurate, and that the president and the foreign leader knew what one another was talking about? Nixon often took with him into such meetings some staff person—not a translator, but someone perhaps from the National Security Council who properly belonged in the meeting—who knew the other language and could assure him after the meeting was over that the translation had been accurate. But this practice was only sometimes followed, and it was, in any case, an inadequate expedient.

A third reason why Nixon wanted an accurate record of his presidency was for his eventual use in preparing his memoirs and other writing projects that he might undertake after his term of office was over.

Something had to be done, both Nixon and I agreed, to ensure that we possessed an accurate record of what was said in meetings. We tried a series of experiments during 1969 and 1970. We tried for a time including a note-taker in meetings. But this experiment ended very quickly. Nixon was opposed to it from the beginning, and trying it only confirmed him in his dislike. He had had note-takers forced on him by the State Department during his foreign travels as vice president. He felt these scribbling intruders inhibited discussion; he did not like them as vice president and he would not have them as president. A second experiment, which I think General Andrew J. Goodpaster, who had often served as note-taker for President Eisenhower, suggested to us, was to either have someone debrief the president and take notes after a meeting or have the president make the notes himself, either by hand or through dictation. We made a feint at trying this, but it was impossible. Nixon was simply too busy to make his own notes. A third experiment was to establish just outside the Oval Office a debriefing note-taker who would catch visitors as they left their meetings and record, from the visitors' testimony, what had happened. This was an impossible scheme too. It was very awkward, to say the least, and at best it got on record only the visitors' views of the meetings' contents.

All of these experiments failed, and as we rejected them one after the other, Nixon would frequently complain that, in addition to the other flaws of all these recording methods, none of them captured the human intangibles of the meetings, the subtle nuances of expression and tone of voice that were often of substantive importance and always of historical significance. These intangibles were being lost, and that concerned him. We thought that we could at least get these on record, if not a full account of the meeting, by having selected White House staff people sit in on meetings and later prepare memorandums describing the feeling and tone of what happened. I did some of this work myself, as did John Ehrlichman, Henry Kissinger, and many others of the staff. The staff secretary's office worked determinedly to extract these color memorandums from sometimes unwilling and delinquent staff. This experiment had some limited success, and these color memorandums were prepared for selected meetings through all of the Nixon presidency.

Nixon and I had an idea that might have transformed this color memorandums method into something capable of providing a more thorough record of his meetings. We thought of the perfect person who could prepare memorandums that would record, not only the intangibles of feeling and tone, but everything, possibly every word. This was General Vernon Walters, who later became deputy director of the Central Intelligence Agency and the United States Ambassador to the United Nations. He has a phenomenal memory. I was once present at a dinner at which German Chancellor Kurt Kiesinger gave a speech, ten minutes or so in length, which was, at its conclusion, badly translated into English. The other Germans present began to thump the table, as if to say, "That's not correct." At that point General Walters rose from his seat and gave a perfect translation of what the chancellor had said, from memory, without help. This was certainly the perfect man to be our note-taker. I had the assignment of offering him the job. I very naively called him in and made the offer, adding that his president needed him. He drew himself up and inflated himself to full general-size height and breadth, inserted his array of medals right in front of my nose, and said, in effect, "I am a general in the United States Army, I am a commander of troops. I am not a secretary to anybody." This was one of those times when Haldeman withdrew quietly from the battle. Nixon and I had lost our perfect note-taker.

Two years into his presidency, Nixon had still not found a satisfactory way of getting a full account of what was said and decided in his meetings. Many experiments had been tried, and just as many had been discarded. I believe that it was Lyndon Johnson who finally solved our problem for us, not with a new idea, by any means, but with a decisive nudge toward an old idea. As a former president, Johnson could offer Nixon advice on some subjects with an authority no one else could match. Somehow, probably through some friend of Nixon's who had been conversing with Johnson on how best to set up a Nixon Library, word got back to Nixon, probably in late 1970 or early 1971, that Johnson's view was that he was foolish not to be keeping a record of what was going on, and that a good record was essential to the preparation of a former president's memoirs. I don't know for certain that such advice from the former president got to Nixon, but I believe it did.

In any event, Nixon suddenly was receptive to the idea of taping his meetings. As I recall, he and I discussed the possibility of installing a taping system on several occasions during the first few weeks of 1971. Finally, still reluctantly, Nixon agreed that taping was the best way to achieve an accurate record of his meetings. He suggested we might install the same kind of switch- or button-operated machine that Johnson had used; that would allow him to turn the system on or off as he thought best. I responded, "Mr. President, you'll never remember to turn it on except when you don't want it, and when you do want it you're always going to be shouting—afterwards, when it's too late—that no one turned it on." I added, silently, in my own thoughts, that this president was far too inept with machinery ever to make a success of a switch system. I suggested an alternative that I knew very little about—a voice-activated system. He was interested. I explained that I thought it was possible that a recording system could turn itself on or off according to the presence or absence of sound in the room. Nixon told me to look into acquiring such a system.

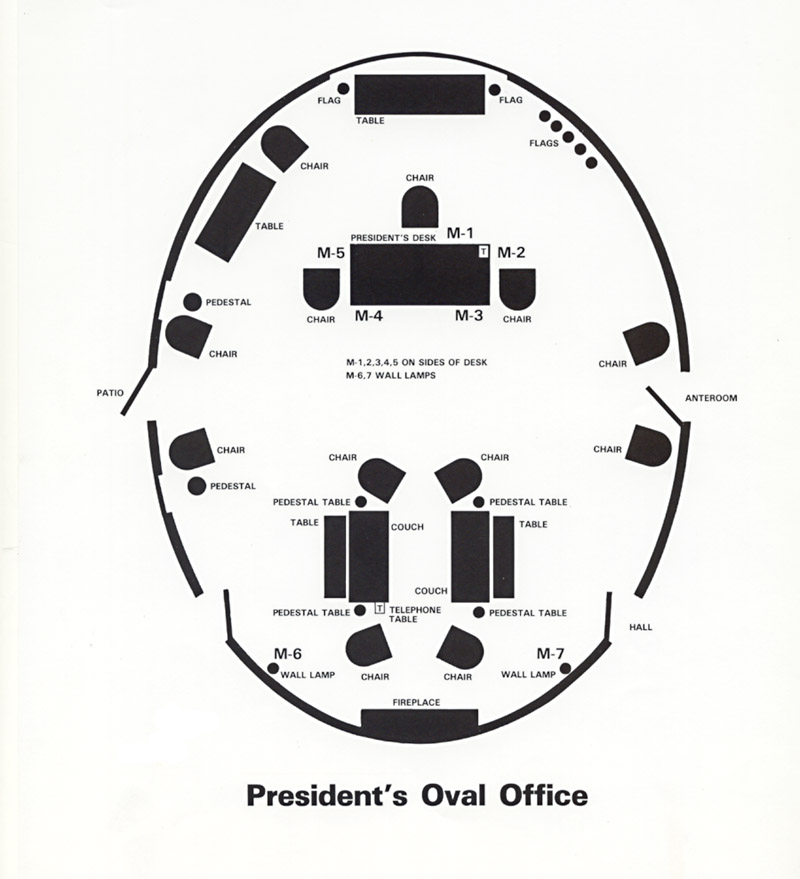

My next step, as I remember, was to instruct my assistant Lawrence M. Higby to see to the acquisition and installation of the necessary equipment. He in turn instructed another of my assistants, Alexander P. Butterfield, to work with the Secret Service on this assignment. I under stand that initially only the Oval Office and the Cabinet Room were included in the system. The Cabinet Room was the only location ever to be included in the taping system that was not sound activated; a control mechanism in Butterfield's office had to be switched on in order to activate the machinery. The Oval Office machinery—and this was true of all the other White House taping locations—was activated by the Executive Protective Service's First Family Locator system; whenever an officer notified the system that the president was now in the Oval Office, the appropriate light came on in boxes scattered around the West Wing, and the taping machinery switched on. It was poised and ready to begin taping whenever any sounds occurred.

The taping system began operating in the Oval Office and the Cabinet Room on February 16, 1971. On April 6, the president's office in the Old Executive Office Building and his telephones in both this office and the Oval Office, and the telephone in the Lincoln Sitting Room in the Residence, were added to the system. Over a year later, on May 18, 1972, the president's office and two telephones in Aspen Lodge at Camp David were also added—on Butterfield's own authority and representing his judgment that in adding Camp David to the system, he was merely doing something he should have done much earlier in response to Nixon's initial order to install a taping system. The Camp David installation completed the system. The Aspen Lodge office was taken off the system in March 1973. On April 9, 1973, Nixon told me to remove the rest of the taping system, but later that same day he changed his mind—he wanted to retain the system, but he wanted it converted to a switch basis. For reasons I cannot remember, Nixon's order was not carried out. The sound-activated system remained in place in the president's offices until it was finally shut down on July 18,1973, two days after Alexander Butterfield told the Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities—the so-called Ervin Committee—of its existence.

From the moment the taping system was first seriously discussed, Nixon insisted that the recordings were to be for his use, and possibly mine, only. No one else was to listen to them; as few people as possible were to know of their existence—which meant, practically, besides Nixon and me, Lawrence Higby, Alexander Butterfield, and a few Secret Service technicians.

Later, Stephen B. Bull, who replaced Butterfield in February 1973, would have known too. No one else on the White House staff or anywhere else—not Kissinger, Ehrlichman, Haig, Dean, Colson, Mitchell, or any of the other people made famous during the Nixon years—knew of the existence of the taping system until Ehrlichman learned of it during Watergate discussions in March 1973.

It is amazing to me when I think back to the first days, weeks, and months of the taping system's existence how quickly I forgot about it. For a short time, I worried that it might not be working, and I dispatched someone to test the machinery. But the worry quickly passed, as did any awareness at all that Nixon's conversations—my conversations, often—were being taped. I think Nixon lost his awareness of the system even more quickly than I did. Our conversations went forward as the press of business required. I sometimes ask myself if I would have said some things differently if I had consciously considered the fact that my words were being taped. I am not sure what answer to give myself. The obvious answer is, "Yes, of course." But my confidence that the tapes were never going to be heard by anyone except Nixon and myself was so great that I really do suspect I would have pushed any incipient worry about disclosure aside and spoken just as I did.

At one point—early in 1972, after the system had been in place for about a year—Alexander Butterfield came to see me and said our taping system had made quite a pile of full reels; he assumed, he said, that I wanted them transcribed. I took this rather thoughtless suggestion to Nixon. He would not have it, and restated his insistence that the tapes should remain absolutely private. I argued briefly for transcribing the tapes, but slowly gave the matter up. I realize now how naive my argument was. Not only would transcribing have breached the security of the tapes, it would have required an army of transcribers beyond my imagining; I know now that transcribing is possibly the most labor intensive work on earth. We would have had to start up a new agency to get the job done. And the product of all this work, as I learned during the Watergate trial, would have been worse than useless. I have become convinced that there can be no such thing as a completely accurate transcript, at least not of Nixon's White House tapes.

To the best of my knowledge, Nixon never used the White House tapes for any of the purposes he had had in mind when he ordered the system installed until he ordered me in mid-April 1973 to listen to the recording of his March 21, 1973, conversation with John Dean during which Dean had described at length the problems that Watergate had created for the presidency. He wanted to know precisely what he had said during that troubling conversation. On one other occasion, Nixon at least considered using the taping system for one of its designed ends. In November 1972, Henry Kissinger gave an interview to Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci in which he seemed to distance himself from the president's position on the then acutely sensitive Vietnam peace negotiations. Nixon was gravely upset by this. He told me to warn Kissinger that his conversations with the president had all been recorded. I am virtually certain I never gave Kissinger this message. I chose to consider what Nixon said to me more as a flare of anger than as considered instruction, and I probably told Kissinger simply to be more careful about what he said during interviews.

I attended a conference on the Nixon presidency recently, at Hofstra University. One of the sessions was on the Nixon papers and tapes. The lead speaker was James Hastings, the head of the office in the National Archives that has custody of Nixon's White House tapes. When he described the tapes—their poor sound quality, their four thousand-hour running time, the twenty-seven thousand-page finding aid that the archivists have prepared in order to describe them for researchers—I was surprised to see a few historians in the audience scowling and waving their hands, as if to say, "No, we don't want them—it's too much work." I understand their fear and trembling before so immense a task of research as the White House tapes present, but I am certain they will feel differently after a little time for reflection has passed. The historians' digestion of the White House tapes will be long, slow, and tedious, but the tapes are an incomparable source, and the historiography of the Nixon administration will eventually be much the richer as a result of Richard Nixon's decision to tape-record his meetings and telephone conversations. Nixon was not thinking of historians when he made this decision, but they will be its ultimate beneficiaries.

Mr. Haldeman wishes to acknowledge the assistance that Raymond H. Geselbracht, an archivist at the Harry S. Truman Library, gave him in the preparation of this paper, which is based primarily on an oral history interview which he conducted with Mr. Geselbracht and Frederick J. Graboske on August 13, 1987.