The Amistad Case

In February of 1839, Portuguese slave hunters abducted a large group of Africans from Sierra Leone and shipped them to Havana, Cuba, a center for the slave trade. This abduction violated all of the treaties then in existence. Two Spanish plantation owners, Pedro Montes and Jose Ruiz, purchased 53 Africans and put them aboard the Cuban schooner Amistad to ship them to a Caribbean plantation. On July 1, 1839, the Africans seized the ship, killed the captain and the cook, and ordered Montes and Ruiz to sail to Africa. Read More...

Related Primary Sources

Teaching Activities

U.S. v. Amistad: A Case of Jurisdiction on DocsTeach asks students to analyze specified passages from the Supreme Court's decision in United States v. Libellants of Schooner Amistad to explore the concept of jurisdiction and how a case travels through the Federal court system. Students will also interpret the Supreme Court's role in the judicial branch by connecting the document back to the United States Constitution, and ultimately decide if they agree with the Supreme Court's ruling in the case.

Additional Background Information

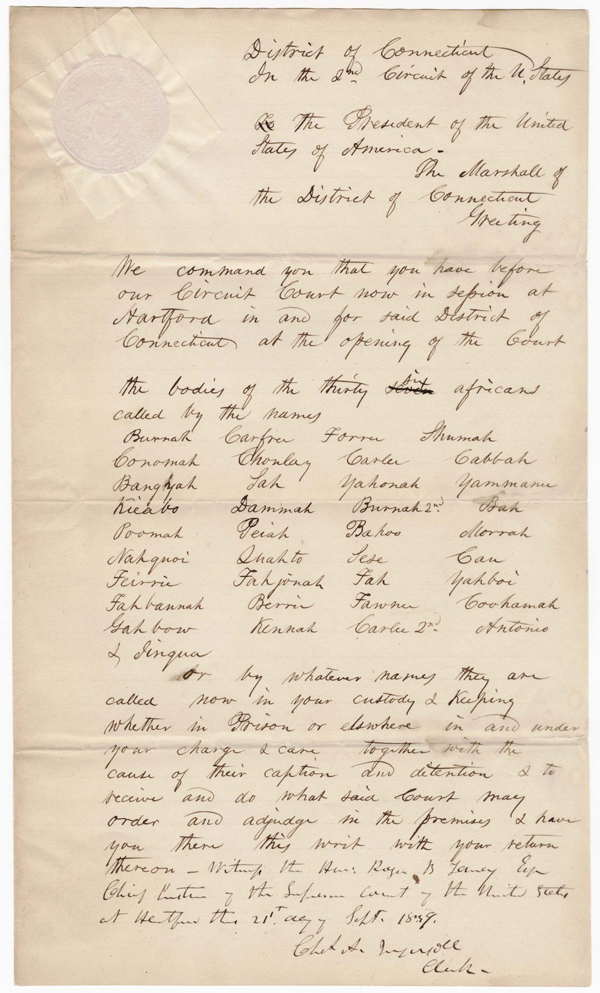

Montes and Ruiz actually steered the ship north; and on August 24, 1839, the Amistad was seized off Long Island, NY, by the U.S. brig Washington. The schooner, its cargo, and all on board were taken to New London, CT. The plantation owners were freed and the Africans were imprisoned on charges of murder.

Although the murder charges were dismissed, the Africans continued to be held in confinement and the case went to trial in the Federal District Court in Connecticut. The plantation owners, government of Spain, and captain of the Washington each claimed rights to the Africans or compensation.

President Van Buren was in favor of extraditing the Africans to Cuba. However, abolitionists in the North opposed extradition and raised money to defend the Africans. Had it not been for the actions of abolitionists in the United States, the issues related to the Amistad might have ended quietly in an admiralty court. But they used the incident as a way to expose the evils of slavery and generate significant opposition to the practice.

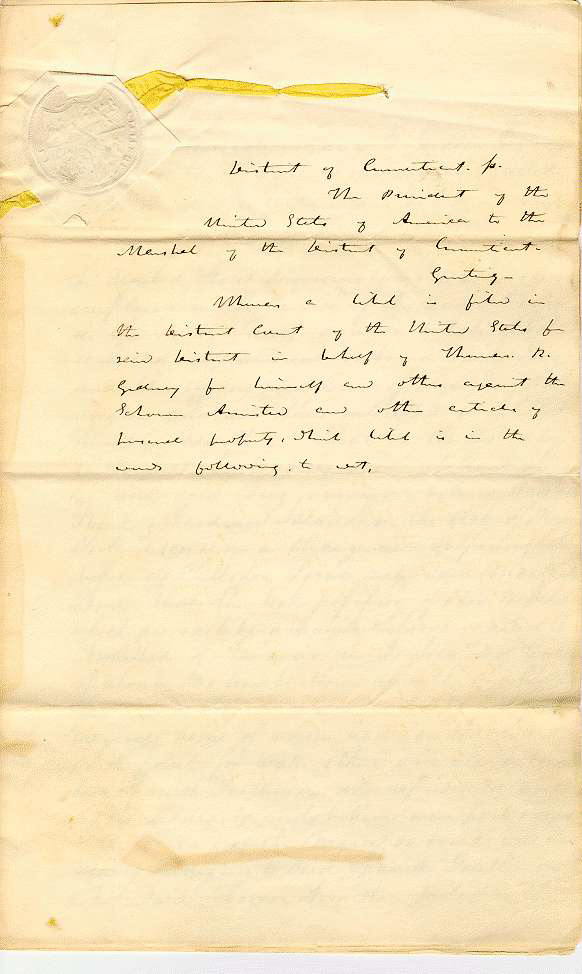

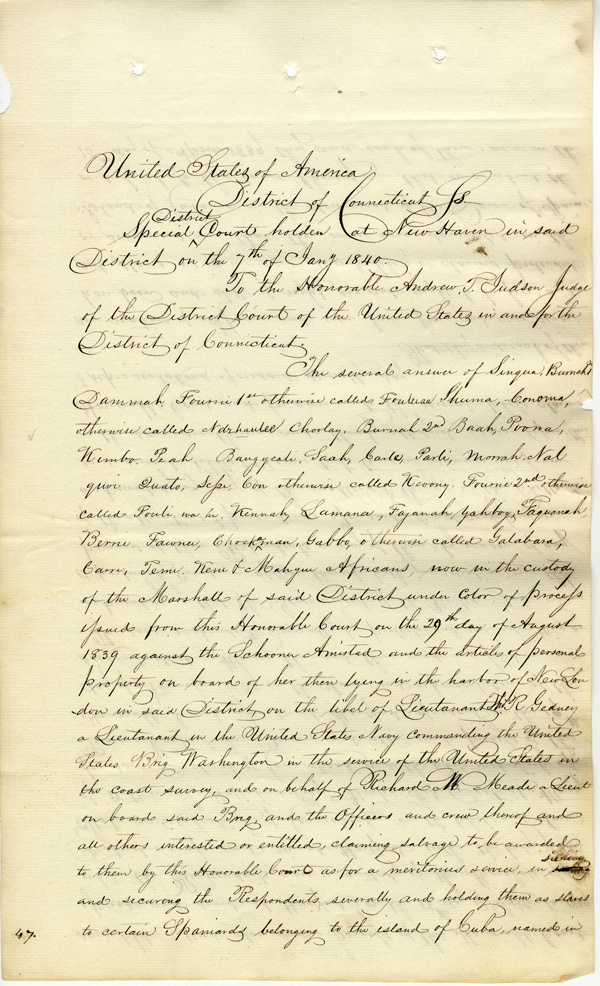

The brig Washington that seized the Amistad was commanded by Lt. Thomas R. Gedney. In maritime law, compensation is allowed to persons whose assistance saves a ship or its cargo from impending loss. Lt. Gedney claimed that it was with great difficulty and danger that he and his crew were able to recapture the Amistad from the Africans. They claimed that, had they not seized the vessel, it would have been a total loss to its "rightful" owners. Gedney and his crew believed they were entitled to salvage rights (or the full $65,000). At that time in U.S. history, even individuals acting in their official capacity as officials of the government were entitled to salvage rights.

In a libel, or written statement, in admiralty court, Gedney described the encounter with the Amistad. Because he sought salvage of the schooner and its cargo, he was very detailed in his account and itemized all of its cargo, estimating its value at $40,000 and the value of the Africans as slaves at $25,000. He relayed that the Africans could speak only native African tongues and that one of the two Spanish plantation owners, Jose Ruiz, spoke English. Gedney included in his statement the account of the mutiny as told by Ruiz.

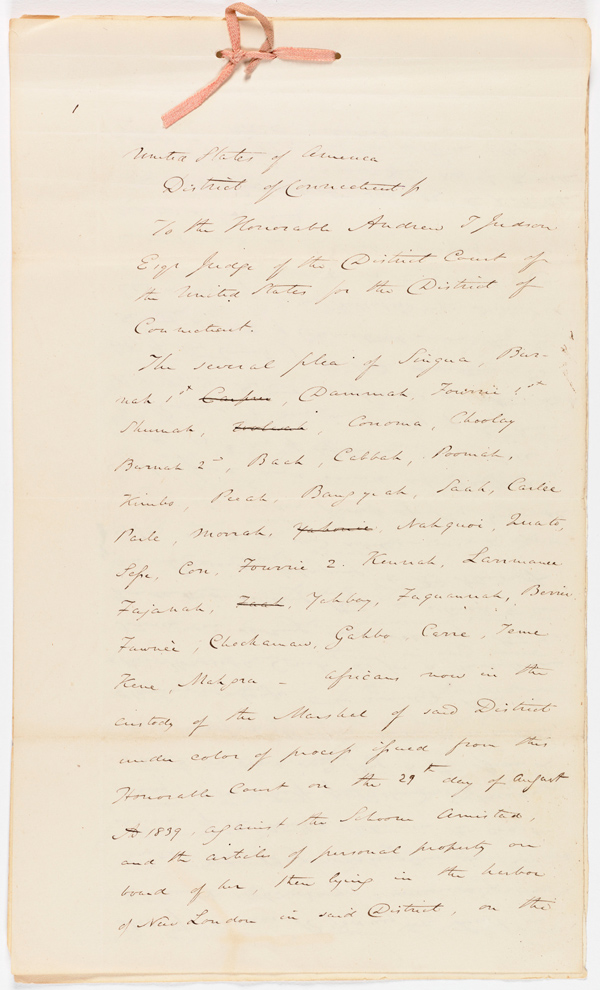

Abolitionists hired Roger S. Baldwin, a lawyer from New Haven, and two New York attorneys, Seth Staples and Theodore Sedgewick, to serve as proctors, or legal representatives, for the Africans.

The proctors submitted to the district court an answer to the libels of Lt. Gedney, Pedro Montes, and Jose Ruiz. It conveys the position of the Africans: "...each of them are natives of Africa and were born free, and ever since have been and still of right are and ought to be free and not slaves..." It states that they were not a part of a Spanish domestic slave trade and instead had been forcibly kidnapped from the African coast. And further that, while suffering “great cruelty and oppression” on board the Amistad, they were “incited by the love of liberty natural to all men” to take possession of the ship by force and seek asylum somewhere.

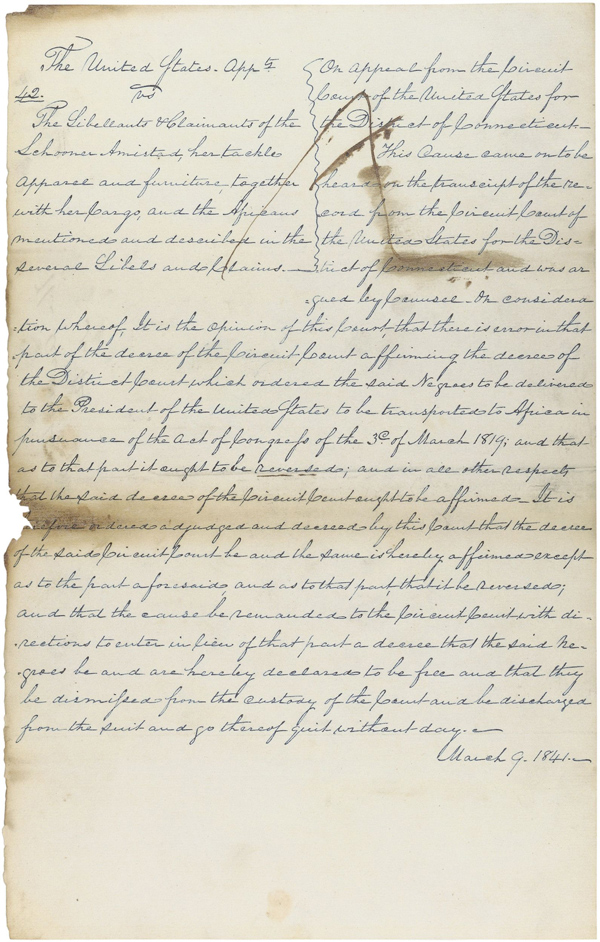

The district court ruled that the case fell within Federal jurisdiction and that the claims to the Africans as property were not legitimate because they were illegally held as slaves. The U.S. District Attorney filed an appeal to the Supreme Court.

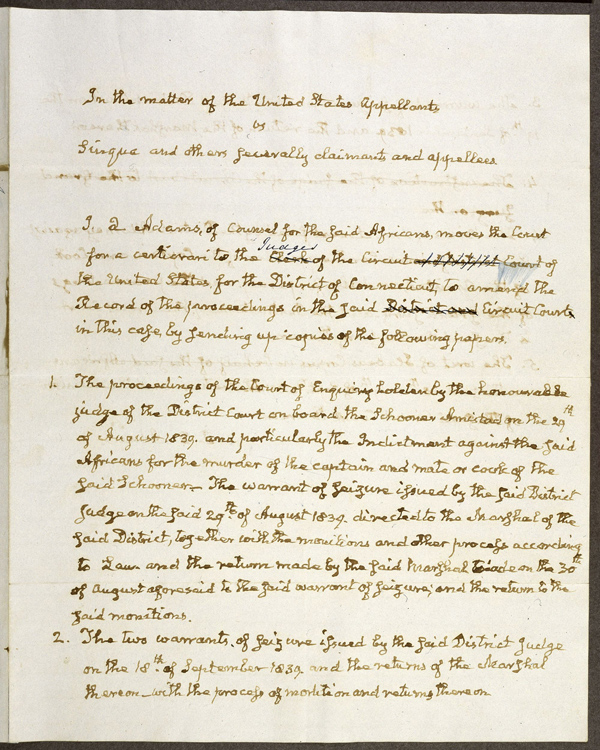

In the trial before the Supreme Court, the Africans were represented by former U.S. President, and descendant of American revolutionaries, John Quincy Adams. Preparing for his appearance before the Court, Adams requested papers from the lower courts one month before the proceedings opened. For 8 ½ hours, the 73-year-old Adams passionately and eloquently defended the Africans' right to freedom on both legal and moral grounds, referring to treaties prohibiting the slave trade and to the Declaration of Independence.

The Supreme Court decided in favor of the Africans, stating that they were free individuals. Kidnapped and transported illegally, they had never been slaves. Senior Justice Joseph Story wrote and read the decision: "...it was the ultimate right of all human beings in extreme cases to resist oppression, and to apply force against ruinous injustice." The opinion asserted the Africans' right to resist "unlawful" slavery.

The Court ordered the immediate release of the Amistad Africans. Thirty five of the survivors were returned to their homeland (the others died at sea or in prison while awaiting trial).

Materials created by the National Archives and Records Administration are in the public domain.

Materials created by the National Archives and Records Administration are in the public domain.

Materials created by the National Archives and Records Administration are in the public domain.

Materials created by the National Archives and Records Administration are in the public domain.