A History of the National Archives Building, Washington, DC

The National Archives Building is known for the history it holds, including the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. But the history of the National Archives Building itself is just as representative of democracy as the founding documents it holds. Learn more about the National Archives Building on our special topics page.

Short History of the National Archives Building

Planning Stages

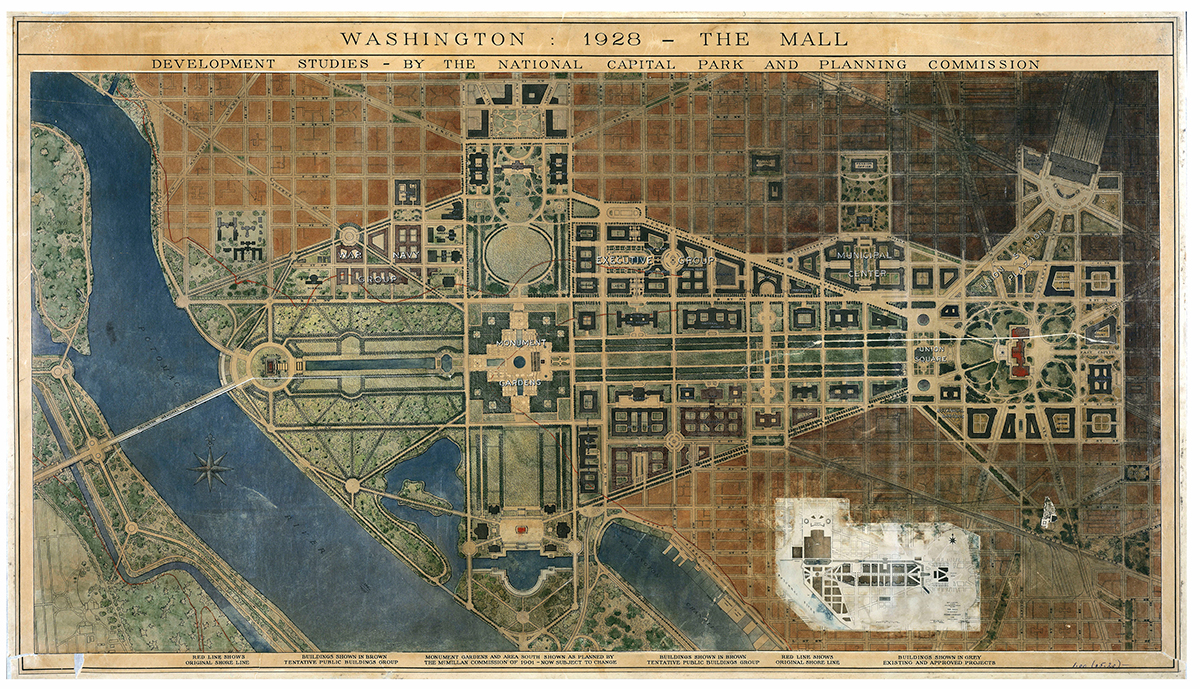

On May 25, 1926, Congress passed the Public Buildings Act authorizing a massive public buildings construction project, part of which was to provide office space for the growing federal agencies in the nation's capital. This program led to the design and construction of buildings within the Federal Triangle area of downtown Washington, DC, a then run-down area along Pennsylvania Avenue, NW.

Congress appointed the Department of the Treasury to carry out the plan. Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon assembled a group of the leading architects to design the federal buildings.

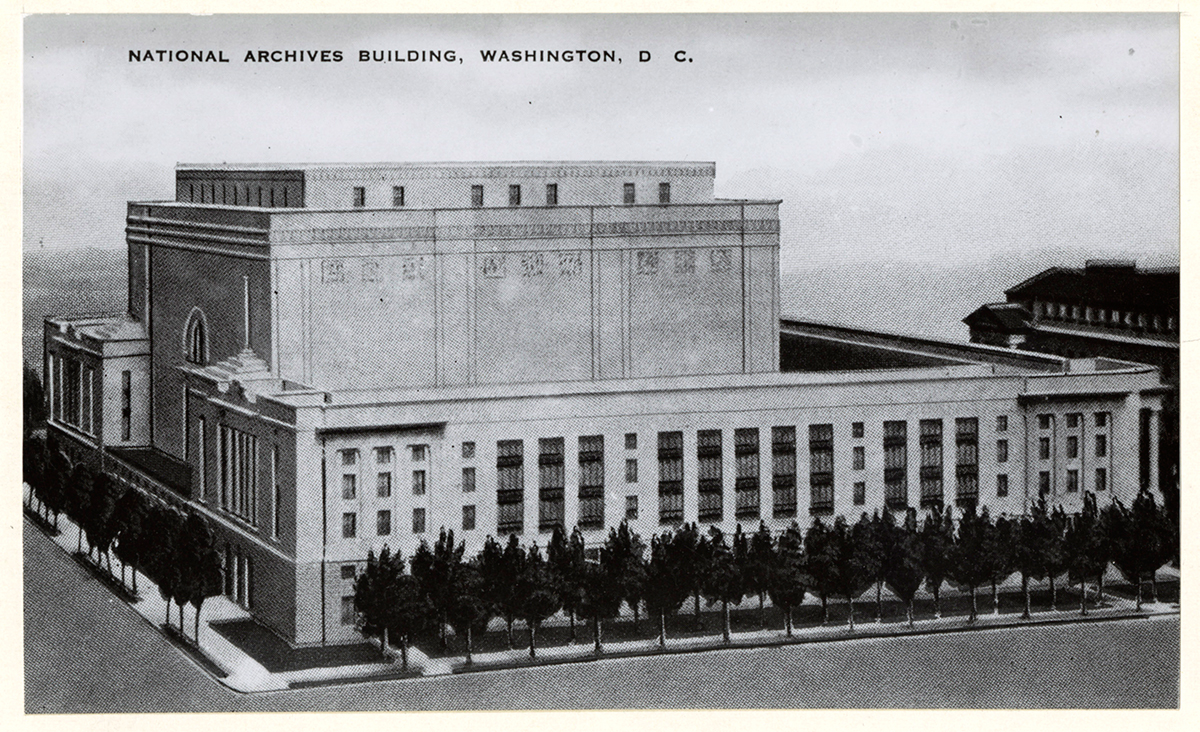

Mellon wanted the buildings to share certain design elements—limestone facades, red tiled roofs, and classical colonnades. He also wanted the buildings to be neoclassical in design following the architecture style of many federal government buildings that existed at that time.

The Commission on Fine Arts and the Public Building Commission had final approval on all plans. Immediately after Congress passed the legislation, the Public Buildings Commission announced its top priority was the construction of an Archives building along Pennsylvania Avenue, NW. Because of delays in site selection, land acquisition and design, the project was stalled a number of years.

The Archives building proved more difficult to design than the other federal buildings in the project because it was more than an office space for workers; it would store the most valuable records of the government. Architects on the project created a number of unsuccessful design plans of the Archives building.

The National Archives site also moved twice before the final location was chosen. The 1926 Public Building Commission plan placed the Archives between 12th and 13th Streets and B Street (now Constitution Avenue) and C Street NW. By 1927, the Archives site had moved to 9th and 10th Streets and B Street and Pennsylvania Avenue NW. Several plans from that era show the Archives on this site.

In 1930 Mellon selected New York Architect John Russell Pope to design the National Archives Building. Pope suggested moving the building to the land the Justice Department was slated to occupy—the block bounded by 7th and 9th Streets and B Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, NW—the current site of the National Archives Building. This was symbolic in that the building would be halfway between the White House and Capitol, and the new Archives would hold records from those institutions. The Justice Department building was then moved to its current location between 9th and 10th Streets, NW.

Construction

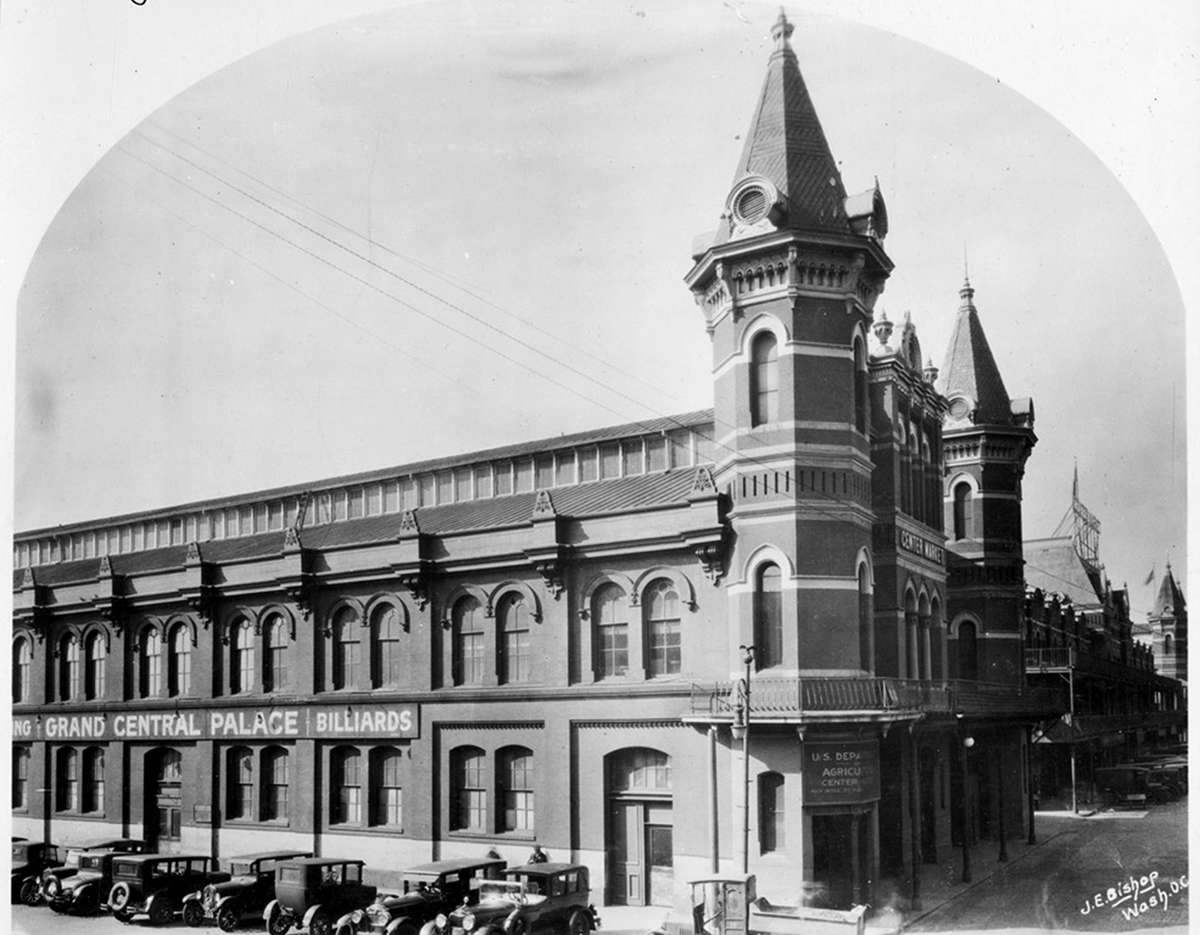

Since 1801 farmers markets had occupied the grounds where the new Archives was to be built. In 1931 the building that housed the Center Market, which had been erected in 1871 and held approximately 700 vendors, was demolished.

During the summer of 1931, the Commission on Fine Arts and the Public Building Commission approved Pope's plans. Pope's design included both the practical and symbolic aspects of housing the nation's records. He proposed a monumental structure with highly decorative architectural features, giant Corinthian columns, 40-foot bronze doors, and inscriptions representing the building's historical importance. Pope continued to fine-tune his drawings and specifications for the next year.

While plans for the building were not finalized, they were far enough along to start excavation.

The ground-breaking on Saturday, September 5, 1931, took place on the block embraced by Pennsylvania Avenue to the north and B Street (which would later become Constitution Avenue) to the south, with 9th and 7th street on either side.

At the ceremony, which was open to members of all government departments as well as the general public, Assistant Secretary of the Treasury Ferry K. Heath turned a spadeful of earth to mark the occasion.

In addition, Heath also gave a speech reminding those gathered of how momentous an occasion it was to see ground broken for the United States’ new federal archives.

One of the first issues builders confronted was how to protect the foundation from possible flooding from the Old Tiber Creek bed, which runs under the National Archives Building. Contractors drove 8,575 piles into the unstable soil before constructing a huge concrete bowl as a foundation.

On February 20, 1933, departing President Herbert Hoover laid the cornerstone of the building in a ceremony. Hoover dedicated it in the name of the people of the United States and proclaimed, "This temple of our history will appropriately be one of the most beautiful buildings in America, an expression of the American soul. It will be one of the most durable, an expression of the American character."

In the cornerstone, Hoover placed several items, including a copy of the Declaration of Independence, a copy of the Constitution, an American flag, and copies of the Washington daily newspapers.

Not only was the Archives building the most ornate structure on the Federal Triangle, but it also called for installation of specialized air-handling systems and filters, reinforced flooring, and thousands of feet of shelving to meet the building's archival storage requirements. The building's exterior took more than four years to finish and required an array of workers ranging from sculptors and model makers to air-conditioning contractors and structural-steel workers.

On June 19, 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed legislation creating the National Archives as an independent agency, and on November 5, 1935, the first National Archives staff members moved into the uncompleted building. Most of the exterior work was complete, but stack areas had no shelving for incoming records.

Work also continued on the exhibition hall and other public spaces. Most significantly, earlier estimates about the need for future stack space proved insufficient. Almost as soon as Pope's original design was complete, a project to fill the Archives' interior courtyard began, doubling storage space from 374,000 square feet to more than 757,000 square feet.

In 1934 American artist Barry Faulkner was commissioned to paint two murals for exhibition hall—a space now known as the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom. Originally painted in New York City, the murals were installed in 1936.

The mural on the northwest wall depicts Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston reporting the Declaration of Independence to John Hancock.

The mural on the northeast wall shows James Madison submitting the Constitution to George Washington.

In 1937 the National Archives Building was complete. It has 72 Corinthian columns that are each 53 feet high, 5 feet 8 inches in diameter, and weigh 95 tons.

The two bronze doors that guard the Constitution Avenue entrance each weigh 6½ tons and measure 38 feet 7 inches high, nearly 10 feet wide, and 11 inches thick.

Measuring 118 feet wide and 18 feet high at their peaks, the pediments on the north and south sides of the National Archives Building are the largest in Washington, DC.

On pedestals near the entrances are four large allegorical sculptures. At the Pennsylvania Avenue entrance, the sculptures represent the Future and the Past; on the Constitution Avenue side, the sculptures represent Heritage and Guardianship.

Additional sculptures in the pediments depict figures representing destiny, history, guardianship, and inspiration.

The medallions surrounding the building depict the Great Seal of the United States and emblems of the House of Representatives, Senate, and departments of government that existed at that time—symbols of the records that are housed in the building.

Three inscriptions encircle the building. The west side reads:

The glory and romance of our history are here preserved in the chronicles of those who conceived and builded [sic] the structure of our nation.

The east side reads:

This building holds in trust the records of our national life and symbolizes our faith in the permanency of our national institutions.

The south side reads:

The ties that bind the lives of our people in one indissoluble union are perpetuated in the archives of our government and to their custody this building is dedicated.

The “Charters of Freedom”

When the building was completed in 1937, the Rotunda did not hold the documents now nearly synonymous with the National Archives: the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. Pope had designed the National Archives Rotunda as a shrine for these documents, but both documents were still housed at the Library of Congress.

On December 13, 1952, after years of negotiation between the Archivist of the United States and the Librarian of Congress, the two documents were transferred to the National Archives. Together with the Bill of Rights, which had been transferred to the Archives in 1938, the National Archives refers to these three documents collectively as the “Charters of Freedom.”

The transfer began with the commanding General of the Air Force Headquarters Command formally receiving the Declaration and Constitution at the Library of Congress at 11 a.m. After being paraded down Pennsylvania and Constitution Avenues accompanied by members from all branches of the military, at 11:35 am, the General and 12 policemen carried the documents up the Constitution Avenue stairs into the Rotunda and formally delivered them into the custody of the Archivist of the United States.

On Monday morning, December 15, 1952—Bill of Rights Day—Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson presided over the formal enshrining ceremony attended by President Harry Truman and other dignitaries. That year the National Bureau of Standards placed the documents into hermetically sealed encasements filled with inert helium gas, where they stayed for nearly 50 years.

In the early 1970s, in preparation for the 200th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, the National Archives undertook its first major renovation since the 1930s.

Workers cleaned the outside façade, sculptures and artwork. Inside, workers updated the air-conditioning system; and installed new lighting, smoke detectors and sprinklers. The Faulkner murals, and the Rotunda ceiling and walls, marble and other stonework were also cleaned.

The 21st Century

Beginning when the “Charters of Freedom” were installed in 1952, National Archives conservators regularly visually inspected the encased documents.

In July 2001 the National Archives removed the Constitution, Declaration of Independence, and Bill of Rights from display in the Rotunda so conservators could more closely analyze their condition. New display cases were being made as part of a massive renovation of the National Archives Building, which took place between 2001 and 2005.

The Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights were debuted on September 18, 2003, in new airtight cases. The new cases allowed four pages of the Constitution to be displayed and made the documents more accessible to visitors with disabilities. The main visitor entrance on Constitution Avenue was moved from the large bronze doors on top of the steps to a ground-level entrance. The two Faulkner murals, which had deteriorated significantly, were also restored.

Other aspects of the renovation included: an upgrade of the building systems; improved security and storage conditions; compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act; and the creation of new exhibit space, a learning center, a gift shop, and a cafeteria. The renovation also included closing the original fifth-floor theater and constructing the new 290-seat William G. McGowan Theater on the lower level.

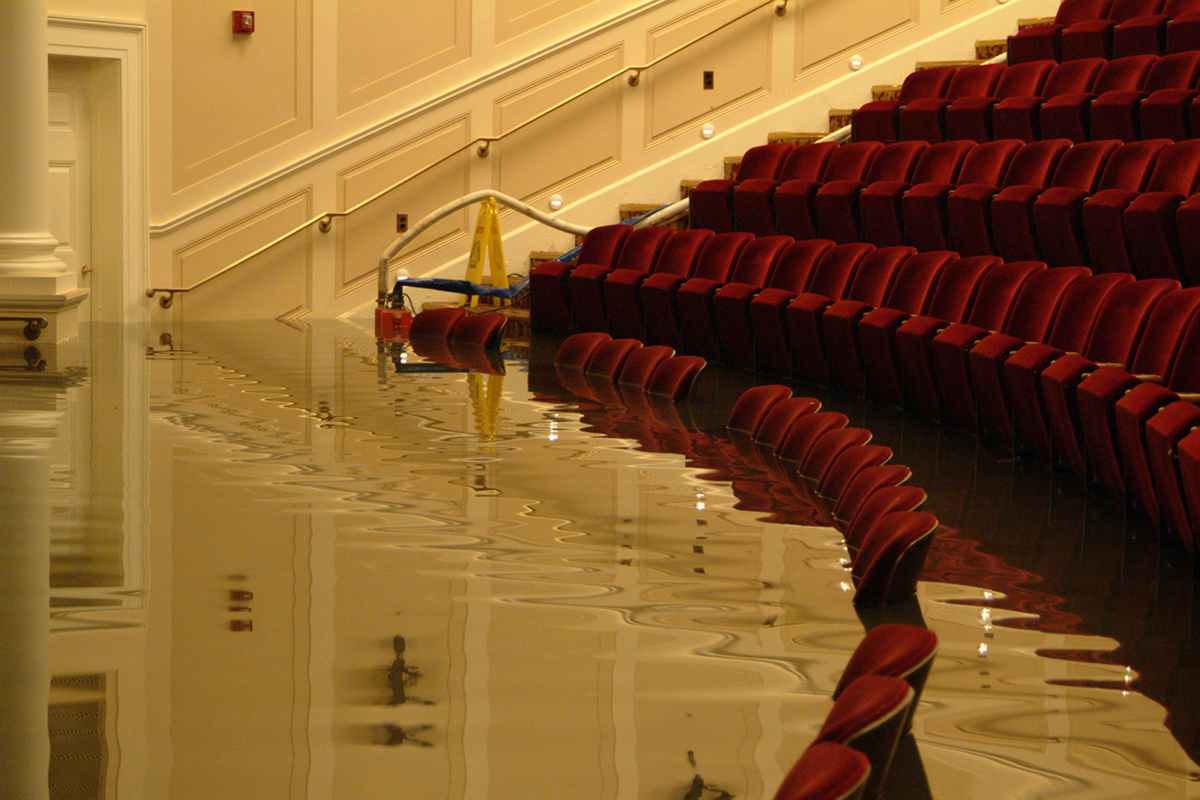

Beginning the night of June 25, 2006, record-breaking rainfall in the Washington, DC, area caused flooding in several buildings in the Federal Triangle, including the National Archives. The water flooded the National Archives Building's transformer vaults and sub-basement, causing power loss and significant damage. No original records were damaged by the flood, but the building was closed for nearly three weeks while crews made repairs. The McGowan Theater remained closed until October 2006.

On December 13, 2023, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland designated the National Archives Building as a National Historic Landmark.

For more information on this history of Archives II, visit the History of the National Archives at College Park.