Photographs from the Dorothy Davis Case

In April 1951, the students at Robert Russa Moton High School in Prince Edward County, VA, went on strike. Although their protest was intended to persuade their local school board to build them a better school, it actually led to a landmark civil rights case that marked the end of legal segregation in the nation's public schools. This was one of five cases that the Supreme Court heard collectively and consolidated under Brown v. Board of Education. Read more...

Primary Sources

Links go to DocsTeach, the online tool for teaching with documents from the National Archives.

Find many more photographs from Moton, Farmville, and Worsham high schools – that were entered by both the plaintiffs and the defendants – on DocsTeach.

Teaching Activities

The "Rights in America" page on DocsTeach includes primary sources and document-based teaching activities related to how individuals and groups have asserted their rights as Americans. It includes topics such as segregation, racism, citizenship, women's independence, immigration, and more.

Additional Background Information

Arguments presented and decisions rendered in court cases often illuminate, open, and sometimes close frontiers in social history. For example, the arguments presented in school desegregation cases of the early 1950s illustrate how the "separate but equal" doctrine presented in the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896 virtually closed the civil rights frontier for nearly 60 years. Conversely, the decisions rendered in the desegregation cases opened up that frontier and encouraged the expansion of the civil rights movement in the latter half of the 20th century.

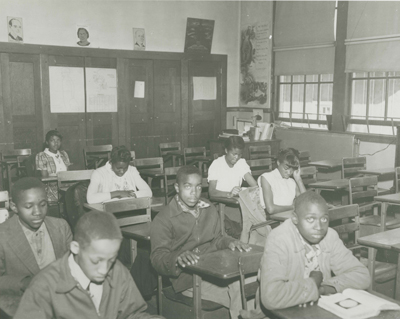

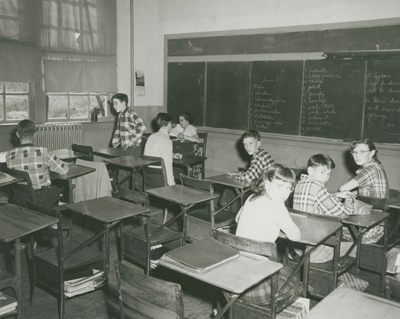

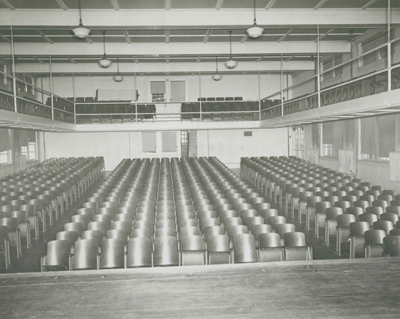

Moton High School in Prince Edward County, Virginia, was typical of the all-Black schools in the central Virginia county. It was built in 1939 to hold half as many students as it did by the early 1950s. Its teachers were paid substantially less than teachers at the all-white high schools. It had no gymnasium, cafeteria, or auditorium with fixed seats like the nearby Farmville or Worsham high schools, which were for white students.

Repeated attempts by Moton's principal and the parent-teacher association (PTA) to convince the school board to erect a new Black high school were fruitless. So, in the spring of 1951, the students, led by 16 year-old Barbara Johns, took matters into their own hands. They went on strike and asked for help from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), specifically the NAACP's special counsel for the Southeastern region of the United States.

The NAACP lawyers told the striking students that the only way the organization could commit to getting involved in the students' cause was to sue for the end of segregation itself – a huge step beyond the goal of a new school building. After thinking it over very carefully and gathering the support of their parents, the students agreed to challenge segregation directly. On May 23, 1951, a NAACP lawyer, on behalf of 117 Moton students and their parents, filed suit in the federal district court in Richmond. The first plaintiff listed was Dorothy E. Davis, a 14-year old ninth grader; the case was titled Dorothy E. Davis, et al. versus County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia. It asked that the state law requiring segregated schools in Virginia be struck down.

Both the plaintiffs (the students) and the defendants (the Prince Edward County school district) entered several photographs as exhibits in the case. The plaintiffs wanted to demonstrate unequal facilities. The defendants were trying to show that they were providing equal facilities in both Black and white schools.

In the spring of 1952, a three-judge U.S. District Court decided in favor of the school board and upheld segregation. On appeal, the case made it to the Supreme Court of the United States and was decided along with three other school segregation cases from South Carolina, Delaware, and Kansas, in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka.

The Brown decision marked the end of the "separate but equal" precedent set nearly 60 years earlier in Plessy v. Ferguson. The court stated that "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal," and that school segregation violated the Fourteenth Amendment. (The Supreme Court actually heard five cases together, and consolidated them into Brown v. Board of Education. They issued a separate ruling for one of the cases, Bolling v. Sharpe, however, because it was filed in Washington, D.C. — the 14th Amendment only applies to states and is not applicable in the District of Columbia.)

The Commonwealth of Virginia, and Prince Edward County in particular, resisted the Supreme Court's decision. The county closed its public schools from 1959 to 1964 to avoid desegregation.

This text was adapted from the article: Potter, Lee Ann. “Frontiers in Civil Rights: Dorothy E. Davis, et al. versus County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia.” National History Day Teachers' Guide: Frontiers in History: People Places, Ideas (2001); 71-75.

Materials created by the National Archives and Records Administration are in the public domain.

Materials created by the National Archives and Records Administration are in the public domain.